While Barry Sheene, Kenny Roberts and newcomer Randy Mamola chased each other around Le Mans, a group of white-clad Japanese Honda R&D staff hunched around the world’s two most technically advanced motorcycles in the back of the pits. They radiated frustration. Mechanics had worked through the night to rebuild the fragile engines, riders had done their utmost in practice among the rampant and much more powerful two-strokes. But still Honda’s magnificent new four-stroke engineering tour de force had fallen short. It had failed to qualify for the French GP of 1979.

The factory team had wheeled it out anyway, to the back of the grid, in case they might be allowed to start as reserves, as at the British GP, the bike’s inglorious debut three weeks before. Not so. At first, petulantly, they refused to withdraw, spectators in the stands baying – they wanted to see these radical new bikes running. The start was delayed as the altercation continued. Finally, ignominiously, the bikes were wheeled away.

It was one of the lowest points so far in the short and ultimately massively under-achieving life of the Honda NR500, which earned more unkind nicknames than race victories, and never scored a single world championship point in two years of intermittent effort. The great attempt to make a four-stroke that could beat the two-strokes was over.

What doesn’t kill you…

To write the NR500 off as a failure, however, would be to miss the point completely, especially from the point of view of the leader of that dispirited group at Le Mans and his colleagues back in Japan. He was Takeo Fukui, the NR500 project leader. The others were Suguru Kanazawa, the engine man, and Satoru Horiike, the engineer behind the groundbreaking monocoque chassis. Recognise the names? Fukui became president of Honda Motor – the boss of bosses – from 2003 until retirement in 2009; Kanazawa president of the Honda Racing Corporation before moving on to head Honda’s UK Manufacturing plant; while Horiike worked alongside Kanazawa as MD of HRC. Kanazawa told me: “The NR500 was our teacher,” and the lessons served not only the individual engineers but also Honda’s racing DNA, still evident in the dominant RC213V V4 that won the MotoGP championship in 2013 and 2014.

The radical V4 NR, with its oval pistons, upside down fork and giddy 21,000 rpm rev ceiling, casts a shadow that reaches into MotoGP today. While there is superficially little in common, the NR informed the design of both the V5 and the V4 RCV racers in practical approach and in overall philosophy.

As Horiike told me, although there is no single design element you can put your finger on, the RCV is of the same family. “I can’t explain exactly, but I feel like there is red Honda engineering blood in the RCV, from the NR. It is not each component, but the Honda engineering spirit is the same.”

Sentimental tosh? Not in this context. Honda’s future top managers learned an awful lot about racing and about engineering in the course of this apparently futile exercise. They also demonstrated Honda’s stubbornness, even pig-headedness – and the company’s trademark insistence that engineers and engineering should always lead the way. More than just an ultimately hopeless attempt to stem the unstoppable two-stroke tide, the NR500 was a highly significant engineering experiment conducted (frequently painfully) in public.

Novelty was part of the brief. The project was quite separate from the old racing department, and was developed in the new R&D facility at Asaka on the outskirts of Tokyo (now headquarters to HRC). Development was deliberately put into the hands of racing novices. As Horiike remembered: “There were almost all new people, who knew almost nothing about racing. We had to use radical technology.”

Honda had quit racing after 1967, having won championships in every class except the 500 – they came close, but never managed to defeat the reigning MV Agustas. MV’s eventual nemesis had come as late as 1975, from Yamaha and Suzuki, with the new two-stroke generation. The equation had already been proved in the smaller classes: an engine of a pre-defined capacity will make more power if it is able to fire twice as often. Honda sought a new way of writing the numbers. In simple terms, they would have to make a four-stroke engine capable of revving twice as fast as the two-strokes. They would need 20,000 rpm or more – unprecedented in an engine that big, though below the 23,000 rpm ceiling of Honda’s twin-cylinder 50cc racer of the sixties.

