Forty years ago, global warming wasn’t a dirty phrase. Thus the sweltering summer of 1976 – which kept setting new records for warmth and days of sunshine – was something just to be enjoyed in Britain and all over Europe.

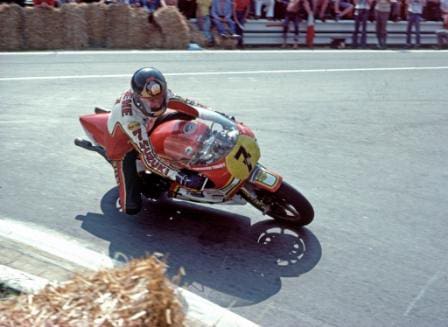

Few can have enjoyed it quite as much as Barry Sheene.

It was the year that a legend was born, as this cheeky charismatic cockney took grand prix racing by storm. He would win just one more championship, in 1977, but his era would last much longer. As Barry Coleman, biographer of Sheene’s nemesis Kenny Roberts, opined:

“Sheene was still World Champion long after he’d stopped winning.”

The year was pivotal in many ways, and Sheene was a telling influence. Thanks to his quick wit and knowing charm, his jaunty working-class manner and an unerring instinct for self-promotion, he was making bike racing sexy. At the same time, another playboy from the opposite end of the social scale was doing the same thing in Formula 1. James Hunt won the title that year, by which time the two were firm friends and instantly recognisable in all the fashionable clubs and nightspots of swinging London – shaking their locks to Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody and The Funky Gibbon.

For motorcycle grand prix racing, 1976 marked the final turning point in the battle between traditional four-strokes and the upstart two-strokes. It was the last year an MV Agusta raced, on a grid now the full-time property of Japanese two-strokes. Giacomo Agostini finished a well-beaten seventh overall. Ago did close his and the MV’s careers however with a win in the final round at the old Nürburgring – a race that Sheene did not bother to attend.

It was the year that Suzuki’s seminal square-four RG500 came of age. All six riders in front of Agostini rode RG500s. The bike would win the constructors’ title from 1976 to 1982.

And Sheene’s ascendancy marked an acceleration of a hitherto rather half-hearted move towards full commercialisation of racing. Ever the sharp operator, fully aware of the commercial value of his easy, natural popularity, Sheene ramped up his personal wealth to a hitherto unprecedented degree. Other riders, especially in years to come, would benefit from the massive hike in the scale of fees led by this one-man army.

From now on, fairings and riders’ leathers would, like Barry’s, be adorned with commercial logos. On a larger scale, in addition to the traditional technical sponsors like Texaco and Castrol, Sheene virtually single-handedly brought in money from previously undreamed of sources, as diverse as Mashe jeans and perfume giants Faberge (“Nothing,” said Barry on the TV ads, “beats the great smell of Brut.”)

I got to know Barry during these years: I was editing the monthly SuperBike magazine at the time. I found him a tricky customer. Especially after we published a satirical piece mocking the adulation heaped on his every utterance by the rest of a British media slavering at his loins. It was meant to mock the journalists and the magazines; Barry took it personally.

By MICHAEL SCOTT

Read the full story in the current issue- out now