Alongside his colleague Fred MacSorley, John Hinds, became famous as one of the Flying Doctors. Mounted on motorcycles and carrying bright orange packs stuffed with medical equipment, the pair provided the fastest medical response in world motorsport, saving countless lives at Irish bike races over the past decade. But tragically, the 35-year-old John was tracking a group of riders during a practice session at the Skerries 100 on 4 July this year when he inexplicably crashed his S1000RR BMW and sustained fatal injuries.

The death of the man who had watched over everyone else in the high-risk business of racing on closed public roads stunned the bike racing paddock and left his family and friends devastated.

“John always believed there was something that he could do to save lives.” his partner, Janet says as she sits in the couple’s living room surrounded by pictures of herself as half of a happy couple that no longer exists. “He realised that using the bike he could get to the scene of a crash much faster. Those first few seconds are vital in not only ensuring someone survives but also in making sure they survive intact.

“Of course he got to indulge his passion for riding bikes too! John adored being on the bike and he wouldn’t have been able to do the work he did if he hadn’t.”

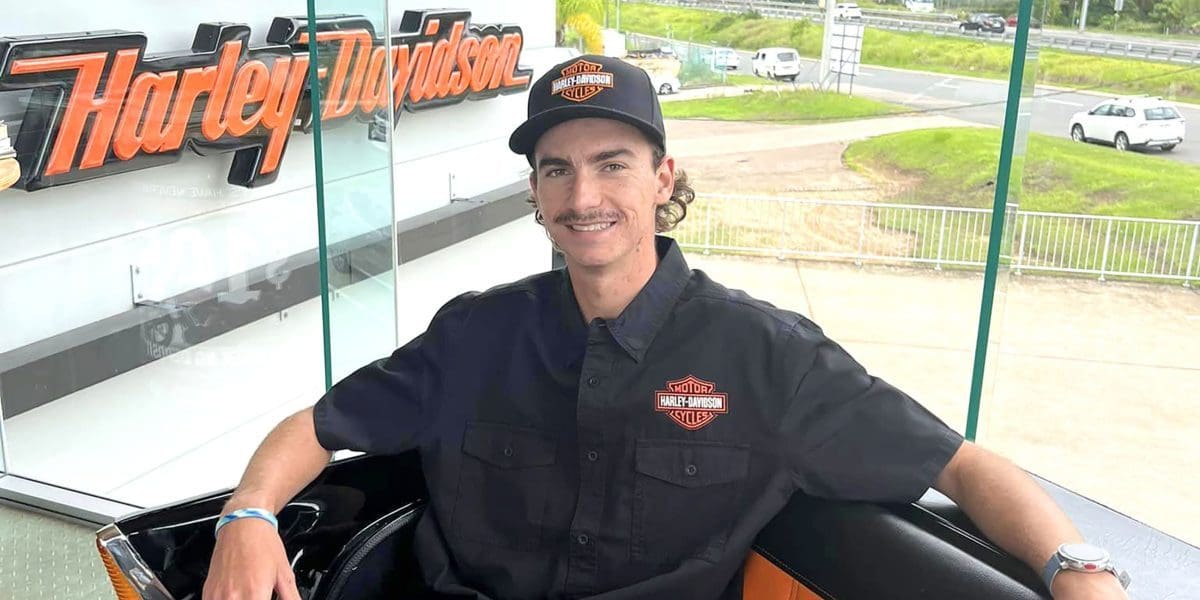

PICTURE BY STEPHEN DAVISON

Unusually in Ireland, no one in John’s family was interested in motorbikes. But as they lived close to Kirkistown, one of Northern Ireland’s short circuit tracks, he became curious about what went on there.

After watching his first track races at about 14 or 15, John went to the Ulster Grand Prix at Dundrod and was immediately smitten by the spectacle of road racing. At the age of 17 he acquired his first road bike, a Suzuki RG125. And when he later enrolled in medical school, he had the opportunity to dovetail his twin loves of medicine and biking. John explained the route he took in an interview he gave me shortly before his death.

“It isn’t until your third year of medical training that you actually meet any patients and it is usually in a clinic or GP’s surgery.” he said. “My first patients were road racers.”

John signed up as a member of the Motorcycle Union of Ireland of Ireland Medical team. Using a van and medical cars loaded with resuscitation equipment, the squad of doctors and paramedics – all full-time medical professionals – provide their services at races as unpaid volunteers.

