Don Cox tells us about the making of Circus Life, a publication about Australian motorcycle racers in Europe in the 1950s.

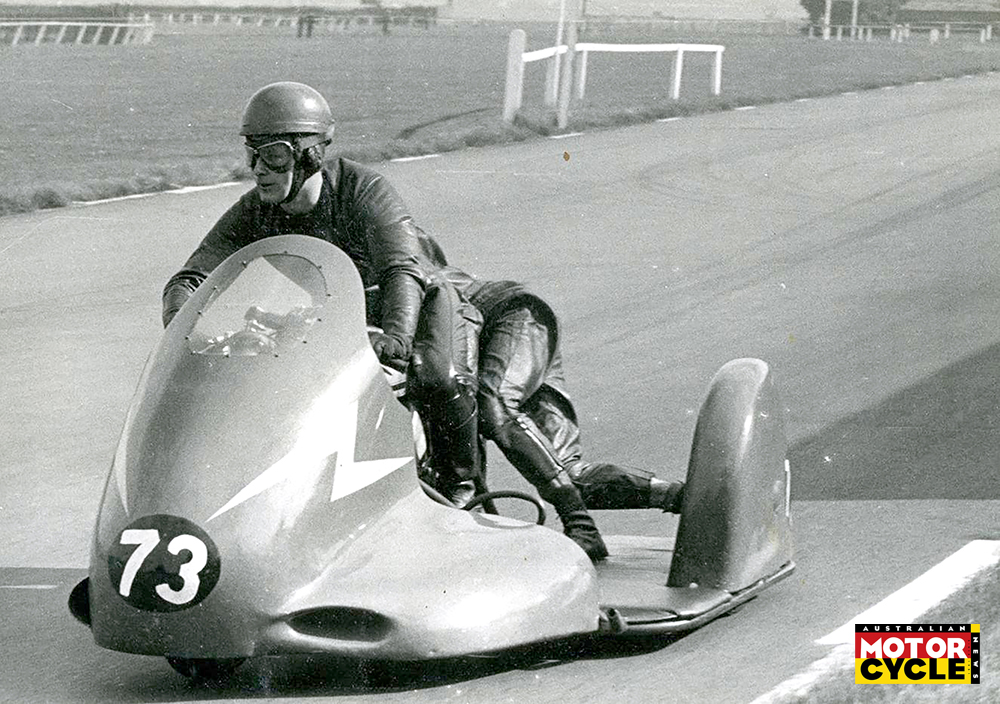

Leaning out of a racing sidecar outfit, left shoulder six centimetres above the tarmac at 160km/h, wasn’t how dress-cutter Jean Kilpatrick saw her future when she left Melbourne with racer boyfriend Ray Foster late in 1958. Nor was living on packet soup when funds were tight at race meetings. But Jean’s willingness to “try anything” made her Australia’s first female competitor in motorcycle Grand Prix racing, a role she filled for four years.

Jean’s unique experience was indicative of what you may unearth when you search outside the square and listen to Australian private entrants of the day. Similarly, visiting a then 85-years old Jack Ahearn at home in Lismore and quoting his contemporaries, who reckoned they knew when he was poised for a ‘big’ ride, because he would sit and stare at his bike for ages. The arch privateer roared with laughter at this suggestion.

“No, I kept racing on the Continental Circus because it beat working for a living!”

It is 10 years since Circus Life, Australian Motorcycle Racers in Europe in the 1950s was published. Earlier this year, Mike Nicks, former editor of Bike magazine in the UK, read the book and said it would be worth telling how those interviews came about and how the book was compiled.

So here goes! It began with the thought of doing more on the 1950s’ Australian private entrants’ story and their peripatetic lifestyle, a topic Will Hagon and I explored in Australian Motorcycle Heroes in 1989.

One idea, to do it as part non-fiction/part imagined, was soon ditched. The truth was way better than fiction. A novelist would struggle to invent characters like Ahearn or Tony McAlpine. Idea two was to focus on six or eight key players from the era. Fellow magazine columnist Jamie McIlwraith read my draft introduction and said if you’re going to do this, you need to cover everyone.

That’s a big cast and, sadly, 10 Australian riders who were part of the Continental Circus in the 1950s did not make it home to tell their stories. Others settled overseas, lost contact with the motorcycle scene (including Ray Foster) or not lived far into the third millennium.

