Royal Enfield motorcycles have been scaling Himalayan mountain roads and trails for decades. However back in 2016, the Indian manufacturer released its first all-new mountain-conquering adventure bike designed and built entirely in-house.

The Himalayan 410 was a bike built to do a job and that job was to carry adventurers to places near and far, high and low. It didn’t do it fast, because it didn’t need to, it just had to be a loyal mule to its rider. People fell in love with the Himalayan and its simple practicality. Now, seven years later, I’m in the foothills of the iconic mountains in northern India to see if I, too, will fall for the latest Himalayan in Royal Enfield’s line-up.

The paint had barely dried on the 2016 model when the team of designers at Royal Enfield set about improving the Himalayan without ruining its quirky personality or risking its legendary reliability. As simple as the Himalayan was, this was no easy task. The first piece of the puzzle was a new engine, which was fitted into discreet-looking Himalayan test mules which racked up thousands of kilometres while hidden in plain sight.

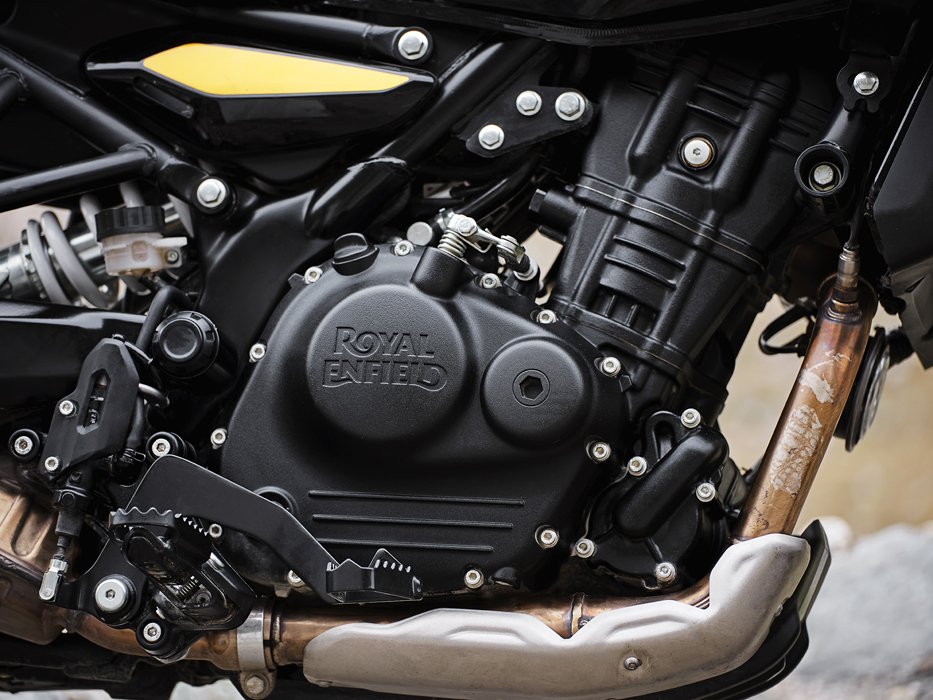

The new engine would be called the Sherpa 450, a nod to the job it would have ahead of it.

A complete step into the future for Royal Enfield, the Sherpa 450 is the first water-cooled engine to roll off the brand’s production line and a real boost in technology for the company. It features a four-valve head, dual overhead cams and a short-stroke design that allows the 452cc single to rev all the way to 9000rpm while hitting max power of 29.4kW at 8000rpm (compared to 18kW of the long-stroke 410).

Of course, horsepower wasn’t the only increase, the torque peaks at 40Nm at 5500rpm, which is 22 percent higher at 5000rpm and a hefty 68 percent more at 7000rpm over the outgoing air-cooled donk’s 32Nm capability. These output increases are also partly thanks to a higher compression ratio and you can feel the improvements right through the rev range – 90 percent of the torque is available at just 3000rpm.

The 452cc engine also received a slip-and-assist clutch and an extra cog inside the gearbox bringing it up to, well, speed with the rest of the world so there’s now six gears to choose from. Each gear ratio has been carefully selected to get the most out of the new engine.

