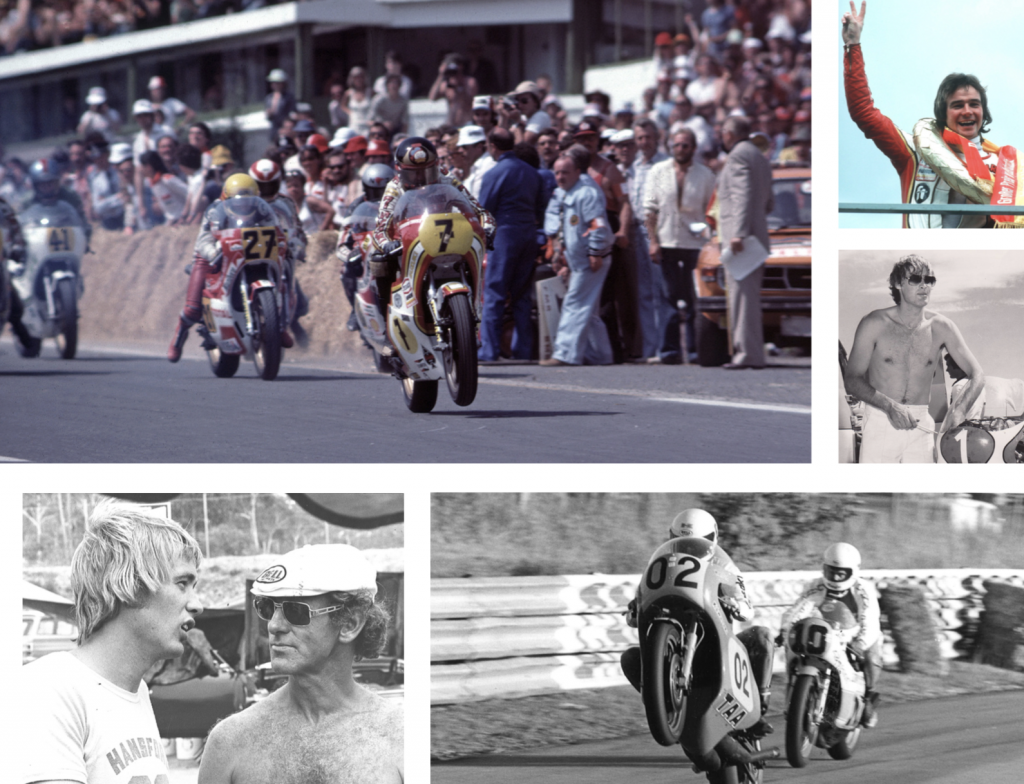

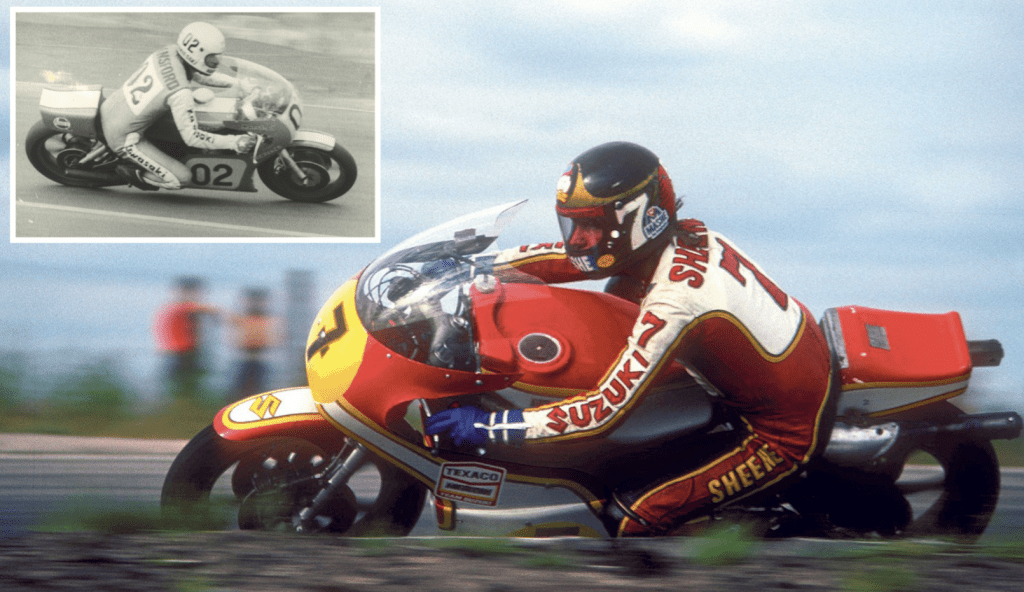

The biggest change in the history of road racing? Surely it was in the 70s, when the sight of pudding basin helmets and black leathers worn by stern-faced men was replaced by brightly coloured race suits, umbrella chicks, and decaled full-face lids worn by hard-partying blokes who could pass as either rock stars or surfers.

