Nobby Clark was a race mechanic for almost 50 years, spinning spanners for a who’s who of GP greats. He shares his tales from the circus…

Nobby Clark’s business card describes the 80-year-old as “The choice of champions”. Overleaf, a list of 15 names runs from Gary Hocking (1961 350/500cc) through to Kenny Roberts and beyond, including Jim Redman, Mike Hailwood, Barry Sheene, Jarno Saarinen, Giacomo Agostini, Bill Ivy and Marco Lucchinelli.

“I never raced myself. I don’t think I was brave enough,” says Clark, who was raised in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). “But I rode a bike, and I was interested in the mechanical side, whether it was a bicycle in the beginning or a motorcycle.

“My first bike was a 1946 James two-stroke. It did like 35mph, which my parents didn’t have any arguments about. Then I bought a Triumph Tiger 110 [a 100mph 650] and brought it home. My dad said to me: ‘Is that your bike? How fast does it go?’ And I said, ‘Maybe 50mph.’ So he said, ‘I’m taking it for a ride and if it goes more than 50 you’re not having it.’

Clark made himself popular with the Japanese at Honda by immersing himself in the country, and helping teach his colleagues English

“I had to think quickly what I was going to do. I took the advance-retard mechanism out of the magneto, so it automatically retarded. He took it out, came back, and said, ‘Yes, you can have it. It doesn’t do 40!’

Clark’s entry into the world of racing came through association.

“Gary Hocking and I served our apprenticeships together on the Rhodesian Railways. We were always talking about racing. Then he got a Triumph Thunderbird and he used to race around town with the rest of the guys. That was when [local racer] Ken Robas told him, ‘If you want to race, you should be on the circuit, not around town.’

“Gary was just unbelievable. He had talent … it was like a light switch. One minute he was on the road going as fast as he could; put him on the circuit and there was no hesitation. He was just, boom! – right there. He won his first novice race.

“Then one day he said to me, ‘You know, Paddy Driver and Jim Redman are overseas, and they’re winning races. And I can beat both of them. I’m going over.’”

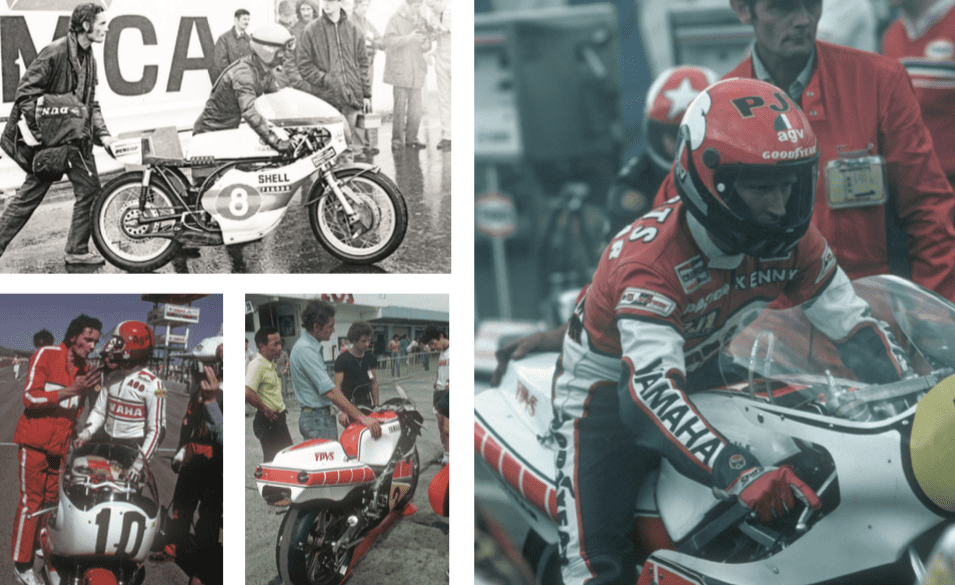

Clark worked with both Jarno Saarinen and Hideo Kanaya at Yamaha

Hocking hit the big time more or less immediately. A year later, by now a factory MV Agusta rider, he invited Clark to join him for the 1960 season.