So you take a punt tracing potential contacts, including surviving journalists, parents, partners, in-laws, rivals and former mechanics/travelling mates through chance findings, hunches and old-fashioned shoe-leather journalism. Keep listening, keep asking questions and sometimes you strike gold. Once you find a couple of these people, they lead you to others.

They may provide information on a racer’s daily life, misadventures or what it was like behind the Iron Curtain in an era when a mere handful of Australians had ventured there. They could describe the humorous side or even acts of bastardy. Some kept a diary or retrieved the letters they wrote home. A bare-bones racer or wife’s journal can still reveal events between race meetings, van breakdowns, dalliances, social activities such as a sailing on a lake near Assen and additional prizes given by town business people for a combative ride.

An example of a chance finding: Cadours in southern France, June 14, 2006. Hunting for the nearby public-road circuit. It’s blazing hot and the village is closed for lunch – except the local bar, which is dark and cool.

A copy of the Moto Revue 1958 Cadours international race report brings an instant response from the barman. He may be younger than the magazine, but the moment he sees its shock headline regarding Australia’s Keith Campbell, he knows its significance and nods toward a man seated at the back watching horse racing on television: “Roger saw that accident!” he says.

Another example, in this case a tip from Bob Edmonds, who was Keith Campbell’s helper in 1955. Bob talked of Sydney women Margot and Dorothy who headed off on a Grand Tour of Europe and found themselves travelling with Isle of Man TT official rep Bob Brown for a few months. Margot married works Moto Guzzi rider Duilio Agostini.

Agostini (no relation to Giacomo) opened a motorcycle shop by Lake Como in Mandello del Lario in the mid-1950s. He had passed but the shop still carried his name and had become a must-visit for Australian Guzzi enthusiasts. Duilio and Margot’s elder daughter Alis was still involved, so I sent an email.

Next day came a reply to the effect that: “Mum is visiting Sydney at the moment and here’s the phone number where she is staying.” Margot had stories and photos from her travels with Brown, from jumping off the bus at hairpin bends on mountain passes to fetch more water for the radiator to using a fuel clothes iron. It frightened her to light it, but “we took pride in our appearance”.

Another amazing back story came from Warrnambool carpenter turned racer Neil Tinker. Elder brother Len Tinker suggested they needed a serious injection of funds to keep racing in Europe, so Neil spent ten months working above the Arctic Circle in Canada, building early warning radar stations for the US Air Force.

Len had passed, but word had it Neil was in Canada, so time try the Warnambool telephone listings. The first Tinker who answered was indeed a cousin. “Yes, he’s in Canada, I’ll find a number for you.”

Neil was a great source. He had a host of memories on the 125 and 250 MVs the brothers bought and guys they travelled with. He said the factory mechanics resented the brothers having MVs and would never share tuning tips.

George Scott, the only West Australian selected in Australia’s official TT team, had passed. However, Perth’s Ken Duperouzel knew his story and had a scrapbook of his 1953 season. Scott was one of several 1950s Antipodean internationals who sailed away with a new bride. For one season he lived the great adventure, seeing new lands and being paid to participate in his favourite sport.

Roger Barker was a radio announcer from Mudgee, NSW, who earned selection in Australia’s 1957 TT team. Sadly, he died in a race crash at Schleiz in in East Germany within months of joining the tour. Relative Tony Jarrett from Toowoomba in Queensland arranged for a meeting near Coffs Harbour with Joan Barker, widow of Roger’s late brother Aub. Joan had the details of Roger’s domestic and brief international career. Aub and Joan had visited Schleiz. That was a story in itself, with the East Germans denying access on their first trip.

Mildura, Victoria, resident Ron Day had the inside story on hanging out with Moto Guzzi riders Dickie Dale and Bill Lomas in his home town, Dale meeting a local nurse and subsequently having to pay £3000 for breach of promise to his English fiancée, travels in Europe with Keith and Gwen Bryen, and accompanying Keith Campbell on his career-changing trip to the 1956 Swedish TT.

Hansjőrg Meister created the website Feldbergrennen.de to tell the story of the international races in his home town in the Black Forest region. His family billeted Australian riders and made sausages to sell to spectators. He confirmed the story of Jack Ahearn taking a dunking in a large rain puddle at the finish of the 1954 500 race to beat compatriot Maurie Quincey. It was a miserably wet day with only 30,000 attendees. Ahearn was so determined to prove a point to Quincey he did not back off for the water! As a post script, the organisers lost money and the meeting was never held again.