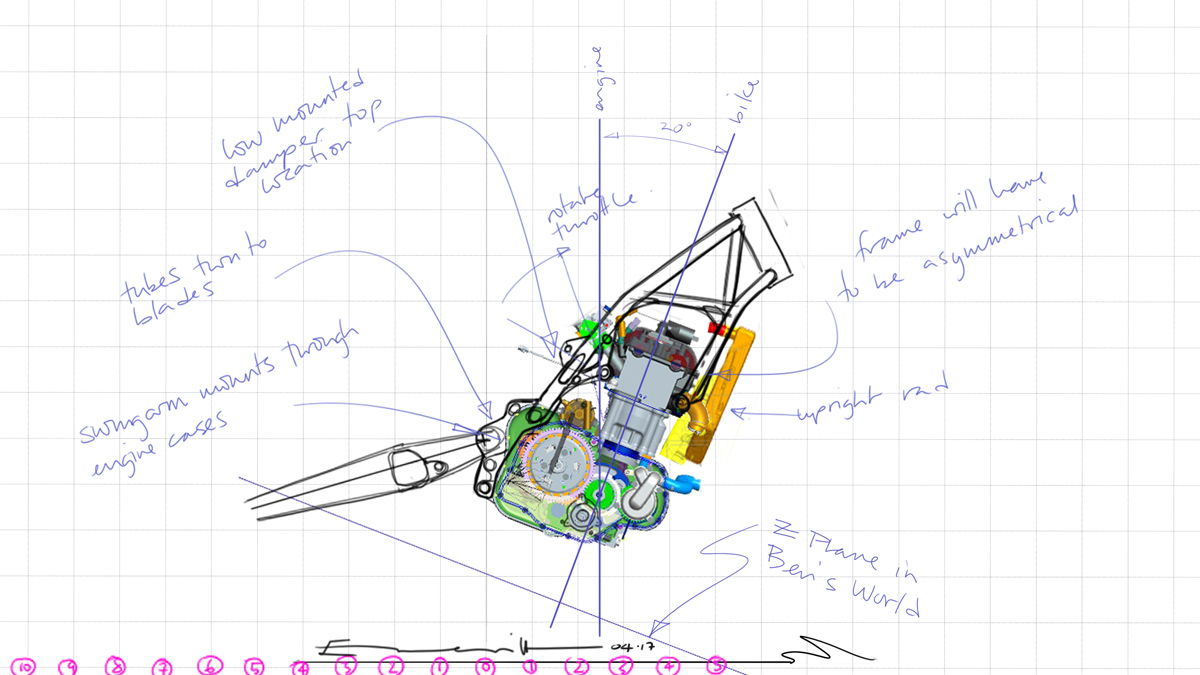

The designers also put bulk development into the new chassis. With the aim of keeping the centre of gravity low for maximum low-speed stability, the engine is a stressed member of the new frame and is inclined forward to maximise available space.

The rear subframe is a bolt-on affair to reduce the chances of irreparable damage occurring to the bike in a typical adventure ride fallover crash. It features a strong-looking rear rack behind the pillion seat to mount luggage to. Up front, the ability to carry luggage off the sides of the fuel tank is retained by a sturdy crash bar that serves double duty. I’d like to say I didn’t test the crash bars, but I did take a small tumble while farting about on an icy section of gravel road. The crash bars did their job, the day was not ruined, and I carried on riding.

While redesigning the Himalayan, some time was taken to iron out a couple of issues with the old bike. Notably the air intake was moved from under the seat up to the top of the engine behind the head stem. This keeps the airbox cleaner and farther away from water and mud during water crossings. It also sounds a bit throatier through the upwards angled throttle body, which is now controlled by a fly-by-wire throttle, which facilitates two ride modes in Sport and Eco (see sidebar).

The fuel tank is both two-litres larger and now mounted lower for improved centre of gravity and more compact packaging, the same reason a lay-down rear shock and compact linkage system was introduced for the rear suspension. And the catalytic converter and boom box has also been fitted down low behind the gearbox area, allowing for a much smaller silencer to be used while still meeting strict emissions requirements.

The 452cc engine is well muffled with this set-up, so don’t expect too many pedestrians to hear you coming. All this shuffling of weight also allows the seat height to remain quite low at 825mm, meaning the hugely accessible seat height of the original bike has been retained – fun-sized people (like me) rejoice! – but the standard seat is height adjustable to 845mm, so no one misses out.

The front suspension has had a massive overhaul to an upside-down separate-function Showa fork enabling 200mm of wheel travel. Rather than fussing about trying to perfect its own suspension, RE enlisted the help of Showa to build what they build best. The new fork is responsible for the smooth, controlled and precise feeling from the front-end. While the suspension can only be adjusted for rear preload via a c-spanner found in the on-board toolkit, I found the suspension to be a bloody good compromise for my 100kg-ish weight.

I didn’t get to test the Himalayan loaded up with luggage and/or a pillion, but I reckon I would probably be looking for a stiffer rear spring if I was planning to spend more time loaded than unloaded.

