“We ARE rocket scientists” – so reads the slogan on the sweatshirt of Robin Tuluie. In fact, Tuluie was originally an astrophysicist before he moved to Mercedes-Benz in 2011 and became a key figure in its current domination of grand prix racing. You might say he is partly responsible for making Formula 1 even more boring nowadays than it already was before, just by being so bloody good at his day job.

Tuluie, 51, was born and brought up in Germany, where his Iranian-born dad sold Persian rugs before emigrating to California to grow avocados. Robin graduated from University of California, Berkeley, and then studied for his PhD, but at the same time he was getting hooked on motorcycles. So great did this passion become that in 1996 he left off trying to figure out how galaxies were created to become chief chassis engineer for Victory Motorcycles, then being concocted by America’s largest manufacturer of snowmobiles and ATVs, Minnesota-based Polaris Corp. By this time Tuluie had already started road racing, first on an elderly Norton twin, then on his first self-made special, a two-stroke single powered by a CR500 Honda MX engine that produced 51.5kW in an 87kg motorcycle. He piloted this to two national championships in 1995 and 1996, including a win at Daytona.

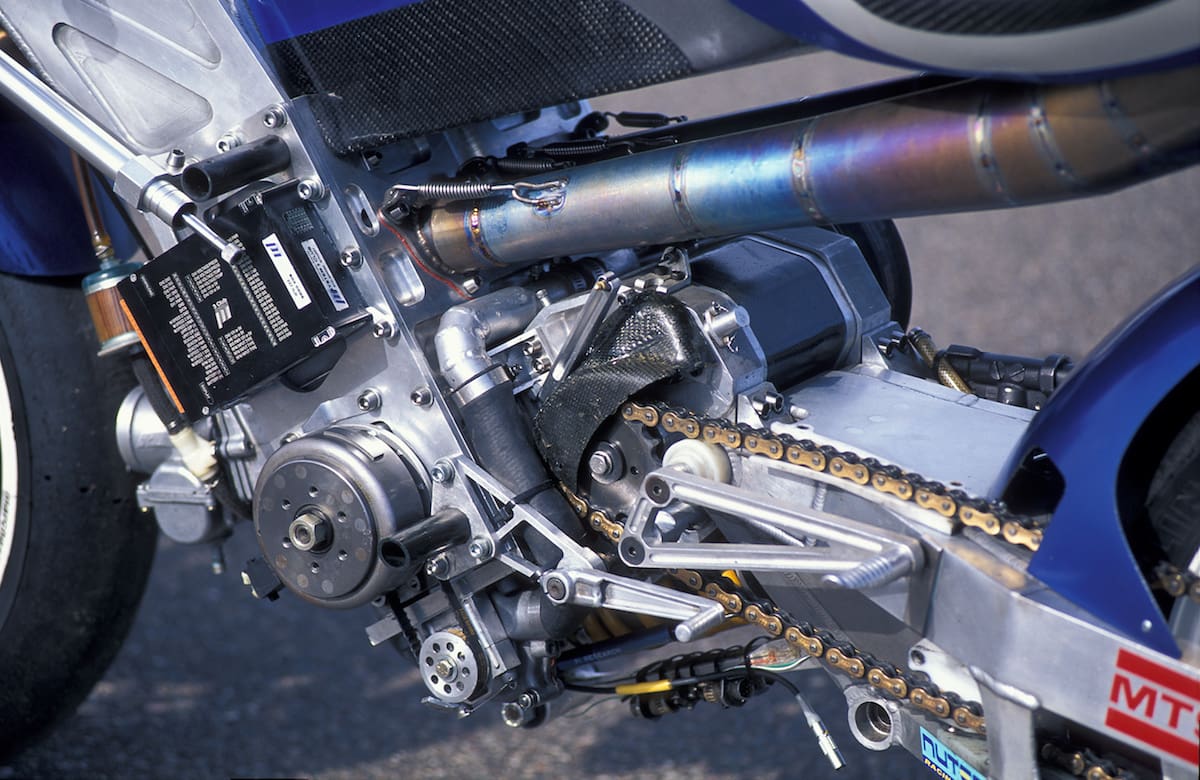

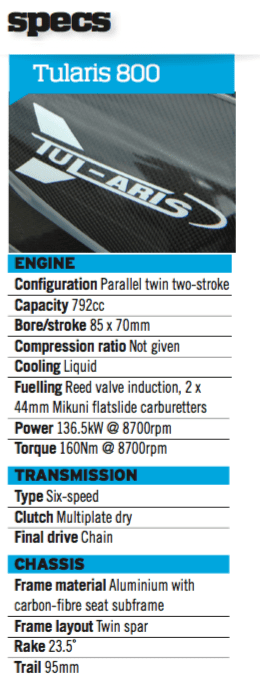

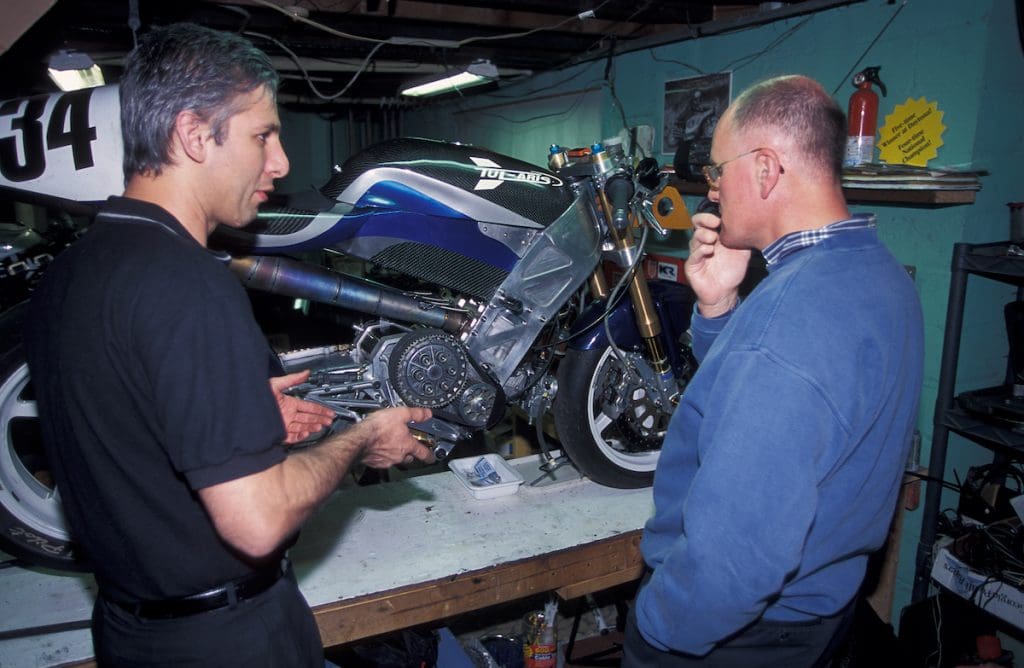

But then in 1997, during the day job at Polaris, Rocket Man Robin came across a prototype snowmobile motor which sent his fertile imagination into overdrive. Three years and countless hours of hard graft later, he manoeuvred the end result of his