“I was arguing with my dad right until I got on the plane: ‘What are you going to do? What are you going to eat? You can’t speak the language.’ He went on and on and on. I said, ‘Look, I’ll manage, don’t worry.’

“I worked for Gary, paying me pocket money. The MV people were very suspicious of foreigners. Arturo Magni [team chief] when I met him was sort of, ‘Well, you’re a friend of Gary’s so you can do little odd jobs here and there.’ The other mechanics didn’t want to know at all [but] later on a couple of them became really good friends.”

In 1961, Honda’s four-cylinder 250s arrived and MV Agusta ‘retired’ from racing, leaving Hocking as a privateer.

“Gary won the Spanish GP on the MV 250 twin, but he said, ‘We’re going to have a hard time with the Hondas.’ From there we went to Hockenheim and there were like eight Hondas in front of the MV. He said ‘I had to really stretch those cables’ and he blew it up. Then at the next race it blew up again and he said, ‘Right, no more.’”

Hocking won the 1961 500 crown on the MV four, and the following year was joined in the team by Mike Hailwood. The first round was the Isle of Man TT, which Hocking won… but it would be his final motorcycle race. He unexpectedly and abruptly retired directly afterwards, without taking part in the premier non-championship Post-TT race at Mallory Park. His retirement was attributed at the time to upset over the death at the TT of close friend Tom Phillis. However, Clark has a different view.

“I don’t think it’s the real story. Mike Hailwood and Socks [Hocking] each had two bikes, but one of Gary’s was very badly damaged in a crash in practice at the TT. Then Old Man MV [Count Agusta] told Arturo Magni there was no bike for Gary to go to Mallory Park.’ And Gary had a contract to go there. Gary said, ‘Hey, Mike’s going, I want my bike.’ MV said he could have his practice bike, but he wanted his racing bike. They said no.

“In the meantime, Mike’s father had been to the factory and said to Old Man MV, ‘If you give Mike works bikes and a contract, I’ll sell MVs in England. Give me 500 bikes and I’ll sell them.’ Well, Old Man MV had never had an offer like that before, so that’s why he wanted Mike to have his racebike for Mallory.

“Gary took that as an insult – he was world champion and he couldn’t even get a racebike for Mallory. Tom being killed, that was a reasonable explanation, a diplomatic way of putting it. Gary went and saw Old Man MV and said, ‘Finish, that’s that.’ And walked out.”

Clark soon joined up with fellow Rhodesian Jim Redman, who rode factory Hondas to a string of championships.

“I worked with him with the 250 fours and the 350 CR77, the twin. It was mainly international races. Now and then I’d go to a GP with him, because Honda had quite a big team at that time. Then the Japanese started to take an interest in what I wanted to do and said that for the next year we’ll meet you in Spain and go from there. I travelled with them for the rest of that year.”

Clark worked with Redman and Kunimitsu Takahashi, the first Japanese GP winner, and was clearly valued by Honda, who hired him back for 1964. At the end of the season, there was a special invitation.

“The Olympics were in Tokyo that year. Honda said to me, ‘You come to Tokyo and we can organise tickets for whatever events you want to see, and you will travel with the team, and be part of the team.’

“At the end of the Olympics and after the Japanese GP, Honda gave me two options – a round-the-world trip they would pay for, or just to go home. I said, ‘An option I would like would be to stay here and learn more about next year’s bikes.’ They said, ‘Not a problem, but where do you want to live?’ I said, ‘In a hostel’, because I knew they had a hostel nearby. They said, ‘What about food?’ I said, ‘I’ll eat Japanese food. Nobody’s dying around the place.’ And I lived a complete Japanese life for the rest of the time I was there.”

Those who know or who have worked with Clark point out not only his meticulous attention to detail, but also an amazing capacity for endurance – the ability to work non-stop for 48 hours without needing sleep. In his own more humble opinion, the honour of being taken into the heart of Honda’s factory team was for more prosaic reasons.

