In the annals of advertising history there exists a famous old print ad, usually the domain of long defunct journals like People, Australasian Post and other pot boilers. The headline read, “They laughed when I stepped up to the piano…” followed by the sub heading, “But when I started to play…!” It extolled the virtues of mail-order piano lessons, but it reminds me of the reaction when Yamaha introduced its first serious racer-for-the boys, the TD1. Yes, some people laughed. But not for long.

At this time, 1962, the 250cc racing class was in a world-wide state of flux. The works machines from the Italian MV, Benelli and Mondial factories, plus the German NSU had gathered the world championship titles in the 50s, but few of these ever found their way into private hands. It was the same in the 60s, when Honda took over to wrestle the mantle from MV Agusta in the Lightweight classes.

But at privateer level, and at national-based meetings worldwide, the ranks of the Lightweight Class (up to 250cc) were filled with an assortment of odd bods ranging from pre and post war British OHV singles, home made OHC conversions to the same, a few NSU singles, British two strokes and a handful of converted ex-road bikes from Honda, and Yamaha. In the case of the latter, the YDS1 was a good basis for a play racer, and even resembled the factory RD-48 in many ways.

Companies like Adler, MZ and years earlier, DKW, had shown that the two stroke design had legs – if only the traditional bugbears could be conquered. Metal technology, lubricants, and critically, ignition systems were the ’strokers <i>bete noir<i>. All three improved dramatically in the next 20 years, but it was not until the arrival of reliable transistorised ignition in the late 60s that two-stroke reliability increased to the point that other technology advances could be exploited.

Of the emerging Japanese factories, Suzuki and Yamaha were making huge strides with their road-going models, but while Suzuki chased the tiny end with 50s and 125s, Yamaha concentrated on developing their YDS1 250 twin. This engine had strong links to the German Adler, including several of its inherent faults. The yawning American market was discovering 250s in a big way, to the point that the Yamaha factory sent Fumio Ito to California in 1958 to contest the grandly-titled Catalina Grand Prix with a YD-B.

Encouraged by the reaction to Ito’s sixth place, Yamaha produced the YDS1 in 1959, and soon after began offering racing kits for sale. The road-race kit (there was also a ‘scrambles’ package) effectively replaced the entire top half of the engine, as well as the Hitachi ignition system, with bigger carburettors and expansion chamber exhausts. There was also a huge six gallon (22.7L) fuel tank and a racing seat, rear-set footrest, gear linkage and brake lever. The tuned YDS1 poked out around 25 horsepower at 9000rpm, but reliability wasn’t a key point. The iron-lined barrels and aluminium pistons had an unhappy relationship, with seizures commonplace. Yamaha eventually solved, or at least ameliorated the seizure problem by increasing the silicon content of the pistons to run in all-aluminium cylinders with anodised walls.

American Sonny Angel (who was one of the first Yamaha dealers in the US) took a pair of race-kitted YDS1Rs loaned to him by Yamaha to the 1960 Isle of Man TT. The TT was part of a racing tour which began at Brands Hatch, where the bike seized repeatedly.

