Highly modified 1000cc four-stroke engines in production bikes had by 1980 brought vast quantities of power. But even heavily altered roadbike frames couldn’t cope with the increased stresses, which left the big-bore racebike market open for skilled frame builders to fill the void.

During the ensuing decade, racebikes framed by Steve Roberts and Ken McIntosh won six consecutive New Zealand Formula 1 titles, not to mention numerous major New Zealand and Australian international races and series.

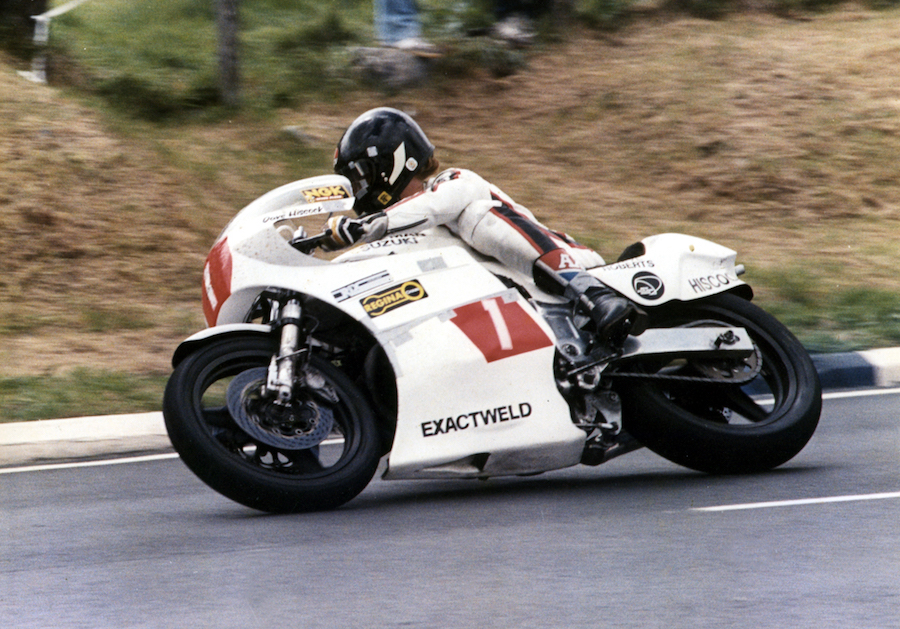

Among Roberts’ greatest highlights were the results that Dave Hiscock gained on the Aluminium Monocoque in 1982 – a Swann Series crown, third in the world TT F1, third in Britain, and third in the hardest race on the planet, the Isle of Man TT. Achieved against the odds, against numerous factory bikes with well-paid and highly experienced riders. Hiscock, on the other hand, did it living in a tent, and often with just a handful of laps of practice.

Born in Hertfordshire, England, Roberts began working with aluminium while serving an apprenticeship with the de Havilland Aircraft Company. He then rebuilt smashed cars for a London Jaguar agent before joining Aston Martin to hand-build DB4s and Lagondas.

After a year with Aston Martin, Roberts and wife Pam emigrated to New Zealand in 1962, arriving with seven shillings and sixpence to their names. He became a panel-beating tutor at the Wellington Polytechnic before leaving in 1977 to begin a career working from an old shed on his six-hectare property near Wanganui. Here, he eked out a living restoring historic cars and making motorcycles.

He’s still there, and so is the historic shed.

Roberts’ first monocoque chassis came quite a bit earlier, in 1967. Destined for a motocrosser, it was manufactured from fibreglass.

“I built the tank, seat, rear guard and the airbox all in one piece,” Roberts explains, now realising that, had he put on a headstock and if the fibreglass was not so brittle, it could have been a winner.

Roberts knew what was needed, having ridden scramble bikes for seven years. He also owned Suzuki 250 and 400 off-road bikes, while his roadbikes included a Douglas G35, a 1939 plunger-frame Manx Norton, a Norton Dominator and a 1937 Triumph T70.

