For the last century or so we’ve seen remarkable developments in motorcycling and road transport as a whole. But over the next decade some of the fundamental elements that have remained constant throughout that time are set to be shaken up.

Technological improvements and ever-increasing governmental interference in the construction and use of all types of vehicle, as well as the road networks they travel on, allied to societal changes in the way we use road transport, will conspire to make riding a different experience.

Not necessarily worse, though; the essential freedom that motorcycles have represented ever since their inception will become increasingly valuable as other vehicles get more autonomous and restricted. Far from leading to a motorcycling decline, if the cards fall right then the changes we can expect to see over the next decade or so could lead to a new heyday in two-wheeled transport.

Euros and Beyond

The Euro4 emissions regulations may have only come into force at the start of 2017 but we’re already on the verge of the next generation of emissions limits.

The Euro5 levels are set to be adopted across much of the world, not just Europe, with countries including Australia and Japan also using them as the basis for future limits. As a result, they’ll dictate the design of the next generation of new bikes.

The limits include reductions in all types of pollutants compared to Euro4, and as such represent a new challenge for engine designers.

They’re set to have a staggered introduction, with all newly designed bikes introduced from January 2020 in Europe needing to meet them. Existing designs need to be updated to conform by the start of 2021, although, as with Euro4, it’s likely that manufacturers will be able to obtain an additional two-year period of grace to sell off older models, with the last Euro4-legal bikes sold new at the end of 2022.

Those deadlines are soon; considering it takes around five years to develop a new bike from scratch, everything that’s currently being worked on must meet Euro5, although we’ve yet to see a single production bike launched that’s designed to comply with them.