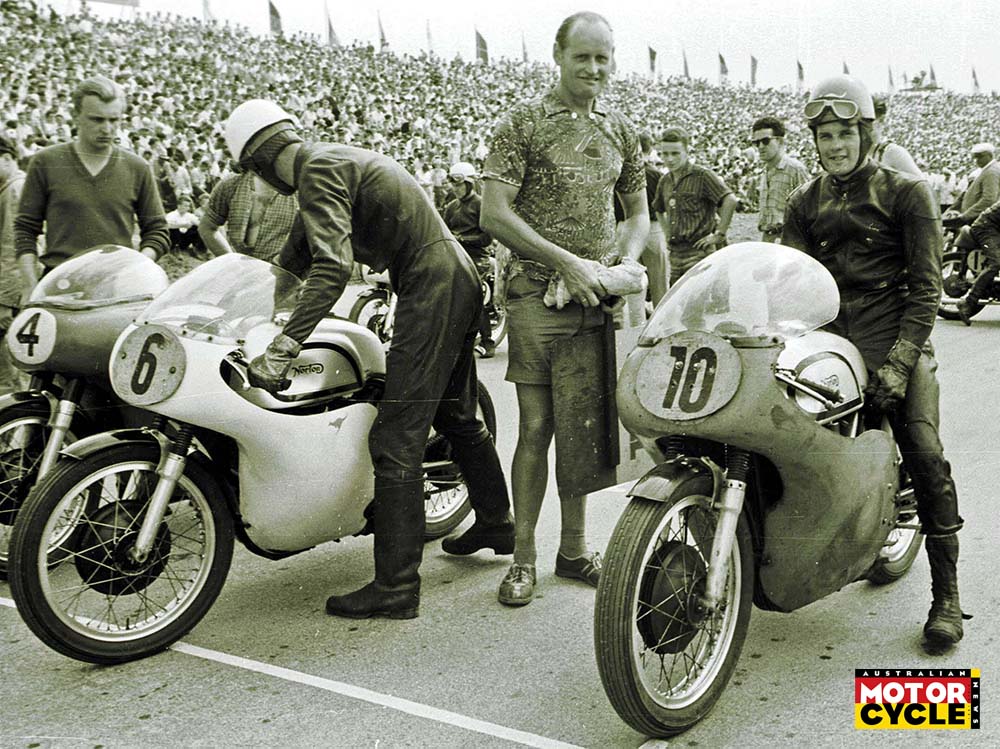

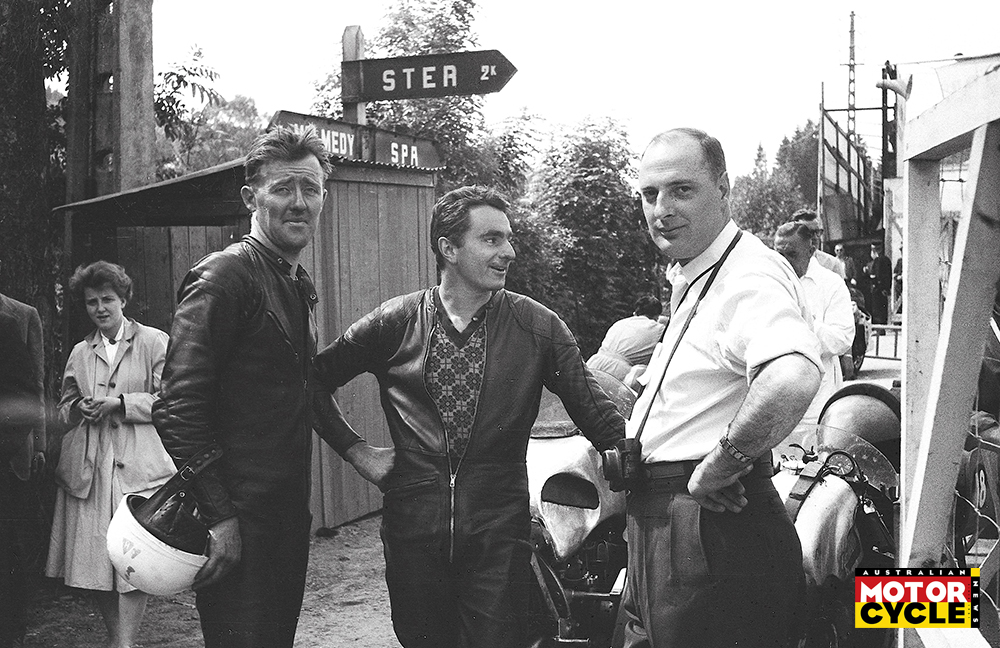

Lanky Melburnian Bob West talked of his 1960 season travelling Europe with a then little-known Jack Findlay, with four Manx Nortons in their van. His key insight came after making an unscheduled pit stop in the 1960 Belgian 500 GP at Spa-Francorchamps, putting him a lap behind Bob Brown and other aces. He watched them drift their Nortons and appreciated immediately how hard they rode. Drift a 50 horsepower Norton? You could on the hard, narrow tyres of the day.

