At the onset of the Great Depression, 27-year-old Phil Irving was drafting parts for a diesel engine when he encountered the motorcycle that was to change his life – the Vincent-HRD.

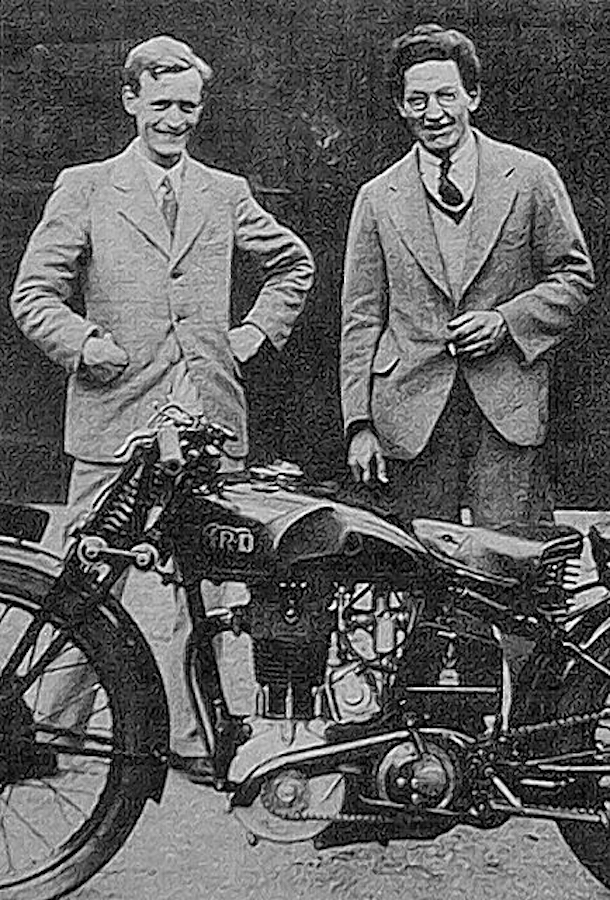

This particular machine was a well used 1928 JAP powered 600cc Model E that had just completed an epic overland journey from the United Kingdom to Melbourne. It’s owner, Jack Gill, was intent on becoming the first outfit to circle the globe. However, his travelling companion, Will Stevens, had abandoned the venture after a 12,000-mile pummeling on the pillion seat just getting to Australia.

Offered the opportunity to take over, Irving wasted no time handing in his notice and liquidating his assets – an AJS, and a HSS Velocette – as he was most impressed by the machine that would, essentially, be his home for some months to come.

The Noxall sidecar was large enough to hold a brace of petrol cans, oil, spare parts, comprehensive tool kit, selection of tinned foods and two kit-bags. On top was a complete rear wheel and tyre, plus an additional pair of tyres and tubes. All this was crowned by a Flame Thrower spotlight that could be operated from the pillion seat – and was the only thing easy about the pillion, something Phil didn’t discover until after their rough crossing from Melbourne to the tiny New Zealand port of Bluff.

The duo quickly discovered a source of supplementing their meagre savings in a way they’d not counted on – their mere presence. A radio interview paid for their hotel bill in Invercargill, and two parade laps of the local speedway paid for a sojourn in the Dunedin pub. And a local photographer did a quid pro quo, providing a stack of postcards for the rights to sell a few himself. Finances were still tight, but they were never short of friends keen to buy the thirsty Aussies a drink while listening to Jack’s outrageous tales of his journey through the Middle East.

On arrival in Vancouver, Canada, they were welcomed by the British Motor Cycle Club and a Shell representative who verified their arrangements for free fuel and oil, but there was scant information on road conditions as transcontinental travel was impossible in winter. At Irving’s insistence, they weighed the outfit ready-to-roll, which tipped the scales at 500kg – vastly overweight for an attempt at crossing the Rocky Mountains.