Full-throttle creativity

New Honda president Kiyoshi Kawashima, who had taken their first team to the Isle of Man in 1959 and had now succeeded Pops Honda himself on his retirement, had presided at the 1977 launch of the stunning six-cylinder CBX1000 roadbike, which drew on Honda’s multi-cylinder racing experience. Kawashima stunned pressmen at the Suzuka launch, announcing that, after a t10-year lapse, the world’s largest motorcycle company would be returning to the GPs.

The project had three aims, as Horiike explains: “to develop radical technology, to win for the Honda firm, and to train young engineers”. Fukui was made project leader, Kanazawa was in charge of the engine, Horiike the chassis. The brief was to design a two-stroke-beating racer from scratch, with new technology. In line with this blue-sky approach, the machine was christened NR500 – for New Racer.

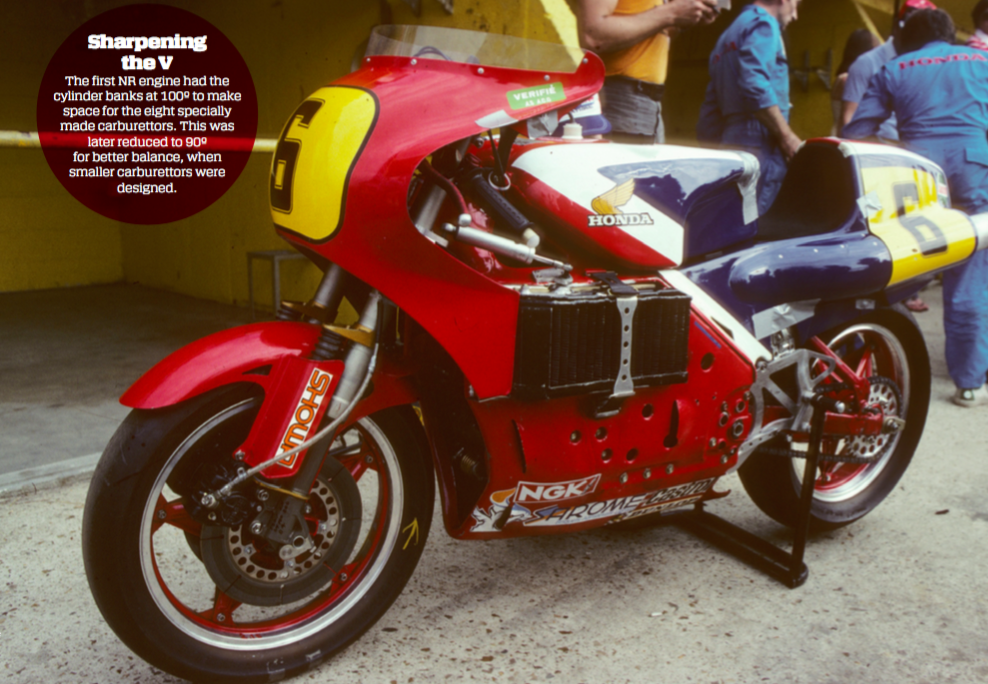

The design was announced early in 1979, and it certainly was radical, a complete departure from racing and indeed engineering convention. In retrospect, it was very far-sighted. In the course of its brief life, the NR500 pioneered several useful features, some many years ahead of their time, including carbon brakes, ‘upside-down’ forks, a rising-rate rear suspension linkage, and the slipper clutch, all now common fitment in MotoGP. Some of these then disappeared for many years – it was a decade before carbon brakes came into common use, and Kanazawa explains that, with the forks, “the idea was good. The problem was getting the accuracy of machining at that time – they had very small tolerance.”

The NR project went down several blind alleys as well. Original plans for ceramic pistons and liquid-nitrogen cooling were abandoned at an early stage. The highly original pressed-aluminium monocoque chassis made it further. With composite wheels and side-mounted radiators it was the cause of frequent overheating, along with valve and valve spring breakages, and other sundry failures in early testing. The insistence on a low frontal area meant that 16-inch wheels were specified, requiring a new range of custom-made tyres. (Sixteen-inch fronts also would be adopted by others within three years.)

But the most striking innovation was within. The NR500 had oval pistons!

