In seven decades of Grand Prix racing there’s never been a premier-class GP bike like the Suzuki RG500. Quite a statement, but based entirely on fact.

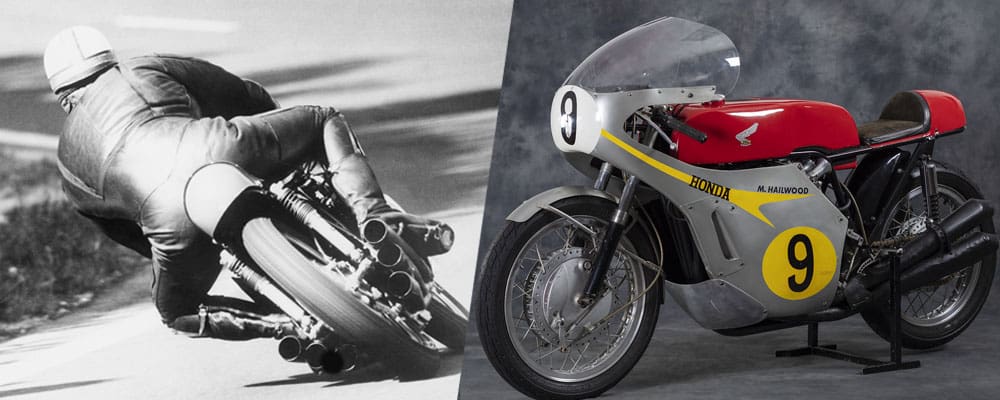

Factory and production RG500s scored 50 GP wins and dominated GP grids for years: in 1977 all but four of the 30 World Championship points scorers were on RGs, the following year it was all but six of 30 scorers and in ’79 all but seven of 35. No other 500 has a record like that, not even Norton’s venerable Manx or Honda’s fiery NSR500.