Initially, John observed the squad in action before being allowed to go hands on himself.

“You have to familiarise yourself with how racing works, how the sport and its environment operates, or you are of no use to anyone.” he explained. “You need to know things like the way a two stroke goes silent when you shut the throttle, or you could be running out in front of bikes that are still racing. You learn those things and how to fit into the team during your two-year apprenticeship.”

The apprenticeship also involved honing his riding skills.

“Fred and John loved riding their bikes and they went to Jerez and Almeria in Spain during the winter with (former North West and British championship race winner) Woolsey Coulter for coaching sessions.” Janet recalls. “I even bought him track days at Mallory Park as a birthday present. It was really important to him that I enjoyed the bike too and I rode pillion with him, getting my knee down a couple of times!”

Fun as his biking was, it was also a crucial part of John’s race-day job as neither Fred nor him could risk getting caught by the likes of Michael Dunlop or Guy Martin as they followed on the opening lap.

“His riding skills were extremely important to him and John would never put anyone else at risk.” Janet says. “He had to be sure he was fast enough and his garage was like an operating theatre as he meticulously checked out his bike before every meeting. He saw all of that as part of his duty of care.”

Wanting to know what it was like “to be on the inside”, John even tried racing himself on a GSXR1000 Suzuki at Aberdare Park and on the Irish short circuits.

“How can you give advice if you don’t know what you are talking about?” he said. Although he laughed at the suggestion that his insight into competition helped improve his bedside manner, there was no doubt that it increased the respect and affection in which he was held by the racers.

Working with fellow physicians in the MCUI Medical team also provided John with inspiration.

“I was watching experts at work in the team.” John told me. “I saw them descend on someone who had crashed and was in the active stages of the dying process and they turned that around. That is a very seductive thing and I aspired to be like those people.”

His medical skills were long in their gestation: five years of medical school, a year as a pre-registrar and seven more years of combined training and practice eventually provided him with a double consultancy as an anaesthetist and intensivist in a Co Armagh hospital.

As is often the case among people who work in extreme circumstances, Dr John had a wit that was Saharan in its aridity, with a propensity for black humour to match.

“I’m a bit of a jack of all trades in the medical world.” was how he described his doctor’s skillset. “It means that I can fix stuff as well as knock people out – and of course these skills are very transferable to dealing with crashes.”

Although John was to eventually become the leading light in the MCUI Medical team, he never sought to lay claim to any of the team’s numerous “saves”. Self-effacing and quietly spoken, he prefered to use “we” rather than “I” in his conversation, emphasising the importance of the squad’s tightly co-ordinated approach. And although highly respected by fellow professionals and the racing community alike, John shied away in life from the type of exposure that has surrounded him following his death. He preferred the company of close friends, socialising with some of the paddock’s lesser known names.

“John was a real race fan.” Janet says. “We booked our whole holidays around the racing calendar and he would record and watch every MotoGP and TT. Because he was out on track when he was working he was never sure who was winning and I had to be able to tell him who finished where when he got back in. He enjoyed meeting all of the top riders and chatting to them. Some, like Guy Martin, even stayed at our house, but John didn’t do celebrity and he would be shaking his head about all the attention that he has had since the crash.”

The loss of Myles Byrne, one of his closest friends, in a crash at Skerries in 2010 hit John very hard.

“I rode back to the paddock and cried my eyes out.” he told me after his best efforts had failed to save his friend.

“John was very close to Myles and his death had a huge affect on him.” Janet recalls. “Typically though, he dug his heels in and resolved to develop his resuscitation techniques even though it wouldn’t have helped Myles. He was driven on to improve by his loss.”

John’s hands on approach at the very pointiest end of medical care exposed him to some of the toughest trauma challenges imaginable. Calling on the experience he gained, he began to deliver lectures all over the world to medical conferences, gaining international recognition for pioneering techniques that were developed through the treatment of injured Irish road racers.

“I have always been drawn to the high acuity stuff because dealing with the sickest patients pushes you to really think on your feet.” he told me last year. “That is what I got into medicine for and provided me with the model of what a doctor should be.”

Irish bike racing is still reeling from Dr John’s loss but his mentor, Dr Fred, has vowed to continue.

