The Tasmanian Motor Cycle Club (TMCC) holds a very proud place in the history of motorcycling. Formed in 1905 as the Tasmanian Automobile Club (TAC), it’s the third-oldest continuously run motorcycle club in the world.

It began in Launceston with a band of enthusiastic people involved in what detractors said was just a passing fad, because the motor vehicle would never replace the horse!

It probably helped that the bigwigs of Launceston’s newspapers, John Hart and Gordon Rolf, were both very active committee members and keen club competitors.

In the beginning, the car owners tended to be from the top end of town. They employed a chauffeur to not only drive them around and mechanically maintain the car, but to also race them in competition events.

The bikes were ridden by business owners, to get to work and to see clients. Doctors also found them quicker for emergency house calls, rather than saddling up a horse (or dragging the chauffeur out of bed).

Cecil Dyer, an original committeeman, keen motorcyclist and trained engineer, soon became a major force in the club. Intelligent owners quickly realised it was a good idea to invite him along on any excursion, because if something went wrong there was a good chance Dyer would be able to fix it.

It also didn’t take long for Rolf to realise that Dyer was at most motoring events, and he became a regular motorsport columnist for The Examiner. As was the case with most columnists of the time, he wrote under a nom de plume and, until he enlisted in WW1, ‘Spark’ was the voice of the club.

By the 1950s, the TMCC was running almost 20 events a year and the list of mainland riders who competed over the years is incredibly long. And not just riders; a Victorian official was shipped in for the club’s first event in 1906 to show TAC how to organise handicapping of riders.

Team owners came with their bikes from Victoria for race meetings held on the Longford horse racing track in the 1920s, where Victorian star Charles Disney had to fight for his victories against some very quick local first-timers.

When racing returned to Longford three decades later, on the road course, the Victorian contingent was looked after by Percy Quincey, whose son Maurie was doing well on the track.

Percy would arrive early on the ferry with a load of bikes and a few riders turning the March long weekend into their annual holidays. The rest arrived by air just before the weekend. It wasn’t until the end of the 1950s that the ferry became the roll-on roll-off ship out of Devonport.

Even though Bass Strait has been a big barrier to cross-pollination, many riders over the years headed north to compete.

