Twenty five years ago, Australian motorsport lost a legend when Gregg Hansford, the only racer to win Bathurst on two and four wheels, died in a Super Touring Car crash at Phillip Island. It was a blow that is still felt by friends and fans across Australia.

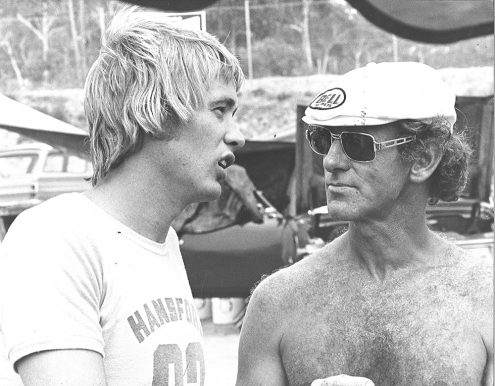

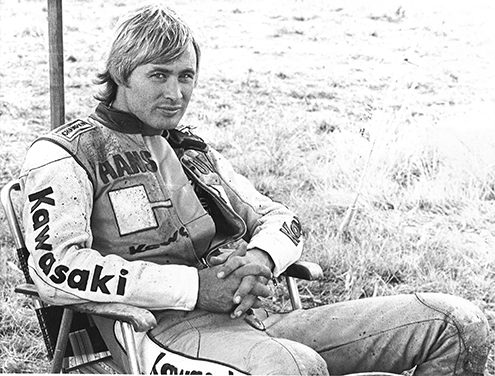

Gregg Hansford epitomised the Aussie sportsman of the 70s. While modest by nature, he feared no one, was blessed with natural talent, and had all the accoutrements of a superstar in that era: the flash car, the jet ski, long blond hair, a gold chain and medallion, big sunglasses, white flared jeans and a Golden Breed surfwear sponsorship. Those were halcyon days, when people could make a good living out of motorcycle racing in Australia and even head overseas to take on the world’s best in the US and Europe – all to a soundtrack of Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd on the eight-track tape deck in a Ford GTHO between meetings.

Gregg Hansford took his talent to the world stage in the late 70s and still ranks as one of the best racers never to have won a World Championship. Sadly, his grand prix career was brief and ended prematurely. Barely recovered from a monster crash at Imola, Italy, he returned to the track at Spa, Belgium, in 1981, and suffered a serious accident. His front wheel had been changed, requiring the brake lever to be pumped several times to get the pads working properly. But this wasn’t done and he rode off the track, hitting a parked car. Then, on the flight back to Australia, he suffered a blood clot and nearly died from the after-effects.

Unable to ride competitively again, Gregg Hansford switched to touring cars and a second career of racing that ended in tragedy at Phillip Island on March 5, 1995, when his Ford spun and was hit by another car. As the tributes flooded in, one of his GP rivals, “King” Kenny Roberts, ranked his ability second only to 1985’s dual World Champion Freddie Spencer.

We spoke to a cross-section of friends and competitors to get a snapshot of the racer and the man.