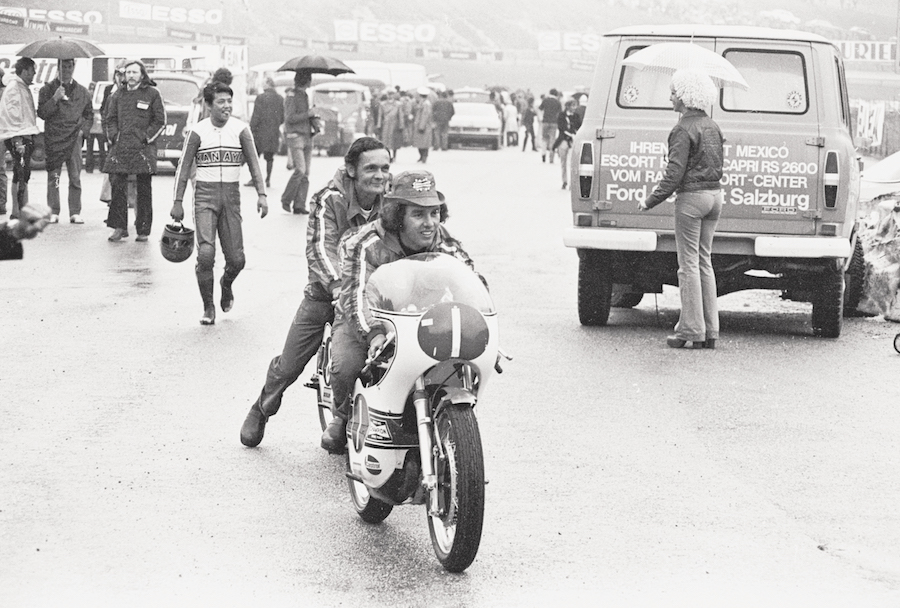

Carruthers and Clark oversee Roberts’ Yamahas during the 1981 season

“I think it was more a novelty having me there. Most of those mechanics, even Aika-san, the old chief mechanic, had never worked with a foreigner. After work in the evenings they asked me if I could help them learn English. I was learning Japanese and they were learning English…

“I worked on all the racing Hondas. My favourite was the Honda 6 from 1966 – that was a real good bike. And the 250. When they made it bigger it was good, but it wasn’t like the 250. Maybe it was because of being the first six. Being involved with that right at the beginning, that’s probably why I liked it.

“When it arrived at Monza they’d taken two exhaust pipes off and people thought it was only a four-cylinder.

“We got it into this garage, closed the doors, put the pipes on, oiled it, fuelled it, and pushed it right to the back. Then they said, ‘When we scream, you up the door and push like crazy.’ Well, you know what Monza is like…

“As it went out of the door, two or three yards, it fired up – and, man, it was like somebody dropping a bomb. They were screaming! Nobody had heard it before, and didn’t know what it was. Then everybody came and they were just crawling all over you. One Japanese guy had an oil can and he was squirting it at them, trying to keep them away. That was like a magnet, that bike.

“The first one, I think they’d rushed it too much. There were no oil coolers and it heated really quickly. It would get up to like 160º – much too hot, vaporising the fuel.

“After the first time it became easier and easier to work on, although at Honda, if you made a mistake… One of the deals was that you would assemble an engine when you were still learning it, and then straight away somebody else would take it apart and do a report on what he found. So if he found something loose, he’d make a report and the company would say, ‘You didn’t tighten this nut or screw,’ and you had to pay a fine. And they’d fine you like five dollars a week for three months. So you had to be on the ball.

“With the six, they told us that you had eight hours to do a complete overhaul – that’s taking the engine out of the frame, stripping it, washing it, grinding the valves, shaping the pistons. You had to use tweezers on a lot of parts like valve collets because the parts kept getting smaller, but your fingers stayed the same size.

“It was very reliable. The crankshafts were guaranteed for 350 miles – not a very big mileage, but 50 years ago an engine doing 18,000rpm was something out of this world. Even today… how many engines rev that high? The 50s could rev to 22,000, 50 years ago.

“I also thought the 50s were interesting because they were simple, but they produced so much power for that little engine. It was … two eggs, and 15 or 16 brake horsepower. I wondered, ‘Where is it going to end?’

“The engines were fascinating, and also the brakes on the rims instead of drums. There were some really good ideas.”

