It was his father’s cancer diagnosis that spurred Shane Kapitzke into designing and building himself a new left arm that would allow him to ride roadbikes again after a 25-year absence.

“My dad got cancer in his kidney, they didn’t think he was gonna make it,” begins Shane. “And we used to ride bikes together a lot, so I said to him, ‘how about I design and build an arm, I’ll get a bike and we can go for a ride together before you fall off the perch?’ And he was surprisingly open to it.”

The surprise element wasn’t so much the absurdity of his son’s willingness to create a mechanical limb that would allow him to ride motorbikes again – as a hugely competent designer and draftsman for the mining industry, designing a new arm is a relatively simple task for Shane – but because his family had warned him off bikes for good following the 1998 crash that eventually led to the above-elbow amputation of his left arm.

“It was two weeks before my son was born,” he said. “And you see, I’d broken my back the year before in a bike accident, and then I had this one, so they were like: ‘that’s it, you get back on a bike and we’re disowning you’.”

You could hardly blame them. A year after recovering from a broken back and just weeks before becoming a dad for the first time, Shane crashed his 1989 GSX-R750 “in a fast corner I’d ridden a million times before”, breaking every rib on his left-hand side, his collarbone, shoulder blade and his upper arm, as well as fracturing his C6 vertebrae, deflating his lung and rupturing his spleen for good measure.

“I don’t know what happened,” he said. “The bike, which they found a long way away from me, had low-side damage; a broken lever and scuffed fairing on one side. But my injuries were more like a highside.

“But I had no external injuries,” he adds. “The doctors said the two things that saved my life were that I was in really good shape physically, and that I had good gear on.”

Initially, doctors decided to try and keep Shane’s arm, but it had suffered peripheral nerve damage, something called a brachial-plexus injury, which meant Shane had no movement in the lower part of his arm, nor did he have any feeling in it.

“I could move my shoulder, but it was a dead arm, I s’pose, I couldn’t feel it. I’d injure it and I wouldn’t feel it, so it was a real risk to have it there.”

So 10 months after the accident, Shane’s left arm was amputated, which he said came almost as a relief.

“I was pretty keen to have it off, cos it was just slowing me down,” he says. “I’m fortunate to have had that period of time, psychologically, where I wanted it off.

“If I’d have woken up in hospital [he was in a coma for nine days] with it gone, it would have been tough.”

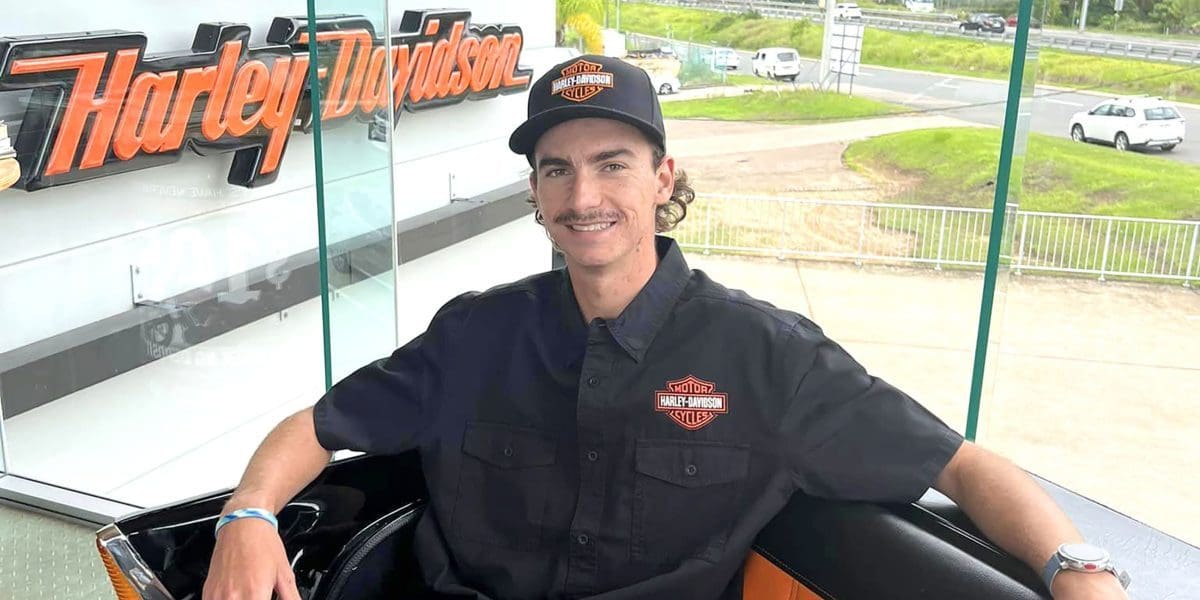

But two decades later, and with his old man’s blessing, he set about building himself a replacement. Not only did he have the skillset and resources to do it, the commercially available prothesis weren’t up to the standards a bloke of Shane’s skillset was used to.

“I hit the project at warp speed – totally focussed on it,” he said. “I had to get into good physical shape, develop some strength in my shoulder – I’d 3D printed a working model of the mechanism in this latest version, but it had a limited range of movement, so I hit my machinist up and we made it better.”