labours out of the cellar of his house in suburban Minneapolis, where he and a small team of helpers had created a Y2K work of two-wheeled art, essentially unlike any other motorcycle yet devised. After all, there are not many racers ever built – not even for the Formula USA anything-goes category – that are based on a twin-cylinder 792cc two-stroke snowmobile engine, wrapped in a state-of-the-art aluminium twin spar chassis with carbon-fibre seat subframe, to create a bike weighing just 124kg straight out of the cellar.

Only one thing wrong – well, two really. One, Tuluie rode the bike in a shakedown test at Daytona in March 2000, in which he realised that despite winning four AHRMA National titles he’d earned in amateur road racing, he was not qualified to tame this basement bombshell. Two, he’d just switched jobs to the extremely demanding, albeit rewarding role of developing the ultra high-tech MTS seven-poster test rigs used by Formula 1 and Indycar teams. “I figured it was better to hold back on the riding, and concentrate on developing the Tularis to what I hoped would be race-winning level in the hands of a pro rider,” says Robin. So that’s exactly what he did…

His snowmobile-powered racer capped a series of regional race wins and top-three national race finishes by finally defeating the horde of GSX-R1000 Suzuki ultrabikes and 500cc Honda V-twin GP racers to win a round of the Formula USA series in the hands of hired hand Robert Jensen. Things were looking up for the rocket racebike. But then Robin got an offer he couldn’t refuse – to relocate to Britain to become Head of R&D at Renault F1, taking the Tularis 800 with him.