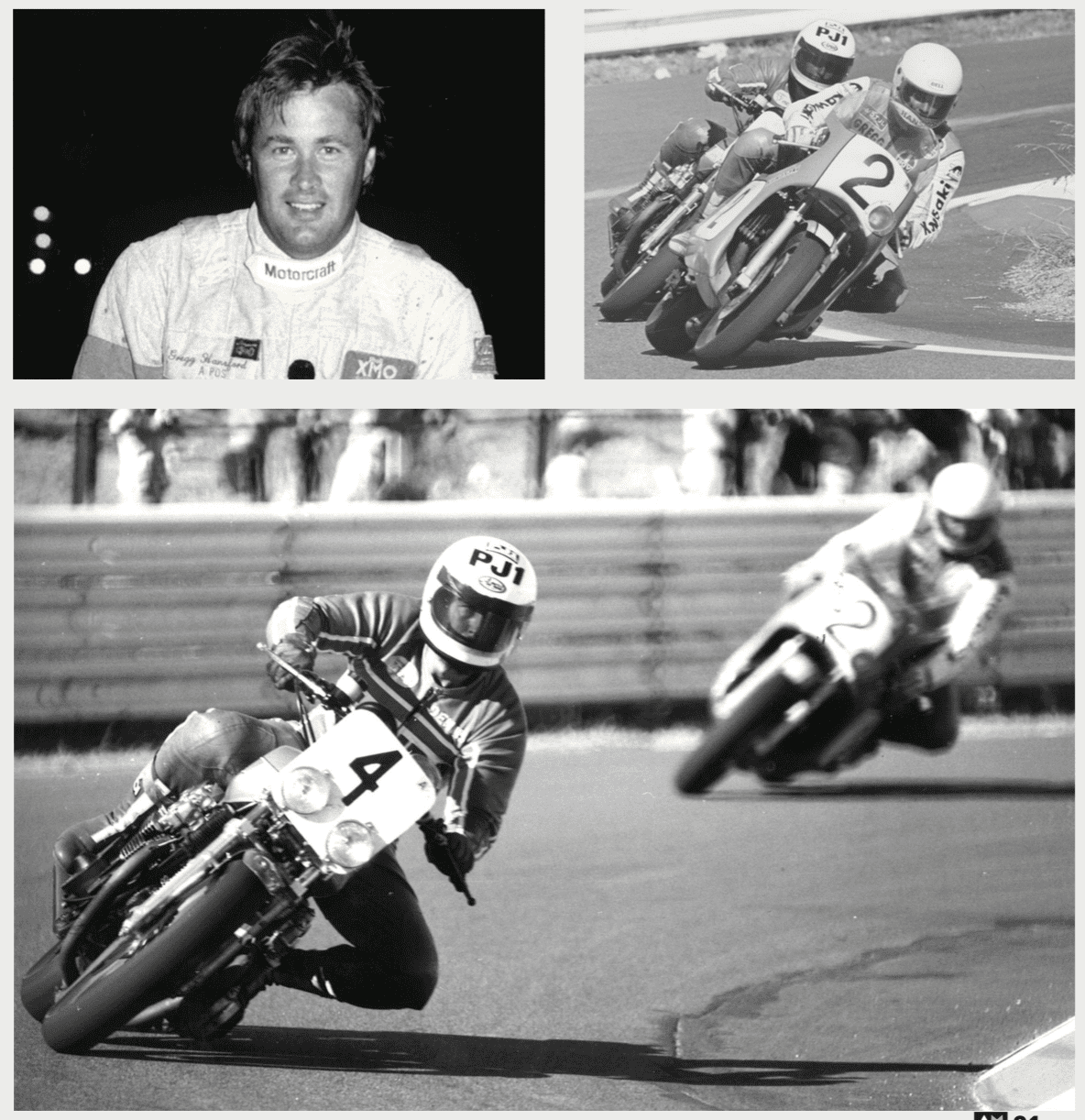

Baby boomers Kenny Roberts, Barry Sheene and Gregg ‘Harry’ Hansford were at the vanguard of the superstar revolution of the 70s, and racing has never been the same since. King Kenny is still with us, but as we all know, both Barry and Gregg have gone.

