Ken Blake, Tony Hatton, Graeme Crosby, Roger Heyes, Jim Budd, Dennis Neill, Garry Thomas and Mick Cole count among the elite production racers of the 1970s. But one name that needs to be added to that top echelon of big-bore runners is Roy Denison, the popular St George MCC member who plied his trade aboard a private Honda CB750 and Kawasaki 900s/1000s in both Production and Improved Touring events.

Fellow St George member Lee Roebuck remembers Roy as a great bloke who was widely respected in the paddock for his knowledge and generosity. “Roy was as fast and aggressive as any rider in Australia,” Roebuck says.

He didn’t win many of the big-name events as a privateer, but ‘Roy the Boy’ was always there or thereabouts. His best result was second in the inaugural Arai Three-Hour at Bathurst behind Tony Hatton. His career, however, came to a shuddering end the following day when he crashed at the Dipper on the first lap of the fabled Unlimited Production race that saw Hatton edge out Garry Thomas’ Kawasaki Z1300. Denison was flung over the concrete wall and down the hill. He faced 18 months of gruelling rehab before he recovered, though not enough to race again.

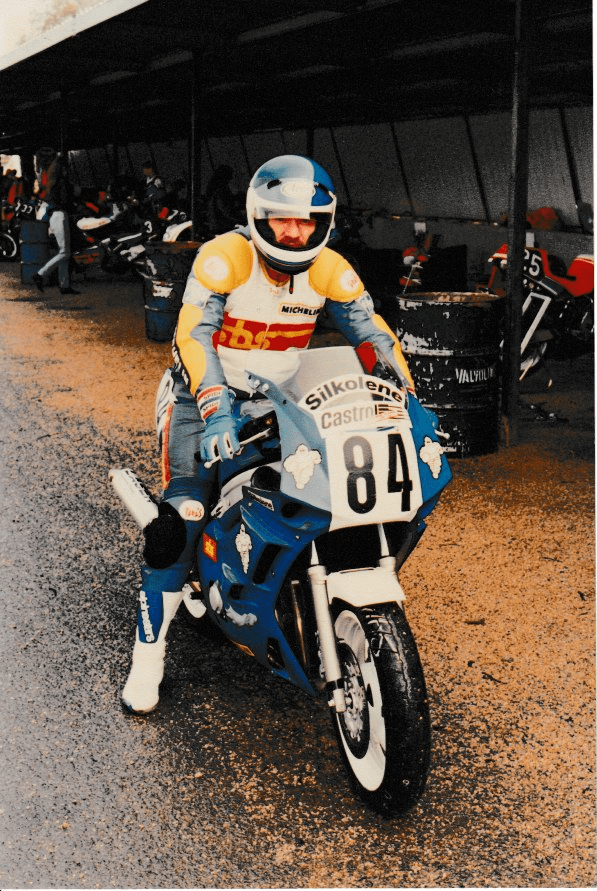

Denison turned his hand successfully to Formula Ford racing. He also set up a race school with Dennis Neill and later owned and managed the Michelin SuperStreet team as NSW distributor of the popular French hoops.

Team rider Ken Watson remembers the first day he met Roy. “I turned up to do some tyre testing for Roy on my raggedy RGV250 with patchwork panels. Roy consequently wasn’t paying too much attention to me. I went out in the concrete dust on some Michelin Hi-Sports, did a stint and came back in. Roy said, ‘Were you trying out there?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, I suppose’, although I went all-out to impress him. Roy said, ‘You just went under the 250 proddy record by a second.’

“He asked me who owned my bike, my gear and who bought my tyres – I told him that I paid for everything. By the end of the day he had come up with a new Yamaha FZR600, a $10,000 parts budget and a deal with Shoei Japan. That was the sort of bloke Roy was.”

Denison and Watson achieved great success in SuperStreet racing in the early 90s through a very simple formula. “Roy always said to forget about how the bike felt, it was all about lap times. Some people work on feel first then chase times. Forgetting about feel made you just ride the bike as well as you could without worrying about everything it did. Roy also banned steering dampers from all of our bikes because he believed that there was something wrong with the basic set-up or the rider if you needed one.”

By this time, Denison had been diagnosed with prostate cancer. It eventually spread to his neck, but didn’t dampen his spirit or sense of humour.

“Roy and I were practical jokers. He loved a laugh. He even made a comeback at Mallala in 1992 when he was sick. He qualified fifth, which was amazing. I remember a bloke said to him, ‘Hey, you go pretty good for an old bloke’. Roy felt slighted and told him where to go!”

Towards the end, cancer had eaten away the vertebrae in his neck and surgeons were forced to insert metal plates to support his head. “Roy told me that the doctors said if he made a sudden movement, he would die.” It was a terrible final chapter to a big life. “I saw Roy the day before he passed away. It was very difficult, but his sense of humour was as sharp as ever.”

Roy’s greatest legacy as motorcycle manager for the NSW MTA will be his role in the successful adoption of the LAMS scheme in the early ’90s. Denison and fellow LAMS advocate Steve Wiggins, representing the Federation of Motorcyclists, faced a mountain of opposition, but Roy played the political game tirelessly to see the NSW government eventually launch the scheme on a trial basis. Its ultimate success saw LAMS spread nationally and it’s now crucial to attracting new riders.

Roy Denison passed away on 28 February 1993. He was farewelled grandly at a funeral filled with racing royalty. Part of his eulogy read: “A special man, a brave man. Will always be admired and remembered.”

DARRYL FLACK