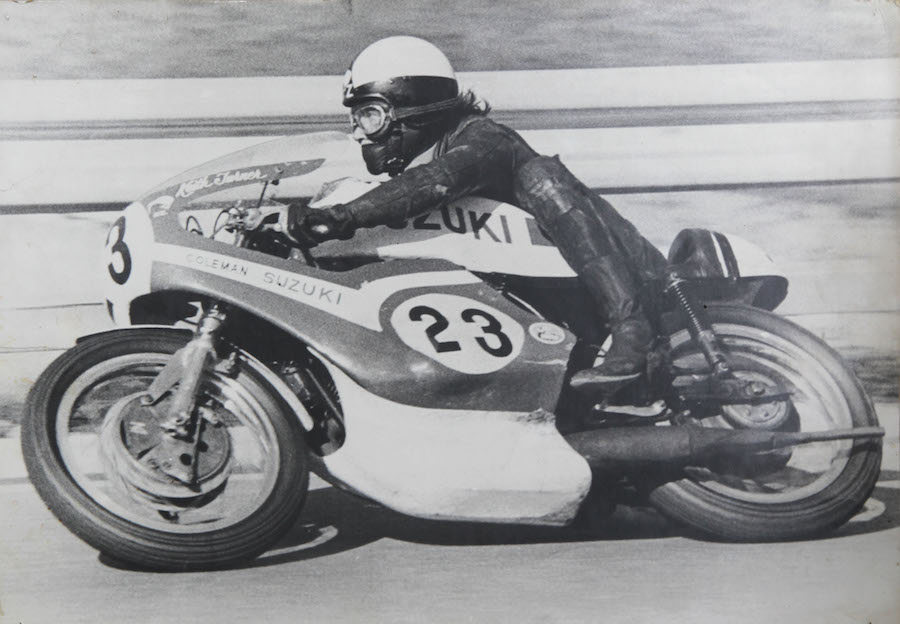

Roberts found himself making replica Suzuki TR500 factory racers between 1969 and 1974, based on a factory TR500 he measured up in Wanganui. “The first one was a copy, and I modified them from there on. We originally started with a TR500, but in the end the factory was buying our bikes! Pat Hennen (1975 Marlboro Series winner) rode one. We even supplied two to Suzuki UK.”

Prominent riders to race Roberts-built TR replicas to success were Warren Willing (TR350 & TR500), Dale Wylie (1974 Marlboro Series winner), Geoff Perry, Ginger Molloy, John Boote, Ron Grant and Mike Sinclair (TR250).

“I’m a bit of a fan for monocoque bikes,” Roberts says. “We did an aluminium monocoque for Keith Turner in 1972 with a TR500 motor. He was second in the 1971 world 500cc championship on one of our replica Suzukis the year before.”

Not bad for a bike turned out of an old farm shed in New Zealand!

At the end of 1981, and after two successful seasons racing the first McIntosh bikes, Kiwi international Dave Hiscock was looking to build a bike to compete in the 1982 TT F1 World Championship. Heading back to Europe for his second northern-hemisphere season, his bike needed to be something special if he was to get noticed and gain a factory ride.

