Thirteen laps remain in the 1976 Australian Unlimited Grand Prix and the chase is on. Warren Willing on his privately entered Yamaha TZ750 is hunting Ikujiro Takai’s works Yamaha 0W31.

Top speeds on Conrod Straight are 290km/h plus and Willing’s 1975 lap record has been knocked sideways. In the final count it will be bettered 45 times. The previous day, he had broken the magic 100mph lap average speed barrier.

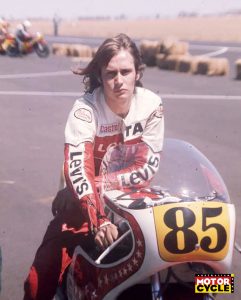

On lap 25, the 23-years-old Sydneysider clocks 2min 15.68secs. If you take 6.172km* as the lap distance, that’s an average speed of 163.76km/h.

Willing’s push builds on the first two parts of his race strategy, having nursed his tyres early on and gained seven seconds with a slick refuelling stop when both riders pitted on lap 17 of the scheduled 30.

Into the last third of the race and the 1974-75 Bathurst winner is cutting the diminutive 29-years-old Japanese rider’s advantage by a whole second on some laps. But he also feels the frustration of losing rhythm and hence time.

Does he have sufficient laps? The temperature is dropping and the atmosphere is tense as dark, heavy clouds roll over the Mountain.

Suddenly the circuit is drenched and officials have no option but to flag the race after 28 laps. Takai wins, three seconds ahead of Willing, with Kawasaki factory rider Masahiro Wada third and New Zealand’s John Woodley fourth on his Suzuki RG500.

Kawasaki’s main hope, Gregg Hansford, finishes ninth – after a troubled weekend that saw him switch between the recently introduced water-cooled KR750 and air-cooled H2R.

An incredible race to be sure.

The Red Rocket’s new lap record stood until Graeme Crosby dipped into 2m 13s territory on Easter Saturday 1979.

The back story was amazing too. In addition to Takai on the latest factory 750, Yamaha sent Giacomo Agostini’s 1975 0W29. But it sat unused on the two race days.

Willing only contested the 1976 Easter meeting when his hopes of a European season fizzed. His machine, entered by long-time sponsor Adams & Sons Motorcycles, featured a mono-shock/cantilever chassis made to his requirements in the Sydney suburb of Cabramatta.

Where is it now? Good question. Willing sold it to Victoria’s Greg Johnson early in 1977. He raced it locally for one season and it is believed he sold it in England in 1978. (Johnson has been incommunicado for years, so we have no clues the fate of this landmark machine.)

It is something of a misunderstood bike, an identity crisis almost, often confused with the 0W29, which was handed to Willing for the second half of 1976 season and then returned to Japan.

Some of the confusion stemmed from Willing taking two cantilever chassis 750 machines to all his second-half 1976 engagements for the Yamaha Dealer Team, both with star-pattern fairings – the 0W29 and his locally developed machine.

Willing rode both in 1976 and Greg Johnson rode both in the space of six weeks at the beginning of 1977.

Even with matching fairings, the 0W29 can be identified in photographs by its shorter exhausts (at most meetings), and distinctive rear disc-brake layout.

To explain fully, we probably need to begin at Easter Bathurst 1975. Willing won that weekend with his Yamaha sporting laid-forward rear shocks, a tweak American rider Hurley Wilvert showed him.

Hansford had just come into the Team Kawasaki Australia fold, but crashed his H2R during practice at Bathurst, sustaining a broken wrist and thumb. Once recovered, he dominated the remainder of the year, securing his third successive national championship. In the summer, he challenged Pat Hennen (Suzuki) in the New Zealand International Series.

Hansford’s new KR750 arrived in time for the 1976 Australian TT at Laverton. He won the Unlimited TT, after a great battle with Hennen, with Willing a lonely third.

Contrasting Hansford’s stellar second half of 1975, Willing had a limited Formula 750 program. He spent all of August and September staying at Kel Carruthers’ home in San Diego, recovering from a back injury sustained when a 250 rider crashed in front of him during a practice day at Laguna Seca and preparing for the AMA National at Ontario, California.

