A bucket list is a great thing to have, and the contents of your bucket should never be watered down by reality. Nor should there ever be a limit on the size of your bucket.

I believe we motorcyclists are predisposed to liberal indulgence in this area, and I know I am. The best part about wandering unexpectedly into the life of a journo is that it has made my enormous bucket of unlikeliness suddenly appear to contain tantalisingly large portions of possibility, to which I must say yes.

One such example is having the opportunity not only to ride but to race one of the most iconic motorcycles of all time. In fact, the Yamaha TZ750 is the icon of an iconic era of racing.

This fearsome thoroughbred represents all that is great and slightly demented about motorcycle racing. It’s a living, blue-smoke-breathing relic of a time when it was still possible to purchase a piece of mechanical lunacy from your friendly Yamaha dealer and set off to join the circus – and maybe even conquer

the world.

The owner of this particular piece of rolling history knows more than most about this era of racing. Although, ironically, Barry Ditchburn spent a great deal of the TZ750 boom time wishing they weren’t so bloody good. ‘Ditch’ was a Kawasaki factory rider in the mid to late seventies, charged with the task of beating the TZs on an under-performing KR750.

Making up for those golden years spent fighting against the might of the TZ, Barry has now become a leading force in bringing the sight, sound and smell of big TZs back to the racetrack. He has even involved his son Craig in the cause. Together they have been instrumental in helping their sponsors, Consortium Racing, to recently start producing new crankcases, thus finally completing the holy trinity of reproduction parts required to construct brand new TZ750s.

There’s a very good reason why it has taken till now for new crankcases to become available – they are extremely hard to make correctly, and if they are made incorrectly, there is the distinct possibility that nothing else will work. The fact that the task has been mastered by a consortium of Australian manufacturing companies and engineers is certainly worth celebrating.

The rest of Ditchburn’s TZ is a mix of reproduction parts made overseas: nikasil-lined barrels from Italy, forged pistons from America, crankshafts from the UK, and a multitude of other parts made by Ditchburn and his son in their impressive American-barn-style workshop. This cathedral of creativity in the hilly outer-east suburbs of Melbourne is crammed with the means to make just about anything you can dream of.

The tank has been handmade by Barry using an English wheel, and the reproduction TZ750 frame is also his handiwork. One of the most impressive pieces of in-house engineering is the throttle assembly. Not only has the aluminium housing for the throttle been constructed in-house, but also the twistgrip and cables which operate the four original TZ750 Mikuni carburettors.

But that’s the deal when you are drawn to worship such rare and idiosyncratic machines as these; if you can’t buy it, or can’t afford it, you’d better be bloody good at making it.

I’m no stranger to the oddities and rituals of two-stroke engines. In fact, it was a fascination with making them go faster that led me through my home education to gain a self-determined B minus in motorcycle engineering, specialising in stink wheel tuning at the Adelaide campus of the University of Life. I started on home-tuned Lambrettas, then moved on to Yamaha YB100 and Honda H100 bucket racers, a Kawasaki 350 triple, a Yamaha powered Niko Bakker 125GP bike, a couple of Suzuki RGV 250s, and the final two-stroke in my catalogue of racing endeavours, the Harris-framed Yamaha YZR500, which I raced in the last seven 500cc grands prix of 1996.

So as you can see, my blood has long been pre-mixed with, and my nostrils predisposed to, sweet-smelling castor-based oils. And after 20 years, the fascination and passion is still there.

Riding the TZ750 for the second time made me remember an adage my old mate Tom Larsen used to recite, that ‘everyday’s a school day’. So right, and there are still many lessons to be learnt after 47 years at the University of Life, two-stroke faculty.

A handling problem that I couldn’t quite pin down at my first test ride in December, became glaringly obvious within a few laps at the subsequent test day in January. But it turned out to be a red herring – it wasn’t a handling issue at all. Carburation, that old black art and sacred ritual of two-stroke racing, was the cause of the TZs misdemeanours, and both the cause and effect were certainly new sensations for me.

My next nearest experience to the big TZ was the 20 years younger YZR500, and with its narrow twin crankshafts, modern carburettors, stiff aluminium twin-spar chassis, and ultra-firm suspension, on the rare occasions the carburation was out on the YZR500, it never reacted like the TZ750 does with its wide inline crankshaft and somewhat softer and twangier chassis. Even a slight richness in the fuel air mixture can upset the balance in the TZ engine enough to make it reverberate its indignance through the whole bike. And a major dose of too much fuel actually had the front wheel bouncing off the ground through Siberia at one stage. Exciting stuff, but nearly a very expensive lesson.

