Even sitting in pitlane at Qatar’s Losail circuit, the Kawasaki H2 looks fast. But thumb the jet fighter-style start switch and the impression deepens. As the supercharged engine roars to life you already know there’s something different going on beneath the fairings. Blip the throttle and the supercharger whirs as the induction pressure sucks the landscape towards its nose. It sounds like nothing else on the road.

With fresh Bridgestone slick tyres fitted, the sensible side of my brain told me to join the track at a steady pace and build up the speed, but deep down I knew that was never going to happen. I just couldn’t resist the urge to let the H2 off the leash. I don’t think I’ll forget the first time I wound back he throttle in anger. In second gear the instant surge of power was vicious, with the front lifting immediately as the seemingly endless torque and power fired me at the horizon.

I finished the first session tired, just a little scared, and

with arm pump from holding on too tight

The traction control was working overtime as I tapped the quickshifter, found third gear and felt no tail-off in its brutal aggression. It still surged when I threw it into fourth – and I wasn’t even using full throttle yet. My first lap was a combination of scrubbing-in the Bridgestone slicks, re-familiarising myself with the track, and trying to recalibrate my brain to calculate braking points for the H2’s brutal speed between the corners. But with the last corner approaching it was time to experience the full potential of that supercharger.

The acceleration is so strong in third, fourth and fifth gear. Think ZX-14R and some. The massive kick of torque feels like you’ve just picked up a 320km/h tailwind. By the second lap I was already seeing an indicated 290km/h at the end of the 1km main straight, before shutting off and bathing in the sound of the supercharger unloading on the overrun. It’s a unique experience.

First and second gear are almost too vicious. The first 10 percent of throttle has a real snap to it, after which there’s a seemingly relentless surge of torque and power. Some will bemoan its low-down aggression in first and second gear, but I want a bit of attitude from a supercharged superbike. I like the fact it snarls back at me and isn’t effortless to ride. The original two-stroke 750 H2 which inspired this bike was an animal in the lower gears, too.

If the original had been easy and predictable it would have been long forgotten 40 years later, rather than a much-vaunted icon of its time. The aggressive power pushes you to use a higher gear – such as taking the last corner in third instead of second and using third for the hairpin. It has so much power and torque to pull you from low down that being at the top of the rev range isn’t necessary.

Even short-shifting between corners delivers incredible drive. This $33,000 (+ORC) superbike is like nothing else you can buy, especially in third and fourth gear where you’d expect the brutality to wane a little – but it doesn’t.

At 14,000rpm the impeller shaft is spinning at almost 130,000rpm

It’ll eat every other roadbike for breakfast in these two gears. Never challenge an H2 rider to a roll-on shootout, unless you’re on an H2R. I finished the first session tired, just a little scared, and with arm pump from holding on too tight. It’s just what I wanted from a supercharged bike.

With more kays under your belt, you learn to get on the power more progressively, aware that you can’t just whack the throttle open in second gear without some form of comeback. The more you get used to the speed, the more friendly the H2 feels. You soon realise you can lean on the excellent traction control and let the clever electronics work out the available grip, and you start to dial in all that power with far more control.

You feel the chassis flex slightly, as the shock is compressed and the electronics do their thing, and it starts to become addictive. Get the bike buried into the turn, clip the apex, stand it up on the exit and hold on tight as the rear breaks traction by a few centimetres, in third, fourth and even fifth.

It’s the H2 with a ZX-6R’s power bolted on top.

You may wonder whether the H2’s 238kg weight makes it more ZX-14R than a supercharged ZX-10R? I guess a ZX-10R would lap faster than a H2, depending on the track, and the ZX-10R would stop and change direction faster thanks to being lighter. You could probably carry more corner speed, too. But the new H2 certainly isn’t a ZX-14R.

By the last session I had really clicked with the H2. I was almost used to the power and trusted the electronic rider aids – both on the power and at the end of the long straight. It was still aggressive, but it’s also predictable and consistent. The feedback gives you the confidence to keep pushing harder.

