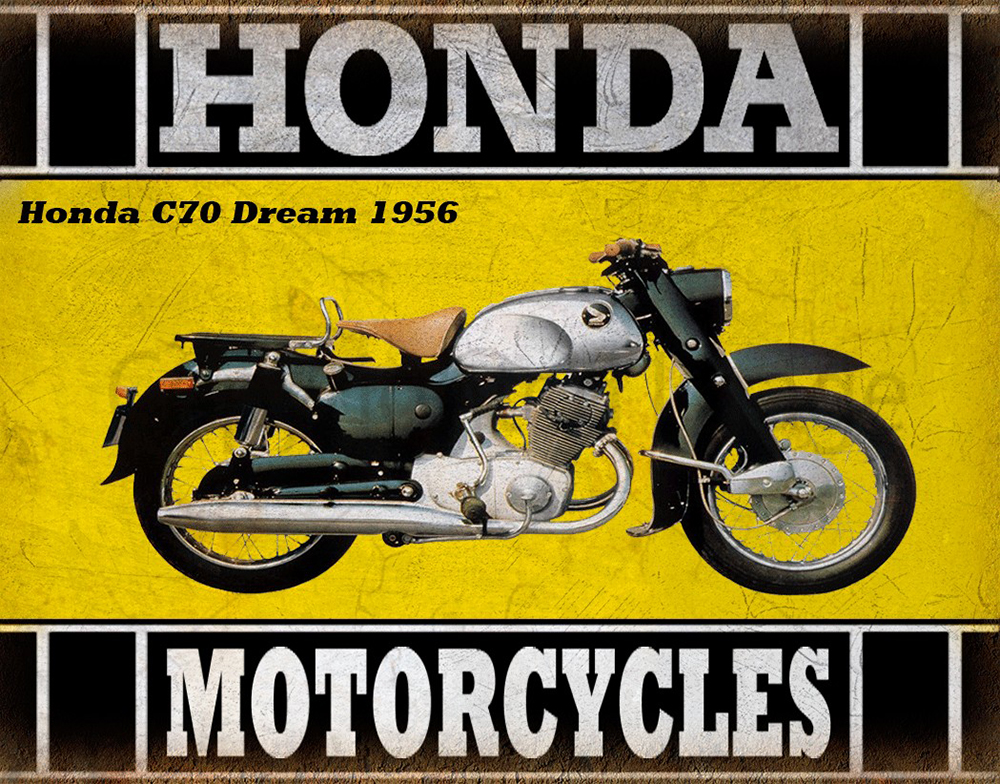

The first Honda Dream hit the showroom floor in 1957 when B&W took on the Australian distributorship. Shortly after, our local Lions Club held the Ryde Motor Show as a fund raiser. Ryde Motorcycles’ display included a 175cc four-stroke Moto Guzzi Lodola, a 200cc two-stroke Zundapp Bella, a new Tiger 110 Triumph, a 600cc OHV Norton, and a bright red 1958 C71 Honda Dream.

The Dream was allocated pride of place and I enjoyed the startled looks of the passing peasantry as I plied the electric starter then, as an encore, flicked blinkers on and off. Even though I had no idea of the price, there were people eager to put up a 10 pound holding deposit. The six Hondas for which I took these deposits were likely the first to be sold anywhere outside of Japan.

After the show, in order to examine the unusual, pressed metal, box-section frame, we removed the fuel tank, only to be horrified at the hand-beaten underside of the tank on which, under a thin coat of paint could be seen: C.C Wakefield CASTROL. Many people have since told me this is an urban myth, however I assure doubters I removed the tank myself and saw the underside with my own eyes.

Was this an early prototype which had slipped un-noticed in that first shipment from the factory? Or could Honda be using crate-loads of old Castrol oil tins in the base of its well sculpted fuel tank? Certainly the welding on many frame pressings and pipe tube ends left a great deal to be desired. Yet it has to be said those early Honda engines idled like Swiss watches; though some cynics suggested you could hear them wearing out by the sound of the overhead cam drive-chain and valve gear.

Head-on, the Honda Dream was pyramid shaped, the fat mufflers sweeping outboard of the ultra-wide crankcases, and the footrest hangers, rear brake pedal and centre-stand arm outboard of that. Adding to the appearance were tiny 16-inch wheels, which allowed minimal cornering clearance.

So you couldn’t corner quickly but you could pull up to the gutter and use the left muffler as a prop stand. In fact, if the bike were cranked over a few degrees from the vertical when riding, the mufflers would dig in to the road surface with great enthusiasm. To make matters worse, the springs contained within the leading-link forks on the front and oblong shaped shocks on the rear, were bereft of any form of effective damping.

The so-called rotary gear-change was a trick in itself. You would push the pedal down from neutral to select first, down again for second, again for third and again for top. More often you’d hit a false neutral. Then, and this is the trickiest part of all, if in the confusion at apparently missing a gear, you pushed the pedal down again, you’d find first, lock the back wheel, spit sideways, snap at least one of the chain adjusters and end up over the handlebars!

This happened so many times that, if the rider of a brand-new Dream entered your spare parts department on tip-toe, eyes agleam with tears and bottom lip sucked in, you would reach under the counter and present him with two new rear chain adjusters. The ratio as, I remember, was two sets of chain adjusters to one crankshaft which, on the second occasion the rider sailed over the bars, would snap like a carrot.

Honda improved, the Hawk appearing just a few years later with a more acceptable semi-tubular frame, telescopic forks and twin-leading shoe brakes. The clutch had by then been moved to its rightful place on the gearbox main-shaft and the shocking rotary gear-change had disappeared.

The Honda Hawk was a first rate motorcycle, which proved beyond question Honda had learnt very quickly indeed.

This is an edited extract from Lester’s memoir Vintage Morris