In 2005, the first full year after Tuluie joined them, the Renault Formula 1 team swept Ferrari off its pedestal. Young Spanish driver Fernando Alonso was crowned World Champion, and repeated the feat the following year in 2006. The team’s constant lab work and on-track testing certainly played a part in this success. And at one such track test, Robin rolled out his ring-ding racebike to allow a mate of his enjoy a few laps before it got tucked up for the winter in the stable beside the stream. And I enjoyed doing so very much.

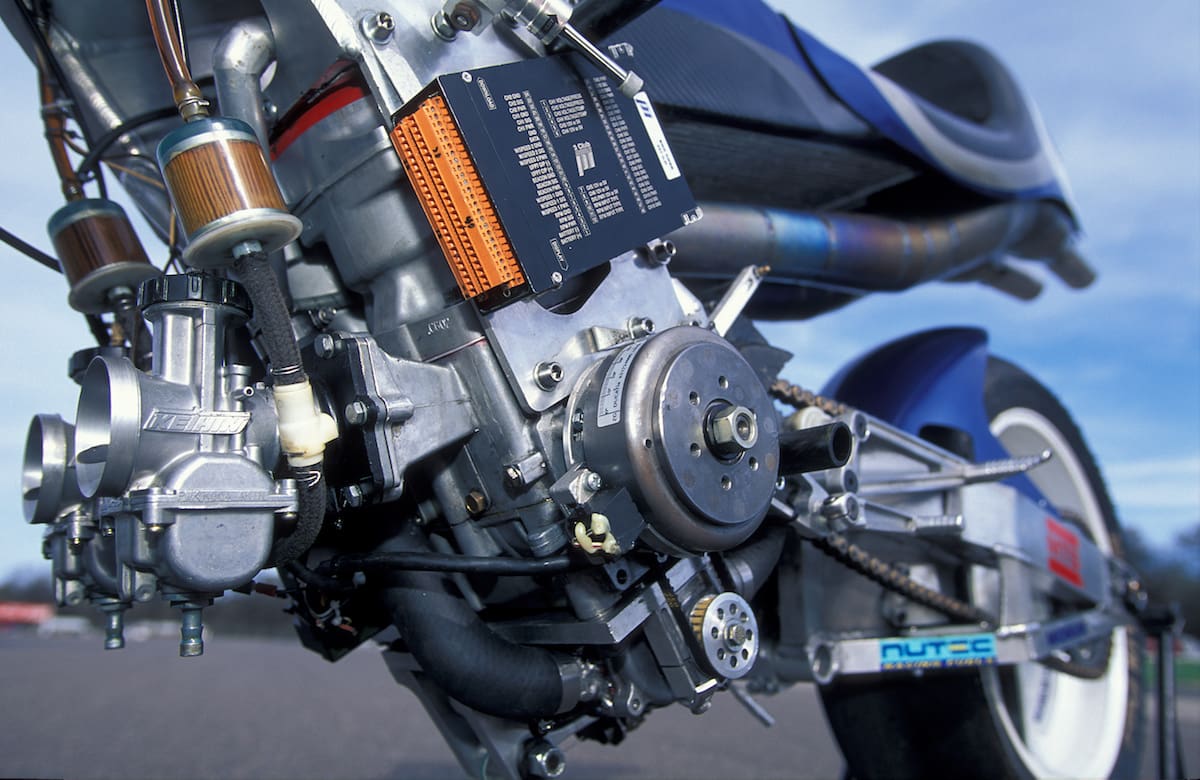

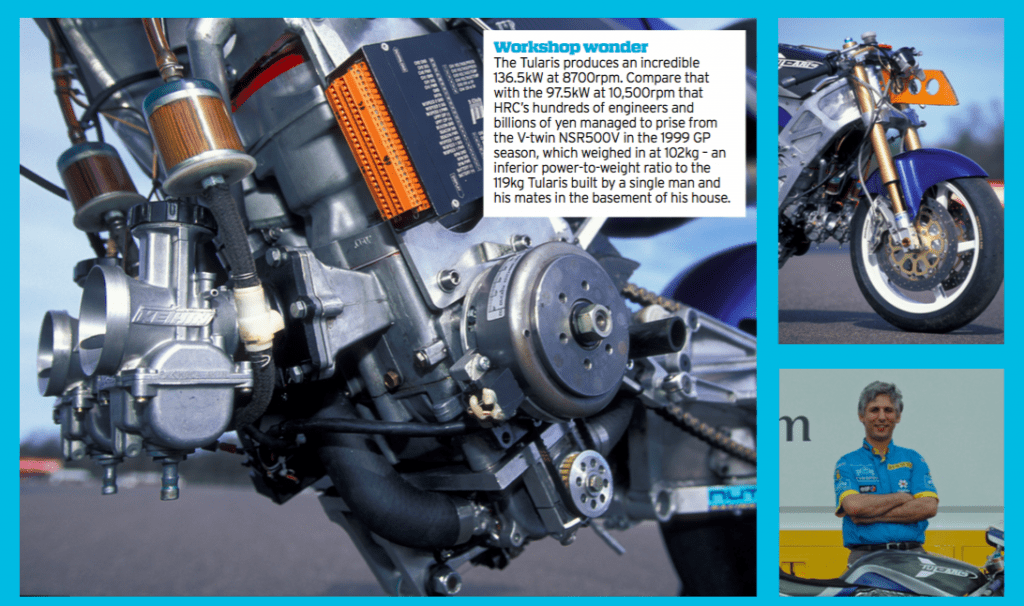

The Polaris water-cooled crankcase reed-valve parallel-twin two-stroke engine with 180º crank (so, one-up, one-down) originally measured 700cc when it left the company’s snowmobile factory in the frozen wasteland of Northern Minnesota, before being pumped out to 85 x 68 mm for 772cc capacity. In this guise it delivered 110kW at the rear wheel fresh out of the basement (123kW at the crank), before Robin later stroked the motor 2mm to 85 x 70 mm for a little more power, but mainly more torque, so that in 792cc form it first delivered 129kW at 8700rpm at the crankshaft – equivalent to 113kW at the rear wheel. But then in the couple of years before he moved to England, and swapped bikes for cars, ongoing development raised that another 7.5kW, allowing Tuluie to ultimately extract 136.5kW at 8700rpm from the minuscule motor, equalling 120kW at the tyre and enough to deliver a Daytona trap speed of 292km/h in March 2003, matched by a hefty 160Nm of torque (at the crankshaft – 141Nm at rear wheel).

My ride came at the Silverstone GP circuit’s test track, between single laps by Renault test driver and 2005 Le Mans 24-Hour victor Oliver Gavin in Alonso’s F1 title-winner, trying to establish a proper pitlane speed limiter program under Tuluie’s direction. Please believe me when I tell you that with its limiter let off, there wasn’t much to choose in acceleration and power-to-weight ratio between the high-tech motor car and the home-built bike. Just lots of money.