Honda quit at the end of 1967. With such bikes as the four-cylinder 500, five-cylinder 125 and six-cylinder 250/350 silenced forever, it was time to go two-stroke…

“People say there’s a lot more work in a four-stroke, but I think with two-strokes you have a lot more. You have to check so much. To have them running really good you have to open the engine up quite often. Especially on the factory bikes in those early days – checking the pistons for cracks, any score marks in the barrels, whether the rings were sticking, and for little bits of sand getting in on top of the pistons. On dirty circuits there were always problems like that.”

After Honda’s retirement, Clark went on to work with Yamaha legend Bill Ivy and then 250 champion Kel Carruthers. After that, Yamaha hired Clark directly and he went on to work with the factory-backed 1970 champion Rodney Gould on a 250. Gould was second in 1971, but to Clark his lack of commitment makes him first choice as his least favourite.

“He was probably alright as a rider, but how he won a championship I don’t know. If it rained, or if it looked like it was going to rain, his throttle hand was like that [half-closed] already. If it started raining, he would just pull in. Even if it was a grand prix: ‘I don’t ride in the rain.’ It used to annoy me when he said that. I used to say to him, ‘On a nice day, when the sun is out, I am going to get a towel and lie in the sun for the day.’”

Clark worked with Barry Sheene in the Brit’s brief sojourn with Yamaha in 1971. That ended prematurely when Sheene’s bike seized and he crashed at Imola, suffering a complicated collarbone fracture. Clark says he’d been

chasing another rider in practice, disregarding his instructions to run in a rebuilt engine. “And then of course Barry said it wasn’t his fault, it was ‘the bloody Yamaha’s’. The Japanese didn’t take well to that.”

That incident cast a long shadow when Barry sought Yamaha’s support at the other end of his career…

The next Yamaha superstar in Nobby’s CV was the legendary Jarno Saarinen, who was 250 champion in 1972 and was running away to become the first two-stroke 500 champion in 1973 when he died in a 250 crash at Monza.

“He was working for himself, wouldn’t have a mechanic, so I was working with [Hideo] Kanaya but helping Jarno at the same time. Kanaya was a factory rider, a good rider. I think a little bit under-rated.”

The Japanese rider won the 250 race on his first time at the Nürburgring in 1972, after Nobby “bought him a book of tickets to do 20 or 30 laps in the van” to learn the circuit.

Clark was with Agostini at Yamaha when the legendary Italian took the company’s first 500 title in 1974, and for his final season in 1977, but has few fond memories of that time and was happy to join Kenny Roberts at the earliest opportunity when the American decided to come to Europe in 1978.

“I’d seen Roberts at Daytona. He wanted to come to Europe and was looking for a team. I’d been in touch with Kel [Carruthers, then Kenny’s crew chief] and told him to let me know if he did come to Europe. Of the Americans, Kenny was the one – there was no dope involved with him, and he wanted to race. The other ones, it was more somewhere to play and somewhere to promote dope. There was a lot of cocaine around at the time. It wasn’t like a black market or anything … more what they were into.”

Roberts won three titles between 1978 and 1980, and retired at the end of 1983. Nobby then joined Cagiva for a fallow year with 1981 champion Marco Lucchinelli.

“Lucchinelli was the biggest disaster ever. How he managed to live with his drug problems I don’t know. Sometimes he didn’t know where he was, whether he was here on earth or on the moon. I would have fired him if he was my rider. I told Cagiva that, but they said, ‘We don’t want to fire him because he is an ex-world champion.’ So they paid him and let him stay on. There were times when he was so bad he couldn’t even stand. We’d have the bikes ready and he couldn’t even get his leg round it.”

Results were dire, but Clark says the Cagiva wasn’t such a bad bike. “It was just their system. You’d go to a race and after the last practice they would completely strip it down and check everything. I said, ‘What are you doing that for? That’s wrong, because you are disturbing everything.’ ‘No, no, we do things differently. We don’t work the Japanese way.’ I said, ‘It’s the only way you’re going to win.’”

Clark served one more year as a GP mechanic, in the offshoot Honda team for Randy Mamola on the three-cylinder Honda, “but he was another rider who just wanted to play”. Mamola was one of a number of riders who earned Nobby’s disapproval.

Another, surprisingly, was Agostini.

“One time he just pulled up. I asked him what was wrong. ‘I don’t feel like racing today.’ Yamaha’s Japanese engineer came over and when he heard that he said, ‘Next year, no contract.’