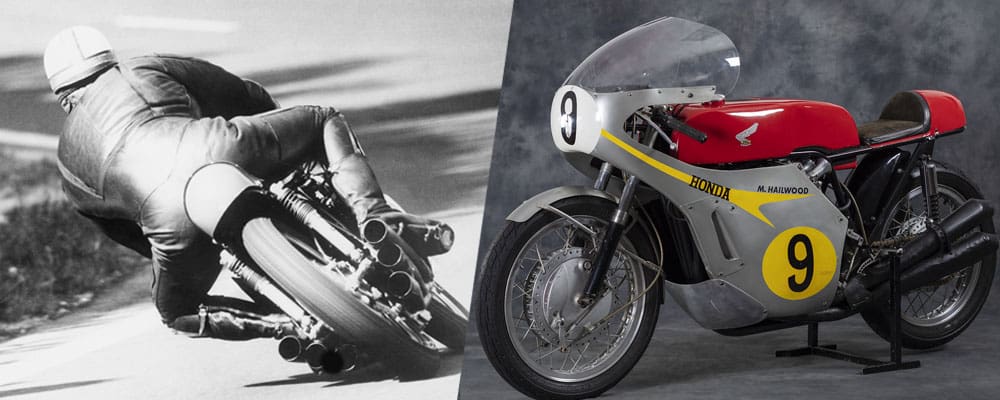

Next he contested the international meeting at Silverstone, where the bike appeared with a complete Manx Norton front end. Although he finished the race, he was lapped three times by Mike Hailwood’s Ducati twin. By the time he arrived at the Isle of Man he had run out of pistons and modified a set of Hepolite scooter pistons which failed to see out the practice sessions.

Nevertheless, Yamaha pressed on with customer tackle, offering the YDS1R in very limited numbers from around 1961. It is believed nine of these came to Australia, sold by Milledge Bros in Melbourne and Tom Byrne in Sydney.

Yamaha’s next step was the YDS2, introduced in March, 1962. Again, a race kit was offered, comprising special cylinders, pistons, expansion chamber exhausts and racing carburettors, raising power by about five horsepower, but on the track, the Yamaha’s roadster heritage was still a disadvantage when matched against the current tackle, which included two-stroke singles from Bultaco and the four stroke Aermacchi. The Brits were also in on the concept of 250 two-stroke singles, with Greeves, Cotton, DMW and various other brands all experimenting with their own concepts.

Track attack

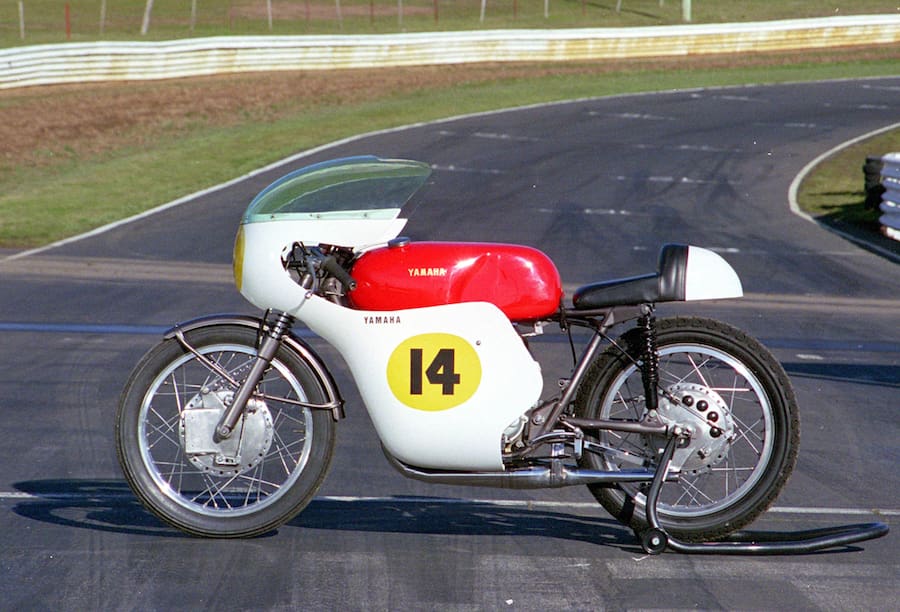

A dedicated racer was needed, and in late 1962, the first of the TD1 series was displayed at the Tokyo Motorcycle Show. Although still based on the YDS2 lineage, the TD1 incorporated, for the first time, a frame expressly made for competition. The components of the front end, including both top and bottom fork yokes, hydraulic fork legs, axle and front brake were also specially-made items, but despite the attention to detail, the handling was significantly behind European standards.

The swingarm was basically identical to the RD-48 and the rear shocks were unique to the new model. While visually similar to the YDS2, the frame was made from lighter gauge material. One curious touch was a tachometer with no numbers on the face; instead were the letters A,B,C,D,E, F and G. Perhaps this is the origin of the phrase, “Rev it to F!”

