Phil Irving was adamant: “V-twins: the only practical alternative to the single,” he wrote as the heading of one of the popular columns he wrote in the 1970s.

Republished a few years later in his book Rich Mixture, Volume One, Irving laid out a theory that negated the decades of development and hundreds of thousands of British parallel twins manufactured and sold from the late 1930s.

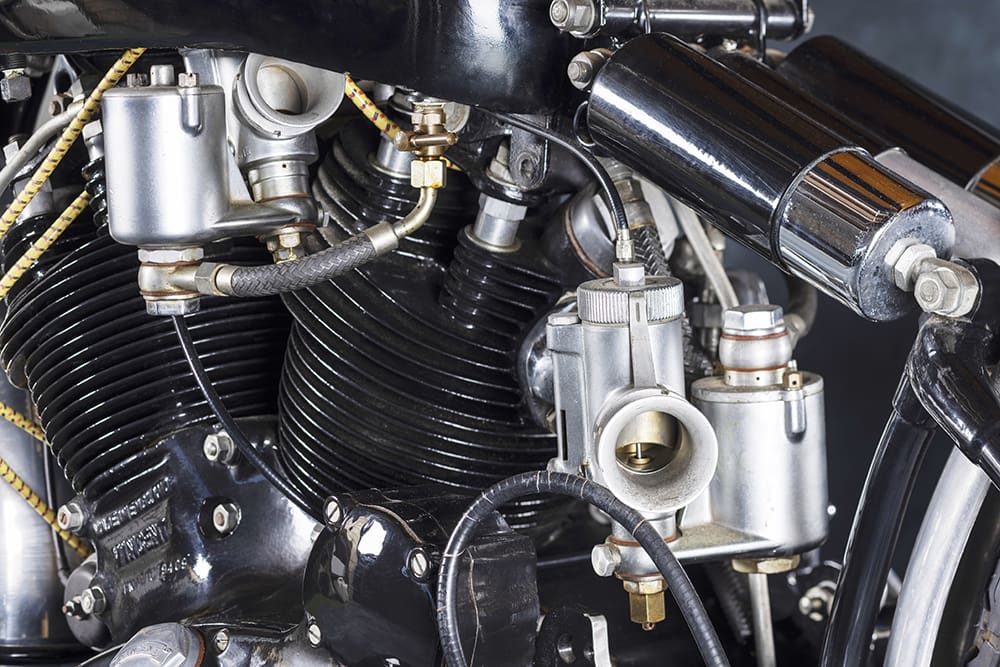

“The only practical alternative to the single-cylinder engine was a twin made by bolting two similar cylinders in “V” formation onto a crankcase which was larger in diameter and little, if any, wider than the single-cylinder version as both conrods ran on a single crankpin,” he wrote.

“This was easily the most logical thing to do, because the resulting engine could be fitted neatly into the same frame. It need be only 50 percent heavier for double the capacity and possessed much better balance than either a single or a parallel twin and therefore gave smoother running without excessive complication.”

He went on to accuse Triumph of leading the major manufacturers down the parallel-twin sales path. Even Norton, which he noted had won the first Isle of Man TT race in 1907 with a V-twin.

“In many respects, the parallel twin is technically inferior,” he concluded.