When Willing did ride his Yamaha in 1975, he impressed. He was fifth (first private entrant) at Daytona, won Bathurst, took a fourth place in one of two races at Ontario, and a 9-3 result at the Indonesian GP.

Looking to 1976, Willing had commissioned a mono-shock chassis. Chris Dowde did the bulk of the fabricating in Peter Campbell’s workshop in Cabramatta, using chrome-moly tube for the chassis and chrome-moly sheet for the swinging arm.

“As things happen in motor sport, works expands to fill available time and things go on until the last minute, but we did have time for a test before the first race,” Dowde said. Peter Campbell said they also converted a 750 to cantilever rear suspension for Ken Blake, using the existing frame.

Dowde said Willing had firm ideas on what he wanted – “we just did the work”. The whole bike would reflect Willing’s learnings from two seasons riding a Yamaha 750. Some reports credited Kel Carruthers with input, but the 1969 world 250 champion told the author he “had nothing to do with that bike”.

The mono-shock configuration increased rear suspension travel, while the triangulated swinging arm increased rigidity. At Willing’s request, the engine was positioned further aft in the chassis than on a standard TZ750, to optimise traction. In 1974, when Willing first rode a TZ750A at Bathurst, he thought the clutch was slipping as he accelerated onto Conrod Straight. Then he realised the four-cylinder racer was wheel spinning.

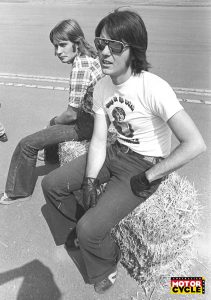

After the February 8 Laverton meeting, Willing flew to the USA with high hopes. Before departing he pitched for sponsorship from jean company Levis to contest the FIM F750 series. His mechanic would be George Vukmanovich, who had worked with Wilvert.

Willing’s plans began to fray when Vukmanovich’s hip collapsed and he had to go to hospital, and that didn’t help the sponsorship deal. Willing meantime had acquired more bikes. “Kel offered me a 250, 350 and a spare 750 for Europe,” Willing said.

“So I prepared two 750s in San Diego, went to Daytona and just wore myself out trying to do all the work myself. All week I seemed to have the best engine in the worst frame. I ended up falling off in the race.

“From Daytona, I went back to the West Coast and shipped the bike off to the next F750 round in Venezuela. At least I thought I’d shipped it off! I arrived in Caracas, but my bike didn’t. It hadn’t been loaded in Los Angeles, because the ground staff smelled fuel in the explosion-poof foam in the tank. That just topped things off after the sponsorship falling through and Daytona!

The Venezuela race, held on March 21, was such a debacle it was expunged from the F750 series, a decision that cost America’s Gary Nixon (Kawasaki) the crown.

Europe hopes dashed, Willing shipped his bespoke 750 home for Bathurst, arriving barely a week before the April 16-19 meeting. He linked up with Alan Adams set about not so much flying under the radar as doing his own thing. By this stage Willing’s bike had different exhausts to those seen at Laverton, with long, thick mufflers blended into the pipes (see Bathurst photos).

Mount Panorama had changed too. The 1.9km Conrod Straight had been resurfaced. In 1972, Conrod was still heavily crowned country road. The new surface boosted top speeds even further. Replacing the previous bumpy patchwork surface in the dip outside the drive-in theatre meant riders could carry full throttle there, because they were no longer fighting for control. Add new machines and new tyres, and it only needed favourable weather for lap records to tumble.

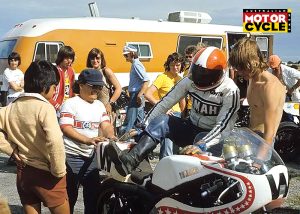

Meantime, Yamaha pulled out all the stops to combat Hansford and Kawasaki, sending 0W29 and Takai on the 0W31, the latest word in F750 racers and the most important Yamaha racer sent here since Alan Osborne rode an RD56 disc-valve 250 GP machine in the mid-1960s.