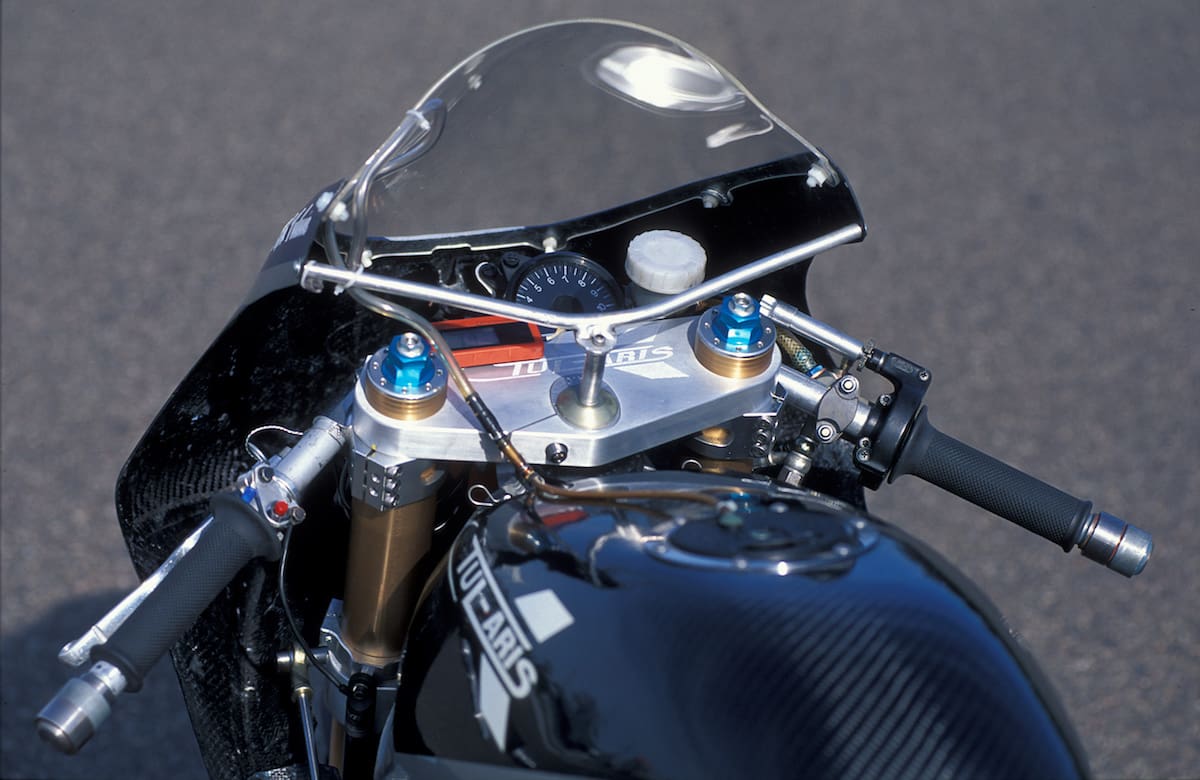

But this was not my first time on the bike. My previous outing had come five years earlier at Brainerd, Minnesota, with its kilometre-long front straight and top gear Turn 1, where World Superbikes first broke the 300km/h speed barrier when they raced there in the 1990s. There, more power was the last thing I was worried about – fewer wheelies were number one on my wish list! That came after I’d tip-toed aboard the ultra-slim but very tall Tularis, and discovered that what seemed to be a minuscule motorcycle when you looked at it was actually surprisingly spacious for a six-foot rider. It’s small, but not tiny, though to tuck properly behind the narrow bodywork, you’d be better off being a pint-sized performer like American rider Michael Barnes. He raced the bike at Daytona for Robin, and declared it to be the hardest accelerating bike of any he’d ever ridden – and that included a V-twin NSR500V Honda, and V-1000 Britten ProTwins racer! It was probably also the most vibrationary at rest. After Robin had started the Tularis for me to warm it up, not only was the sound of the twin-cylinder engine like no other two-stroke I’d ever heard – it’s extremely deep and muscular, a bit like the lumberjacks in Polaris ads! – but the tingles coming through the clip-ons as I blipped the throttle to put heat into the engine were also impossible to overlook. These died away as the revs rose once out on the track, thanks also to the balance weights loaded into the ends of the clip-ons.

In any case there was lots more stuff to get my attention after I’d headed out onto the Brainerd circuit. As you might expect for such a lusty motor, even such a highly-tuned one, the Tularis had a wide spread of power with an ultra-flat torque curve that was also mighty muscular, with reasonable drive from as low as 3000 revs on the Scitsu tacho. You did, however, have to be careful clutching it to coax it back into the powerband like on another two-stroke, else you’d be headed for highside heaven if you were even a little leaned over. That’s because there was a very fierce rush of strong power above 5700 rpm with a step up in power delivery of no less than 37kW over the 500 revs between there and 6200 – an instant hit of horsepower that required you to pay attention. Because of that serious punch of power, you had to be very sure to lift fairly upright before you lit the blue touch paper exiting a turn, to make sure you didn’t get KO’d!