“Another time he was leading the first 750 heat at Assen by 16 seconds. There was a little bit of rain around, but not much, and he stopped. I asked what was wrong. ‘Ah, I’m not riding in the rain. Not riding.’ So I said to the other two mechanics, take the petrol out, load it up in the van.’

“An hour and a bit later he comes back and says, ‘Get the bike out of the van. I want to race.’ I said, ‘No. You’re not having the bike.’ He said, ‘But I’ve got to race.’ I said, ‘I know why you have to race – because the organisers have told you they’ll only pay you half starting money.’ He said: ‘No, no, no. I’m going to telephone Amsterdam [Yamaha headquarters].’ I said: ‘You do that. Then after that tell them to hold on and I’ll speak to them and tell them why you stopped in the first race.’ So he thought maybe he’d better not phone them…

“Hell, you drive all night, get there, things are prepared, then they come up with some stupid story like that.”

Nobby’s favourite rider was Hailwood, even over Hocking.

“For one thing, he wanted to race as much as he could, and he never made excuses. If he lost, it wasn’t my fault or the bike’s fault. He would just say to us, ‘I lost today, but I can’t win every day.’ End of story. That was fair.

“Half of them – Gould, Ago, even Kenny to a degree – would say, ‘It’s the bike, it’s your fault.’ Instead of just saying, ‘It’s history now, you can’t change it.’

Any final thoughts for would-be race mechanics?

Clark makes it sound like a matter-of-fact business: simple maintenance, albeit under the pressure of perfection. But when pressed he does go further.

“I feel it should be done with finesse. You should have feel when you work on the engine. For instance, if you are torqueing something, eventually you can actually feel one kilo of torque, so you don’t really need a gauge. But just to be sure that it is exactly one kilo, I would always put a torque wrench on. I would always be really careful.

“I worked with an Australian one year and he never used to put grease on the O-rings. I said to him, ‘You’re taking a chance. A dry O-ring, you could always nick it, and it might leak.’ He disagreed, and sure enough it started to leak.

“He asked how I did it. I said I always put a bit of grease on, and turn it in its seat. He said, ‘That takes a little bit longer.’ I said, ‘It doesn’t take as long as the rider stopping and having to change something…’”

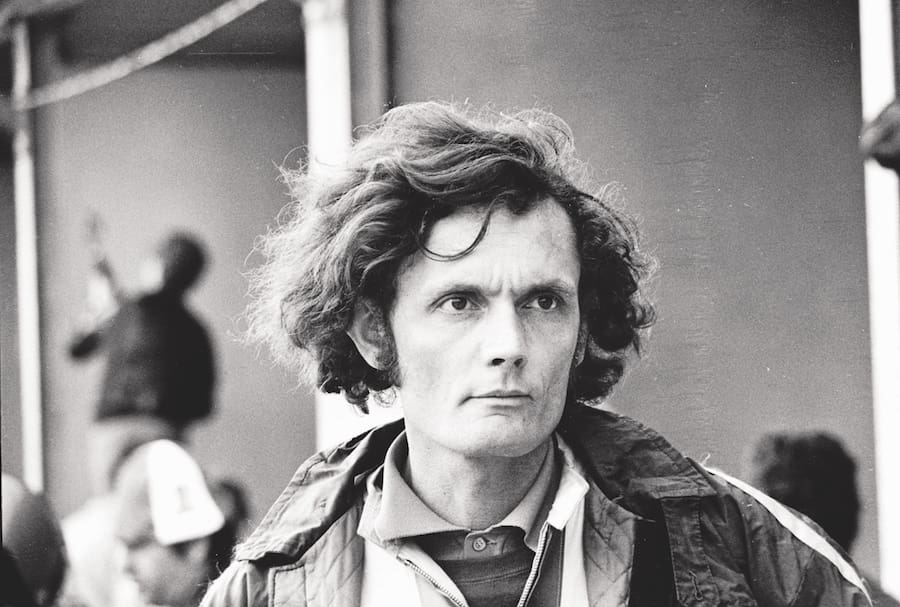

35 years later, Nobby still looks eagle-eyed

WORDS Michael Scott PHOTOGRAPHY Francois Beau