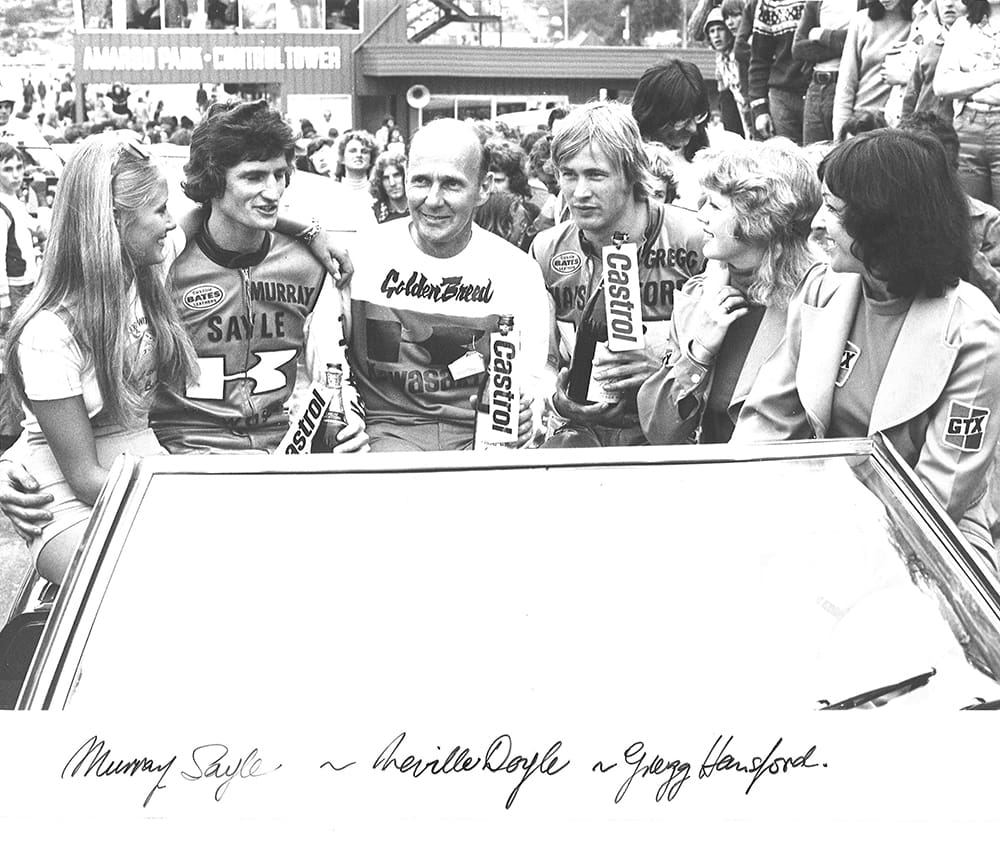

Murray Sayle

Gregg Hansford is remembered for some epic clashes with Warren Willing in the mid-70s, but the man who raced him most was his teammate Murray Sayle. The pair won 29 races from 31 starts in 1975 plus the Castrol Six Hour classic, an incredible effort riding air-cooled Kawasakis against liquid-cooled Suzukis and Yamahas. Because Team Kawasaki Australia was funded by state distributors there was an obligation to race at circuits as far away as Perth and Adelaide, so they were on the road a lot together.

“I’d seen a lot of Gregg before he joined Team Kawasaki Australia at the end of 1974. In fact I watched him compete at perhaps his first road race, at Lakeside on an ex-dirt-track Kawasaki Centurion 100.

“In 1972, Gregg, Warren Willing and I were given special dispensation as B-graders to race in the main event against the great Ago [Giacomo Agostini, 15 world titles] at Oran Park. It was a sign of the times that the younger guys were the equal of the older riders – the generational change was being recognised.

“I often raced against Gregg and I never went into an event thinking he was unbeatable. The difference in our styles was that he carried a lot of mid-corner speed whereas I tended to stop and fire the bike out of corners. He was one of the hard-braking riders and that skill meant that when he went to Europe he was able to keep up with riders like Kenny Roberts and Kork Ballington on the Kawasaki KR250.

“The years 1974 and 1975 were a very interesting period where the Kawasakis went from Dunlop treaded tyres – which would wheel spin when you applied full power – to American slicks. At the end of 1974 we moved to Goodyear slicks and used these in 1975. Our air-cooled H2Rs were not so much developed in great leaps but micro-steps by TKA over three years. The narrow powerband was tuned to get drive from 3000rpm and serious power from 5000rpm to 9500rpm. We went from five-speed to six-speed gearboxes and bigger carbs in later years.

“When the water-cooled KR750 came along it wasn’t the game changer we thought it would be. Our old bike revved higher and came on much stronger in the midrange, but the narrower-engined KR750 handled better on the grippier tyres. The H2R was a littler wider and this became an issue on those tyres.