Summing up, the level of finish on the H2 is some of the highest I’ve ever seen on a production roadbike. Some won’t like the aggressive power delivery in the first few gears, but perhaps those riders shouldn’t be considering a $33K sportsbike. If you want to chase lap times get a ZX-10R, but if you want one of the most exciting roadbikes ever built, then get behind me in the queue.

Supercharger

The engine has the same bore and stroke as the H2R. Think of it as a watered-down version of the H2R – rather than the other way round. The impeller speed is 9.2 times the crank speed – which means that at 14,000rpm the impeller shaft is spinning at almost 130,000rpm. After passing through the supercharger, air pressure is 2.4 times atmospheric pressure.

Get a grip!

The traction control’s mode one is the most track-focused, while level two is for track or fast road use and level three is for the road. Or you can turn off the traction control entirely. There’s also a rain mode which limits the power to 50 percent and adds more traction control. There’s three different launch controls, a quickshifter and engine brake assist – which can be deactivated.

Frame

The trellis frame is not only a work of art, but helps with engine cooling. The extreme power creates a lot of heat and the trellis frame allows greater dissipation than a conventional beam frame. Kawasaki also wanted a little flex for high-speed stability and power transfer, which the trellis design allows. The single-sided swingarm bolts directly onto the back of the engine.

Brakes

Kawasaki has chosen huge Brembo radial mounted calipers to achieve the H2’s impressive stopping power. I was worried they may start to fade – repeatedly stopping 238kg from 305km/h – but they remained impressive. The twin 330mm front discs are 5.5mm wide and have grooves running down the centre. This helps heat dissipation.

Ergonomics

The riding position is similar to a superbike, but not as aggressive. A solo seat is the only option, so no provision at all for pillions. The seat unit effectively forms a bucket for the rider to sit in, offering greater support at high speeds and during rapid acceleration. The hip support pods that flank the rear of the seat unit can be adjusted fore and aft by 15mm to ensure a snug fit.

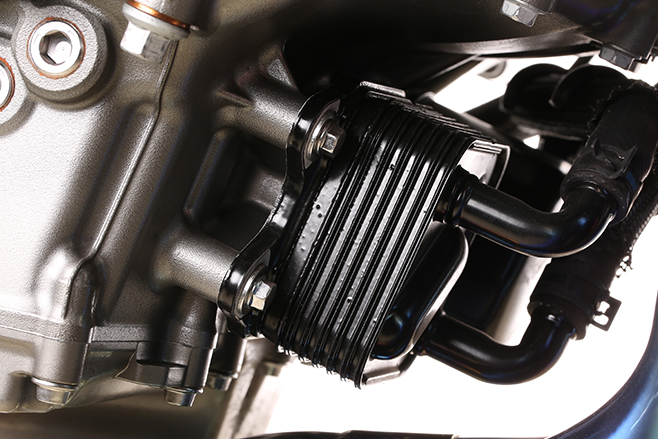

Lubrication

A single lubrication system provides cooling oil for the supercharger, transmission and engine components. Oil jets lubricate the supercharger chain connection points, cool the cylinders and transmission. As the lubrication system is servicing so many parts, the oil volume is around five litres, roughly 35 percent more than a normal 1000cc engine.

Fairings

The bodywork has three criteria: it needs to be aerodynamic, it needs to direct as much air as possible to the supercharger, and it needs to aid heat dissipation. These criteria took priority over the design aesthetics. The chin spoiler and airflow spoilers increase downforce, improving high-speed stability.

“The Kawasaki H2R is simply the fastest, maddest, most powerful production bike. Ever!”

After three hard sessions on Kawasaki’s road-going H2 my shoulders and arms feel like they’ve been filled with lead. My brain is still downloading apexes, corners and speeds, and my face has a crazed smile frozen across it. Blisters are already starting to appear on my hands from holding on in the scorching heat.