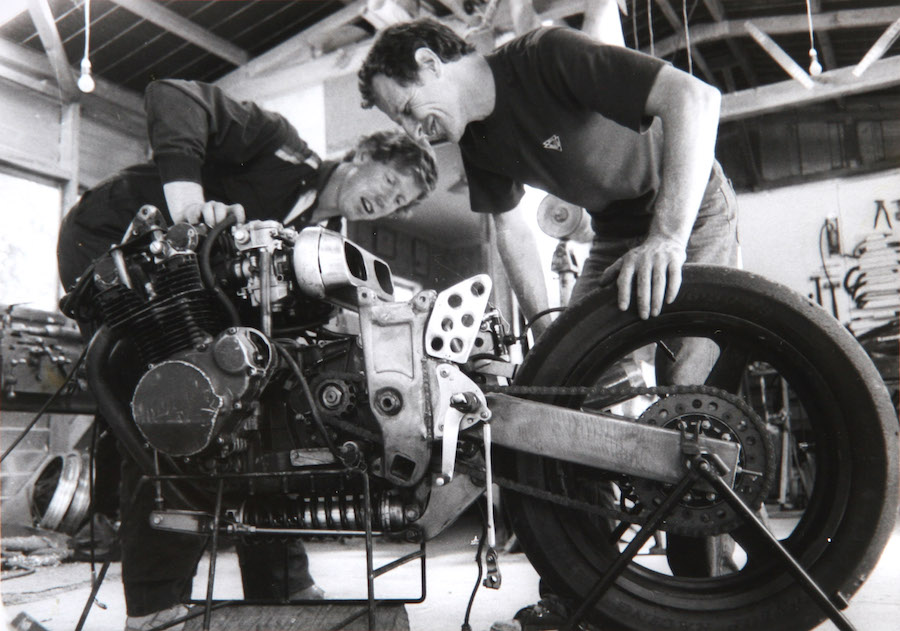

So, after measuring Graeme Crosby’s world title-winning factory Suzuki XR69 F1 bike, Roberts began construction of the Coleman Suzuki GS1000 Aluminium Monocoque bike in January 1982.

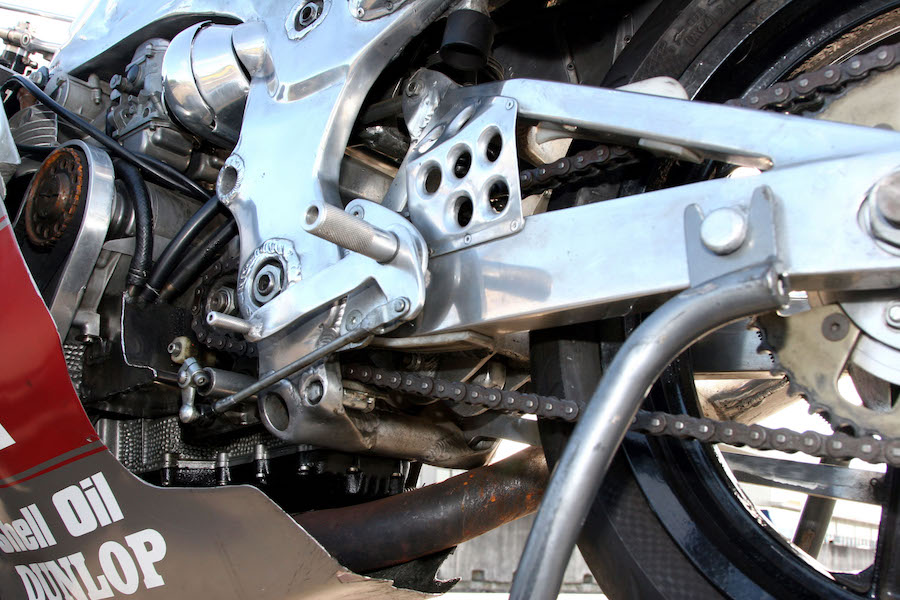

The single-section monocoque incorporated the steering head, fuel tank and the vertical structure for the swingarm and rear engine mounting bolts, all of which made short work of replacing an engine on race day. Both engine-mounting bosses and the swingarm pivots were fitted with steel inserts.

The alloy monocoque frame was entirely oxy acetylene gas-welded by Roberts with distinct, flowing Katana-like lines seen from almost any angle. Initially the front fork assembly was from a Katana 1100.

“But when I started to do well, Suzuki UK loaned me a works front-end (Kayaba forks, magnesium triple clamps, works discs, calipers and fluid reservoir) which I used for the second half of the season and for the Swann Series,” Hiscock recalls.

Roberts also redesigned a rising-rate rear linkage system similar to but better than the XR69, and so close was Roberts’ final design that someone attached Suzuki Full Floater stickers to the swingarm while in Europe!

Sponsor Rod Coleman, the 1954 Junior TT winner, organised a twin-spark Yoshimura GS1000 engine handbuilt by Pops Yoshimura, with the hope the new bike would be as fast as the factory machines.

The aluminium monocoque chassis travelled to Britain in Hiscock’s suitcase, while the motor arrived direct from Japan.