Having already built himself an arm that allowed him to drive a car, Shane was aware of the hoops he’d need to jump through at the Department of Transport in order for him to legally operate a vehicle using a prosthesis.

“It’s not flash, basically a stick on a stump. I went to the transport department and I had all of my engineering certificates and things for them to look at, and they said ‘we don’t really care about those, just as long as it doesn’t have any sharp edges’.

“With the [motorcycle] arm, as well as no sharp edges, it had to have an elbow in it and the elbow had to return to straight – so it couldn’t just be a floppy elbow – and that was it.”

To add further complexities to the project, Shane had three registered bikes in his shed which needed to be compatible with his self-built arm: an SWM enduro bike, a Royal Enfield Continental GT 650 as well as a Yamaha TRX850. And because the ‘hand’ on the arm merely allows Shane to hold on to the ’bar and make steering inputs, all of the controls traditionally actuated from the left-hand grip all needed to be moved to the right-hand side and setup in such a way they can all be operated single-handedly.

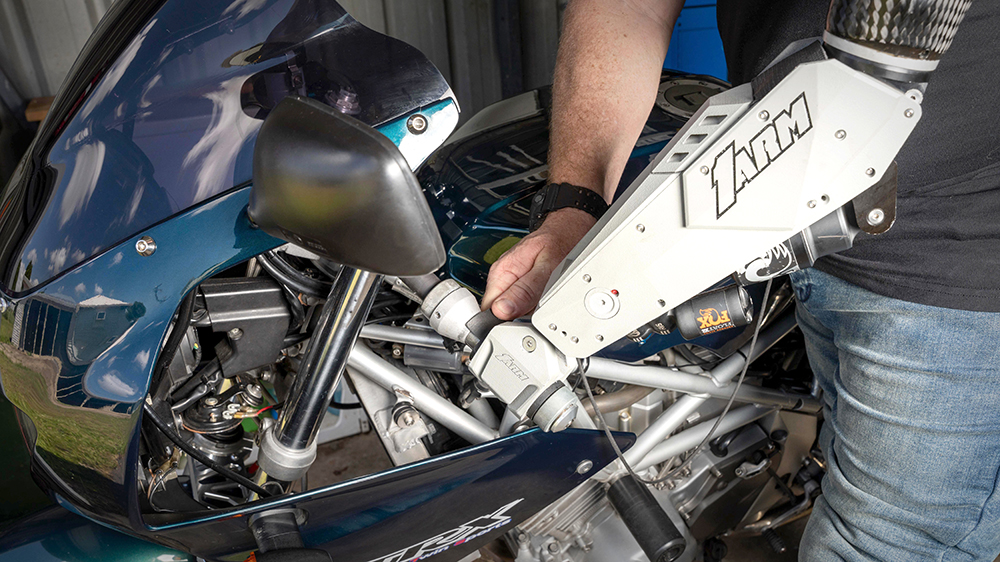

“There are no robotics or electronics in there because you’d have to have redundancies,” he explains. “It’s a mechanical thing, so as far as redundancies go, it just has to be able to let go at some point.”

That breaking point is equivalent of 50kg of grip strength because, as he points out: “if I need to hang on any longer than that, I should probably let go. There’s a safety tether, that’s a clip. So the hand is held in place by some cones, and this clip stops those cones moving away from the hand – if you really yank on the hand, it’s gonna push this clip up to what I call the release cone, so eventually it’s going to let go, but I have some control over it with the tether.

“The design process for the hand was actually the most complicated part – I’d have two dozen different hand designs – I didn’t want too many moving parts. Putting an elbow in is a piece of cake. The arm itself has a little bit past 90 degrees range of movement, which is what I wanted. The standard arm you can buy only gives you about 40 degrees.”

The elbow mechanism is actuated by a Fox mountain bike shock, whose high- and low-speed adjustment allows Shane to dial in a setup suited to the kind of riding he’s up for. It’s been custom tuned by Mountain Bike Suspension Centre which has resulted in a really natural movement.

“There’s no jerkiness, it’s beautiful,” he says. “The arm, the wrist and the elbow need to be loose, but it can’t be loose. So you need to dial the shock in for what you’re doing. There’s settings for one bike and settings for other bikes, but I generally just run it for the faster bike and push more with the others – imagine the inside of your elbow pushing forward. So when you’re coming into a corner on the brakes, that’s what I’m doing, I’m pushing forward from the inside of my elbow, and that stops the arm folding up. And then you push down on it to lean into a corner, to bend your arm.

“I have good control over it, and I have good feedback. There’s enough input here on my shoulder to know exactly what to do.”

Now on the third version of his motorcycle-riding arm, Shane says if he was to replicate another one today it’d cost him $13,000. The forearm section he’s responsible for is made up of an aluminium frame with fibre-reinforced nylon ‘bodywork’ and, between it and the shock, accounts for about $5000 of the arm’s cost. The upper section, which is made by a specialist prosthetics guy, is produced using eight layers of carbon-fibre and costs somewhere in the region of $8k.

Would he make one for someone else?

“Absolutely, but it’d cost more than 13 grand,” he grins.

But regardless of the cost, Shane achieved what he set out to do by going for another ride with not only his dad, but also with the son he very nearly didn’t meet as a result of what he now refers to as ‘didn’t-die day.’

“It was three generations out on the road. And it was very cool.”