The Ninja H2 has been an unforgettable experience, but that was only the warm-up act. Now it’s time for the main event. I almost can’t believe it, but Kawasaki is about to let me loose on its 243kW (326bhp) H2R on an empty MotoGP track.

The excitement has been building for days. I couldn’t sleep on the plane, anticipation spiking my brain with adrenaline. I can’t remember the last time I rode bike that was such an unknown quantity. Yes, current superbikes are fast, but you still know what to expect. The H2R is something else, it’s packing 90kW (120bhp) more than an S1000RR. It’s the H2 with a ZX-6R’s power bolted on top.

My nerves aren’t being helped by the H2R staring at me. It’s not what you’d call a friendly looking animal, one that wants to sit at your feet in front of an open fire. No, this is a purebred pit-bull, and no-one’s even prodded it yet.

Ear muffs are being handed out to everyone in pit lane; I’m told it’s louder than a MotoGP bike. The first of the line fires up, and the Losail pit garages start to resonate, my ribcage buzzing in sympathy as a Kawasaki technician blips the throttle, warming it for battle. Then bike number two fires up, followed by a third and fourth.

It’s deafening. I throw a leg over the carbon stealth bomber and give the throttle a few blips. It already feels so much more insane than its road-going sibling. I’m given the nod and trundle down pit lane, knowing I’m about to etch new memories into my brain. I tap the quickshifter for second and the exhaust snarls a disapproving backfire. As I join the track the needle is showing only 6000rpm, but it feels so quick already, at less than 50 percent throttle.

I snick third and start to massage some heat into the new Bridgestone slicks. I’m the first person outside Kawasaki to ride the H2R, I don’t want to be the first to throw one of their $60,000 babies down the tarmac. I can already feel the differences between the H2R and the H2. The R feels like a completely different bike; it’s lighter, turns easier, holds a line better. Suspension is the same, but it’s dealing with less mass, and the settings are more suited to the track. As I reach the end of the first lap I know I can’t use the slicks as an excuse anymore – it’s time to see what it’s got.

The noise, the speed, the power. It was insane and sublime in equal measure

I hit the apex with good lean in third gear, push the bike upright and dial in the power. Oh my god its quick. The front hovers about a foot in the air and in a blink of an eye third gear is done. Keep the throttle pinned, click fourth and as I climb forward over the fuel tank to reacquaint the front wheel with the track. Fifth, still on full throttle, the gauge on the dash showing full boost. The supercharger is now spinning at something like 130,000rpm, cramming air into the aluminium airbox. I look across at the pit wall and can see blurred smudges that must be people hanging over the wall to witness me fly past. Into sixth, and it’s still pulling so hard. The Qatar straight is one kilometre long and it’s already over. I glimpse the digital speedo blitz past 310km/h, and climbing, but I need to focus on my braking point.

As I squeeze the brakes and pop out of the bubble, my brain chants ‘please work, rescue me from this madness.’ It turns out I could have braked later, as I peel into turn one trailing the brakes slightly, knee brushing the inside kerb.

I’m hollering with excitement inside my lid on the next run down the straight, pushing my braking marker a further, increasing my speed a little more. There’s loads of run-off and I’m willing to take the risk. Each time, the brakes pull me back with no fade – so impressive. On the R you can turn off the ABS, but I’ve left it on. Call me chicken, I don’t care.

The flag comes out all too early, and I trundle down pit lane feeling like I’m on the verge of bursting. I want to call everyone I know and tell them what I’ve just experienced. This will sound crazy, but in many ways the H2R is actually easier to ride than the roadbike. The chassis is more stable and it’s noticeably lighter. You can carry more corner speed and lean angle, too. By midway through the second session I’m elbow down and loving it.

Kawasaki wisely gave me time to reflect on what I’d just experienced while the sun set over the desert. Then it was time to experience the H2R at night – and that 20-minute session was as good as any ride I’ve had on any bike. I felt like a GP rider; the noise, the speed, the power. It was insane and sublime in equal measure.