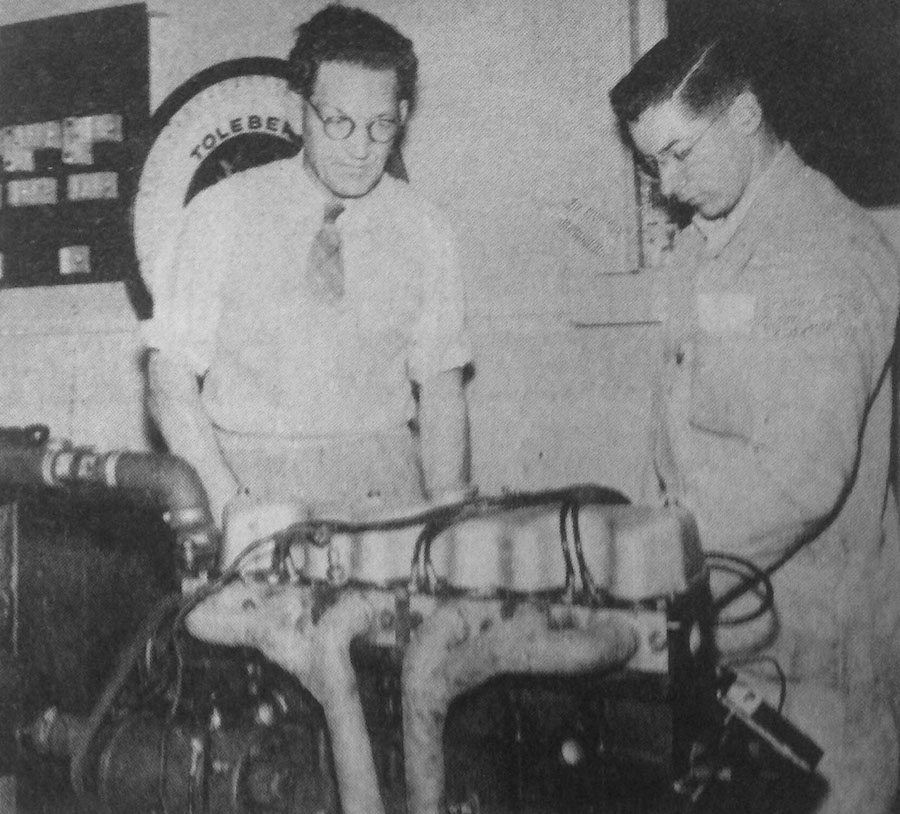

Their first overnight stop was at Chilliwack, where the cinema proprietor slung them $10 to display the outfit in front of the theatre and make a personal appearance during interval. It proved a great opportunity to flog a few postcards and was a propitious start to their North American journey. However, ten miles out of town they were in deep strife with five pieces of broken piston ring and two extremely worn spares. Surprisingly, the local garage mechanic unearthed a piston ring that was about the right diameter, though too wide and too thick. Unable to modify the ring, Phil re-engineered the piston on an old lathe and pretty soon the lads were mobile again.

What roads existed were rudimentary at best, and often somewhat notional with steep, first-gear, full-lock climbs and descents over sharp, rocky goat tracks barely wide enough for the outfit. This surface alternated with ‘gumbo’ – a description of which is remarkably similar to sticky Australia ‘black soil’ – then, inevitably, deep power-sapping sand. Mechanically they had fared well, broken sidecar springs being easy to repair, and trouble with the wheel bearings was simply fixed by fitting their replacement wheel, along with a new primary drive sprocket and chain.

However, several thousand miles over torturous tracks above the snowline took its toll and they were forced to continue with a single compression ring until a second-hand Harley piston could be found. This was ground down to fit and, after a valve grind, the motor had a new lease on life, albeit with excessive piston slap, and when Jack opened up the throttle the piston let go. According to Phil, the result “was a repulsive sight” that required a complete engine rebuild using an old well-worn single-ring piston.

After that the tracks through the forests became abominably uneven, requiring first gear and constant pushing to make progress. The constant hammering knocked the axle lug loose, breaking a sidecar spring, both of which were only made serviceable by Phil’s ever-increasing skills in bush engineering. Their problems were exacerbated when in quick succession Phil had to perform another engine rebuild and weld-up the frame, Gill was thrown into the watchhouse, the outfit was impounded, Phil was forced to spend the night in a Chinese doss house, and the final hundred miles into Ottawa took six hours.

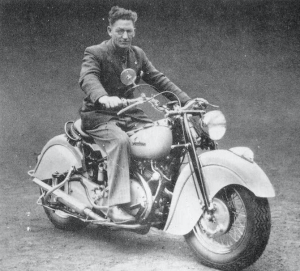

By this time the lads were skint, but Shell suggested the Cunard Line might assist and later Vincent H.R.D. agreed to pay their passage while Cunard took care of the outfit. Phil, who had intended to be away from home for “maybe a few months”, had now been on the road for almost five months. It would be almost 20 years before he returned home to Australia.

Should Phil Irving have done nothing else in his career, he would always be remembered for this epic ride across Canada, and being part of John Gill’s achievement in being the first to circumnavigate the globe on an outfit. However, over the following 50 years, Phil went on to design and build the world record breaking ‘Leaping Lena’, a Brough Superior hybrid powered by a supercharged JAP engine. Then came the famous Vincents – the A, B and C Rapides, Black Shadows and Lightnings – the model O and LE Velocettes, the AJS ‘Porcupine’ and the Repco V8 that powered Jack Brabham to victory in the 1966 Formula One World Championship. Not to mention his voluminous output of technical articles and books.

If Phil were Italian he would have been beatified and probably reached Sainthood by now, but the best our Queen could manage was an MBE. His name lives on in the CAMS ‘Phil Irving Award’, conferred on Australia’s highest-achieving motorsport engineer each year. And, of course, there’s the Phil Irving Trophy awarded at the AMCN International Island Classic.

PETER WHITAKER