To race fans growing up in the 70s, Barry Sheene appeared indestructible. He not only survived his horrific crashes at Daytona in ’75 and Silverstone ’82 with a leer and a grin, he bounced back cheekier than ever. That he was struck down and finally defeated in March 2003 by something as insidious as cancer is a bitter irony for a man who was truly larger than life.

Gregg’s passing was shocking for being so sudden and hard to believe. How was it possible that Gregg Hansford, after racing GP bikes around Bathurst, the Nürburgring, Imatra and Spa, and then becoming a safe driving advocate, would meet his fate as an innocent victim in a Ford Mondeo at Phillip Island in March 1995 aged 42?

Although that question can never be answered, Harry and Baz will never, ever be forgotten. Here Gregg’s and Barry’s contemporaries share their memories of these two legends of the golden era of racing.

Kork Ballington

South African four-time world champion

“I first met Barry in South Africa in 1971 when he came to ride in an International event named ‘The South African TT’ at an amazing short circuit – Roy Hesketh Circuit – near Pietermaritzburg. He was an instant hit with the press and the ladies – I think these were his two areas of expertise! He could literally charm the pants off the ladies and he was a natural showman, which the press loved. He had a really good sense of humour. He was serious when he needed to be but most of the time he loved to have a laugh.

“It goes without saying that he was a great rider. His record speaks for itself. As a friend, he was always ready to help in any way he could as I experienced on a couple of occasions.

He was simply larger than life and a very rare character.

“Gregg came into my life in 1978 when Kawasaki mounted its offensive in the 250 and 350 GPs. We were ‘friendly rivals’ so to speak as he was representing Kawasaki Australia and I Kawasaki UK. When I got the contract to ride for Kawasaki in 1978 I thought, ‘Great, I have been chasing the top GP stars on my private Yamahas, now with these little green rockets I might have an easier time.’ Wrong. Along came Gregg Hansford and I had to ride my guts out harder than ever before to win a race!

“He was a great bloke. We raced on the limit, sometimes he won and sometimes I won but one thing was a given – we partied hard after the races and had a lot of laughs along the way. I will never forget at the Nürburgring in 1978. In practice I was faster than him and that evening he came over to our motorhome carrying a bottle of dark liquid. He said something like, ‘Look here Ballington, I want you to drink some of this. It will help you tomorrow’, and presented a bottle of Bundaberg OP. I did not know about Bundy OP and suggested we save it for after the race. He was joking of course and we did get into it after the race.

“His death was a great loss to us all. I have recently met his sons here in Brisbane at the Mount Cootha hillclimb. They are really nice guys, just like Gregg.”

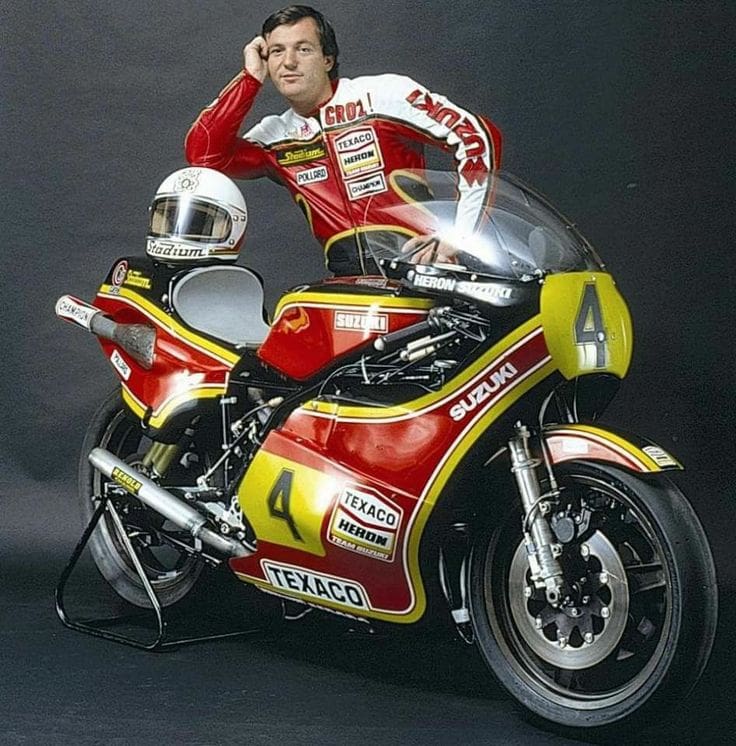

Graeme Crosby

New Zealand World Championship runner-up and IOM TT, Suzuka 8 Hours and Daytona 200 race-winner

“I arrived in Australia early in 1976 to learn that Harry [Gregg Hansford] was the ultimate demon braker, often making up lost ground on his slower Kawasaki 750. I got the chance a few times to watch and yes, he was good – very good.