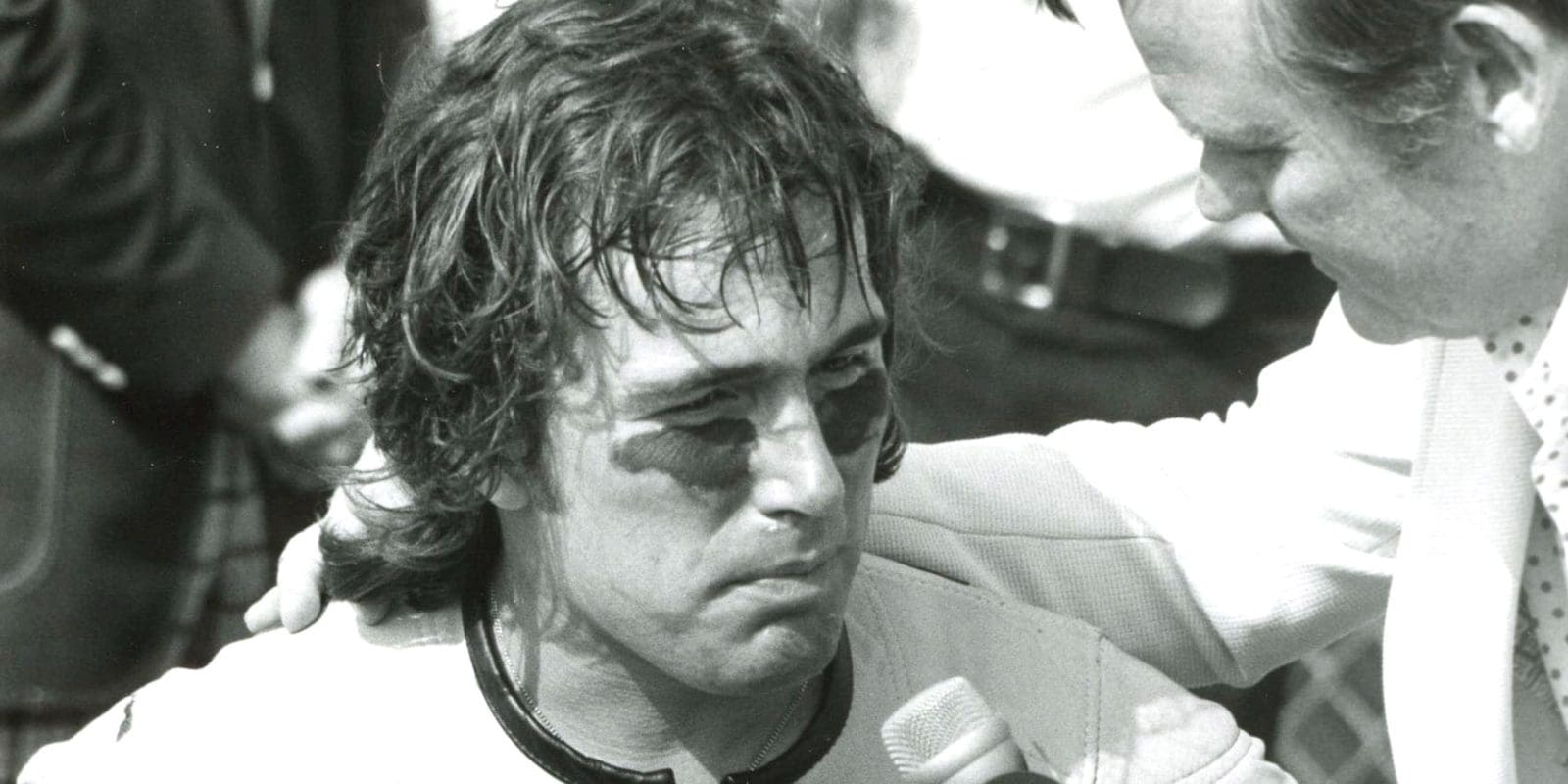

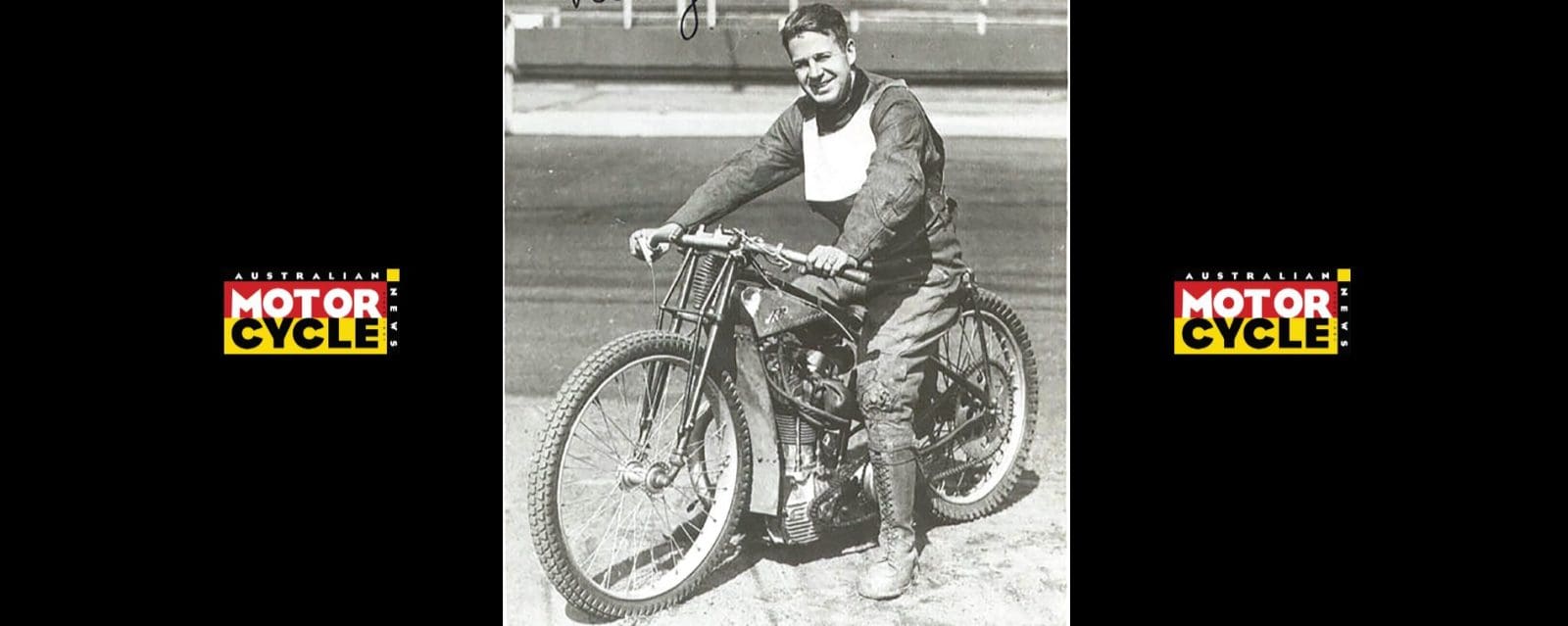

Among the first was Reg Hay, who was the eldest son of Launceston dealer Charles Hay and found his talent at the Longford horse track. In the late 1920s the developing sport of speedway caught his attention and he would spend the summer winning at speedway and grass tracks in Victoria, while in winter he was home in Tasmania winning the TMCC 24-hour trials.

Hay moved to England just before WWII to captain the Australian Speedway team. He returned to Tasmania after the war and rejoined the club as the chief starter at Valleyfield, Quorn Hall, Longford and Symmons Plains.

The early days were a veritable who’s who of well-known names, none more so than the complex King situation.

The two King dynasties ran parallel from the start, when they each moved from Hobart to Launceston to set up motorcycle shops. John King’s dealerships included Indian and Triumph as the backbone. Tadius Simmion (‘Sim’) King had Harley-Davidson and BSA and lasted so long that his siblings had Suzuki.

Three generations of Kings on both sides had a major influence on the club, and practically all spent time on the committee. They provided their time as committeemen, trophies for competition, and advertising results of club-run events where their bikes performed well.

Some names became even better known nationally, especially as these spirited competitors were also successful businessmen.

Second-generation brothers James and Robert Boag were a good example, as they took their Launceston brewery a long way to where it is today while racing bikes.

But probably the biggest dynasty was the Fysh families. Two brothers, Phillip and Gordon, were regular winners. Gordon imported the first ABC into Tasmania and regularly won on it. Phillip lent more to administration, and for a number of years was the club president. Their father, Sir Phillip (senior), was the club patron, but his big claim to fame was that he was the Tasmanian premier and part of a five-man delegation instrumental in forming the Commonwealth of Australia. In fact, start, when they each moved from Hobart to Launceston to set up motorcycle shops. John King’s dealerships included Indian and Triumph as the backbone. Tadius Simmion (‘Sim’) King had Harley-Davidson and BSA and lasted so long that his siblings had Suzuki.

Three generations of Kings on both sides had a major influence on the club, and practically all spent time on the committee. They provided their time as committeemen, trophies for competition, and advertising results of club-run events where their bikes performed well.

Some names became even better known nationally, especially as these spirited competitors were also successful businessmen.

Second-generation brothers James and Robert Boag were a good example, as they took their Launceston brewery a long way to where it is today while racing bikes.