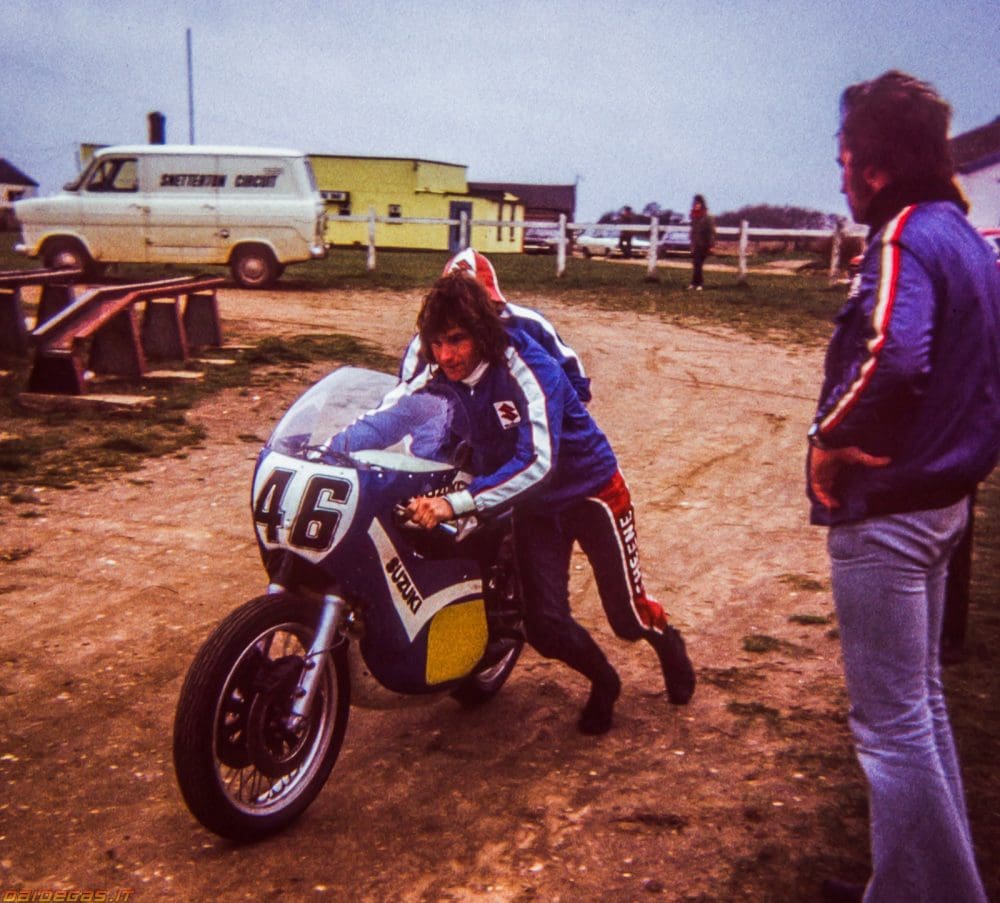

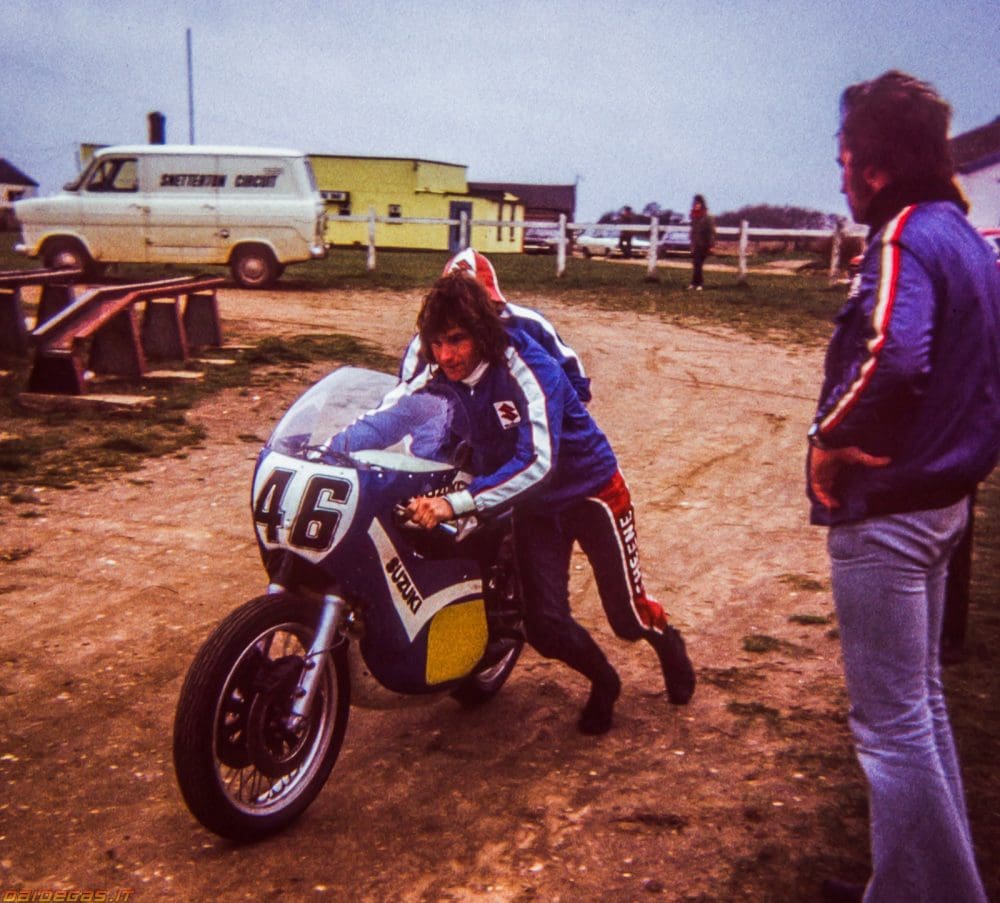

The bike scored its first GP podium in 1974 and its last in 1984. Amazingly, it was Barry Sheene – who became synonymous with the bike and vice-versa – who took both of those results, the first when he was a long-haired rookie full of life, the last when he was a gnarled veteran full of metal.

Factory RGs (or XRs, for Experimental Racer, to give them their proper name) took four 500 World Championships between 1976 and 1982, with Sheene, Marco Lucchinelli and Franco Uncini on board.