“In 1975 Gregg and I had bikes with similar performance but his was the latest version so was lighter and had magnesium wheels. We had some great races and in the early period there were still some push-starts that made it even more interesting. In particular I have fond memories of Lakeside and also Sandown, where I held the lap record despite not always getting the best of starts.

“It was a great year and we had a lot of adventures, such as the time we did a pre-Bathurst tour of rural NSW arranged by publicist John Smailes. Gregg and I toured the regional radio stations in his Ford GTHO Phase III, Australia’s fastest production four-door car.”

Peter Doyle

As a teenager, Peter Doyle went from sweeping the warehouse floor at Kawasaki Australia to becoming a mechanic for father Neville Doyle and Gregg Hansford on the GP circuit.

“Gregg was part of the Doyle family, really. I knew him long before I was a teenager and he and teammate Murray Sayle used to kick me around hotel rooms.

“The European experience was an eye-opener. There was Suzuki GB, the biggest team, Kenny Roberts’ team, and Stuart Shenton with Kork Ballington [Kawasaki]. They all had the big transporters. Then there was Gregg, my father Neville, stepmum Margo and myself at the 250cc and 350cc GPs, F750 and as many international events as we could to get the appearance money.

“Pressure never fazed Gregg. For example, he wasn’t on the FIM graded list for the 1978 West German Grand Prix on the old Nürburgring circuit. Eventually he was allowed to race but he’d missed all the practice sessions. Never mind. He ended up on pole with a time of 8m53.30s on this hugely demanding 22.8km circuit. He finished second in the race to Kork Ballington.

“We did a lot of behind-the-scenes work at the GPs. There was always the issue of inconsistent fuel at the various circuits. The bikes needed a lot of maintenance, such as a change of crankshaft every second race, and two sets of pistons per weekend. Sometimes you’d have just 90 minutes to rebuild a bike between practice sessions. But they were so easy to work on as they were true purpose-built factory racing two-strokes. Four springs held on each exhaust pipe, four bolts undid the rear end, rubbers held the petrol tank on, and two clamps secured the carbs. I could get the 250cc engine out in six minutes.

“Gregg was pretty laid-back through all of this. I remember one time having to run back to the motorhome to wake him up before the 1979 Le Mans GP, a race he had to win to win the championship. He set pole and came second in the race.

“Gregg was good at anything he wanted to do, whether it was golf, squash or surfing. Statistically, he was undoubtedly one of the best of his era. And this was despite giving away a 25kg weight penalty in the smaller classes. Things might have gone very differently if he’d taken up the offer from Yamaha for the 500cc class for the 1980 season.

“At Spa he got a blood clot in his leg flying home and it took 18 months to recover and see if he could even ride a roadbike again. However, car racing was always a passion for him so the switch wasn’t a huge jump.

“Gee, I still remember the day I got news that he had died at Phillip Island. I was near my apartment in Sydney when I got the call.”

Kork Ballington

Four-time GP World Champion Kork Ballington had some ding-dong battles with Gregg Hansford on his way to double victories in the 250cc and 350cc classes in 1978 and 1979. In the 1978 250cc title chase Gregg Hansford finished just six points behind Kork.

“I considered our team was state of the art with a big transporter and factory mechanics so it was a surprise to see Gregg there with Neville and his wife and son running three classes (250/350/F750).

“Gregg came into the 250cc season with a bike that was well set up and he basically blew me into the weeds in the first few GPs. He was running a well-sorted Goodyear front slick while we had a Dunlop that didn’t work. His bike was also quicker in a straight line, even considering his weight disadvantage.

“It was more of a level playing field in the 350cc class but he was a force to be reckoned with in those early races. He could learn a new track in a flash, but that’s not unusual for a top rider. My big issue was trying to outbrake him and match his corner speed.