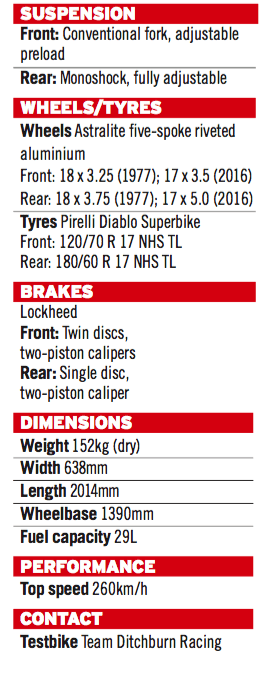

The reason for the carburation being out seemed to be the TZ’s new set of pipes. Barry had just created them, but hadn’t yet had a chance to perfect the jetting. Barry makes all his own exhausts too, and has burnt endless tins of elbow grease and gas in the quest for that perfect balance of power and rideability. The homemade bike dyno Craig knocked up in his spare time is a handy tool for bedding things in, and even for checking that the main jets are in the right range before heading to the track. But being a simple inertia dyno it lacks the ability to control load on the engine, which is necessary for finalising carburation settings.

Back at Phillip Island we were making progress with the jetting – and with it the handling. Eventually the leanest needles and needle jets were fitted, and still it wanted less fuel at engine speeds of 6000-8000rpm. But the good news was Barry’s new pipes were working well, giving more power up around the 11,500rpm limit, and there wasn’t a great deal to improve on the suspension or chassis once we’d nailed the jetting. An order was sent to the United States for leaner needles, and our only remaining problem was that we’d only know whether they did the job once we got to the Island Classic to go racing.

On our return to the workshop, Barry became suspicious that the carburation problem may actually have been caused by one of the float bowls flooding, so just to be sure, a brand new set of reproduction carbies were fitted. To my delight, these had the idle adjustment the originals lack, allowing me to dial out the long delay between starting to twist the throttle and getting the engine to chime in. This promised to be a big benefit for slower turns, helping me maintain momentum by getting back on the throttle smoother and earlier. Happy days.

My only other disagreement with the TZ was another odd one. Although I’m only 173cm, and shrinking daily, I struggled to fit my emaciated vessel into the Yammy’s cockpit. My feet were crammed up my arse further than anyone should ever know themselves, my knees pressed heavily against the rear edge of the fairing when in race tuck, and my helmet bashed the screen every time

I hung off through the turns.

Thankfully the Ditchburns are both 100 per cent racers, as well as being talented engineers – they understand that different riders need different things, even if it means modifying one of their prized possessions. By the time test ride number two came around, a new 50mm taller seat had been manufactured by Craig. Although, in typical Ditchburn style, he’d only made it himself after the job done by a professional automotive upholsterer failed to meet their high standards. The fairing and screen were then trimmed down to reduce rider interference, and all of a sudden it was a TZ750 tailored for yours truly, something which far exceeded even my wildest bucket list expectations.

Once the TZ was tweaked to fit my size and riding style it became a totally different tool, turning my riding approach from awkward idiot to track-attack mode. This transformation allowed me to really start appreciating the Yamaha’s strengths and character.