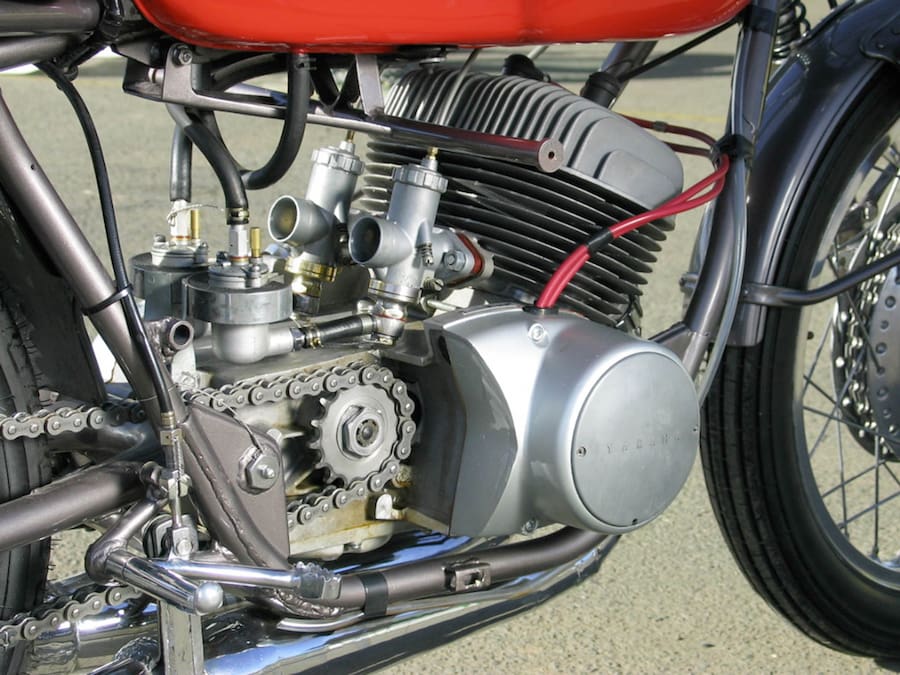

Horizontally split crankcases housed the five-speed transmission, with a 180-degree crankshaft running in four ball races and a labyrinth seal separating the two crankcase chambers. The barrels contained four ports with internal cylinder dimensions of 56mm bore and 50mm stroke, fed by a pair of 27mm Amal-replica Mikunis with remote bowls.

The engine too had come under intense scrutiny by the factory boffins, but in one respect was doomed to ignominy. The YDS2 (nee Adler) design had the clutch mounted on the crankshaft, running at engine speed. The shaft itself was of only 20mm diameter, and a missed gear or even an overly-energetic getaway could snap the shaft, sending the clutch flying through the outer casing. This design not only led to repeated crankshaft failures, but severely restricted the choice of gear ratios. On the TD1, internal ratios were the same as the YDS2 roadbike, with the exception of fourth gear – meaning that first gear was useless for anything but starts. Alloy cylinders with Nikasil-plated bores and an improved alloy mix for pistons improved reliability slightly over the seizure-prone race-kitted YDS1s. Yamaha tried chrome-plated bores for the subsequent TD-1A and TD-1B, but reverted to Nikasil for the TD-1C.

A small number of TD1 models was produced – estimates vary from 12 to 60 – with three each going to the UK and Australia, five or six to USA, and the rest distributed around the Far east and Japan. Reportedly, and for whatever reason, all these were supplied with lights. But the story really began in 1963 with the introduction of the TD-1A, a much more serious attempt at providing the privateer with competitive tackle. People were no longer laughing; this was a genuine challenger. The new racer wasn’t a bad looker, with a fairly raunchy (for the era) shade of blood-orange on the tank (Yamaha’s official racing colours of the time were dark orange and white), a silver-grey frame and white fairing. A handful was made available to key overseas markets- the majority going to USA. The first-completed example of the production run, after testing at Suzuka, went to the United Kingdom, where it miraculously survives to this day – the only known surviving example of the three exported to Britain. Of the estimated production run of 60, three are extant in USA, and three are known to exist in Australia. All of these were imported by Victorian Yamaha distributors Milledge Brothers in November 1963. Two were retained for their supported riders Allan Osborne and Ken Rumble, while the other was sold to Tasmanian ‘Ike’ Chenhall (see sidebar). The price was £495 ($990); slightly more than the final examples of the Manx Norton of the same year.