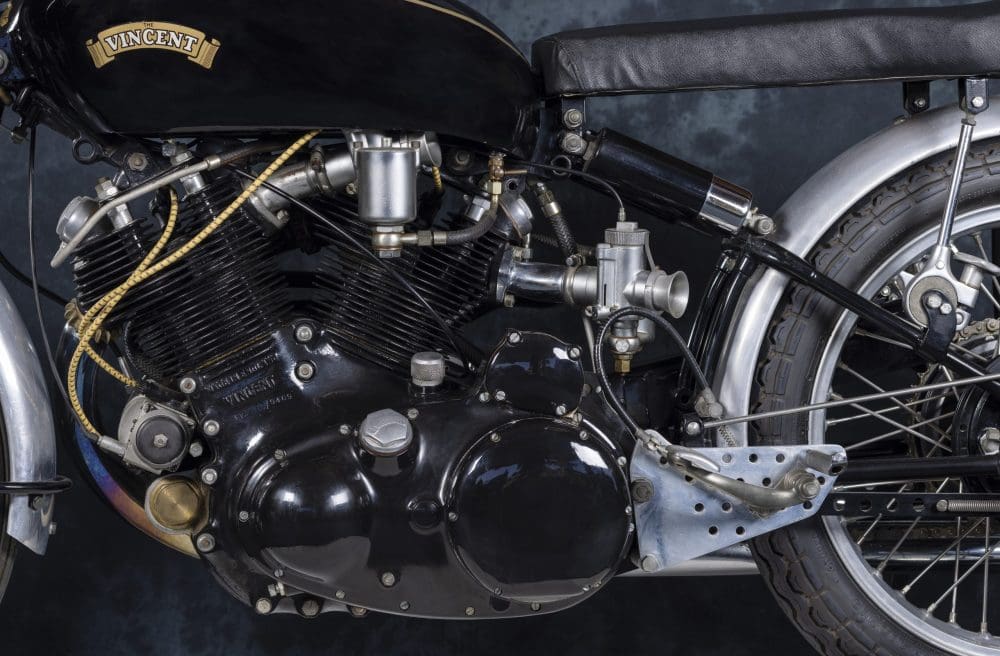

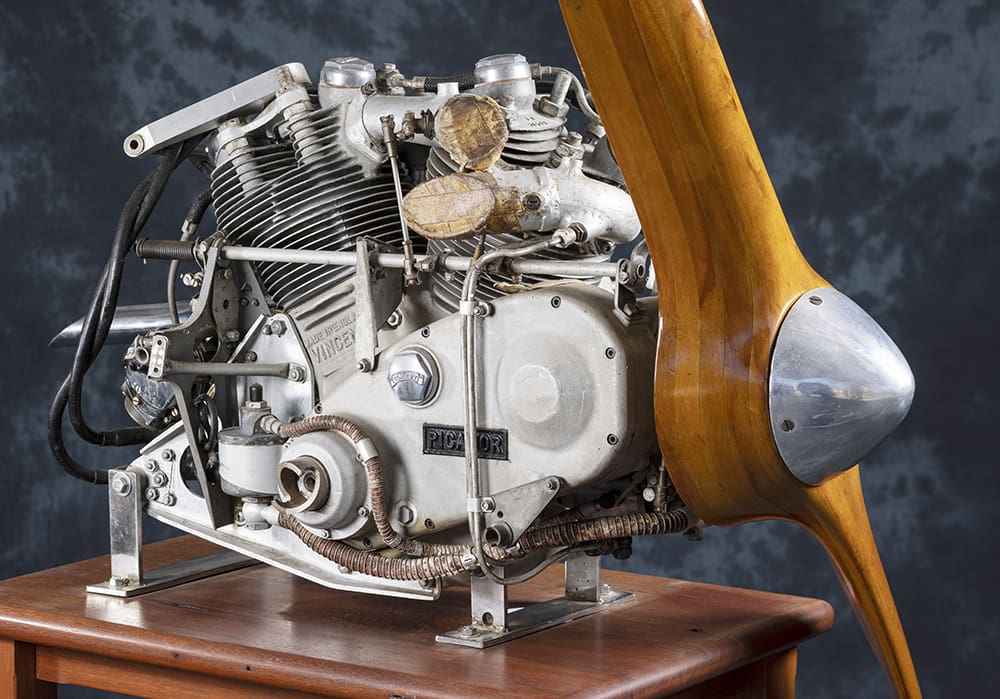

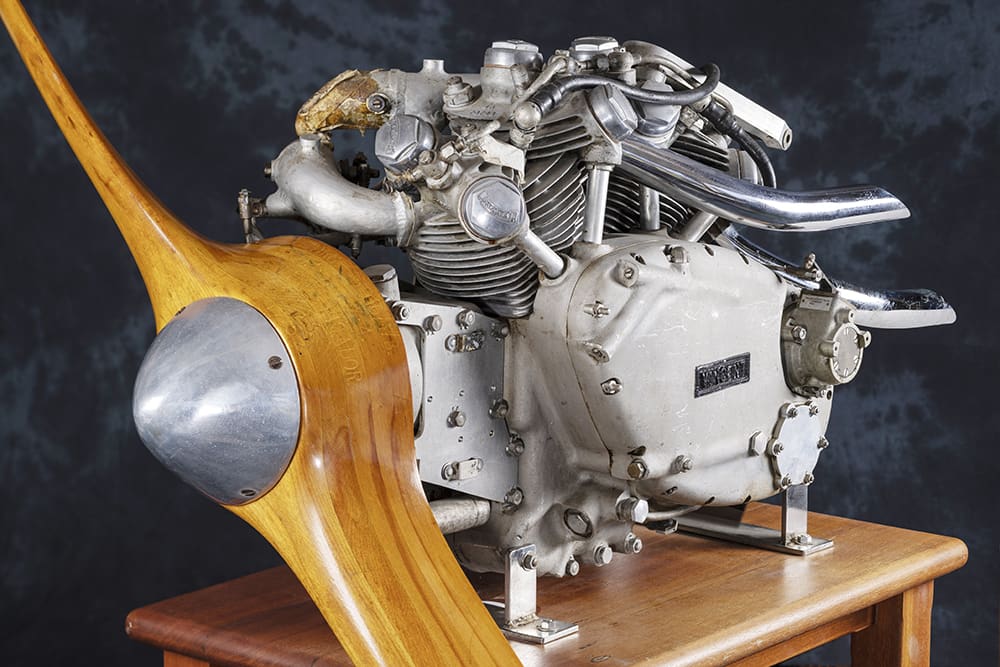

Every motorcycle enthusiast knows Phil Irving’s role in the development of the Vincent. The Black Lightning was the peak of his V-twin engine design theories. It was also his swansong, as the company went into receivership just a year after it was launched in 1948 and Irving left soon after.

The company struggled on until its final collapse in 1955, while Irving’s design career continued on his return to Australia and spanned many other areas over the next two decades. Everything from a compact, reliable, low-cost, world-beating F1 V8 car engine to a six-litre Chamberlain flat-twin diesel tractor engine are included in his portfolio of work.

However, his Vincent efforts with the Black Lightning have made it an almost mystical motorcycle. This is based on its performance, very limited production numbers and that timeless and famous photograph of Rollie Free’s record-breaking run at Bonneville in 1948 on what is considered a prototype of this rare model.

The world’s fastest production motorcycle in the late-1940s-early-1950s, the Black Lightning was often compared to the fastest production car of that time, Jaguar’s XK120.

It was launched in November 1948 at London’s world-famous Earl’s Court Show, which had returned for the first time since 1938.