“I rode harder than I knew I could to beat him for the first time that season at Mugello [Gregg Hansford had won the previous Spanish and French 250cc GPs]. We both broke the lap record by three seconds [set by Walter Villa’s factory Harley-Davidson] and it took another six years for my lap record to be broken. It was the most intense race I’ve ever had in the 250cc class. I was sliding all over the place.

“Gregg was a tough competitor but a really nice bloke. We raced hard and played hard. I remember after practice at the Nürburgring he called me over and told me he had a really nice drink that I should try. I looked at the bottle and it read Bundaberg OP. I should have smelt a rat – it was 100 octane rocket fuel.

“Another time we were on the overnight ferry to the GPs in Sweden and Finland. I was winning big time on the blackjack table and he was losing so he grabbed a handful of chips off me and proceeded to lose those too!

“We both had a true loyalty to Kawasaki and who knows what might have happened if he’d signed for Suzuki or Yamaha in 1980. I’ve still got Gregg’s H1RA 500cc triple. I was winning the South African title on this model while he was winning the Australian title on his, so it’s nice to own it for these two reasons.”

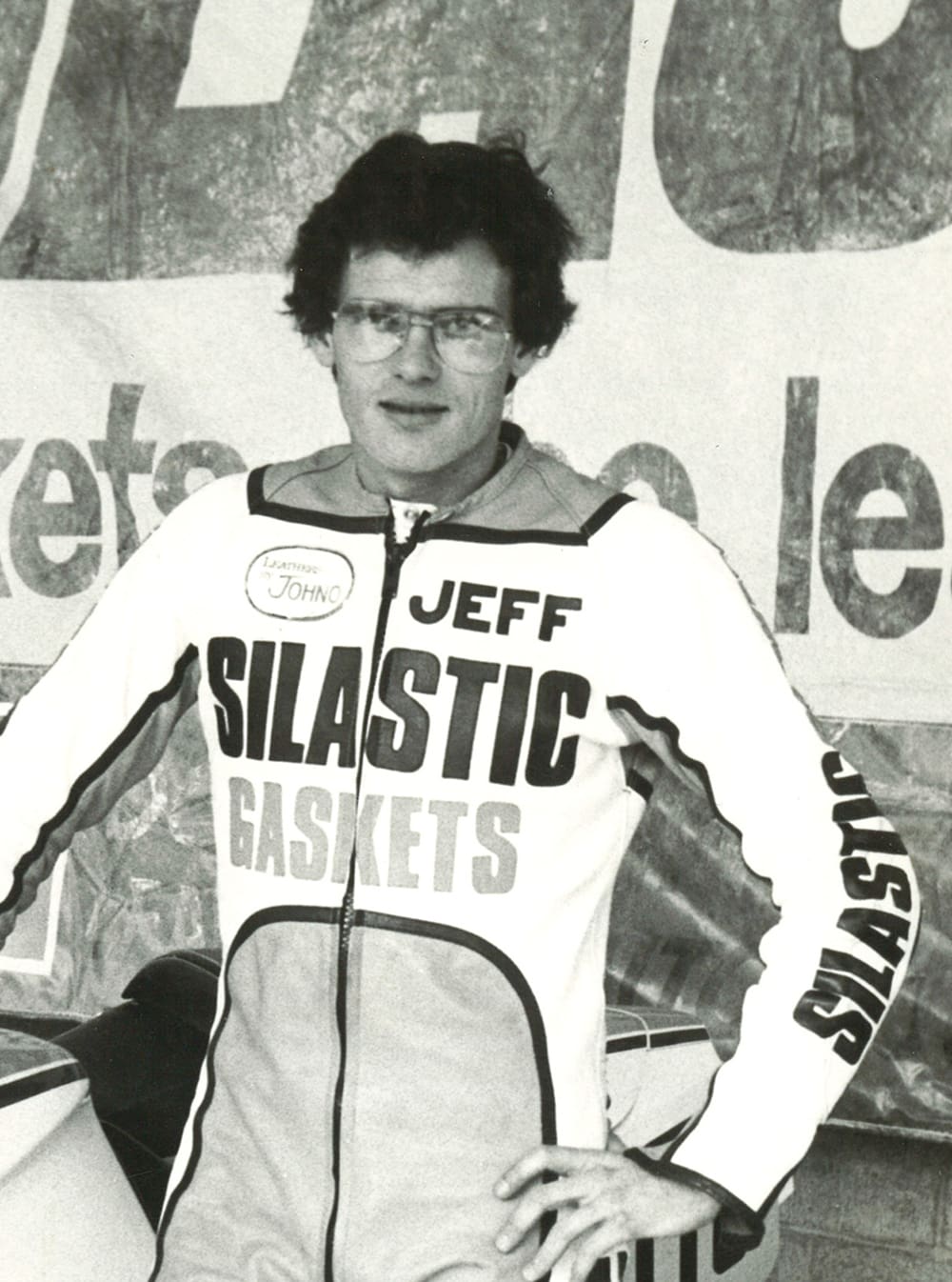