Collecting the racer stories is, of course, only part of the process. You need photographs and you’d prefer shots that have never been published. That opened a new research avenue, corresponding with locals who had seen the Australians race. People who as school children were thrilled once a year to see the racers come to their town.

Typically, they attended the races with their father and had recently posted his photographs on the net. Some offer those photos for sale, others are happy to share and provide detailed accounts of how a town of perhaps 12,000 people united to stage a race meeting attracting 60,000 visitors, as well as a prize-giving function featuring national celebrities. A few went on to create a website, book or video on their local race meeting.

They could recount the excitement of obtaining their favourite visitor’s autograph, their family billeting or renting their garage to an international racer or simply travelling to the race.

Bernd Bouillon was an eight-year-old coal miner’s son in St Wendel, the Saarland, when he approached Tom Phillis, nervously clutching an autograph book. As a little boy, he reckoned Tom might as well have come from the moon as the other side of the world. Bouillon, who died in October 2021, was a Phillis’ fan from first time he saw him ride in 1958. As an adult, he made a pilgrimage to the Isle of Man to visit the site of his fatal accident and did German-language commentary at the TT.

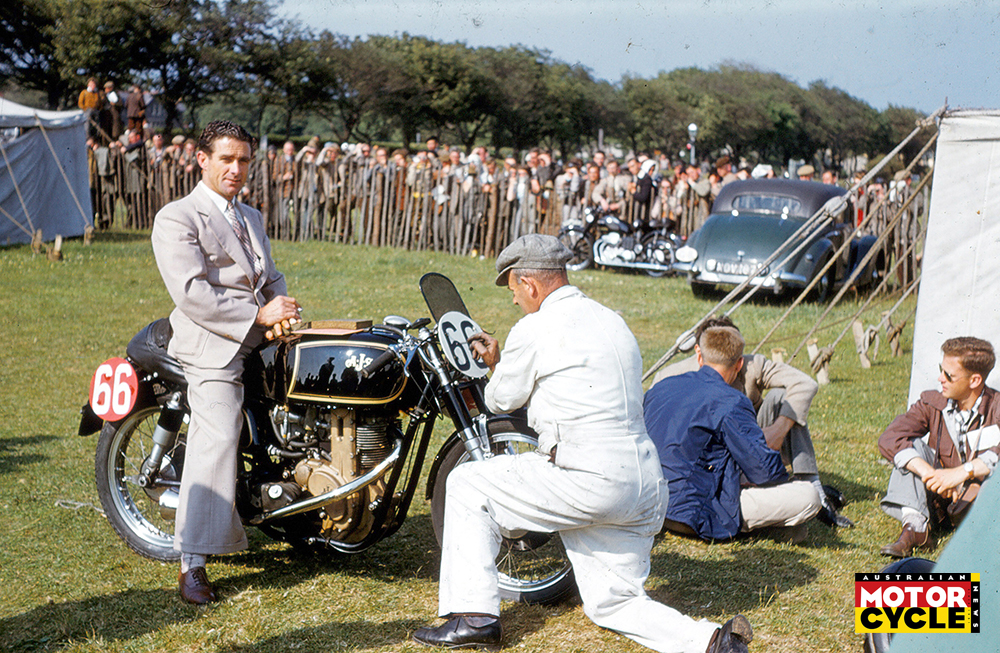

Speaking of photos, a couple of Australian adventurers either bought or were gifted their first 35mm camera as Circus rookies. Keith Bryen shot extensively in 35mm colour. When he was on his bikes, wife Gwen would do starting-grid photos. Their daughter Stephanie became a photographer.

Bob Edmonds was best mates with Keith’s elder brother George. He chose to go with Keith when the pharmaceutical company he worked for wanted to post him interstate. Bob concentrated on 35mm black-and-white photos and wrote superbly detailed letters to his sister in Melbourne.