In Australia, we had already seen the race-kitted YDS1R and YDS2s getting among the results, particularly in Victoria where the energetic distributors were keen to see the fledgling Yamaha agency’s products represented on the track. Mick Dillon, Rumble and Osborne all punted the converted roadsters to various degrees of success, with Rumble scoring Yamaha’s first national title when he won the 1961 Australian 250 Short Circuit (dirt track) Championship at Campbellfield, Victoria.

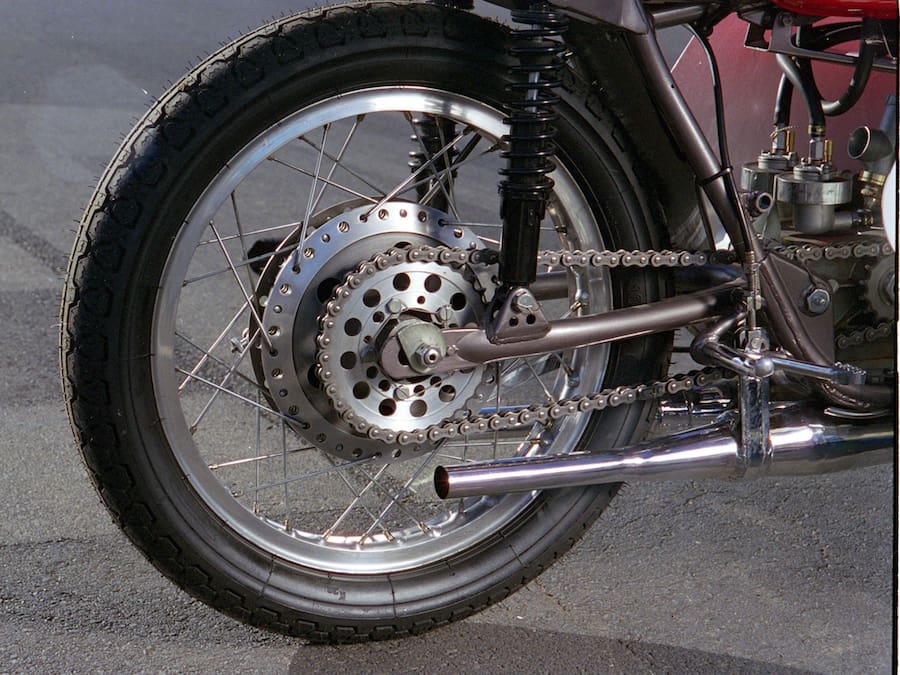

The TD1A was considerably beefed up, with extra gusseting around the steering head and box section mounts for the swinging arm. Mods to the engine brought power up to 35hp, which was certainly competitive, but gave the crankshaft-mounted clutch an even harder time. The clutch was probably the most significant in a considerable list of flaws that dogged Yamaha 250 racers right up until the introduction of the ground-breaking TD1-C in 1967, when the clutch was finally moved to the gearbox output shaft, where it belonged. At the root of the trouble was the jumble of cogs inside the gearbox, the ultra-low first gear separated from second by a yawning abyss that made tight circuits a challenge. The engine’s power characteristics were also pretty testing, especially compared to their single-cylinder Spanish rivals of the day. Usable power appeared at 7000rpm and departed rapidly at 9000. Although it was made from better-quality, thinner-walled tubing than the YDS2 roadbike’s frame, the racing unit was still heavy and flexy. One of the culprits was the top steering crown, made of pressed-steel, and this item was replaced with a cast alloy component on subsequent models. The A-model frame was also prone to cracking, especially through the front engine mounts, which were strengthened on the ‘B’. Several TD1 punters opted to change the chassis completely. One successful hybrid in England, the Doncaster Yamaha ridden by Billie Nelson, slotted a TD1B engine into an ex-works Ducati frame and achieved reasonable success. Even more successful was Rod Gould’s hybrid, with a TD1A engine fitted to a Bultaco TSS chassis.

