Is it really 40 years since the 1977 Castrol Six Hour Race? No wonder I feel 68. It’s a good thing I keep diaries or plumbing the grey matter for anecdotal evidence of that weekend, plus a few others, would be a tough job.

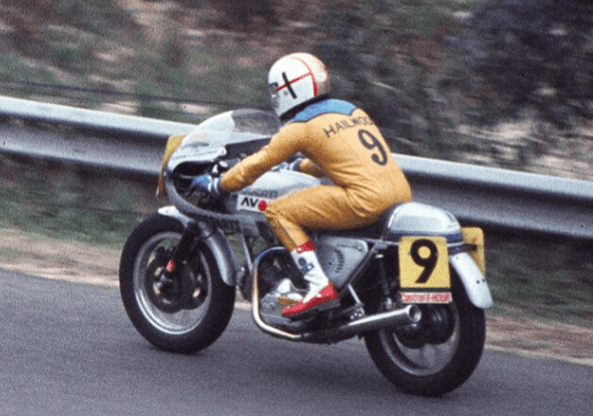

Of course, the ’77 Six Hour was the race where Mike Hailwood, nine-time world champion and winner of 76 grands prix and 12 Isle of Man TTs, pulled on leathers again for something approaching a serious race, as opposed to a bit of fun on historic bikes. His one stipulation in agreeing to the race was that it also had to be first and foremost, fun. And considering the level of competition he’d faced over the previous 20 years, it isn’t that difficult to place the Six Hour in the semi-fun category at least.

Yet for the vast majority of the field, it was anything but. This was the big race of the year and there was serious money invested in getting results. At this stage, local production racing was still on the cusp of the all-out tyre war and the subsequent rule bending that ultimately consumed the category. In 1977, at least in the Unlimited class, it was a choice of Dunlop TT100, Avon Roadrunner, or Metzeler, all of which were standard road or touring tyres.

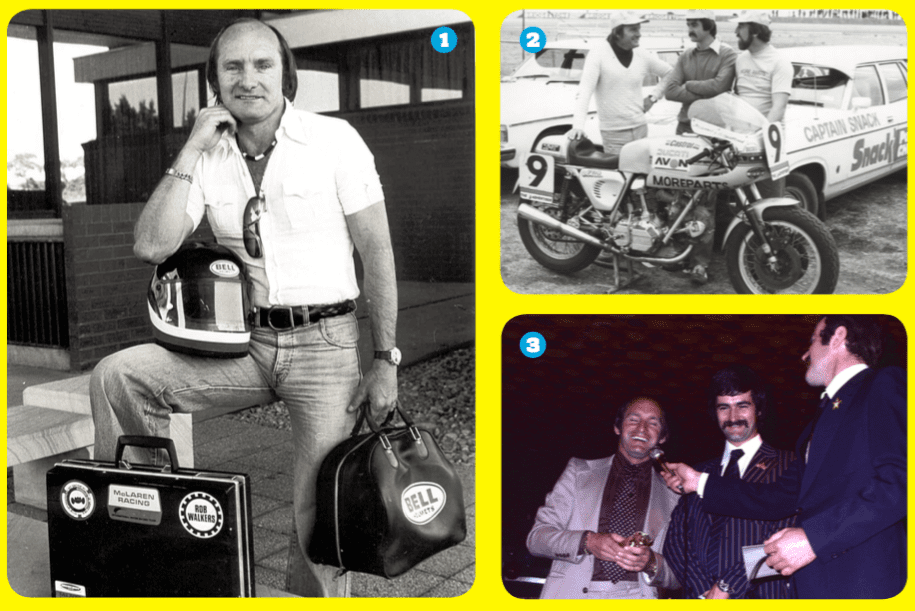

After an accident in the 1974 German Formula 1 GP that left him with a severely shattered right ankle, Mike had struggled to come to terms with a life that no longer involved racing in a different country virtually every weekend, and the prospect of holding down a real job sat uneasily with him. Even marriage, a union that he had previously scoffed at, was now a reality following his tying the knot with Pauline in 1975. And home was now Auckland, about as far from his previous jet-setting playboy existence as you could get. Given the advancing level of ennui that his job as a partner in McLaren Marine in Auckland brought on, it came as little surprise to his close friends that Mike began to embrace a proposal to saddle up for the 1977 Castrol Six Hour.

That proposal blossomed from an on-air conversation between Mike and radio personality Owen Delaney, who was doing a short stint at the time in Auckland. Owen was a real petrol head, with a collection of racing bikes and cars back in Australia. At first, Owen had cheekily suggested that he and Mike team up on a Yamaha RD350, but he quickly realised the folly of that idea. I had known Owen for a while, mainly because he was engaged as the series commentator in the Mr Motocross Series which was promoted by close mate Vincent Tesoriero, but it still came as a shock when the phone rang.