The 0W31 was smaller, lighter and more powerful than the 0W29 and had much of the look of Agostini’s 1975 500 championship winning Yamaha 0W23.

The 0W29 was ear marked for an Australian rider, but whom? Leading Victorian Bob Rosenthal said local management drew up a list of candidates and ruled out those with links to Kawasaki or Suzuki. (Willing was not expected to be in Australia.)

Top of the list were Rosenthal and rising Queenslander Stephen Klein. The managers ruled that whoever was fastest on their regular 750 in early practice would ride the 0W29.

This had the potential for a sad outcome and soon did. Klein locked his front brakes at 200km/h on the entry to McPhillamy Park Bend and cannoned feet-first into the metal fencing. He sustained a broken leg and crushed one vertebra. He was in hospital for a total of five months, had one disc removed to relieve pressure on his spine and struggled to return to his job as a carpenter. He made a brief comeback to racing in 1977.

Rosenthal now had the 0W29 and, working with Rod Tingate, set about sorting it. Rosenthal said the machine had TZ750C forks, brakes and frame, with cantilever rear suspension grafted on. The cylinders had six transfer ports compared with four in the standard cylinders.

“Agostini, being small guy, the foot rests had been moved 25mm higher. To my mind, this made the bike feel nose heavy,” he said. “The front end was set up way too steep. The bike tended to sit up and head for the outer fence when lightly trail braking.

“Really good fun around the top of the Mountain or trying to slow up a bit through the Esses! It was a pig in that respect, albeit a very fast one – the fastest bike I ever rode.”

Then things went from bad, with Klein’s injuries, to terrible. Late on Friday afternoon, Rosenthal’s brother-in-law Ross Barelli died in a crash at Murrays Corner. An after-market disc rotor on his Suzuki RG500 had shattered, leaving him with no front brakes. Rosenthal withdrew from the meeting and never raced at Bathurst again.

Takai had qualified fastest at 2m 19.52s, fractionally short of the magic ton and 0.12s quicker than Hansford, with Willing third, then Rob Hinton on his private Yamaha, Rosenthal on the 0W29, Murray Sayle (Kawasaki H2R) and Wada. The top three were all on American Goodyear tyres.

Hansford’s qualifying time was competitive, but he was in a quandary over of his equipment. Team boss Neville Doyle modified some KR cylinders for Saturday’s 15-lap race.

The Queenslander carried the fight to Takai early in the race, as they pushed the lap record through the 2min 20s barrier. Using Hansford’s slipstream, Takai gained an additional 5km/h and ripped through the speed trap at 300km/h, making the 0W31 the fastest road-racing vehicle yet seen in Australia. Back then, only Donald Campbell’s Bluebird gas-turbine land-speed record car and drag-race cars had gone faster in Australia.

Even with a 20km/h speed disadvantage, Hansford regained the lead and led for three laps, before retiring on lap five with a broken gear lever. Takai now led comfortably from Hinton and Wada.

Meantime, Willing was recovering after stopping at the beginning of lap two to adjust his clutch throw-out mechanism. He rejoined the race a lap behind Takai, but with his machine now running superbly. He had half an hour of racing to regain positions and gather information for Sunday.

Willing was soon lapping in familiar style – smooth, relaxed and deceptively fast. His best lap was 2m 17.92s – almost six seconds under his 1975 lap record and Bathurst’s first 100mph motorcycle lap. He passed Takai and hence unlapped himself.

Takai was under no threat in terms of race position, 24 seconds ahead of Hinton, but he upped his pace when passed by the local hero.

Willing was officially classified 14th, even though he ran out of fuel on the last lap. His machine had showed good straight-line speed, clocking 290km/h compared with Takai’s 295km/h when it didn’t have a ‘tow’.

The Australian Unlimited GP was the second race after lunch on Sunday. Hansford and Doyle were still unhappy with the KR750 engine and raced the H2R. The switch didn’t work as planned, with Hansford left in Takai’s wake the first time up Mountain Straight and drifting back to finish ninth.