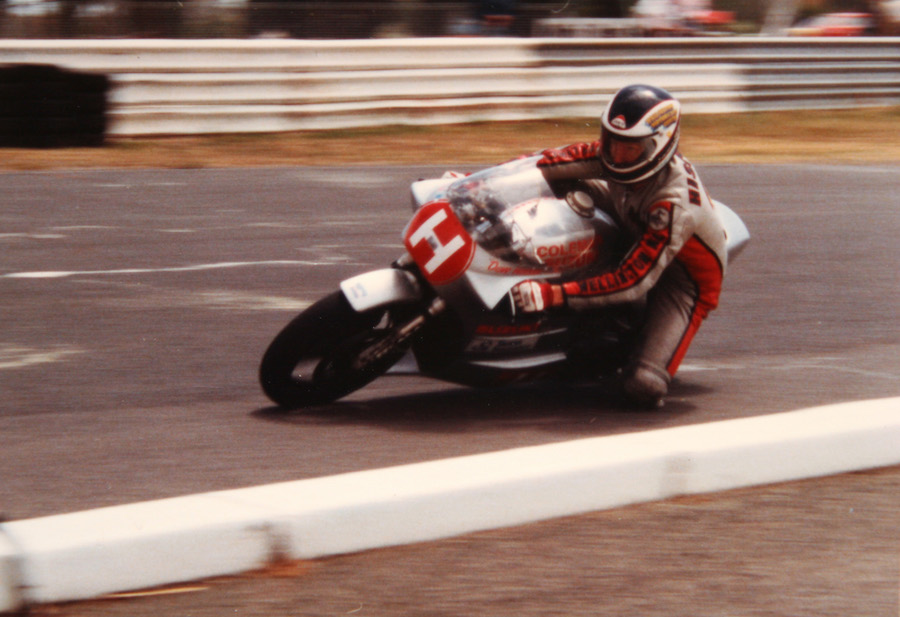

Vindicating the Roberts design and hard work on his very first race on the Coleman Suzuki, Hiscock finished second in the opening round of the British TT F1 Championship at Cadwell Park on 4 April 1982. Factory Suzuki rider Roger Marshall won the race, but behind Hiscock and his home-made machine were high-class riders such as Joey Dunlop, John Newbold and Mick Grant!

The Isle of Man is the toughest of proving grounds, as it’s hard and unforgiving on machinery. Despite the odds, Hiscock rode to third in the TT F1 class, and ninth in the Classic TT.

Racing against the world’s best four-stroke riders – the likes of Ron Haslam, Dunlop and Wayne Gardner on works Hondas – Hiscock finished third in both the three-round World TT F1 and six-round British TT F1 championships. He was leading the British series by two points and very nearly won the title but for an electrical problem while leading the final round at Brands Hatch. He finished the race in fifth, handing Marshall the championship.

After the British season, Hiscock raced the Aluminium Monocoque in the 1982 Australian Swann Series. He didn’t finish the first leg at Sandown Park, yet still won the series after recording several race wins and high placings, as well as a lap record.

On arrival back in NZ, Hiscock debuted the Aluminium Monocoque at Pukekohe, where he smashed Gregg Hansford’s long-standing lap record.

A few days later the Coleman Suzuki arrived home at Wanganui for the 1982 Cemetery Circuit races, with a fine collection of international wins and high placings already under its seat. So it was no surprise when he won the second race ahead of riders of the calibre of Rodger Freeth (McIntosh GSX1100, for which Roberts made all the fuel tanks), Bob Toomey (McIntosh GS1000) and Australian Paul Feeney (Kawasaki Z1000).

After a few more victories, Hiscock’s final ride on the revolutionary racer ended in fine style at New Zealand’s Bay Park Raceway, where he fittingly recorded a pair of wins against tough opposition.

Current owner Kevin Maxwell bought the bike in 1984 and raced it for two years, including in the 1985 Australian Swann Series, before retiring one of New Zealand’s most successful racebikes.

The Coleman Suzuki was a race winner and a mobile work of art. For its time, it was highly innovative and crafted to perfection, but by the end of 1982 Roberts had another monocoque project brewing…

Hiscock had been hugely successful on the Aluminium Monocoque GS1000, but it wasn’t quick enough to head off the new factory Honda V4 RS850R for 1983. He had been in line to receive a factory Suzuki, but Barry Sheene returning to the Suzuki fold firmly soaked up the budget.

After a typical pub meeting, the world’s first carbon-kevlar monocoque was designed and crafted by Roberts with the sole purpose of getting Hiscock noticed – and a factory ride for 1984.