“Nobody did it as well as he did.” Dr MacSorley says. “But I’ll have to find someone and train them up, and continue to do my best for patients at the side of the road.”

John’s work in areas such as the previously unrecognised Brain Apnoea Syndrome brought him professional plaudits amongst his medical peers – and new opportunities. Job offers came from Dubai, Sydney, and even the military.

“A few years ago the British Army made determined efforts to recruit John to work for them with injured soldiers on the front line in Afghanistan,” Janet says. “He was very tempted by the that because the military had all the very latest technology and equipment at their disposal but in the end he decided to stay and work in Northern Ireland.”

One cause that John felt passionately about was the need for a full air ambulance emergency medicine service for Northern Ireland, and he had begun to campaign for this before his untimely death.

“John was very, very opposed to needless deaths and statistics show that perhaps as many as 600 people who have been involved in accidents in Northern Ireland since 2003 would still be alive today if we had this service.” Janet explains. “An air ambulance service has been seen as a luxury rather than a necessity but John saw it as a fundamental need and had began to push for it’s provision.”

Janet and the rest of those now involved in the HEMSNI air ambulance campaign are determined to see the service introduced as part of John’s legacy.

“John wanted the very best for the place where he loved living.” Janet says. “ He went to Australia in 2014 and saw the HEMS system in operation there and came back frustrated that we didn’t have something like that at home. After that he started the campaign and if there is going to be anything good to come out of death it will be a HEMSNI service.”

The Lazarus kit

“In medicine you generally find that the usefulness of a doctor is inversely proportional to the size of the bag that he carries.” Dr John Hinds said with just a hint of a smile as he unveiled the contents of his famous orange kit bags in an interview just before his death. There was a minimal but critical amount of gear in the four pouches strapped to the Flying Doctors’ waists and in the small rucksacks slung on their backs.

“We only carry what we need and it has been pared down by experience.” John said.

Can the contents of this magic bag bring people back from the dead? Could it raise Lazarus?

“That’s what it’s designed to do.” he smiled.

Fully stocked the bags weigh 20kg and contain over A$6000 worth of drugs and equipment. In addition, Dr Fred always carries a defibrillator and oxygen bottle that costs more than A$4000.

“The outside two pouches contain the things that we need first and in the most hurry – cutters for slicing through leathers and painkilling injections. Riders often ask you for one of those just as the race is about to start!” John laughed.

The inclusion and layout of every item has been carefully considered and meticulously honed to a precise purpose. Speed of access is the critical concern and each bag is clearly labelled so that it can be read upside down.

“When you are in a ‘get me’ situation everyone can see where everything is.” John explained.

Tourniquets and clamps are stored alongside the radio, vital for calling in back-up. “We have enough kit on board to deal with two patients each and if we need more we can call in the team in the van. They carry all of the big stuff like spinal vacuum mattresses.”

John demonstrated the way the kit bags could act as a shield around the patient when they were unstrapped and placed on the ground.

The two central pouches contain the bigger stuff, instruments that are needed “if things are really bad”. Chest drains, pre-prepared doses of anaesthetics, scalpels and forceps sit side by side. There is even a small waste bin for discarded needles and dressings. Every piece of kit has a vital part to play in a step-by-step treatment process that is designed to eliminate life-threatening dangers.

“If they don’t get better after each thing you try you move on to the next thing.” John said. “A collapsed lung is almost always a factor with those who are worst hurt but we have refined the kit we need to deal with it to a minimum. In a hospital you might have a dozen sets of forceps but we just carry one set and a scalpel in a sterile pack. We make an incision in the chest wall and push the forceps in to open the chest to allow air in.”

Characteristically, he made it all sound so simple. They do say that a good workman is only as good as his tools, but it was the extraordinary skills of John and his colleagues in using this equipment that saved so many lives.

One man who has first-hand knowledge of Dr Hinds’ skills is Ireland’s most successful road racer, Ryan Farquhar. Dr John and Dr Fred were the first doctors on the scene when he suffered the worst crash of his career at Cookstown in 2006.

“I looked down and I saw that my arm wasn’t where it was supposed to be.” Ryan recalls. “I was in a lot of pain and could hardly breath. Then I saw John and Fred and they gave me injections and I felt a lot better very quickly. I knew they were having trouble getting a pulse but they sorted it. If it hadn’t been for their quick action I probably would never have been able to race again. Being on bikes they were with me in seconds and it is that that makes the difference between life and death. There is no doubt that John will be very sorely missed.”