This wasn’t a first – Triumph had drawn up just such a cylinder shape before World War Two – but Honda was the first to make it work. In the company legend, the idea hit a fatigued R&D chief Shoichiro Irimajiri, on his way home after another late night at Asaka, from the oval board behind the traffic lights where he was waiting for the green.

Like many design elements, it was forced by the regulations. Honda wanted to build a multi-cylinder engine, perhaps a V8, to get the small short-stroke cylinders they would need to make high revs, but rules dictated a maximum of four cylinders. The oval pistons (strictly speaking not truly oval, but with parallel flat sides) meant they could replicate a V8: each cylinder had eight valves, two spark plugs, and two connecting rods, although a single piston and combustion chamber. The engine had a very short stroke of 36mm at first, reduced further in later versions.

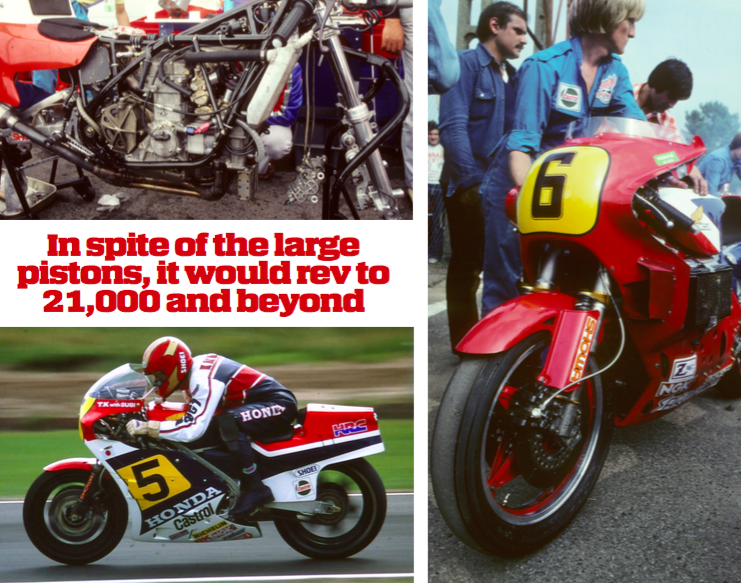

It was Honda’s first V4, the first of many to follow, and an engine of great imagination. And revs. In spite of the large pistons, it would rev to 21,000 and beyond, and in its first version make power to 17,500 rpm. (This first one, with no flywheel, ticked over at 7000 rpm!). These figures remain beyond the reach of the current MotoGP machines.

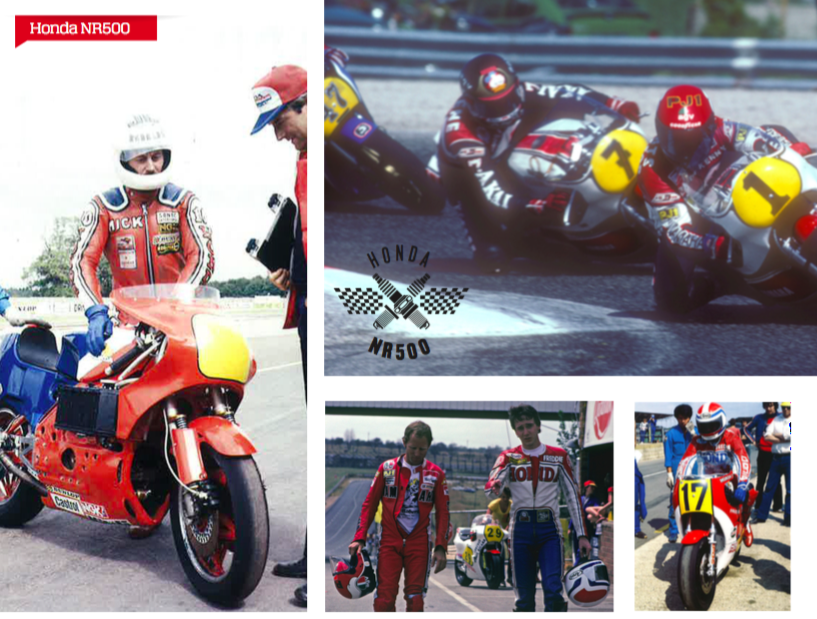

TOP: While Katayama was on the grid in 1981, he was rarely in the mix in a season dominated by the two-strokes of Lucchhinelli and Mamola (Suzuki),w and Roberts and Sheene (Yamaha, shown above)