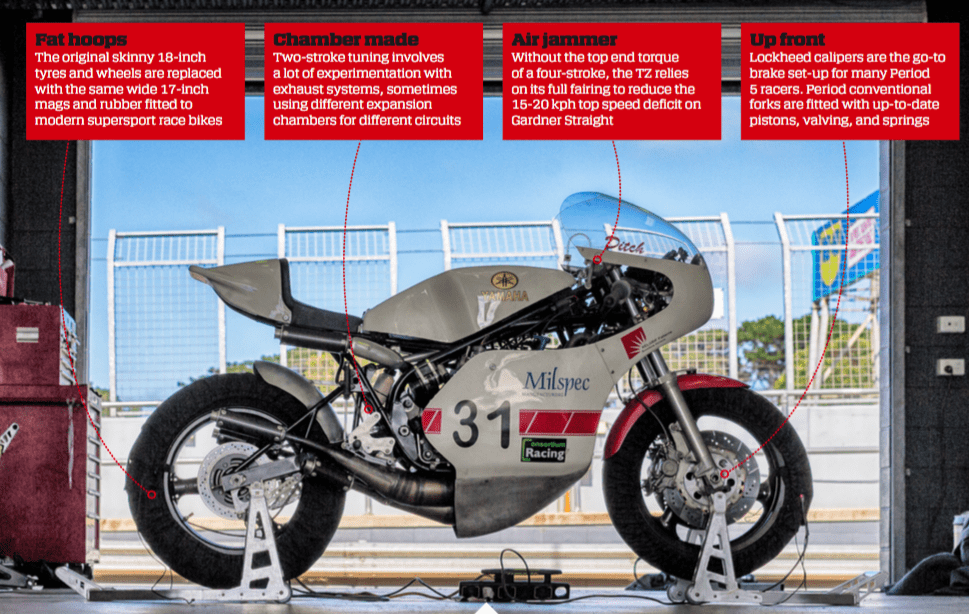

First and foremost, this is a relatively lightweight machine, as can be felt in its fleet-footed direction changes, and also in its braking performance. It’s under heavy braking that the TZ excels compared to the four-stroke machines of its era I’ve ridden. The TZ is limited to the same braking hardware as those bikes, but seems to be able to make more use of the stopping power available. This is probably down to overall weight and also its distribution, with the two-stroke keeping its mass located lower in the chassis. But it also has a lot to do with the ease of gear selection offered by the TZs close-ratio transmission. Firing rapidly down through the gears at the last possible moment is something the TZ handles well. In comparison, the four-strokes of the period require the rider to give a lot more time and thought when changing down through the gearbox.

Although some new-build TZ750s are being fitted with slipper clutches, Ditchburn doesn’t see a need for it, and I whole-heartedly agree. The engine braking from the multi-cylinder 750 is greater than is normal for a two-stroke, but still nowhere near as extreme as a high-compression four-stroke. I’d say it’s just right, and the non-slipper dry clutch is progressive enough to do all the necessary slipping the good old-fashioned way – manually.