He helped garner support among riders for the Dutch TT Riders’ Strike, which saw many private entrants withdraw after one lap of the 350 TT in protest at abysmal starting money. And he accompanied Campbell on his winning trip to the Czechoslovakian GP at Brno in August 1955. Figuring letters would probably be steamed open, he waited until he was back in the West to provide a candid assessment of life under Russian domination.

Edmonds’s trip had a brief but lucrative sideline. He took his stove-hot Matchless clubman racer on the ship for £5 as passenger’s luggage. Matchless was an unfashionable brand at the time. Bob took a month off from helping Campbell to visit the Isle of Man and England. He delighted in winning unofficial sprint races against guys on the latest 500 sports machines.

Photos from motorcycle newspapers and town photographers also feature heavily in the book, shots often given to racers. Starting-grid photos are especially handy, showing who was at the race and giving clues on the circuit location. The local tourist office or library can usually identify the street.

Sometimes it is the things people do not tell you or one photograph that can change your perception of events. Two hours north-east of Cadours is Villefranche-de-Rouergue, which also hosted an international race in the 1950s. Keith Bryen and Eric Hinton both have starting-grid photos from 1956. Standing where those photos were taken, you cannot miss something the two racers never mentioned. You’re literally in the shadows of a magnificent cathedral, La Collégiale Notre-Dame.

For a racer, there’s no time to be distracted by a 13th century church. Especially when, as the photo shows Hinton doing, you’re not looking at the starter. He’s looking across the grid, watching for French ace Pierre Monneret to heave his Gilera forward. That’s when the race will start – on a sly signal from the man with the tri-colour.

More priceless photos appeared over time. Sidecar ace Bob Mitchell literally found negatives in jam tins at his Southport home. The Drenthe Archive holds negatives from the history of the Assen region, from agriculture and transport to the motorcycle racing, and sells electronic copies. An English collector who bought a German collection of 1950s grid shots and needed assistance identifying them, in return for limited use. Working on magazines and bike newspapers had taught me to pay attention to photo captions, as they’re the first things many people read.

But how do you make a book happen when publishing houses consider it too large and too niche? You self-publish. The late car historian Graham Howard was a fabulous help, from suggesting a print contact to reading and commenting on the first draft.

Sadly, Graham became seriously ill with cancer at that point, so current and former colleagues were involved in the sub-editing. Alan McArthur did the book design. With an overview section, separate chapters on 17 riders and combined chapters featuring many more, it would be a large book, so we sought to maximise quality. Fortunately, a publisher in Brisbane had told me about 1010 Printing and its Australian office staff had great suggestions to achieve that, right down to ensuring the dust jacket would resist tearing.

It is something to send off electronic files for a 480-page book and receive two air-freighted proof copies. And two months later to be advised that more than three tonnes of books have arrived at Port Botany – please ensure the delivery point has a forklift. Initial distribution was via a mailing house suggested by photographic book producer and AMCN contributor Phil Aynsley.

Norton machines figured so heavily in the story of 1950s road racing that the book launch was held in a bookshop in Norton Street Leichhardt. Key characters and sources including Keith Bryen, Eric Hinton, Betty Phillis, Bob Mitchell widow Jean and son Mark attended. Seventies racer Mick Cochrane drove Keith Bryen from the Central Coast for the event. He was enthralled, listening to Keith talk about his Continental Circus days and riding for Moto Guzzi. There was a second launch in Melbourne in 2013.

In the years since, the specialist book sales scene has changed dramatically. A bricks and mortar outlet in Perth that sold many copies no longer exists.

Sydney only has one specialist motoring/motorcycle book shop. Conversely the book sold well in the UK, especially Northern Ireland, where the lure of public-road racing remains strong.

There are many more sources to mention. They are in the book’s acknowledgments. And other great times tracing the stories. Who would not be entertained with Jack Ahearn venting on tight-fisted race organisers?

However, Eric Hinton talked of St Wendel race director August Balthasar making every effort for visitors, from piloting them flat-out around the circuit, hosting them to dinner and providing extra prizes for spirited rides. He told Eric he “liked his Australian cowboys.”

Looping back to Jean and her sidecar days, one of the best was Easter Monday 2010 in Melbourne talking Jean Foster and the same day with Dawn Johnston about life on the road with her late husband Neal and their son Peter. Extraordinary women with fascinating stories. It was a privilege to gather and recount them.

(Circus Life is available through Amazon and other retailers. More information is available here)