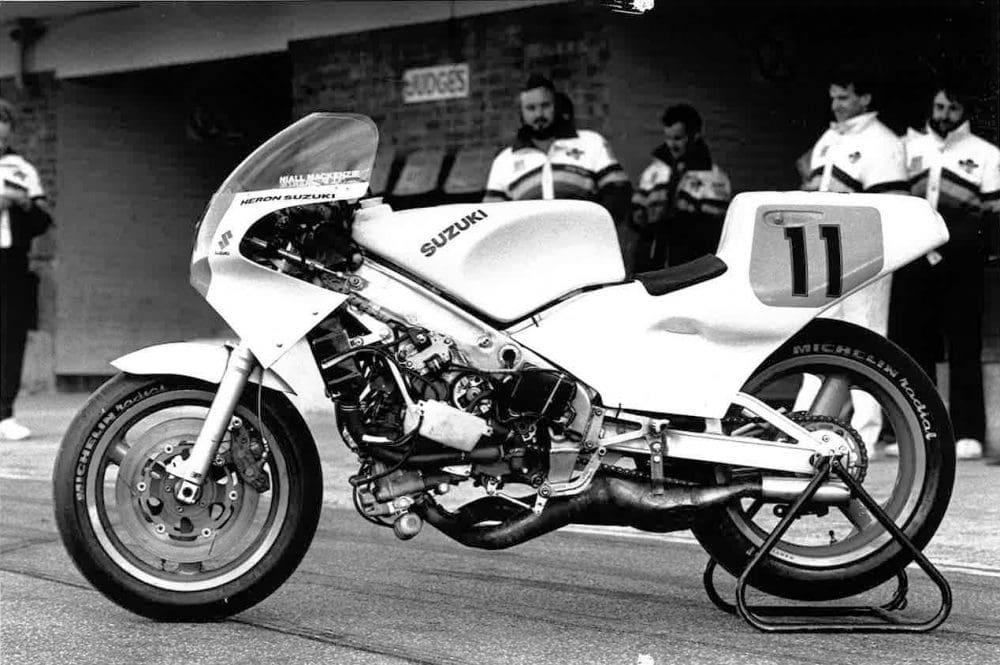

Their numerous GP wins include the fastest in history – Sheene’s 1977 Spa-Francorchamps win, achieved at a mind-boggling 136.8mph (220km/h) average. The bike scored its last front-row start at Misano in 1986 with Niall Mackenzie aboard. HRC warlord Youichi Oguma was so impressed that he visited the Suzuki GB awning (no full-factory effort by then) to present the team with a bottle of champagne.

And yet, you might argue the real glory of the RG (for Racer, Grand Prix) was in its production versions, which were the mainstay of 500 racing around the world for a decade, not only at GP level but also at national races and even club events. The last truly private motorcycle to win a premier-class Grand Prix was a Mark 6 production RG in the hands of Dutchman Jack Middleburg, who outfoxed Kenny Roberts to win at Silverstone in 1981.

As if all that wasn’t enough, the RG500 was the making of renowned MotoGP crew chief Jeremy Burgess. JB raced production RGs Down Under in the 1970s and his bike prep was so good that in 1980 it got him a job fettling Randy Mamola’s XRs. From there he went on to work with Freddie Spencer, Wayne Gardner, Mick Doohan and Valentino Rossi.

“The RG was an extraordinary motorcycle,” says JB. “And it was probably the forerunner of the modern-day 500 GP bike, up to and including the NSR500. The RG wasn’t a V4, it was a square four, but the idea was essentially the same – to place the cylinders more centrally than the inline fours did.”

The first RG – the XR14 – hit Europe in the spring of 1974. Sheene rode the bike to second place in its first GP at Clermont-Ferrand, just five seconds behind Phil Read’s MV, despite oiled plugs.

The next summer Sheene gave the bike its first victory at Assen, mere inches ahead of Giacomo Agostini’s Yamaha, and in 1976 he won the RG’s first world title. That same year Suzuki unleashed the first production RG. The bike made its race debut in Australia, where Agostini (now back with MV again) was planning to have a little off-season fun. Burgess recalls what happened next:

“Ago got bombarded with 15 of these bikes he’d never seen before, he got taken to the cleaners by a bunch of production two-strokes. He probably expected to come down to Australia, as he had in previous years, for a fairly leisurely time and a bit of easy money.”