ABOVE LEFT: A young Freddie Spencer (right) with Kenny Roberts

ABOVE: Spencer did ride the NR500 on a few occasions, including perhaps its best performance ever at the 1980 British GP. Spencer was running fifth when the engine expired

The salient feature of the whole design was its originality – the hallmark of freshly graduated engineers full of brilliant ideas unsullied by the hard school of experience. This was its great strength, and its even greater weakness. The most successful racing philosophy is quite different: what succeeds is what succeeded last year, plus a few per cent. But the design brief said otherwise.

As Horiike points out: “Now, everybody thinks that is it better in racing to be conservative. But at that time we thought completely different. In Honda we need to have some kind of new technology for the future, in racing now. If we don’t, nothing happens for the future.”

Kanazawa, on the same topic, was succinct. Was the engine too complex? He shook his head. “Must be complex,” he said.

This is the nature of experiment. Even if the ideas get discarded, it means they have been tested. Many ideas incorporated in the NR500 were discarded.

One of the first to go was the monocoque chassis – Horiike’s hobby horse. “All racing bikes had a fairing. We used the fairing as a chassis,” he said.

The monocoque comprised a pair of aluminium pressings, joined at the front by the steering head structure, and cradling the engine. The swing-arm was attached directly to the engine casings. It was prone to cracking. Test rider Mick Grant recalls it requiring welding frequently throughout the day on his first encounter. The design had one major advantage: low weight. “The first one was very light – maybe half of a steel tube frame,” said Horiike. And one major disadvantage: engine accessibility. There wasn’t any, for an engine that was notoriously finicky and demanding of attention. Even changing the jets or sparking plugs (eight of each) required splitting the chassis; routine maintenance was more than just irksome. “There were many bolts from the chassis to the engine,” Horiike recalls. “So many bolts – 18. All six millimetre. I clearly remember that. To reach the engine, you must do this.” Now, 27 years later, Horiike cites one of many lessons learned from the NR500 – “How to use the time. In racing, time is the most important thing.”

Left: Katayama kept riding in the 500s after the NR500 was retired and came fifth in 1983

Ready to race?

It was in this form that the bike appeared in Europe for the first two races, a nightmarish debut that was worse even than people saw. Mechanical fragility was such that Honda had to introduce a night shift – a separate team of mechanics away from the track, working unseen to rebuild the engines, a job that took eight to ten hours.

