It seemed a lifetime since we’d stood in Montenegro on the Balkans ride looking out over Lake Ohrid and quizzing our old mate Cristian about the mountains to the south.

“That’s Albania,” he told us. “I’ve been thinking about a ride through those mountains soon, just to check out accommodation.” The six of us signed on immediately as, while we’d become familiar with much of the Ionian coastline, Albania remained a mystery.

Now, after a few false starts and three years of Covid disruptions later, here we were in Athens looking at a brace of near-new 2023 BMW R 1250 GS Trophys, plus an F 750 GS for Ray whose fused ankle is not compatible with the layout of a boxer engine. Athens was chosen because of the shortest flight time from Australia and being not too inconvenient for Cristian to truck the bikes from his Moto Hub base in Bucharest. On previous rides through Eastern Europe we’d elected to go with hard panniers and top boxes, but with the Moto Hub van already in Athens the option of riding without any encumbrance was a blessing.

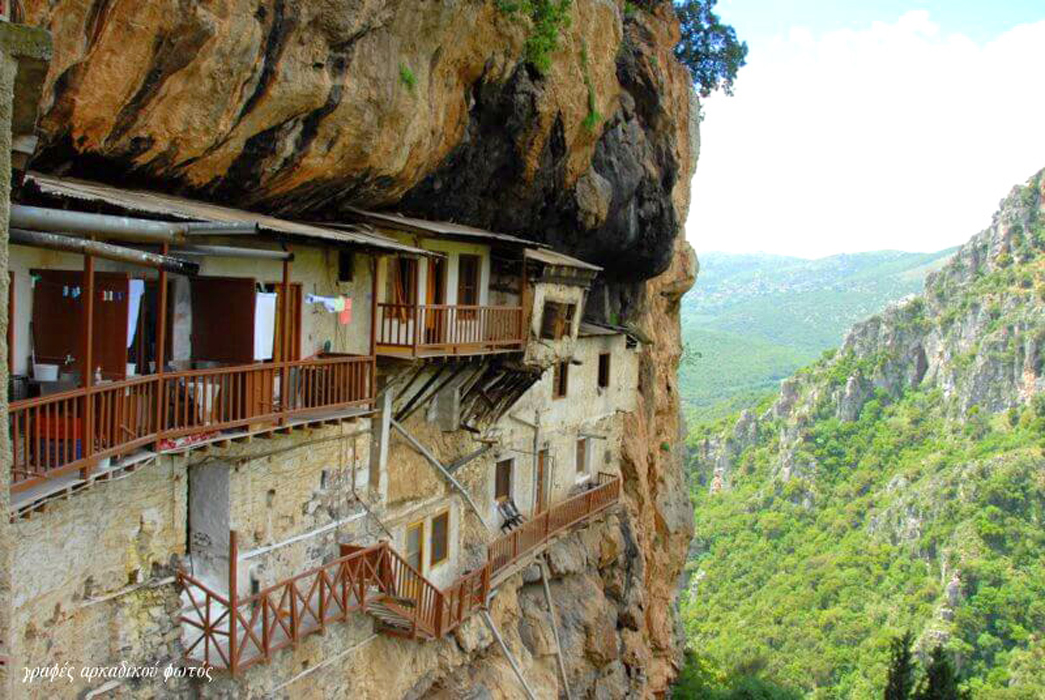

Less than an hour on the motorway west of Athens, the Corinth Canal linking the Corinthian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea, effectively makes the Peloponnese Peninsula the largest of the Greek Islands. Home of legendary archaeological sites such as Messini and Sparta, more than 300 one-goat villages, plus monuments, missions and monasteries on every mountain below the cloud cover, much of the peninsula is a traffic-free zone. The major centres are now serviced by a six-lane tollway, the numerous secondary roads that rise from sea level to more than 1200m and back again in less than 100km now provide seldom-used access to long abandoned hamlets.

Most of these roads are rated as very narrow, scenic routes. This indicates that, with care, two Toyota Corollas can pass without clipping mirrors. These traverse across the Targetos, Minthi and Páronas mountain ranges and were hacked out of the cliffs by goat herders back in the Bronze Age. And while tarmac has since been laid over the crushed limestone, further maintenance was deemed superfluous. And as the many signs warn, rocks will fall before your very eyes.