If MV had harboured any hopes that the four-stroke’s time wasn’t yet over, that trip must’ve been a horrible shock.

Burgess took delivery of his RG a few months later. “When they first released the bike to the public it had aluminium disc brakes coated with a sort of steel plasma, an oil pump and no silencers,’ JB recalls. “Halfway through 1976 an updated model arrived with steel discs, silencers and no oil pump – that’s the one I got.

“The bike was fantastic to ride. I could only put it into context when I got rid of the RG and bought a TZ750 Yamaha. I thought the TZ would be better, but it didn’t have the same feeling – with the RG you felt you were sitting in the bike, with the 750 you were sitting on it.”

However, the RG’s performance did come at a price. “You really had to have a bit of an engineering brain, an understanding that maintenance was much more important than on the TZ350 I’d owned before,” Burgess adds. “If you didn’t enjoy mucking around with your bike when you unloaded it from the trailer, if you expected just to run it week after week, which you could do with the Yamaha, you’d end up with some expensive repair bills.

“There were a few weak spots, like you had to keep a constant eye for cracks on the rotary valves. It was frustrating when things broke, but I learned that if you can see the crack before something breaks, then the repair bill will be smaller. I won a couple of little races on the bike and enjoyed some good results, but more than anything the RG gave me a great feeling about racing. It was just a damn good bike.”

In 1980 Yamaha tried to muscle in on Suzuki’s success by producing a production version of Kenny Roberts’ inline four OW. The bike was a total failure.

“The production RG was light years ahead of everything else and it was probably the last great privateer’s bike,” says JB. “Guys were earning livings all over Europe on the things, and if you wanted to win your national championship, the RG was it.”

Burgess spent 1980, 1981 and 1982 working with Mamola, who twice finished championship runner-up on Texaco Heron Team Suzuki XRs. He has no doubt Mamola would have won the crown if he had had different tyres.

“Randy was the factory favourite to win the title, but he just needed Michelins instead of Dunlops, like Lucchinelli and Uncini.”

While working for Heron, JB was sent to the 1981 TT to look after Mick Grant’s RG500. What was that like?

“More welding! Everything breaks at the TT – it’s a pretty tough environment for a motorcycle. Things that won’t break at GPs break at the TT – you’d get cracks in the handlebars, silencer mounts, cowling mounts and so on.” No worries, with JB’s welding torch on hand, Granty won the Senior.

Having originally travelled to Europe for a holiday, with no plans to work, Burgess was blown away by his experiences of working on factory XRs.

“Being a young bloke in the thick of all that hi-tech equipment was like being a kid in a candy store.

“We had everything, titanium this, magnesium that. You end up becoming blasé about all this stuff and then you start putting titanium bolts in the awnings!”

Sheene and the Suzuki

Racing’s first rock star Barry Sheene and Suzuki’s RG500 go together like fish and chips. The relationship began in late 1973 when the great British hope travelled to Suzuki’s Ryuyo test track in Japan.

Sheene broke the circuit record by 1.5 seconds, but in spite of the bike’s awesome straight-line speed he didn’t fall in love with it because it was a pig to ride.

“That first RG I rode started running at nine grand,” said Sheene, speaking in 2002. “Below that there was nothing, and when I say nothing, I mean nothing. To get it out of the paddock you had to scream it at 10,000rpm or it wouldn’t even clear, and it stopped at ten-five, so once you’d got it clear at nine-five, you had 1000rpm to play with.

“I told them it was a waste of time unless they spread the powerband, but they were going: ‘but Barry-san, it’s got 105 horsepower!’

“Foolishly enough I told Suzuki I’d go to Japan at the end of ’74 and stay there until the engine was right. I was there for five weeks, the biggest jail sentence I’ve ever served in my life, a nightmare, but the bike came good.

“By ’79 the RG would start at seven five and go through to 11,000.

“It was just the extra knowledge they had about porting, expansion chambers, ignition timing, everything. And by ’86 or ’87 you could ride a 500 around town if you fitted low enough gearing, they were increasingly a lot easier to ride.”