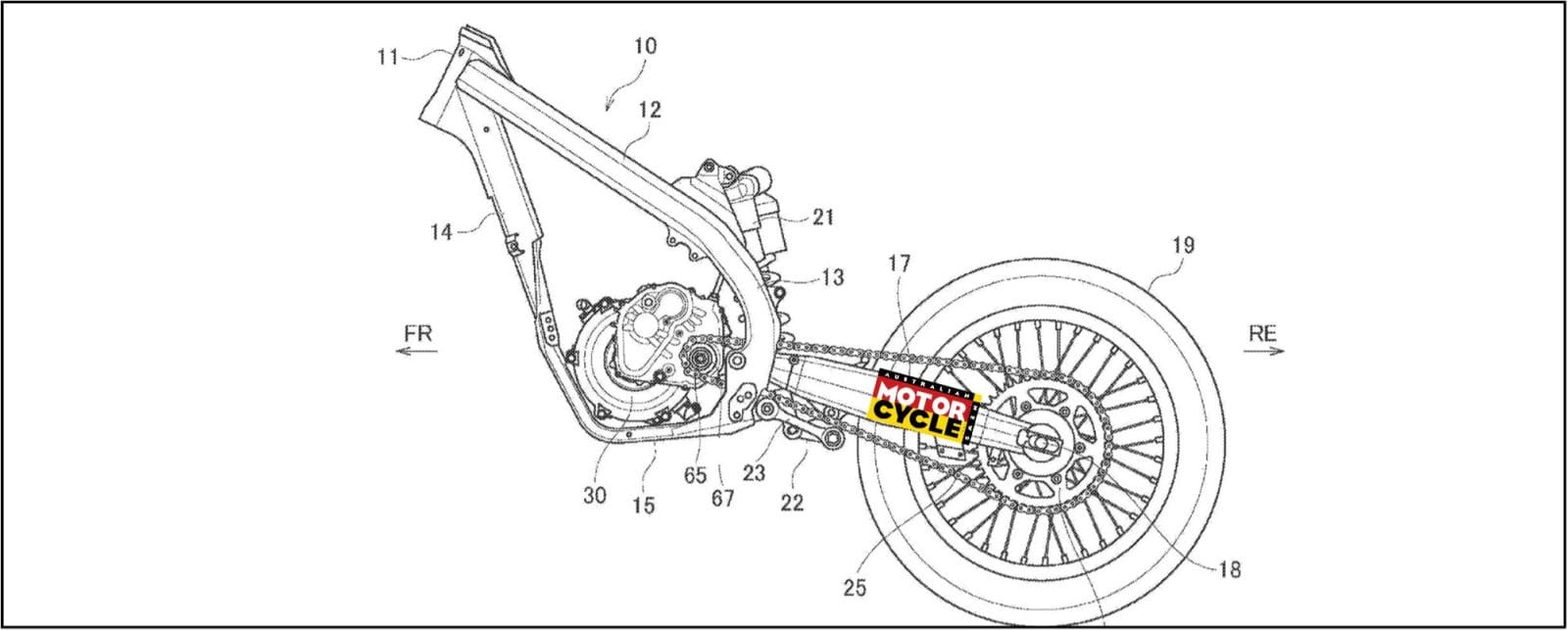

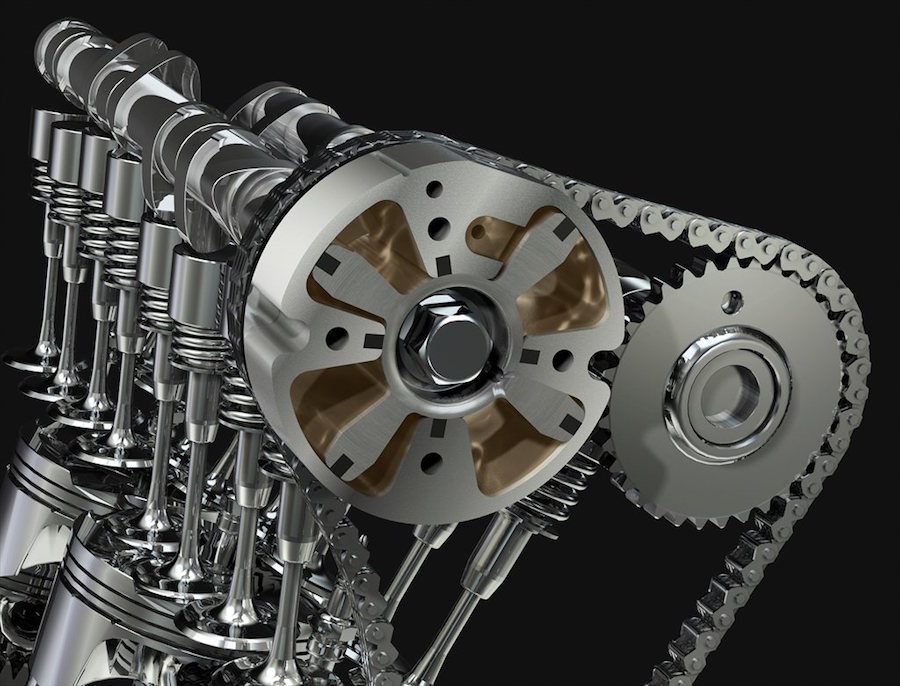

Air-cooled engines will be under yet more pressure as the difficulty in maintaining constant temperatures within them makes it hard to use the sort of tight tolerances that liquid cooling allows. And high-revving, high-performance engines will also find it increasingly hard to meet the limits unless they adopt technologies like variable valve timing to increase valve overlap at high revs and reduce it at lower engine speed.

Electric Bikes

However tough Euro5 emissions limits might be, they’re still only a stopgap. Eventually bikes will have to meet even stricter Euro6 rules, although no timescale has been confirmed on that. But with several European countries already planning an outright ban on the sale of new fossil fuel-powered road vehicles from 2040, and certain cities looking to ban their use even sooner (petrol bikes are already banned in some parts of China), the future lies in electric bikes.

And if manufacturers are to have all-electric ranges by 2040 they’re going to have to start getting very serious about the technology during the 2020s.

So far we’ve seen tentative moves from major firms. Harley’s LiveWire, Honda’s new PCX Electric scooter and BMW’s C-Evolution are steps towards electric bikes, but none of the established companies has yet tried to create a battery-powered bike designed to tempt the bulk of motorcyclists away from their combustion engines. In cars, there’s a much more distinct move; electric machines like Teslas and the Jaguar I-Pace are desirable in their own right. And increasingly impressive high-speed charging systems are going some way to eliminating the range anxiety that’s often cited as the biggest electric vehicle turn-off for buyers.

In bikes, Honda’s PCX Electric uses a hot-swappable battery system; you just pull out the flat one and slide in a fresh battery. Yamaha is also pursuing this idea with its upcoming electrics, derived from the PES and PED concept models shown in recent years. Kawasaki has also been working on developing an electric bike with a swappable battery.

Suzuki, meanwhile, has been following a different route. Unlike most of its rivals, it’s still a firm fan of hydrogen fuel cells, which convert hydrogen and oxygen into electricity and water. They have the advantage of being quick to refuel – filling a tank with hydrogen replenishes their range – but need a completely different infrastructure in terms of refuelling stations.

Indian, KTM and BMW are also all hard at work on electric bikes, so we can expect a thriving and competitive electric bike scene within a few years.

Read the full story in the current issue (Vol 67 No 17) of AMCN on sale now