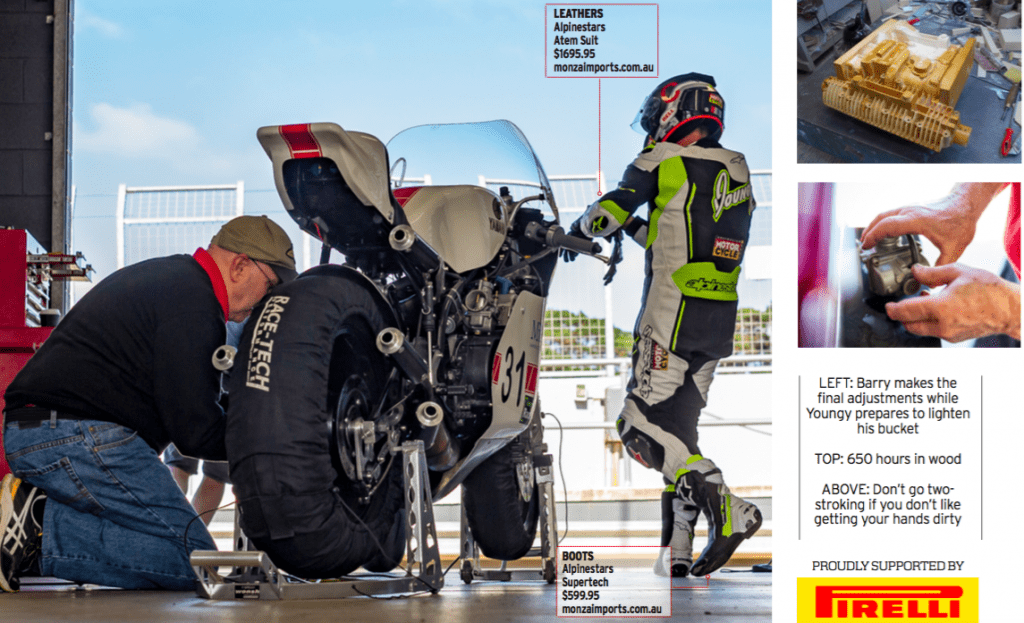

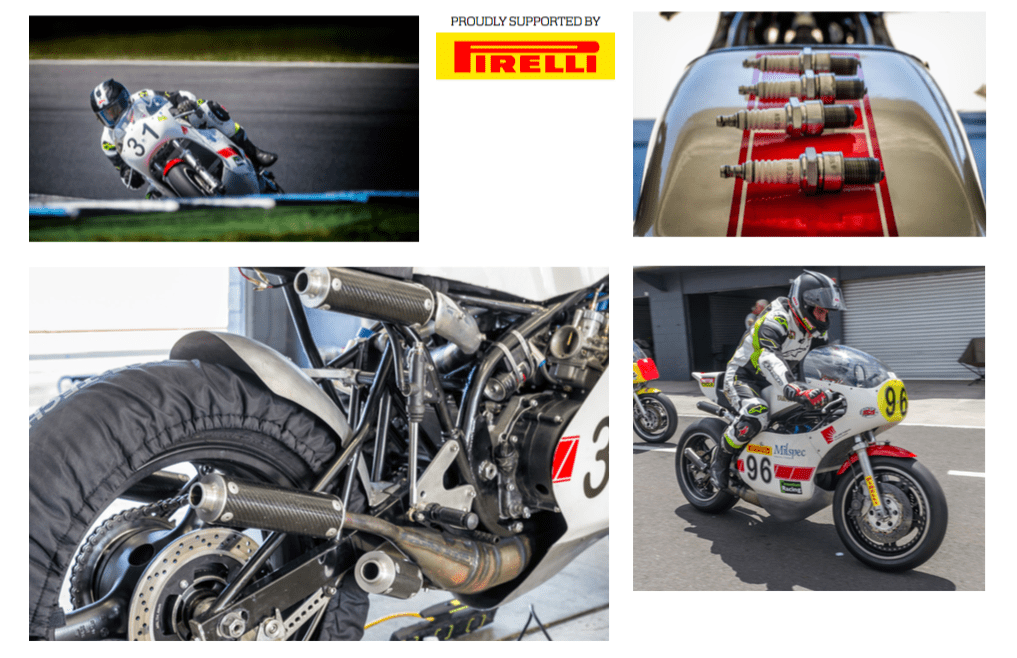

The suspension is handled by Öhlins internals in the period-conventional forks, with a Wilbers damper controlling the standard TZ-type cantilever swingarm. Over the two test days we stiffened both ends of the bike quite drastically, which I find is the best way to get the very non-period sized wheels and modern racing tyres – allowable under Period 5 historic rules – to work on these 40-year-old bikes. The amount of grip available with the Pirelli Diablo slicks we will be using at the International Island Classic would have blown the minds of TZ racers back in the seventies, and definitely requires the suspension tuning rulebook of those days to be thrown in the bin.

One surprise was that I never found the notoriously fearsome TZ750 engine to be all that scary. Sure it comes into its usable power band with a bang, but it is no less controllable than a four-stroke superbike.

By the time you are reading this, you may well be leaning on the fence at turn one, screaming “Come on Aussies!” at the AMCN International Island Classic. Just do me a favour and also shout “Come on the two-strokes!” Coz I’ll be needing all the revs I can get!

Collective intelligence

Consortium Racing is both the brainchild and a labour of love for historic racing enthusiast Gary Kerr. A long-time admirer of the Ditchburn dedication and workmanship, Kerr admits the company he formed to collectively manufacture brand new TZ750 crankcases was driven purely by his passion for a very worthy cause: to help Team Ditchburn keep these icons of road racing on the racetrack, where they belong.

Originally, Gary offered to help with the machining of a set of blank crankcases Barry had imported. A European TZ builder had set about becoming the first in the world to reproduce TZ750 crankcases, but after having the castings made, they couldn’t find anyone willing to take on the machining side of the job.

Kerr’s involvement in the manufacturing sector led to the task being completed by Albury-based company Milspec Manufacturing. These European castings proved to be so inconsistent in shape that Milspec were less than keen to repeat the job, as they were having to adjust the CNC program for each one.

With many hundreds of hours already invested in producing the engineer’s drawings and CNC machining programs using an original set of TZ crankcases as the template, it seemed the only way forward was to take on the entire manufacturing process here in Australia.

Kerr set about assembling the consortium of companies, all of whom have a passion for the project far beyond just making a very complicated widget, and Consortium Racing was born.

First a pattern had to be made from an original set of TZ750

sand castings. The job was entrusted to the experts at Kelgrif Patterns in Sunshine, Victoria. Kelgrif has been operating since 1969, and boasts over 90 years of combined pattern-making experience on its shop floor. Master craftsman Ted Gorski spent around 650 hours making the timber patterns and the 20 core boxes required to reproduce the TZ750 sand castings.

The patterns then went to Mulholland Foundry, another Victorian company with a long history in producing high quality nonferrous metal castings, including crankcases for some familiar exotic Aussie-built motorcycles: Drysdale and Irving Vincent. Mulholland cast the TZ crankcases in virgin AA601 aluminium, which was then heat treated to T6.