A prototype was completed and test-ridden in early February 1983 using the Aluminium Monocoque’s fairing and GS1000 engine, with the factory Suzuki front-end. The swingarm, rear suspension, brake rod, footpegs and lower engine were all attached to a small aluminium subframe.

The unique underslung rear suspension unit was Hiscock’s idea, as the aluminium bike’s shock overheated behind the engine. The linkaged unit became known as ‘Tension Suspension’, where the shock worked in reverse to a normal unit. It provided increased rear wheel travel as well as a more gradual linkage system.

It took a little less than six weeks to build the second ‘plastic’ bike, dubbed the Coleman Suzuki Plastic Fantastic.

“We had two months to get it to the Isle of Man and racing,” Roberts recalled. “It was a real struggle.”

When Hiscock arrived in England he fitted a four-valve Yoshimura GSX1000 engine – straight from Pops. The bike had not been raced or ridden anywhere else before then, yet Hiscock placed eighth in the TT-F1 race and held fourth in the Classic TT until a piston broke.

A lot of important people were taking notice of the bike by now, not least Honda!

Dogged with bad luck, things didn’t go Hiscock’s way that season.

He next rode the Plastic Fantastic at a Donington Park international meeting and recorded the fastest lap, but in the race he was running second and in striking distance of a win when an ignition timing bolt broke.

Worse was to come at the Dutch round of the World TT-F1 championship the following week. He suffered a high-speed crash that smashed his knees and severely damaged the bike. The carbon-kevlar monocoque remained intact.

Recording only one finish, Hiscock placed equal 12th in the 1983 world championship, and he never returned to Europe.

The Plastic Fantastic’s first Kiwi race was at Wanganui on Boxing Day in 1983, where Hiscock won two legs of the prestigious Bryan Scobie Memorial Trophy – regarded as the first win in the world for a kevlar-carbon framed motorcycle.

Hiscock scored three wins at Gracefield a few days later to wrap up 1983 Pan Am Countrywide International Series.

With Hiscock off to race in South Africa, Robert Holden raced the Plastic Fantastic in the NZ championship using a standard GSX1150 engine, which earned him the 1983/84 NZ F1 title ahead of Freeth on his McIntosh GSX1100.

The following season Holden purchased the bike and went on to win the 1984 Brut 33 Countrywide Series, winning almost every race. But, although Holden took occasional wins during the following national championship races, the ‘Plastic’ developed increasing engine problems.

Next stop was Bathurst 1985, where it didn’t get any better – the motor blew in practice before the Arai 500 race. The Roberts monocoque marvel was retired shortly thereafter and is currently owned by Wellington enthusiast Graeme ‘Spyda’ Staples.

In the meantime, Roberts had built a Plastic Fantastic Mk2 in 1984 for Norris Farrow that, including the prototype, was ‘Plastic’ number three. The second generation incorporated a few modifications; a 16-inch front wheel, altered steering angle, longer-travel Tension Suspension linkage system, and reverse air ducts that came out the sides of the tailpiece.

While the rake angle of the fork remained the same as the earlier bikes, the triple clamps were altered to give quicker steering response. Further refinements included remoulding the carbon-kevlar monocoque chassis, with some areas receiving additional material to provide added strength.

Although Farrow won the 1985 Penang Grand Prix and placed third in the 15-lap Bathurst Centenary race that year (timed at 290km/h on Conrod Straight), the Mk2’s GSX1150 engine kept breaking down at key moments.

After a tough season, Farrow sold the Mk2 to Blair Briggs, who raced it for two seasons in NZ before taking it with him to Australia in 1986, where it still takes pride of place and gets rolled out occasionally for demonstrations.

Did you know?

During the mid-1980s in the USA, Erik Buell spent almost an entire day taking photos of the Plastic Fantastic’s underslung rear suspension design – which later found its way onto his Buell roadbikes! Ever humble, the innovative suspension’s designer and constructor, Steve Roberts, simply took it as a compliment.

By Terry Stevenson

PHOTOGRAPHY Steve Green, Dave Anson, Don Tustin, Steve Roberts, Phil Aynsley & TS