The race-ready Black Lightning was the star of the new Series C models, which featured Vincent’s own in-factory-built Girdraulic front forks and rear hydraulic suspension. The Black Lightning, the latest in a model line that had started with the Rapide and progressed to the Black Shadow, was one bookend for the Vincent range, with the single-cylinder Comet the other.

The theory Irving laid out in his 1970s column reflected the lateral thinking that had created the first Vincent. In basic terms, the Comet’s cylinders, heads and valve train could be fitted to the V-twin’s crankcases to keep costs down. In fact, Irving’s first Vincent V-twin of the mid-1930s was even fitted to a slightly modified Comet frame confirming how compact the V-twin design was.

The Black Lightning was the equivalent of today’s handbuilt factory world Superbike racers. Polished and tuned engine internals produced 25hp more than the Shadow’s 70hp, while lightweight aluminium parts, including the rims, shaved 100lb (45kg) off the Shadow’s 380lb (170kg) overall weight. A choice of compression ratios, as high as 12:1 for methanol, were fitted, along with Irving’s ‘Mk II cams’. Careful assembly and head porting ensured both longevity and high performance.

The example featured here has a history that in many ways sums up the Black Lightning’s story and underlines why motorcycles built for racing never stay original for long. It was bought new in 1952 by flamboyant Grand Prix car racer Prince Bira of Siam from a Singapore Vincent agency.