“An opportunity arose one day at Oran Park – hot as hell as normal – to see just how good he was. During practice Harry and I came out of the last corner together and I thought I might test my braking skills against him at the end of the front straight.

“We were neck and neck down the straight, Harry on his KR750, me on my Z1 Superbike. The corner loomed, and I saw my mark flash by with Harry still under the screen! In a gut-wrenching split second I realised I had made the fatal mistake of even attempting to outbrake Harry. I was doomed and forced to take the escape road past the corner. I couldn’t even make a half-arse attempt as I was way past the point of no return.

“Harry suddenly sat up and braked and we both ran past the corner and up the slip road. We had both cocked up I thought – the only problem was Harry was doing a ‘plug chop’ and I wasn’t! I’d been sucked in but I did have the presence of mind to pretend to do a plug chop as well.

“Then I couldn’t start my bike, so that bloody heavy old Z1 was pushed back to the pits by an embarrassed me in 35 degrees of Oran Park heat. Flies buzzing around my face, sweat dripping off my chin, I had some explaining to do. ‘Yeah,’ I told everyone. ‘Me and Harry, we often have to do plug chops…’ ”

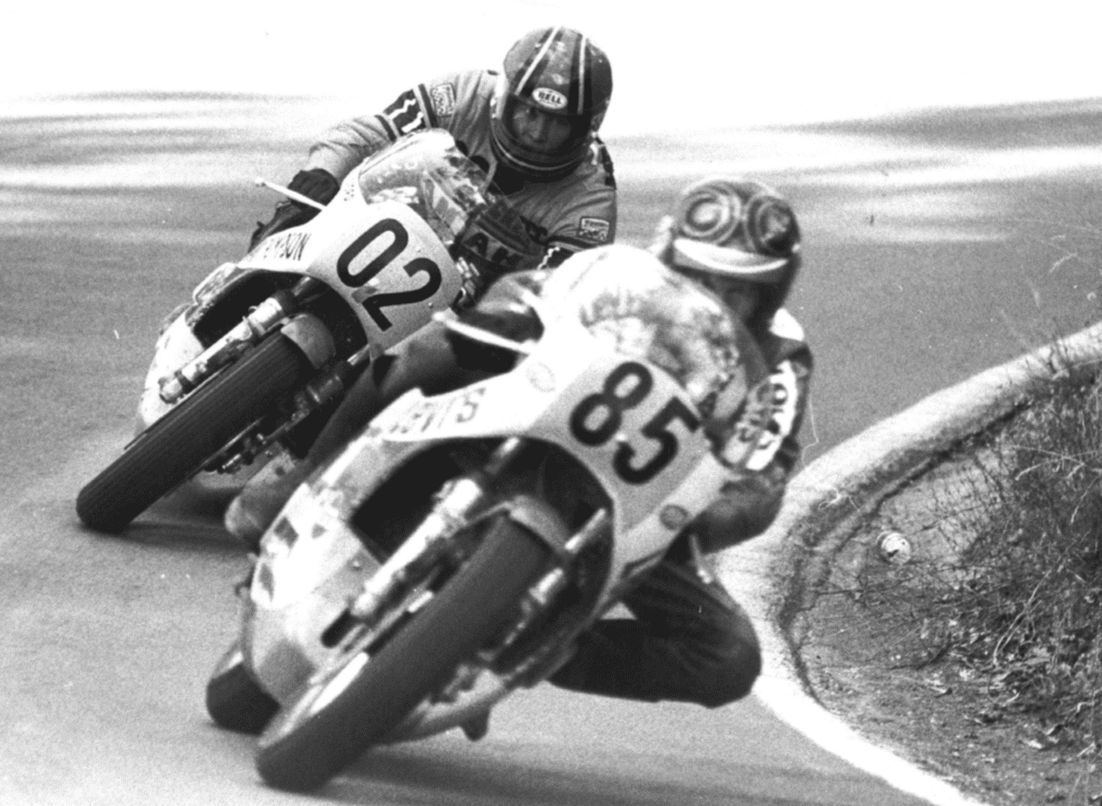

“Of all the riders in the world, I had to pick Barry Sheene to go head-to-head in the tabloids back in 1981. I crashed while leading the British Grand Prix and Barry went down too. Dusting myself off, I was met by a journalist. ‘Croz, how do you feel about ruining Barry’s Sheene’s chances of becoming Britain’s world champion this year?’ he asked. I saw red and was livid. I was dumbstruck that this low-life journo had the stupidity to even ask a question like that.