That experience was still to come as our first 350km day wound south along the coast of the peninsula, overlooking the Saronic Islands to the east with the 2000m peaks of the Párnones mountains to the west. Attractions included the world heritage-listed Epidaurus Theatre and Sanctuary of Asclepius, plus the picturesque villages of Astros, Lionidio and Skala.

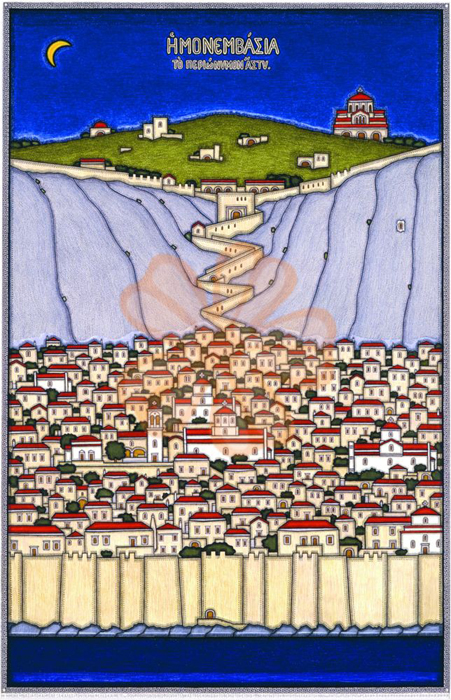

Cristian well knew that by avoiding the main highways and the huge industrial complexes that produced the mountains of cement required for the extensive motorway network, everything else could be described as attractive, scenic, picturesque, panoramic, quaint and/or delightful. Nothing more so than our first night’s digs in Monemvasia: a medieval fortress hanging off an isthmus in the Minoan Sea with a great selection of tavernas serving the local brew ‘Sparta.’

There were sufficient tractors, overloaded utes and disoriented goats to hold everyone’s attention through the orange, lemon and olive orchards that kicked off day two, but the locals were very aware, allowing the bikes plenty of room on the narrow roads. Bypassing Sparta we headed west on what was designated Route 82 across the 1300m Langada-Täygetos Pass – only 61km according to Google, but in the mist, drizzle or fog well over an hour’s ride with lots of short unlit tunnels carved into the cliff face; far, far too many overhangs and rocks on the road.

In such conditions, thinking what could be, and hoping it’s not, there’s always a bit of hesitant braking before the next bend – the bitumen barely 3m wide in places. Then a road closure sent us off on a long, very narrow unmapped diversion – though it was obvious from Cristian’s confidence that the detour was familiar. West of the mountains, the weather cleared for a quick ride up National Route E55 to Olympia and the Europa Resort. It was warm and the swimming pool looked inviting, though the cold bottles of ‘Mythos’ from the pool bar won the day.

Iraq may well have been the cradle of civilisation, however archaeologists agree that Greece was the nursery. Between wars, the Greeks have a history of over 3000 years of goat herding, olive growing and project building behind them. Over 16,000 tourists visit the Acropolis every day, and soon it may be by appointment only. Ancient Olympia may be next: a comprehensive, well-signposted excavation with a museum that’s far easier to navigate than its counterpart in Athens. It was a personal highlight, followed by an outstanding meal at Taverna Orestis.

Our itinerary took us north on Route 33 to Patra, across the 3km Rio-Antirrio Bridge that connects the peninsula to mainland Greece, then through the 3km tunnel under the Náfpaktias mountains, to the coastal foothills and across a causeway to Lafkada Island. According to Odysseus, it was here Sapho committed suicide and Artemisia of Caria also jumped to her death from the cliffs. Now the town centre is a modern, 1000-acre (400ha) marina encircled by a vast al fresco restaurant – at which we were the only patrons, feeling obliged to keep the waitress busy. Yachties, windsurfers, snorkellers and sailboarders would love Lefkada but we were anticipating the ride into Albania.

