There were several hungry young guns who helped detonate the 1970s MX boom. The first was the son of a fireman, Marty Smith, signed by American Honda in 1974 when he was 17. The rewards were significant. He and teammate Tommy Croft both drove Porsches in their senior high school year. While his dad around rode in Engine # 43, Smith drove a 930 Turbo and had a 911 “as a back-up”. The riches thrown at American teenage motocross champs drove an intensity to win that has yet to be repeated in any other country. It stepped up when Bob Hannah hit the pro ranks a year after Smith. As he sat beside his old nemesis in a 2007 documentary, Hannah said that he hated Smith, not personally, simply because he would be taking away the $US50,000 championship bonus if Smith had’ve won the 1977 AMA 125 title.

Hannah was born and bred in Lancaster, a town on the western edge of the Mojave Desert. His father didn’t want him to race as a kid, so Bob spent his formative years just riding around in the desert. Rather than stifle his skills, Hannah says the years negotiating the deep sand in the valleys and ravines allowed him to refine his skills to a needle point in a non-competitive environment. He washed dishes, loaded chickens and welded. His opponents had never worked a day in their lives. He rode bicycles, jogged and ran track. No-one was fitter. Like a rags to riches boxer, Hannah was bursting to breakout from his humble beginnings for a shot at the bigtime.

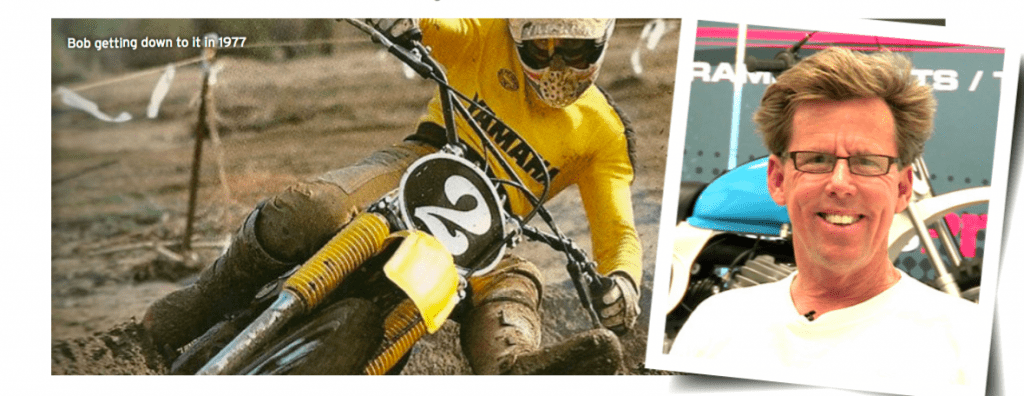

Yamaha might’ve surprised pundits when it signed 19-year-old rookie Hannah with no race credentials outside of Southern California, but nothing prepared the big names of MX when Hannah hit town. Rather than a keep a low profile, Hannah strutted around the start gate and trashed talked in his early AMA nationals like a well-worn champion bemusing the likes of Marty Smith, Tony Di Stefano and Jimmy Weinert. Looking back, Hannah says, “I was a cocky bastard.” Hannah backed up that confidence with seven AMA MX/SX championships and 70 national wins, a record only broken by Jeremy McGrath. Such was Hannah’s dominance in the late 70s and early 80s that many American observers considered him a better rider than the great Roger De Coster.

The pair faced off late in De Coster’s career, Hannah winning most of those encounters. Asked who he thinks is the better rider, Hannah doesn’t let his cockiness cloud his judgement. “If you take Roger at his best and me at my best, there’s no question Roger’s gonna win – no question. They didn’t call him ‘The Man’ for nothin’. I modelled myself on Roger, his style, his professionalism, his business mind. He had presence, and still does.”

Sensing that Yamaha had dropped the ball, Hannah switched to Honda in 1982, but he took a $US100,000 pay-cut to fit into its five-rider team. No matter, Hannah won that $100K back in the first five weeks of the season. That hunger drove him right up until his retirement. “I came from the desert, Weinert came from a junkyard in New York,” remembers Hannah. “If my dad was rich, I would’ve never made it in motocross – I would’ve been too lazy.” Although he and his young colleagues were on mega money, Hannah knew the factories were getting the better end of the stick, and he turned tables in how factories negotiated contracts with riders, forever. At one point he was receiving pay cheques from three different factories at once.

After he retired from racing in 1989, Hannah worked with Yamaha for several years before he obtained his pilot’s licence and began racing ‘warbirds’, most notably P-51 Mustangs. He once bought and re-sold a very rare Mitsubishi Zero that had been salvaged from a WWII PNG crash site. After quitting racing planes, Hannah got into back-country flying and became an aeroplane dealer working out of his Idaho property.

Around the time when Mat Mladin was racking up his seventh AMA Superbike, he bought a Scout aeroplane off Hannah. Bob could see the same cold-blooded determination that drove him in the tall Australian in equalling his seven AMA championships. Hannah got Mladin into back-country flying, sort of like extreme adventure riding in the skies, and the two catch up as often as they can. They are so close that Hannah’s wife describes Hannah and Mladin as “two brothers with different mothers.”

By DARRYL FLACK