Jeff Sayle

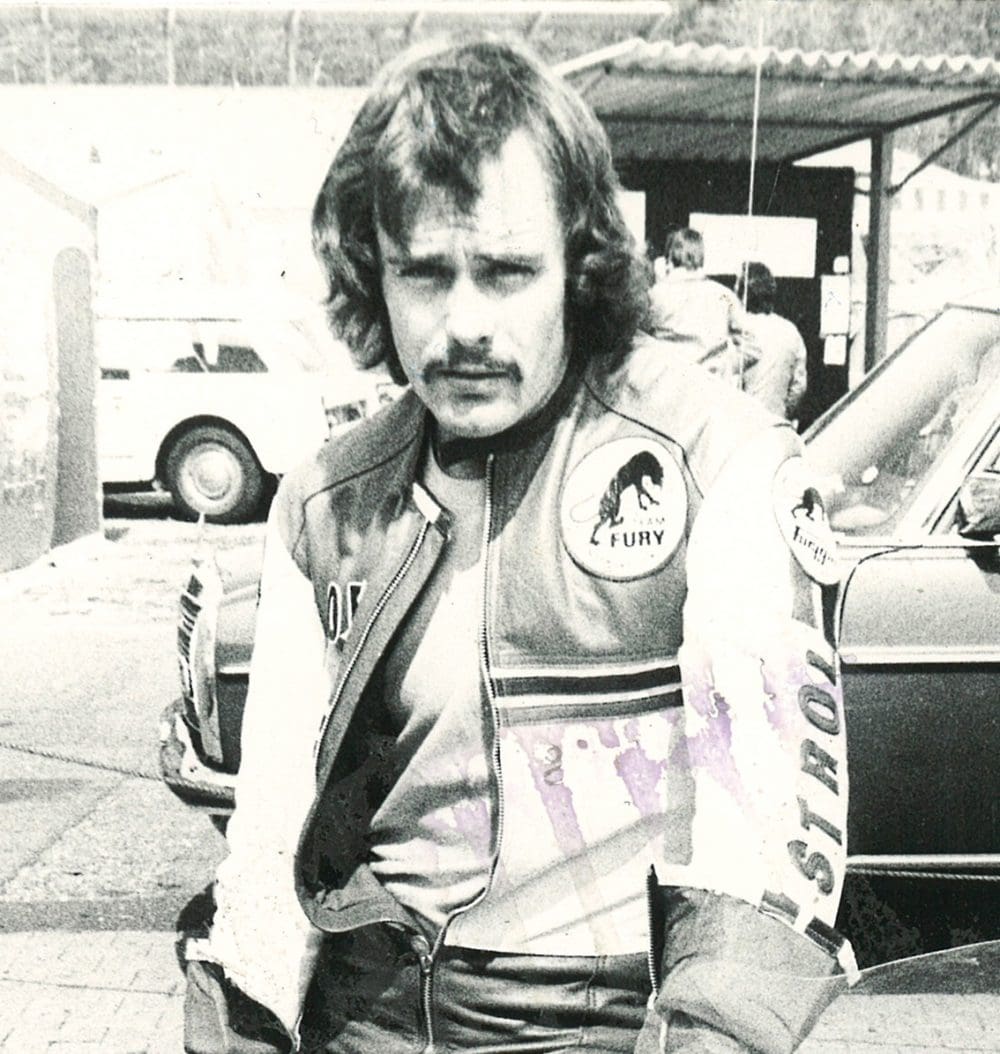

One of the wave of Australian privateers to go GP racing in the early 80s, Jeff Sayle developed a special bond with Gregg Hansford.

“I was a bit younger than Gregg and his contemporaries but we became good friends and that continued long after we finished racing. Gregg got me sponsorship with Donny Pask, which set me on my way. He was a great bloke who was always there to help me out and give good advice.

“He was the yardstick by which we judged ourselves. When Warren Willing and Gregg went to race in the US we could see they were competitive and it made us try harder. Their efforts gave us the chance to compare our talents at a world level. The 70s were amazing. You could buy a TZ350 for $2000 and pay it off with prize money within six months.

“Warren went to Europe first but when Gregg went over in 1978 he also made the minds up for a lot of us to go. His one downfall in grand prix racing was that he didn’t like living in Europe.

“Everybody drifts apart in their lives. You may keep in touch through things like Facebook but very few people have more than one or two lifelong friends. Gregg was my lifelong friend. I last saw him at Eastern Creek not long before he got killed at Phillip Island. I still miss him.”