My brain is still downloading apexes, corners and speeds, and my face has a crazed smile frozen across it

Some will say the power is too much, too fast, too expensive, too vicious, and yes – it’s all those things. But who cares? Thank you Kawasaki for being so brave – you promised it would be epic and you delivered. It’s the fastest, most powerful production bike ever built, and it works. Beautifully.

H2 vs H2R

Surprisingly there isn’t a huge amount of difference between the two bikes: both have the same bore and stroke, pistons and valves, even the same supercharger. The intake and exhaust systems are different, as are the ECUs, the complete wiring loom, camshafts, tyres, head gasket, clutch, aerodynamic wings and carbon-fibre bodywork. The H2R is also 22kg lighter than the H2.

Smart Thinkin’

Kawasaki chose the most efficient of all blowers: a centrifugal supercharger. Its impeller rotates at a phenomenal speed to shove air into a plenum chamber – or airbox to you and me – where all that velocity is converted into pressure. The importance of high efficiency is that power-robbing heat gain is minimal – meaning the bike can be run without the need for a bulky intercooler, saving weight and space.

Impeller

Machined from a single forged block of aluminium using five-axis CNC machining, the 69mm impeller has six blades at its tip and 12 blades at its base, all with grooves etched into the blade surfaces to help direct the airflow. The impeller’s pumping capacity at full speed is an incredible 200+ litres per second, with intake air reaching speeds of up to 100 m/s.

Airbox

The aluminium airbox has a six-litre capacity, and the pressure inside will increase to as much as 2.4 times atmospheric pressure, which is why it’s not the usual plastic construction. All that pressure has to go somewhere, which is why you can hear the H2 squeaking during gearshifts, or as the throttle is closed. This is the airbox pressure relief valve venting.

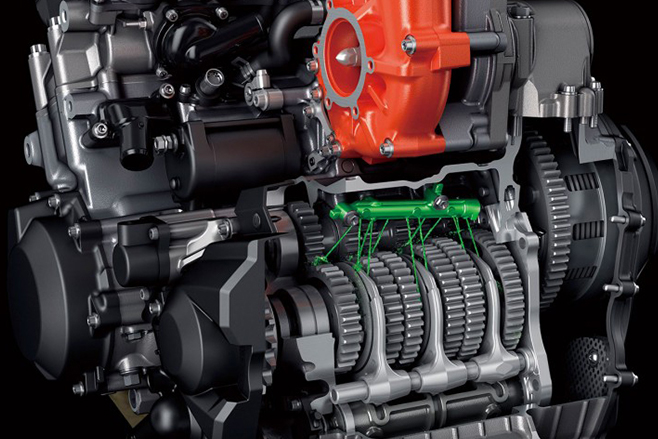

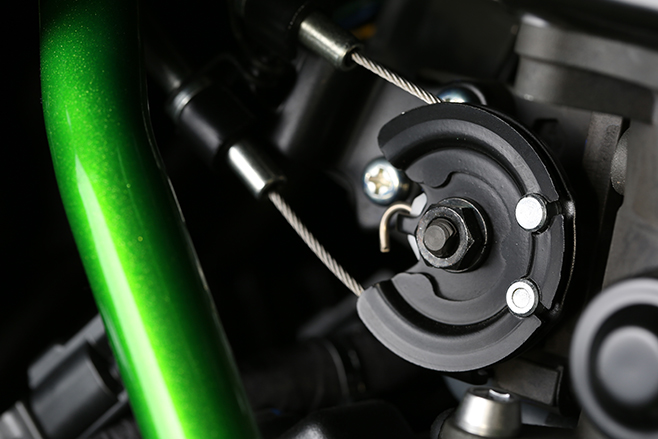

Planetary gear

The supercharger is driven by a planetary gear train, which runs off the crankshaft, resulting in a very compact unit, with minimal power loss. The gear train increases the impeller speed to 9.2 times the crank speed. The supercharger is located centrally, behind the cylinder bank, which is the best position to efficiently provide compressed air to all four cylinders evenly.