Medical breakthrough

As a direct result of experience in treating race injuries Dr John Hinds, Dr Gareth Davies and Dr Mark Wilson highlighted a previously unrecognised condition called Brain Apnoea Syndrome. The details of the syndrome – and a ground-breaking new approach to its treatment – were discussed during the Trauma Medicine conference in London earlier this year.

“When someone receives a blow to the head in an accident they often appear to be dead.” Dr Davies explained. “They can suffer dilated pupils, there may be no pulse and they will stop breathing. You could walk away and say that they have suffered an overwhelming injury and that they are dead and if you do nothing they will die.

“This is something that we get to see in bike racing very, very quickly. Our work in the sport gives us a unique perspective because we are on the scene of crashes so fast, something which usually only doctors who stumble across accidents get to see and write about. As a result we now realise that there is a likelihood that this can happen to all patients who suffer a serious head injury whether it be in a motorcycle accident, a car crash, falling down stairs or falling off a bicycle, and we want to raise awareness so that people can do something about it. If they are given CPR, if someone can breathe for them, then they will often revive.

“We need bystanders to be able to do this – a biker’s mates for instance who have been out riding with him – because usually an ambulance wont get there in time. All it requires is a knowledge of simple First Aid processes such as CPR.”

It will also require breaking an accepted shibboleth in dealing with bike crash victims as Dr Davies explains.

“Very often there is an obsession with not touching rider who is down,” he says. “The big thing is not to take the helmet off because of the fear of spinal injury, but if a rider suffers brain apnoea syndrome following a blow to the head just standing there waiting on emergency services to arrive will almost certainly lead to death. If there is no pulse and the rider is not breathing, the ‘Don’t touch’ mantra doesn’t apply, and whoever is present needs to perform some basic life support.”

The doctors recommend that everyone should learn how to remove a helmet safely.

“Basic First Aid techniques such as chest compression and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation require no specialist knowledge or equipment but if there are no signs of life then you need to know how to get on and do it.”

The identification of phemomena like brain apnoea syndrome is a direct result of practising medicine in the harsh realities of race crashes.

“Groups of clinicians working together in pre-hospital care leads to innovation.” Dr Davies says emphatically. “When doctors were ‘let out’ of hospitals and began working in motorsport they were able to bring their hospital practice on to the streets.”

This exchange of information has become a two-way street with techniques that have been honed in race medicine being brought into widespread usage in general emergency medicine.

“Equipment pioneered at races is now being used regularly by the ambulance service. Our capability for advanced damage control surgery at the roadside and the ability to deliver an emergency anaesthetic, including controlling the airway and breathing, have all been developed in treating race casualties and these have now entered mainstream pre-hospital care.” Dr Hinds explained.

Accident death: the real causes

“There are only about half a dozen things that can kill you as a result of a traumatic accident – and only about four of those are treatable.” John explained to me before his accident. “A major head injury, a high spinal injury that prevents breathing, a collapsed lung (very common), bleeding in the belly, bleeding in the pelvis (this is like a bucket) and bleeding elsewhere such as from a lost limb or an open fracture are the biggest problems. Bleeding is bad because you only have about five litres that you can waste before you are in serious trouble.” he explained.

“So basically the biggest dangers come from head or chest injuries and anything that causes major bleeding. When you are dealing with injuries like these you are working at the very extremes of life and the patient either gets away from you or you bring them back from the brink. Those are the days that put manners on you.”

The other big challenge for Dr John and the rest of the medical team is the environment and the conditions in which such injuries were encountered.

“I have had to deal with incidents where the injured parties have gone over the edge of a cliff or landed in a lake.” John recalled with a grimace. “Conditions can be very hostile in these circumstances and sometimes you have to deal with that first because it could kill the patient before their injuries do. If someone is stuck under a burning sidecar they have to come out of there before you do anything else.”

I asked him if there were ever any situations where he knew it was hopeless, that he was beaten before he even started?

“In the most serious crashes there are two types of people that we see.” John explained. “The victims are either already dead or in the process of dying and there have been times when there has been no heartbeat and we have brought them back. That is why we do everything for everybody, no matter what the situation or circumstances.”