But probably the biggest dynasty was the Fysh families. Two brothers, Phillip and Gordon, were regular winners. Gordon imported the first ABC into Tasmania and regularly won on it. Phillip lent more to administration, and for a number of years was the club president. Their father, Sir Phillip (senior), was the club patron, but his big claim to fame was that he was the Tasmanian premier and part of a five-man delegation instrumental in forming the Commonwealth of Australia. In fact, the Canberra suburb of Fyshwick was named after Sir Phillip Fysh.

Cousin Hudson Fysh didn’t do too badly either. After finishing his racing, he headed to Queensland and formed a company known today as Qantas.

The original TAC charter was that the club was to be split evenly between car and bike membership. The club could run car races in the morning with bike members as officials and reverse it for the afternoon.

As well as competitive events, the TAC was heavily involved with the government in forming laws for motoring, consulting with councils on speed limits, and was often tasked with erecting warning and directional road signs on the councils’ behalf.

After WWI, returning soldiers were restless and needed more competitive events. So, with the blessing of the main committee, a sub-committee morphed into the Northern Tasmanian Motor Cycle Club (NTMCC).

It has never forgotten its roots and still has a very good relationship with local car clubs. Up until the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS) was formed in the early 1950s, the club would organise beach, air strip and Longford races and invite the car clubs to run support events. It was always a good idea for race meetings to be combined car and bike meetings, with Symmons Plains often running up to 25 events in an action-packed day of racing.

After WWII, the NTMCC successfully applied to the ACU-GB to be the governing body for motorcycle sport in Tasmania on the proviso that it represent the entire state. The word Northern was dropped from its name and it became the Tasmanian Motorcycle Club.

Again, returning servicemen craved excitement and danger, and following the success of Longford’s grass track meetings in the 1920s (an often-misunderstood belief is that Longford was a car meeting) the club branched out into beach events; time trials, record attempts and racing.

Beach racing became big for the riders and mechanics, and many Australian records were set on Bakers Beach by men such as Frank Hallam, who went on to become a major figure in Jack Brabham’s Repco F1 project.

Local AJS agent, Trevor Jowett (who would also write regular and insightful motorsport columns under the nom de plume ‘Megaphone’) surprised everyone when he bought the factory-built 998 AJS record attempt bike from the estate of the rider who lost his life on a Brough Superior in Europe trying to set a land speed record.

But one of the best engineers was Bill Gough, who built his own special that became the first Australian-built bike to top 100mph.

Three airstrips became available at the end of the 1940s – Quorn Hall, Valleyfield and Tunbridge. They were originally grass strips that had been paved with concrete or bitumen to be able to take bombers during the war. The idea was that, if Japan invaded Australia, the bombers could be regrouped in Tasmania and a counter-attack launched by Tasmania to save the mainland.