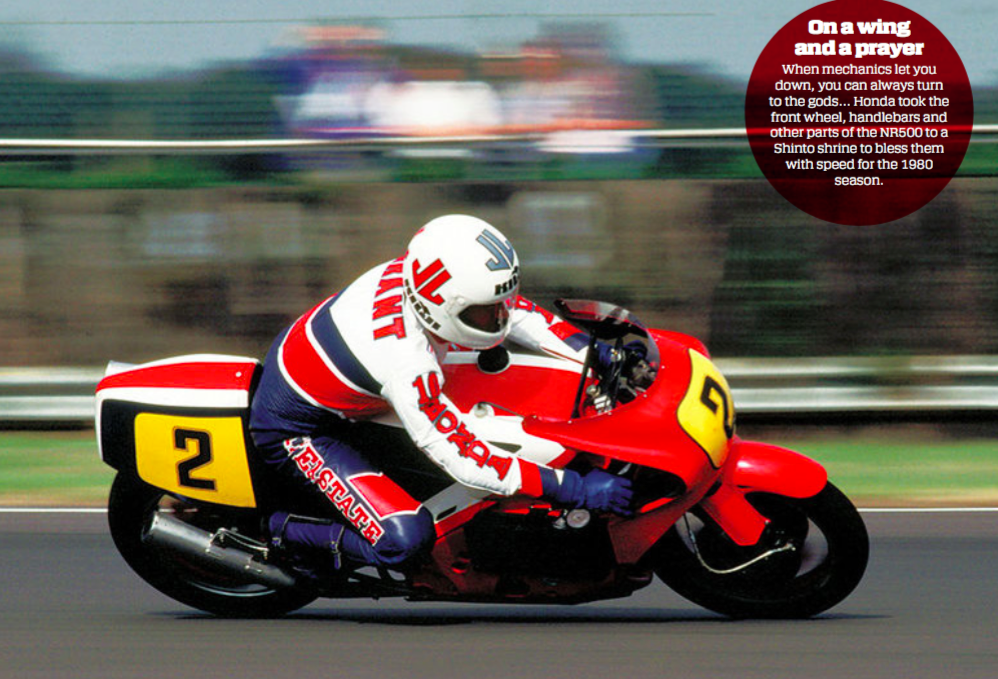

There was another operational difficulty: GPs then had a dead-engine push start, and the NR500 – with its high compression and reluctance to run below 7000 rpm – was very difficult to push-start. “You had to be something of an athlete,” says Grant, who along with Takazumi Katayama was signed up to ride the new bike. The debut was at Silverstone, with the semi-retired Soichiro Honda present. Katayama just qualified, Grant did not, but was allowed to start. Katayama got away at the back, but Grant had trouble firing it up. When he did get going, he made it only to the first corner, where the bike crashed as he leaned it over. There was even a small fire.

Grant explained it to me, many years later. “They didn’t want me and Katayama coming last and second-to-last, so they told us they only put in enough fuel for a few laps and to put on a bit of a show then stop. I missed starting it on the first bump. I finally got it going on the third or fourth, but by then I was so far back on the seat that it went onto the back wheel. It had never done a wheelie before – didn’t have enough power. What I couldn’t see was that the back wheel was covered in oil. That first year it had such massive blow-by on the flat sides of the piston that it needed a huge crankcase breather. Doing a wheelie put the breather tube below the level of the oil, and it pumped it onto the back wheel. Afterwards, Mr Fukui said to me: ‘No more wheelies’.”

Three weeks later came the debacle in France, and the Honda men withdrew for the winter, bruised and battered, but still inspired by the quest. There were many problems to be solved, from simple reliability to the need for significantly more power.

Engine work was of course done in house, and the second version was much improved. It had a slipper clutch to avoid the wheel-hopping that struck when closing the throttle even in the higher gears, and it had been civilised to the extent that Grant remembers it idling sweetly at closer to 1000 rpm than 7000. Development continued, with some quite fundamental changes, including reducing the vee angle.

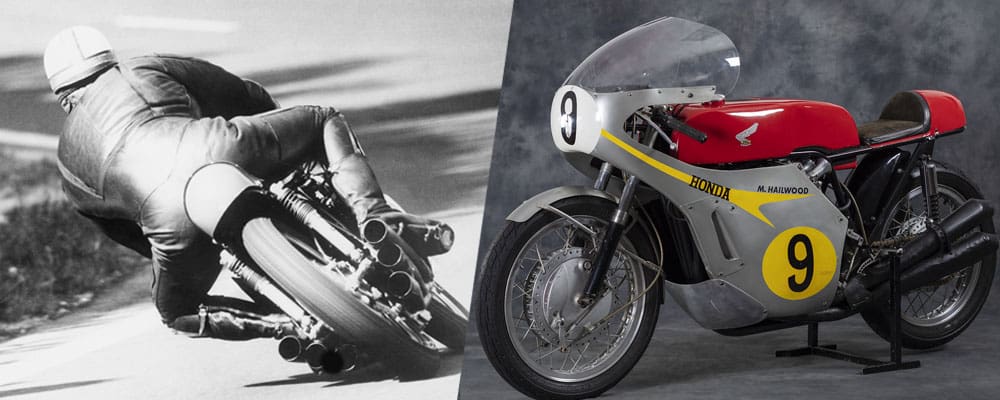

Most significantly, the clam-shell monocoque was abandoned, and Honda turned (as they had back in the days of Mike Hailwood) to Britain for a thoroughly conventional chassis made in round steel tubing, built by Ron Williams of Maxton. The cooling system was also conventional – the radiator out front. The work took much of the year; it reappeared for the Finnish GP in July, round six of eight. Katayama qualified, but the effort had left them without any race-worthy engines, and he withdrew. He qualified again at Silverstone, and finished … last; but gave the project some heart with 12th at the old Nürburgring.