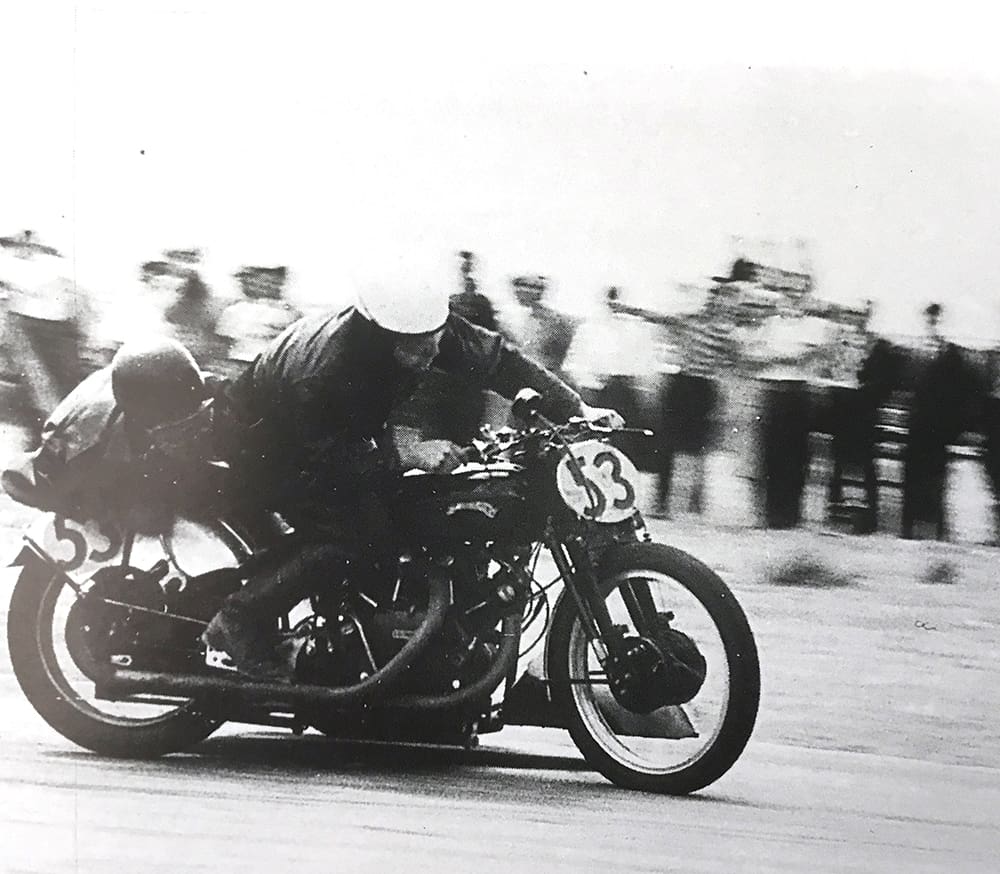

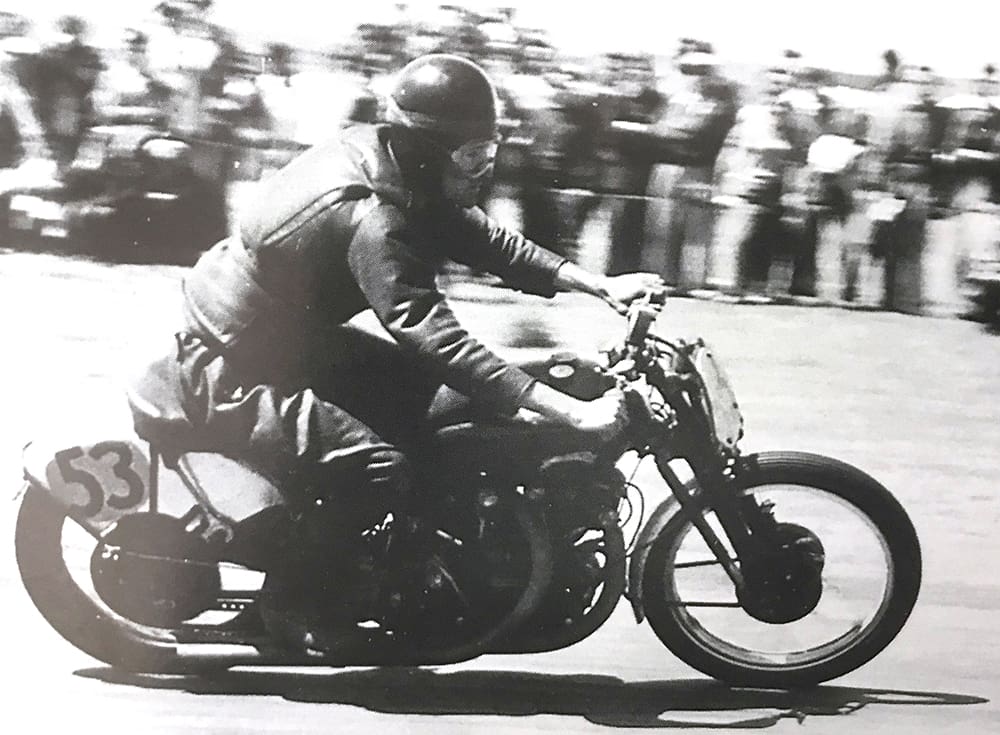

Eton-educated and one of the ‘gentleman racers’ of Grand Prix, Prince Bira appears to have bought the Black Lightning as a plaything. It sat around for a year or so before Australian motorcycle racer Gordon Benny acquired it. Benny certainly was no Prince Bira. Working at the time on an oil tanker, he brought the Black Lightning back to his home state of South Australia as baggage, fitted a sidecar to it and went racing.