Up front, Takai led from Willing and Hinton, until a deflating front tyre brought Hinton unstuck at the top of Mountain Straight. This promoted New Zealand’s John Woodley to third on his Suzuki, tailed by Japan’s Sadeo Asami (Yamaha), Wada and Sayle.

Pit stops began on lap 14, with the Kawasakis in first. The Adams & Sons crew were well experienced in rapid refuelling in Castrol Six-Hour races and Willing’s stop was quicker than the works mechanics managed on lap 17.

The race then played out as described at the beginning in the story. And don’t let anyone tell you these two-stroke racers lacked aural quality. The author watched this race from Pit Straight and Hell Corner, with vivid memories of the top four machines winding out on long gearing into increasing gloom on Mountain Straight. Each had a distinctive note – the Takai and Willing Yamahas, Wada’s triple and Woodley’s high-pitched four.

Willing had missed the two rounds of the national championship series, but gained maximum points at Bathurst as the first local rider to finish.

“After Bathurst, I spoke with (NSW Yamaha distributor) McCulloch and directly with Yamaha, via an office established in Sydney,” Willing said. “We did a sponsorship deal with Levis and formed the Yamaha Dealer Team. In 13 races, I had one break down with the Agostini bike…and went straight out on my spare.”

Willing won the 1976 national championship, with his brother-in-law Murray Sayle second. The Red Rocket then packed up the 0W29 to return to Japan, but Rosenthal rode it at Calder and Greg Johnson in the New Year’s Day 1977 Phillip Island meeting.

Willing had advertised his machine for sale, ready for collection after November’s final Oran Park F750 Pro Series round in November.

However, he took it to New Zealand in the summer, finishing second to Hennen (Suzuki 500) in the ten-race International Series. It would even closer if Willing had not stuck his arm on a chicane marker during the first round at Pukekohe.

As a minor but eventually notable side story, Willing let a retired English rider then living in NZ test ride the bike. Said rider had to be helped to get his right leg over the bike due to a fused right ankle from an F1 crash. He was, of course, Mike Hailwood. Eighteen months later, he made a fairytale return to the Isle of Man.

Events now moved quickly again. Willing sent the bespoke 750 to Greg Johnson and revived his plan to go to Europe, with partner Wendy and mechanic Vukmanovich. He ordered a Yamaha TZ750D. He chose Europe over a tempting offer of a works Yamaha to race locally and Yamaha gave him $5000 to boost his private budget.

Johnson won the opening round of the national championship at Symmons Plains in February 1977 on the ex-Willing bike, taking the race lead when the centre spark plug in Hansford’s Kawasaki dropped its electrode.

The first TZ750D arrived in Australia soon after. It was the volume-production versions of the mono-shock 0W31, without the exotic cycle parts and six-port cylinders. A brilliant machine, with good power, handling and brakes. Doyen technical writer Kevin Cameron reckons it was the best racing ever sold and that it gave many riders their careers back, after struggling with the twin-shock TZ750A, B and C models. If that wasn’t enough, it worked on Dunlop, Goodyear or Michelin tyres.

Jeff Sayle rode one to win the 1977 Oran Park Pro Series and 1977-78 NZ series, and posed a serious challenge to Hansford in national championship.

Rosenthal loved his and reckoned the 0W29 engine in a TZ750D chassis would have made “a formidable weapon”.

Willing rode his TZ750D at Daytona finishing sixth, two places behind Hansford. He contested the full European season, riding it as a 750 and in two GPs as a 500. In the 1977-78 NZ Series he was third, behind the Sayle brothers. Surely the only international series where the top three had attended the same school, Macquarie Boys High.

With hindsight, he wished he had gone to Europe in 1976 with the bespoke bike, “because in ’76 I would have been one of the few private entrants with a cantilever chassis.”

According to Campbell, Willing reckoned Bathurst in 1976 was the best it ever worked. “It had great traction.”

WORDS // DON COX

PHOTOGRAPHY // DON COX & AMCN ARCHIVES