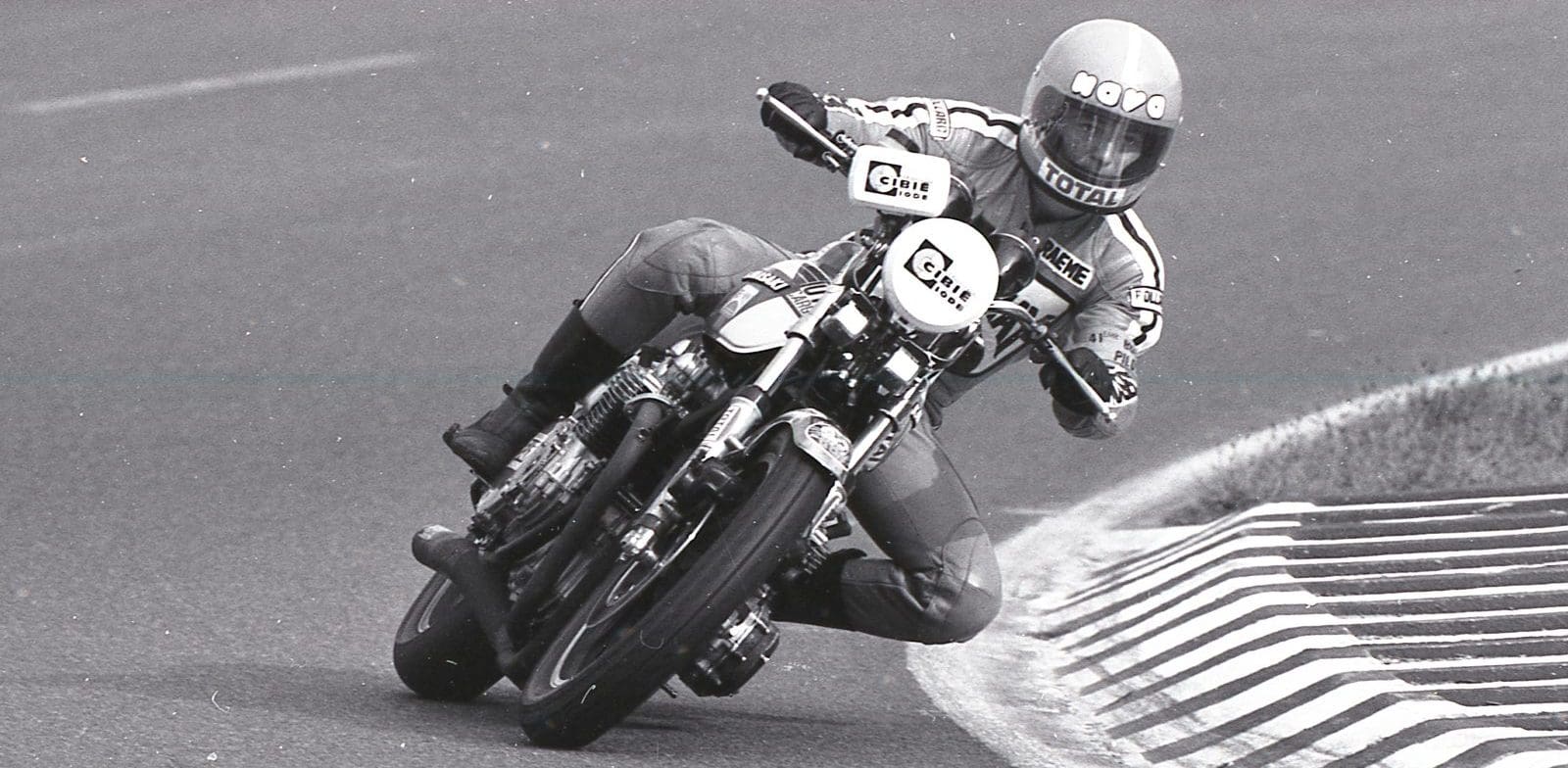

By the mid-1960s, as Bob Dylan was telling us, the times they are a-changing, Baby Boomers were about to leave school and a new player, Japan, was starting to make decent motorcycles. This would become the golden era of Japanese GP race and long-distance production bikes, which opened up racing to a whole new style of competition. The club ran its share of these races with the annual Australian Road Race Championship round and an annual long-distance production race.

While it might be noted for its long history in road racing, the Tasmanian Motorcycle Club has never shied away from any genre of racing. Among the first bold adventures was racing on the Longford Horse Track, with paying spectators. Then came beach and airstrip racing, before what’s possibly the club’s proudest milestone – instigating the Longford road circuit.

The road trial events after World War II were tough and very popular. They were up to 24 hours in duration, run on a combination of highways and bush roads during Tasmania’s harsh winter.

The TMCC was one of three clubs to assist John Youl in building a circuit at his Symmons Plains property, and it has promoted almost every motorcycle race there since.

Words Ken Young Photography TMCC Archives & KY