Sheene took all but one of his 19 500 GP wins on XRs.

Developed to the bitter end

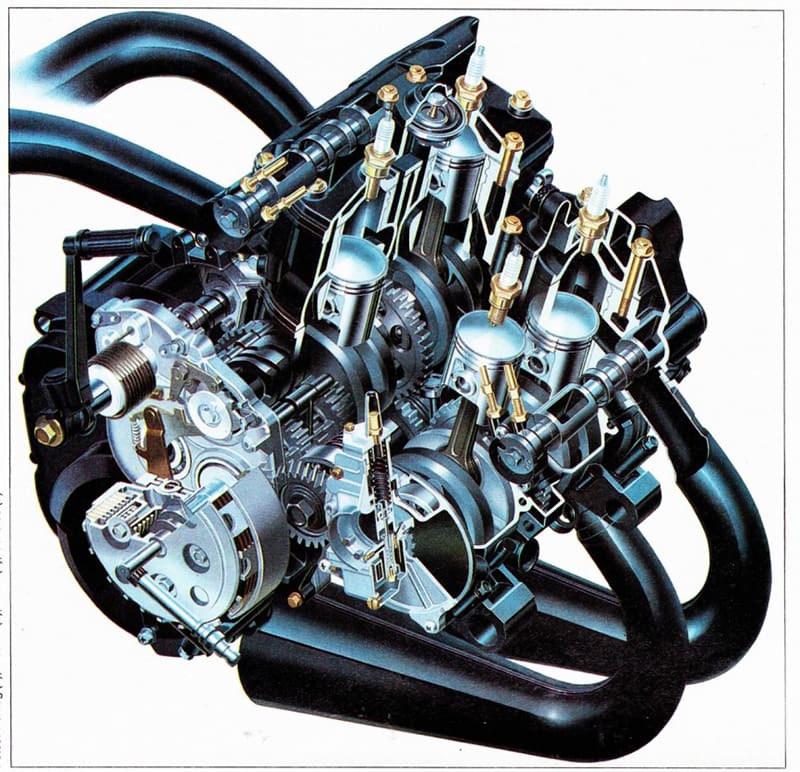

The RG500 may have changed substantially during its 11 years as a factory GP machine, but it remained essentially the same: four rotary valve 125cc top ends arranged in a square format. Or two tandem-twin MZ250s side-by-side, if you prefer.

Everyone knows Suzuki stole its two-stroke know-how from MZ genius Walter Kaaden, but there’s no doubt that with the RG they developed rotary valve technology about as far as it would go. The first XR14 made around 75kW, but that stunning performance came at a price. It seized regularly: pistons, cranks and gearboxes, throwing Sheene and others down the road with pitiless regularity. After all, this was an era when metallurgy struggled to keep up with engine performance, and if you wanted to ride the fastest bikes, these were the extra risks you had to take on board.

The XR14 didn’t handle well either – hardly surprising since the frame wasn’t a full cradle. Development was rapid, with mechanics jetting back to Japan with broken or under-performing parts in their suitcases and returning to Europe a few days later with redesigned parts. For 1975 a full cradle frame appeared with a beefier, square section swingarm and laydown shocks.

For 1976 the bore and stroke changed from 56 x 50.5 to 54 x 54 and the bike was fast and reliable, so Sheene was unstoppable. He retained the crown in 1977. Once Randy Mamola became Suzuki’s number one the factory worked hard to create an even smaller motorcycle and they achieved that aim with the XR34 of 1980. In search of more rpm, Suzuki reverted to the original 56 x 50.5 bore and stroke for 1982 (when the RG won its last world title). The result would almost certainly have been different if Roberts’ OW61 hadn’t been such a disaster and if Honda hadn’t been busy developing its very first two-stroke GP bike, the reed-valve NS500.

Suzuki withdrew its factory team at the end of 1983, confident the RG was fully past its sell-by date. But Suzuki GB soldiered on for several more years. It’s significant that Sheene achieved the bike’s final podium at a soaking wet Kyalami in March 1984, when big balls rather than cutting-edge technology mattered most.