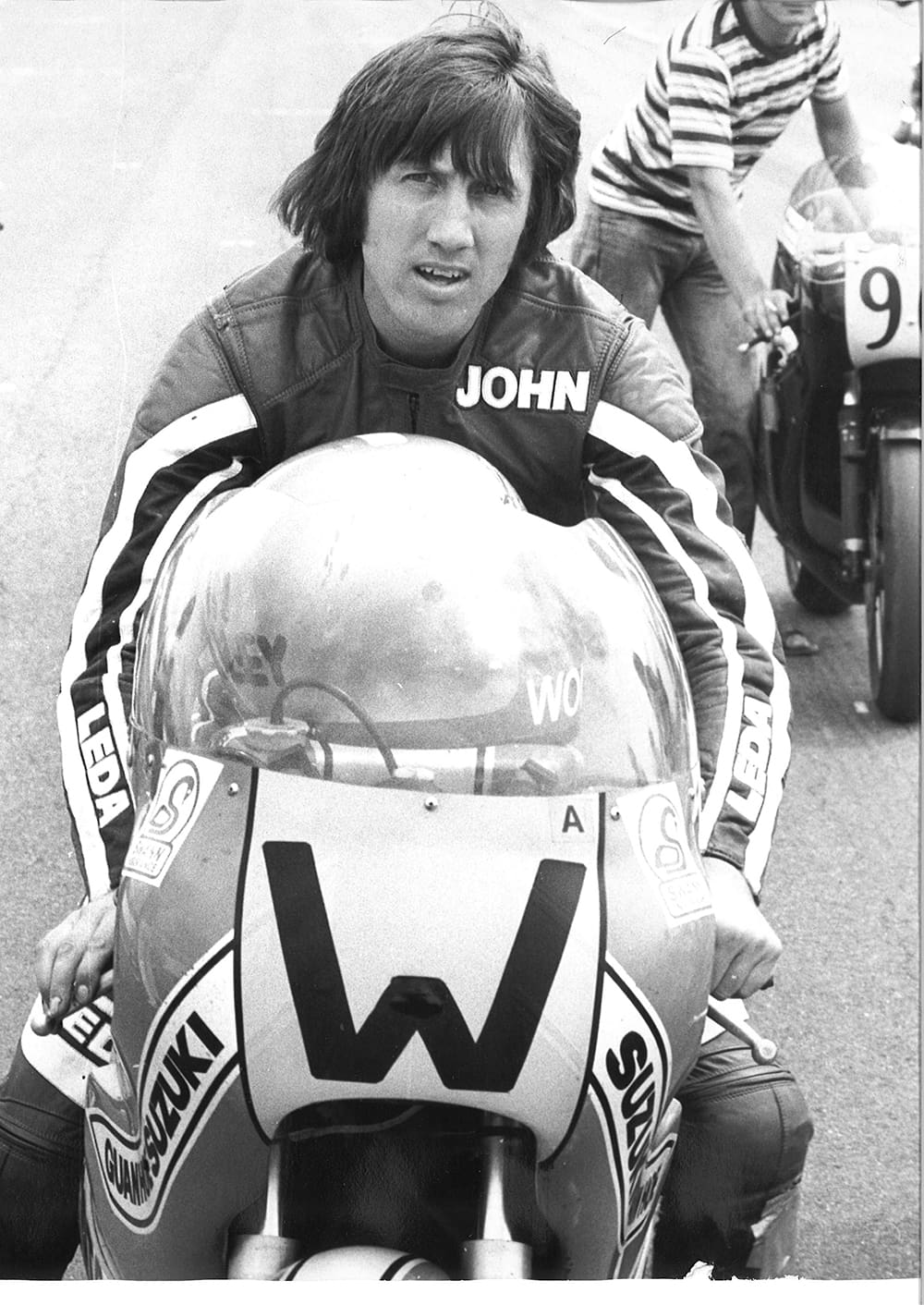

John Woodley

Kiwi hotshot John Woodley stormed to many victories in Australia in the 70s on RG500 Suzukis. He won Bathurst’s Senior Grand Prix in 1976, ’77 and ’79.

“I rate Gregg Hansford in the top three in the world for my era of racing, along with Kenny Roberts and Pat Hennen. He was a very unpretentious but great racer and I consider it a tremendous honour to have raced against him. I always had to think about the strategy required to beat him. I gave no quarter in our battles but he always found a higher level of skill to do the job.

“One of the absolute highlights of my career was the time I spent in Australia racing against Warren Willing and Gregg. Warren was a brilliant and calculating, measured rider. While Gregg was also calculating he could really dig deep spontaneously to win.

“No disrespect to Neville Doyle, who prepared his 750cc Kawasaki beautifully, but I think my RG500 Suzuki was more rideable on tight tracks like Oran Park and Amaroo Park. It was nearly always Gregg’s riding skill that won the day.

“I saw enough of Gregg riding the 250cc Kawasaki in Europe to see his talent shine. His size was a distinct disadvantage but he had a huge heart and he handed out plenty of riding lessons around the world.”

Jeremy Burgess

Legendary MotoGP crew chief “JB” spent most of the 70s as a privateer road racer.

“I raced against Gregg many times in the 70s but it’s probably more truthful to say I was in the same race rather than actually challenging him. His talent was obviously enormous but he also had a big heart that won him many supporters. For example, UK fans have fond memories of him when he fell off in an F750 race, picked up the Kawasaki, restarted it and finished fourth. In those days in the UK, if you crashed you usually stayed on the ground and retired.”

Paul Cawthorne

Team Kawasaki Australia boss Neville Doyle loaned Gregg Hansford’s KR250 and KR350 to racer Paul Cawthorne in late 1979.

“Gregg used to stay at my house when he raced in Adelaide. He was never a big mouth; in a race he just used to get on his bike and ride away from everyone.

“I remember once we were all racing in Tasmania in the wet and Gregg was easily the fastest. When I came back in and sat down he looked at me and said: ‘What’s the problem?’ I said ‘I can’t do it; things just aren’t clicking for me.’

“He said: ‘Slow down; put some ear plugs in so you can listen to what the engine is doing.’ I went out and shaved four seconds off my lap times.

“When Gregg was flown back from Europe after his crash he was very sick with a blood clot. I travelled from Adelaide to his Brisbane hospital to visit him. He was lucky to survive that.”