“I stopped, looked him straight in the eye and felt my top lip curl up and quiver with anger – ‘Pal, if he wants to pull the brake on and crash that’s his problem, he could have avoided it. I was the one looking back, I was the one sliding along on my arse and I saw him grab a handful of brake and down he went, don’t blame me for that.’ I turned not waiting for a response and continued walking back to the pits. ‘Bloody journalists!’

“Barry and I were always on pleasant terms but the press drove a wedge between us. I guess some people thought of me as being naive about being manipulated. Maybe, but I wouldn’t back down, so Barry and I were fair game for the press. It worked for me and it worked for Barry because we both knew the power of publicity.”

Stu Avant

New Zealand 70s and 80s GP privateer

“When I went to Europe in 1976, Barry was the bee’s knees. Phil Read befriended me as he thought I could be a foil for his arch-enemy Barry. So it took a while for us to become friends. If I was to summarise Barry in a simple phrase it is that he could ‘light up a room’. His charisma was second to none. He would be racing on a Sunday and hosting the TV show Just Amazing on Tuesday with 12 million people watching. He was extremely intelligent, almost cunning. He alone took our sport from black and white to colour.”

“The day Gregg was killed he was due to come to my 40th birthday party, and he had rung my wife to ask if he could roast me in a speech! To me, Gregg was everything that is good about Australia – blonde, cool, polite and wealthy without being ‘rich’. We were in the same circle without being at the same place at the same time. I can recall picking him up at the airport in Auckland and he walked out with a cigarette in his hand, the same as Barry. I was more of a fan of Gregg’s than a competitor as we were rarely on the same track at the same time. I just liked who he was.”

Gregg’s Bathurst return

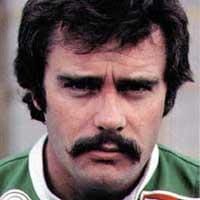

After a fierce but friendly rivalry with Warren Willing in Australia, firstly on a Yamaha TZ700 in 1974 and then on Kawasaki 750s in 1975, Gregg went on to impress at Daytona, Laguna Seca and Talladega. Next he ventured to Europe with Kawasaki team manager Neville Doyle in 1978-79 and was twice runner-up in the 250cc world championships winning 10 grands prix including his favourite, the Dutch 350cc TT in front of 150,000 fans.

He was considered one of the top three road racers in the world and Kenny Roberts rated him the most gifted rider he’d seen for just jumping on a bike and going for it. After a two-year absence, Hansford returned to Australia to compete in the 1980 Easter Bathurst races – his last ever two-wheel appearance at the circuit. He was clearly race-hardened from his week-in-week-out experience against the world’s best works stars and red-hot privateers. Even though most other GP riders would’ve boycotted a circuit like Bathurst, Gregg put the dangers to one side and dominated the 250 and 350 Australian GPs, setting lap records that would last for years.

In the Arai 500km endurance race, Hansford partnered Jim Budd on a works Kawasaki Z1000SR endurance racer. From the start Gregg faced off against Dennis Neill, who during Hansford’s time in Europe, had established himself as the absolute numero uno of Superbike racing in Australia, intimidating rivals with his take no prisoners attitude. Riding a colossally fast Honda RSC1062, Neill was afraid of nothing and no one. But on an under-prepared bike, Hansford more than answered the challenge from Australia’s fiercest firebrand. The two howled away from the field, engaging in a terrific stoush before Hansford’s clutch packed it in. It was an impressive performance from a rider who had everything to lose and nothing to gain.

Although he missed out that time, Gregg returned to the famous mountain circuit 13 years later to win the 1993 Bathurst 1000 touring car race.

When Harry Met Kevin

Claiming pole at the inaugural FIM Australian Grand Prix at Phillip Island in 1989, tall Texan Kevin Schwantz was the man to beat in the race, but highsided out of MG on lap one, his glove flying into the air. Kevin often tells the story of getting a ride back to the nearby medical centre in a car nursing an injured wrist and ego, and a total stranger beside him giving him sage advice.

“This guy was telling me, ‘you’ll come back from this, you just have to be a bit more patient’, and ‘I’ve been there before and I know how it feels’,” said Schwantz. “I was thinking, ‘who the hell is this guy?’ It was Gregg Hansford.”

WORDS DARRYL FLACK PHOTOGRAPHY AMCN ARCHIVES