The wheels also copped a nice upgrade, despite retaining the 21-inch front and 17-inch rear wheel sizes. If you opt for the premium Kamet white model, this snow-camo-inspired version comes with a set of tubeless spoked wheels that look really good. The rest of the models come with regular tube-type spoked wheels. Tubeless is a no brainer for me as they are easier to repair and fewer spares need to be carried on big trips, plus they look a bit stronger too.

The brakes are Bybre-branded items with a two-piston caliper grabbing a single disc up front and a single-piston caliper at the rear.

They perform better than I expected. I was happy enough with my usual two-finger style on the road and one-finger style on the dirt. There is enough power and bite to bring the front ABS on during heavy braking on the bitumen if you get too frisky with them, while they are still gentle enough on the dirt not to upset the bike.

The ABS is a two-mode deal, with off-road mode slowing the intervention on the front wheel and turning off the ABS on the rear altogether. Road is regular ABS and both wheels on. To select the off-road ABS you do need to be stopped.

So how do all these improvements go out in them there mountains? Honestly, much better than I ever expected. Thankfully, our two days of testing did not involve any chaotic city riding. A short sprint up the mountain and through a 9km-long tunnel saw us emerge into the Himalayan mountains ready to explore. Between dodging cows, dogs and slow vehicles getting to grips with the new Himalayan was an absolute breeze.

With our phones paired up to the fancy new Tripper dash (see sidebar) where our route was clearly displayed, it wasn’t long before Taylor Swift’s Love Story started to play through my Cardo. The bike just simply works well. The engine is very smooth for a single cylinder without vibrations killing the mood, the brakes work with little effort and the gears click through nicely. Besides reminding myself to slow down and take it all in, I didn’t have to think or second guess what the bike was going to do around the next corner; it just felt so planted and predictable.

Obviously being a smaller engine, when moving off from a standstill you need to dial a few revs up to get going, but once the clutch is out, the engine revs effortlessly all the way to the 9000rpm rev limiter. It certainly feels fast enough to slice through the endless stream of slow trucks and slow cars found in India. I dream to try it at sea-level, or close to it, as I was told by the RE engineers that I was missing 30 percent of the power due to the altitude. I want to see how it goes in the Sydney traffic light GP!

A cruising speed of 130km/h was achieved with little fuss out on the flowing sections of the mountain roads, so the RE’s ability to tour in Australia shouldn’t be doubted at this stage.

While the Himalayan handles very well, one of the bike’s very few weaknesses – if you could even call it that – would probably be the CEAT Gripp tyres. While I was able to scrape the footpegs through the corners, I did find the limit of the tyres a few times on the bitumen. To be fair, the weather was quite cool and road conditions in the Himalayas are rarely the same from one corner to the next. But I would probably opt for a tyre more suited to my riding style.

The suspension did a really good job at dealing with all sorts of abuse from me. Yes, I could make the fork bottom out under brakes, but only if I was stabbing at the brakes rather than squeezing them.

The Himalayan took it all in its stride once the bitumen ended. I could ride along at a decent pace getting air off small jumps and undulations on the trail; if you get a bit overconfident, you will bottom the suspension out, but it’s not a hard bottom-out thanks to the hydraulic bump stop in the Showa fork. The 21-inch front wheel keeps the bike going in the desired direction even when things get a bit rocky. As a budget compromise – and let’s face it, everything on this bike is a compromise – the suspension is bloody hard to fault. You can tell Royal Enfield has put significant effort into developing the Himalayan’s off-road manners.

Comfort-wise, the Himalayan cannot be faulted. I started off the ride with the seat in the low position, but at the first stop I lifted it to the higher setting. I could still touch two feet on the ground but my knees weren’t folded as much.

The seat itself is comfortable and Royal Enfield quotes a fuel range of 450km, which I think would be a reasonable achievement in one sitting. With the lack of cruise control, your hand would require a rest before your bottom would. The somewhat small windscreen does a bang-up job of keeping the wind off your chest and face, but it wouldn’t shield you from any sort of weather.

You would think that with all this added tech and features the weight would increase, but it’s actually lighter than the old Himalayan, and with extra power, the bang for buck is strong. There is a certain feeling you get when you don’t have to think about what mode you’re in, what traction control and wheelie settings you have selected, and so on. On the Himalayan you’re able to just get in the zone and enjoy the bike for what it is designed for, exploring. And I can’t wait to explore some of Australia on one.

Test David Watt + Photography Mat Hayman & Tom Fossati