On the YDS3-based TD1B, released in 1965, the crank diameter was increased to 25mm, which went some way to improving reliability. In fact, the TD-1B shared virtually no engine components with the ‘A’. The TD1B again sported new cylinders, pistons, heads, ignition system, and carbs, adding up to a 4hp increase, which was due in no small part to revised expansion chambers. Despite the extra power however, handling was still not up to scratch, leading to several top privateers plucking the Yamaha powerplant and placing it in numerous chassis, mainly of European origin.

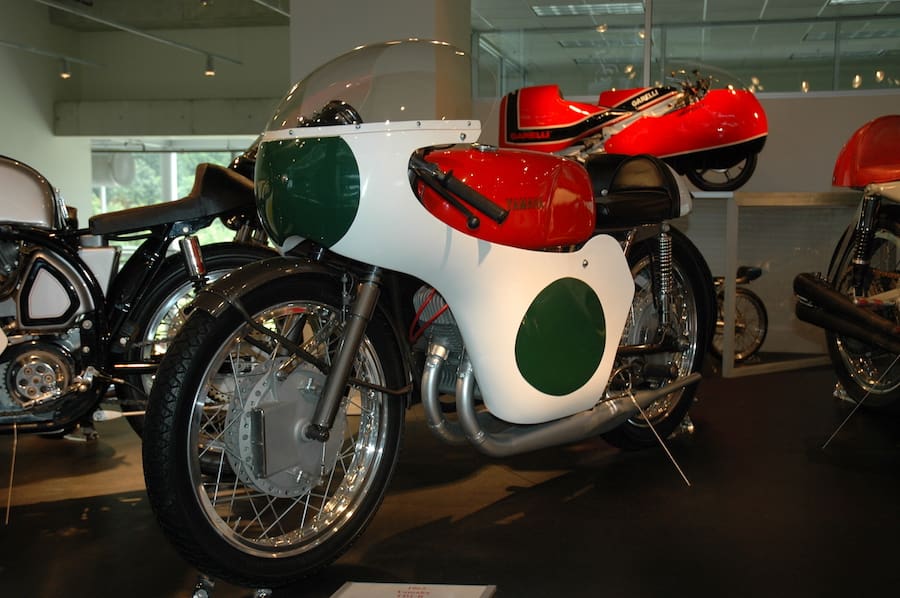

In early 1967, Yamaha released the YDS5, and this led directly to the TD1C, a significant improvement over its predecessors, although the frame was largely unaltered. The new designed used an American-developed five-port cylinder which gave much improved gas flow, and most importantly, the primary gear shaft-mounted clutch, which in turn permitted a complete redesign of the gearbox. The TD1C found its way to Australia in greater numbers than the earlier models, and quickly became the preferred kit for the 250cc class, as well as being quite competitive in the 350cc or Junior class. Visually, the ‘C’ differed little from the earlier bikes, using the large jelly bean shaped white fuel tank that first appeared on the later model TD1Bs that replaced the red RD-48 ‘bread loaf’ style. In the hands of top liners like Ron Toombs, Peter Richards, Alan Osborne and Bryan Hindle, the ‘C’ dominated. But if the ‘C’ had a failing it was the adherence to points ignition. While the unreliability was no such a factor in the comparatively short Australasian races, it certainly was in Europe. Ross Hannan raced a TD1C in European international meetings and selected GPs in 1969. “The ignition was a huge problem,” he says. “I was in world championship points on at least two occasions when the ignition timing moved and it seized. But for its time it was great to ride.”

In the lineage that began with the TD1, the TD1-C was comparatively short-lived, as Yamaha had something far more advanced in the pipe line; the 250cc TD2 and 350cc TR2 – often referred to a “Daytona” Yamahas after the prototype raced by Canadian Mike Duff at the US classic in 1967. But that’s a separate story. In had taken Yamaha less than a decade to come from giggle-stock to category leader, and this was really just the beginning. The thin end of the wedge.

Words Peter Turner Photography Independent Observations