Plus, I needed to be ready to stand on the footrests to try to force the front wheel earthwards as the Tularis wheelied hard, long and high each time I gassed it out of a slow turn, till eventually I got smart and realised that the trick to riding it was to keep the engine revving above 6,000 revs at all times, even if its lusty exhaust note and meaty midrange deluded you into thinking it was okay to surf the torque curve. Once the Tularis got revving above that 6200rpm power threshold down the long Brainerd front straight, it was very, VERY fast – both in terms of acceleration and top speed. It was also encouragingly stable in a straight line, as I discovered drag-racing down that long front straight side by side with a Kawasaki ZX-7RR full-on Superbike. Even hitting the raised ridges of the Minnesota track’s half-mile drag strip didn’t faze the snowmobile-powered racer, in spite of the short wheelbase and tall cee of gee, and it was equally planted round that top-gear Turn 1 right-hander. Robin Tuluie’s mastery of the MTS testing hardware and various computer simulation software, had allowed him to design a really capable chassis package, which steered and stopped well, although you needed to be ready for the back wheel to be lifting under you when squeezing hard from high speed with the six-pot AP front brakes.

The inertia of those big pistons meant that you got a strong sense of them rising and falling beneath you. The Polaris-based engine wasn’t so much a ring-ding two-stroke as a ding-donger – not as fast to pick up revs as a smaller-capacity twin. But the Tularis did pull hard and relatively fast to its 8500 rpm power peak, where it was best to hit a higher gear before making friends with the nine grand rev-limiter. That’s not a thing you normally find on a two-stroke, but those were big pistons, and Tuluie and his engine tuner Steve Houle had obviously figured better safe than sorry, revs-wise. Once I realised I must keep the revs up, that meant using the rather notchy race-pattern gear change to do so, which for some reason didn’t really like shifting up without the clutch – a distinct handicap on a two-stroke.

After grappling with the Tularis that first time at Brainerd, I had three suggestions for Robin about how to make it faster and easier to ride, as well as more effective. First and foremost was provision of a power valve to smooth out that power delivery; next was the wide-open powershifter it lacked coupled with a smoother-action gearshift; and finally a set of shifter lights that lit progressively somewhere above the six-grand mark, then at 8300rpm a bright red junior searchlight to tell you to change up NOW! That would have been helpful to keep the bike revving where its nature said it ought to.

Well, fast forward five years, and at the Silverstone GP circuit I got the second ride Robin had promised me on his self-built creation, but this time on the Evo Tularis, now fitted with power valves! This addition transformed robin’s two-wheeled offspring – it’d still pull mega-wheelies when you wanted it to, only now it was more rideable. In spite of having an even bigger hit of power, it was more forgiving if you didn’t perfectly match revs to throttle openings and gear ratios.

The narrow powerband issue had also been resolved. Now you could use that meaty torque to drive the Tularis hard out of the Silverstone test track’s many slow turns from as low as 3500 rpm, relishing the midrange muscle that was always there before, but which you couldn’t access properly because of the layered power delivery and constant wheelies. This 5200 rpm powerband – almost two-thirds of the engine’s entire rev range – in turn meant you could save gear changes by holding a gear from way low to way high, without having to worry about fighting the front wheel to make it stay on the ground when you passed through the 5700 rpm power threshold. Much better, Robin – take a commendation for your homework!

But apart from occasional demo outings at high-profile events like the Goodwood Festival of Speed (where Robin rode it in 2015), it’s a sad fact that one of the most innovative and improbable motorcycles ever built now sits tucked up in its snug retirement home beside the river in rural England. Let’s leave the last word to Robin Tuluie, its cerebral creator, who will probably still be bringing up baby a decade from now – just look how many times Michelangelo went back to touch up the Sistine Chapel!

“The nice thing about building this bike was the fun I had developing it, and the people I met doing so,” he says. “I’ve made friends for life thanks to the Tularis, and that’s the best thing about it for me – that and beating the Suzukis to win that Formula USA race!” And good practice for being part of the team which brought both Renault and Mercedes-Benz from being perennial non-achievers in the maelstrom of Formula 1 racing, to becoming dominant world champions.

TEST ALAN CATHCART PHOTOGRAPHY JÜRGEN GASSEBNER & LAURIE CADDELL