This involved both tarmac and speedway events, where it won major races, including the 1957 South Australian Sidecar Grand Prix. Benny would also take the sidecar off to allow his passenger Dean Hogarth to race solo events.

The engine ended up in West Australian Tom McQuade’s speedway sidecar outfit. McQuade, a legend of the sport also regarded as a mentor to other riders, kept the outfit until fellow West Australian Ian Boyd acquired it.

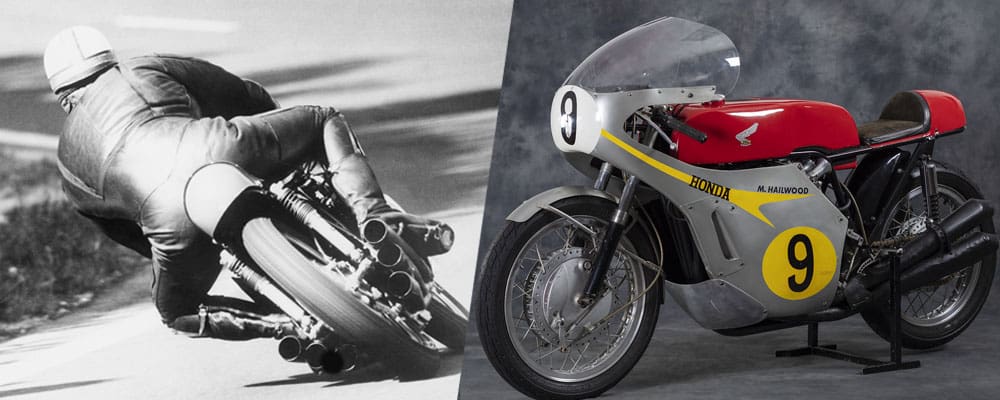

“I call it David’s restoration,” says Boyd, who has one of the world’s largest collections of Vincents. He is referring to David Bowen, whom Boyd regards as one of the key world figures in the revival of Vincents as a collectable motorcycle. Bowen died last year in his long adopted home of South Australia, aged 88 years. He had started off as a Vincent apprentice in 1949 alongside a young John Surtees. Both their fathers had worked at the factory.

“It took only a few moments of conversation with David to know he was a genuine person and one I could trust,” says Boyd, explaining how he enlisted Bowen to help with his restoration projects.

Typical of many Vincents that had spent a couple of decades in speedway racing, Boyd had to source the original frame and other key components.

“Fortunately racers like Tom McQuade never threw anything out as they never knew when they might need it,” he says.

But how do you turn such a rare motorcycle back to original?

Boyd’s answer shows he has a realistic approach to Vincents, their restoration and what is considered ‘factory original’.

“People forget that buyers could order what they wanted and that as the factory bought in parts when they ran out of eight-inch headlights, they might reach up on the shelf and pull down a six-inch one and fit that,” he says.

What left the factory may not have been exactly what was in the sales brochure, as is proved by the fact that when the Vincent trademark succeeded HRD, some of the new range sported crankcases stamped with HRD as the factory used up old stock.

“What is factory original, anyway?” asks Boyd. “As soon as you modify the riding position or even put a different brand of tyres on when the first lot wear out, it’s not factory original anymore.”

He also disputes the claim that only 34 Black Lightnings were built and has the evidence to back it up.

“The drag bike I have was built at the factory and not recorded, as was John’s Penn Black Lightning,” he says.

South Australian Penn, a factory employee who drowned while testing a Vincent Amanda watercraft, a precursor of today’s jet skis, had built up a potential record-breaker.

It was shipped home to Adelaide after his death. Although crashed during a speed attempt on Lake Eyre in 1962 it remains in the Penn family and within the past decade has appeared at Australia’s Lake Gairdner’s speed week.

Adelaide was a strong sales outlet for Vincents. A lot of this was due to local importer Sven Kallin, who negotiated directly with the factory every year. This involved regular six-week voyages to the UK but the result was at least two Black Lightnings being brought back and sold in South Australia.

So a rare motorcycle, even at that time, but available if you made the effort to secure one.

Words HAMISH COOPER Photography PHIL AYNSLEY