After that, the new castings went back to the company that started this whole enterprise, Milspec Manufacturing, where after 25 hours of CNC machining they were hand fettled in Consortium Racing’s workshop to a finish fit for Yamaha’s former racing flagship.

Finally, the crankcases were vacuum impregnated with liquid Loctite Resinol RTC resin to seal any porosity in the castings. This process is an additional safeguard against a known potential characteristic of sand casting, and one which was not applied to the original parts. You could say this makes the Consortium crankcases even better than the real thing!

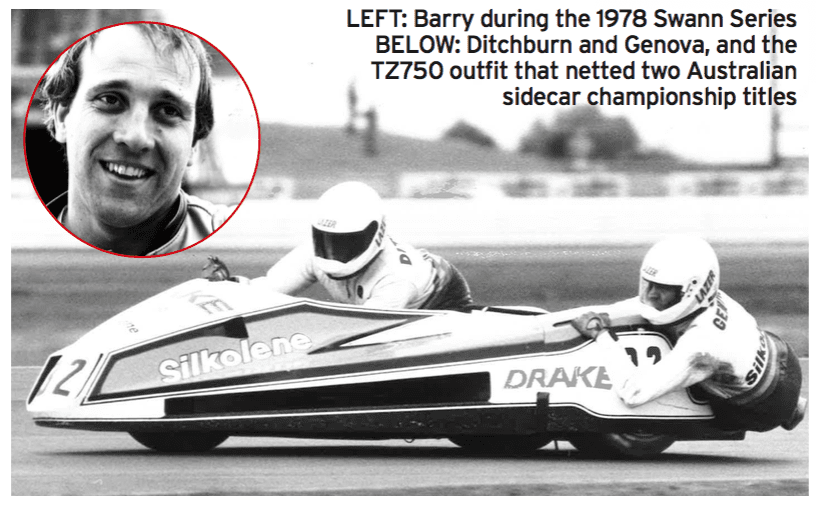

Barry Ditchburn

As well as being a dab hand at building TZ750 engines, Barry Ditchburn has enjoyed significant achievements racing them on both two wheels and three. These machines seem to have been ever-present in his life, and it’s easy to understand why they are so deep under his skin.

In his native England, Ditchburn successfully campaigned TZ750s in the time between and after his two stints as a factory Kawasaki rider. It was during this in-between time that Barry first came to Australia. Reluctantly talked into it by fellow Brit racer Chas Mortimer, Ditchburn shipped his Sid Griffiths sponsored TZ750 Down Under for the first ever Swann Series in 1978. Despite having to borrow a Jack Walters owned TZ when the boat carrying his bike was delayed, ‘Ditch’ went on to make his mark, and decided to move Down Under once his racing days were done.

That seemingly happened in 1982, when he landed on these shores with his family, ready to start a new post-racing life. But among his freighted possessions was an original TZ750D. The part about being done with racing never had a chance.

As fate would have it, the new immigrants would move into the same neighbourhood as AMCN motorcycle racing hall of famer, Barry Smith. This led to an encounter with Melbourne-based motorcycle engineer Bob Martin, which in turn led to Ditchburn becoming involved in the Aussie sidecar racing scene. Soon he was piloting a chassis built by Martin and powered by … you guessed it, his TZ750D. That chassis was replaced by a Ford-Dunn outfit imported from the UK, but still driven by the inimitable TZ750 engine.

In his final year living in the UK, Ditchburn had started racing sidecars nationally – again a TZ – and if it hadn’t been for the fact that all his worldy possessions were already on their way to the lucky country, he says he would have taken up an offer from his former sponsor Ted Broad to contest the world sidecar championship in 1983.

Instead, Ditchburn had to be content with two Australian sidecar championship titles in 1985 and 1989, as well as multiple Vic and NSW state titles, which he and passenger Laurie Genova won in the six years before Ditchburn retired from modern competition in 1990. After parting with his championship-winning sidecar, it later came up for sale, and son Craig convinced his father to buy it. It now sits among the other TZ750 powered trophy winners in the treasured Ditchburn collection.

In the year 2000, after an almost 20-year hiatus from solo racing, Ditchburn entered the world of classic racing along with Craig. They’ve since won many Australian historic solo titles between them. Both have also competed in the International Island Classic.

After all these years, Ditchburn is just as passionate about racing, and completely dedicated to keeping the undisputed king of the two-strokes alive and competitive. There is still a way to go to match the new-breed of 1300cc historic Period 6 four-strokes, but if anyone can make it happen, it’s Team Ditchburn and the team at Consortium Racing.