Approaching isolated border crossings, the signs for customs and immigration can create a touch of angst, but for Aussies Albania is a visa-free destination and Cristian had already distributed the necessary paperwork for the Beemers to get through. With no hassles at all, we were soon aboard the old cable-driven punt to the ancient fortified town of Butrint on the southernmost tip of Albania.

Butrint is a site which, according to the world’s leading archaeologists, has been occupied since 50,000 BC. Over the centuries, control has been disputed by the Greeks, Persians, Macedonians and Romans – only the Mongolians didn’t have a go. This argy-bargy continued right through the last two world wars and it wasn’t until 1959 that Nikita Krushchev ratified Albania’s sovereignty.

Since then Albania had been in the naughty corner for drug trafficking; the mountain region south of Gjirokastër alleged to be the cannabis capital of Europe. Now it’s reported the Albanians still control the market but the crops are produced in vast underground farms located in northern Scotland, making it possible to ride without stress in remote areas without upsetting shotgun-toting farmers.

Arriving in Sarandë from the south, passing scores of construction sites, it was evident why the region was already being referred to as the Albanian riviera. Not surprising then, that the more established end of town was almost a replica of Monte Carlo in the 1970s. No royal palace and (as yet) no Formula 1 circuit, but a kaleidoscope of multi-tiered high-rises from the skyline to the waterfront – including our digs in the Demi Hotel.

It’s rumoured Sarandë’s development boom is largely funded by the Russians and, while we didn’t spot any obvious oligarchs, there were a number of butch blokes in tight black t-shirts lurking about. Sarandë is connected by ferry to nearby Corfu, one of the more popular Greek islands, however after a walk around the harbour it was time to assess the local brews. The aptly named ‘Korka’ won hands down and, while we relaxed, Cristian spent much of the day sussing out some roads that were under construction when he was last in the country.

Our next overnight in the walled city of Gjirokastër was, as the crow flies, only 25km from Sarandë. However, to cross the Maja a Këndoricës – the highest road on this ride – we had to travel 250km north along the Ionian coastline before turning east across the mountains.

Such is the rapid development in Albania, construction of the motorway from the capital Tirana to Sarandë is a major disruption – which we avoided by heading inland to Mavrove. Somewhere along here, Cristian spotted an unsigned eatery which may or may not have been open for business. The operators didn’t speak Romanian, Cristian didn’t speak Albanian and my Tasmanian didn’t help. There was a goat on a spit in the smokehouse which may or may not have been ready for lunch (it was a little tough and underdone), though with some salad and bread it managed to fit the bill. As it transpired this was the only civilisation we encountered in the next two hours.

From that point, somewhere around Vajzë, the road was still under construction. Sort of. The new blue-metal surface was perfect, except for the construction debris. It appeared as though, having completed the road project, the crew had just up and left. Despite the 200m or more drops, there was no Armco, no road markings and no advisory speed signs. Very, very fortunately there was no traffic.

Getting to our hotel in Gjirokastër, through a maze of steep cobblestone lanes, some of which required a three-point turn on the Beemers, proved a challenge. Overnight rain caused some real apprehension about descending through the village on wet cobblestones, but everyone survived without incident and soon we were crossing the border back in to Greece.

Still to come was a long scenic loop through the much photographed mountain-top monasteries of Metéora – most comfortably viewed from the hotel balcony. Then past Thermopýlae, where 300 Spartans held off 14,000 Persians. It makes it easy to comprehend why the most popular beer in Greece is ‘Mythos’ – the maker of myths.

Our second last night was in Delphi, the Pan-Hellenic sanctuary of Apollo, Olympic God of light, knowledge and harmony. As impressive as all these historic remnants are, there was no comparison to the ever unfolding views, on each and every day. The 1700m pass north of Amfissa or the spectacular arid scenery along the 100km byway north of the Corinthian Gulf between Itea and Thiva completed the journey back to Athens. All told, we travelled less than 2000km over eight days on the move within a footprint the size of Victoria. Few countries offer such extensive diversity in such a small area. The world famous statuary and artefacts are a bonus.

Words + Photography Peter Whitaker