No intercooler

The naysayers, mainly other motorcycle manufacturers, claimed Kawasaki had dropped the ball by omitting an intercooler. It’ll never work they said. Well, it does. The supercharger, using technology from Kawasaki’s Aerospace Company, is heat efficient, while the water-cooled oil cooler, large coolant passageways and the lack of lower fairings means it dumps heat fast.

Transmission

To facilitate smooth, fast shifting, the H2 uses a dog-ring type transmission, developed with feedback from the Kawasaki Racing Team. Unlike a standard gearbox – in which shift forks slide the gears into position – with a dog-ring transmission the gears all stay in place, and the dog rings slide into position to engage the desired gear. So it’s a lighter, smoother, and stronger gearbox.

Injector nets

See those mesh intake covers? The top injectors spray fuel onto these stainless steel nets to create a more uniform fuel/air mixture as the fuel is sucked into the intake funnel. It also promotes fuel misting, which helps to cool the intake air and increases filling efficiency. The ECU controlled butterflies moderate the volume of fuel/air delivered into the combustion chamber.

Head work

The combustion chamber employs a flat piston crown to help prevent engine knock. The intake valves are stainless steel, but the exhaust valves needed to be able to handle the supercharged engine’s high-temperature exhaust gases: so they feature an inconel head, friction-welded to a steel stem. The pistons are cast, offering optimal heat management properties.

Gas flow

The intake ports are polished to ensure smooth flow and minimise resistance, while the exhaust ports are straight, and don’t converge in the cylinder head, promoting faster gas flow. High-lift cams allow fast gas exchange, while a wide overlap means intake air is used to help purge exhaust gases. A water jacket between the exhaust ports aids cooling.

H2 & H2R Specs

Engine

Configuration In-line four-cylinder

Cylinder head DOHC, four valves per cylinder

Capacity 998cc

Bore/stroke 76 x 55mm

Compression ratio 8.5:1

Cooling Liquid

Fueling EFI, 4 x 50mm throttle bodies

Power 147.2kW @ 11,000rpm (claimed) / H2R 228kW (claimed)

Torque 133.5Nm @ 10,500rpm (claimed) / H2R 165 Nm (claimed)

Transmission

Type Six-speed

Clutch Wet

Final drive Chain

Chassis

Frame material High-tensile steel

Frame layout Trellis

Rake 24.5˚ / H2R 25.1˚

Trail 103mm / H2R 108mm

Suspension

KYB

Front: 43mm USD, adjustable rebound, compression and preload, 120mm travel

Rear: Monoshock, adjustable

compression, rebound and preload, 135mm travel

Wheels/Tyres

Wheels Five-spoke, cast aluminium

Front: 17 x 3.5 Rear: 17 x 6.0

Tyres Bridgestone Battlax Racing Street

Front: 120/70ZR17 (58W) / H2R 120/600R17 (soft)

Rear: 200/55ZR17 (78W) / H2R 190/650R17 (med)

Brakes

Brembo

Front: Twin 330mm discs, four-piston radial calipers

Rear: Single 250mm disc, two-piston caliper

Dimensions

Weight 238kg (wet, claimed) / H2R 216kg (wet, claimed)

Seat height 825mm / H2R 830mm

Max width 770mm

Max height 1125mm /H2R 1160mm

Wheelbase 1455mm /H2R 1450mm

Fuel capacity 17L

Performance

Fuel consumption Not given

Top speed Over 320km/h / H2R 360km/h

Contact & sale info

Testbike Kawasaki

Contact www.kawasaki.com.au

(02) 9684 2585

Colour options Mirror coated black

Warranty 24 months, unlimited km

Price

H2 $33,000 (+ORC)

H2R $60K (+ Pre-delivery Inspection costs)

Aus availability Now

This article appears in AMCN Vol 64 No 19