The bike had gained power all the time – the inadequate 100hp (74.57kw) of the original up to 110hp (82kW) for only the second race, and to 120hp (89.5kW) by the end of the next year. In its final form it would just reach 130hp (97kW), said Horiike – finally meeting the original target. For its last year, it was completely revised again, with the engine canted forward so the front cylinders were close to horizontal. It would be run out of Britain, from the newly formed HIRCO (Honda International Racing Corporation).

With the teething troubles behind it, the machine achieved its first race victory in a national event at Suzuka. But although the numbers were right, it was still not truly competitive – the need for revs its downfall. Ironically, the lower-revving two-strokes had more midrange torque, which as MotoGP has shown is the Holy Grail for fast corner exits.

Katayama struggled on in 1981. He came 13th in the opening GP in Austria, retired in Germany with brake trouble and crashed on his own leaked water at a baking Paul Ricard in France, before having his best ever race at Assen, where he was running 10th, in line for the machine’s first world championship point, when the ignition failed on the final lap.

By now the big decision had been taken – by Fukui, en route to an increasingly senior managerial role, via presidency of the HRC corporation that grew out of HIRCO. The project would be stopped at the end of the year … Honda were going to do it the other way, by building a two-stroke. The rest, as they say, is history, and it would be Freddie Spencer who would bring Honda their long-awaited first 500-class World Championship just two years later.

The NR legacy

When the new MotoGP four-strokes broke cover in the late days of 2001, it was clear Honda had put the most thought and effort into preparation. The RC211V five-cylinder would start and finish as the ultimate 990.

To what extent did Honda’s new four-stroke paragon spring from the NR500?

The machine was informed by the NR500, and of course by succeeding Honda four-stroke V4s (including the showpiece oval-piston NR750 road bike), but it had little in common in detail. Except that it showed the effect of lessons learned in the negative: don’t go racing until the machine is ready, don’t test new technologies up against established technologies, don’t make a machine that is unfriendly to rider and mechanics, and especially don’t disregard everything you and your engineers have learned in the past.

The RCV has round pistons, for one thing – this is as much a matter of regulations as design. As Kanazawa said: “Maybe oval piston is stopped now. It’s only sleeping. If we have a circumstance of getting the oval piston, we will produce it again.” Different minimum weight regulations might have tempted him to take the oval-piston V3 990 design further than “only in my head”, back at the dawn of four-stroke MotoGP.

The lower-revving modern engines also have plain crankshaft bearings where the NR500 had roller-bearings, but there is a lineage to be traced, especially when you deconstruct the engine design of the 75.5º V5. It is really a V4, the outer pairs of pistons on the same crank-pin, with an extra cylinder riding piggy-back in the middle, phased to counterbalance the others. It shares the DNA of all Honda’s V4s, of which the NR500 was the first. The next GP racer, the 800cc of 2007, was a true V4; and the current 1000cc bike has regained the 90º engine architecture.

Kanazawa agreed. “In the 1960s, we took many cylinders – like the six-cylinder 250 and 350. Then we stopped racing. We came back in 1979 with the V4 NR500. I think the origin of Honda motorcycles at the moment is the NR.”

The last word goes to Horiike: “We learned many things, especially the way to solve problems. When were not racing, we did not have this methodical way. We learned these kinds of things from the NR. I don’t think the motorcycle was a mistake. This was a success.”

RIGHT: After the NR500’s inauspicious run, Suguru Kanazawa (L) and Satoru Horiike went on to bigger and better things at Honda – hard to imagine that happening in today’s ‘results-driven’ world

WORDS MICHAEL SCOTT