“How would you like to team up with Mike Hailwood for the Castrol Six Hour Race in October”, was the opening gambit. Owen had a reputation as a bit of a joker so my immediate reaction was to tell him to piss off. I replied with something like, “I’m busy, stop pulling my leg.” But it wasn’t a joke, and with typical gusto, Owen set about making it happen.

He had a friend, Malcolm Bailey, a former car racer who owned a motorcycle dismantling business called Moreparts in Newcastle, and somehow Owen convinced him to buy a new 750SS Ducati and assemble a team to run it.

There were a few other minor issues to deal with. In a letter agreeing to do the race, Mike had said with typical off-handedness: “Of course I should expect my expenses to be paid”. Yes, I should think so too. There was no mention of any kind of fee, and from a nine-time world champion who had been a professional racer from the age of 18, this was quite remarkable.

We soon worked out that despite having the basic hardware and the best intentions, some sort of cash budget was going to be necessary – in other words, a sponsor. It wasn’t really my responsibility to come up with the budget, but I sensed that the euphoria of the occasion (i.e. having Mike actually keen to come on board) had rather swept away the harsh realities.

Fortunately I had lots of mates and contacts within the advertising industry, and in fairly short order a deal was struck with the giant company Amatil, which handled, among other things, Coca Cola and various cigarette brands, to come to the party with a new brand of potato chip called Snack. And so the Moreparts entry became the Snack Racing Team. Avon importer Lindsay Walker provided the tyres, but there wasn’t much more in the way of assistance. The pit crew consisted of Malcolm, his wife June, Alan Kay and some mates from Newcastle, with the chief mechanic from the Moreparts motorcycle wrecking business, Neil Cummins, in charge of the spanners.

Most of the top teams were at Amaroo Park weeks ahead of the event, but Mike didn’t even arrive until the middle of the week before the race. Although we had kept everything low key, as instructed, a phalanx of television journalists was at the airport. Jack Brabham miraculously appeared, as did a Ducati on which both the champions were photographed. Then it was off to the track, where everyone was thrashing around, testing tyres and practising pit stops. Mindful of our comparatively meagre resources we did few practice laps, and nobody considered that a fuel consumption test was necessary, so we didn’t do

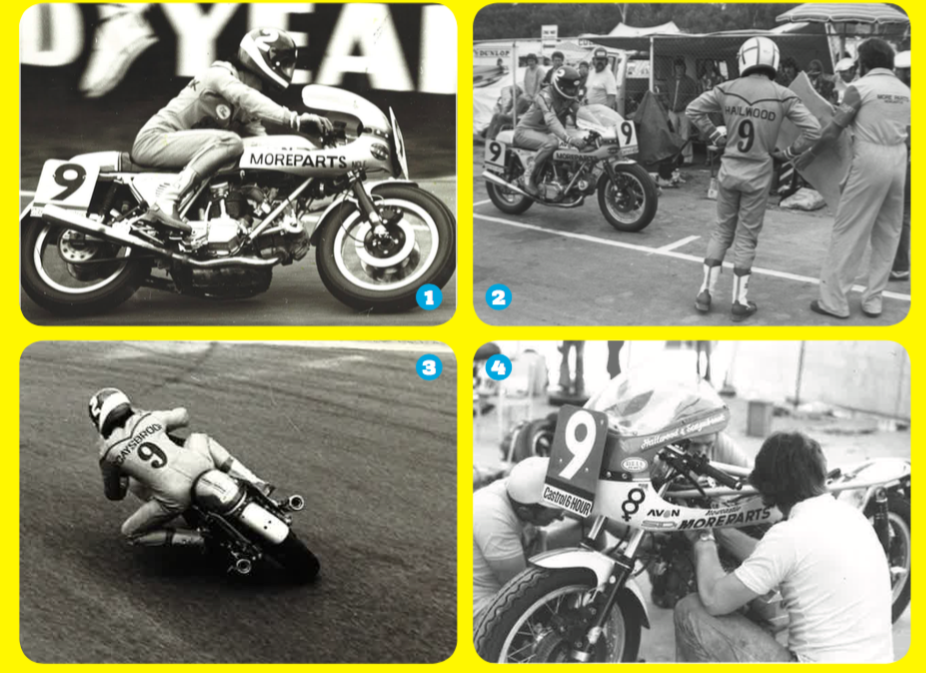

that either. Mike seemed to take to the Ducati easily (funny about that) and we got through the official practice sessions without any dramas. In qualifying I was slightly quicker with a lap of 60.2sec and we lined up 13th on the grid, third among the 750s, although 1.1sec slower than Alan Hales on the remarkably quick Z650 Kawasaki.

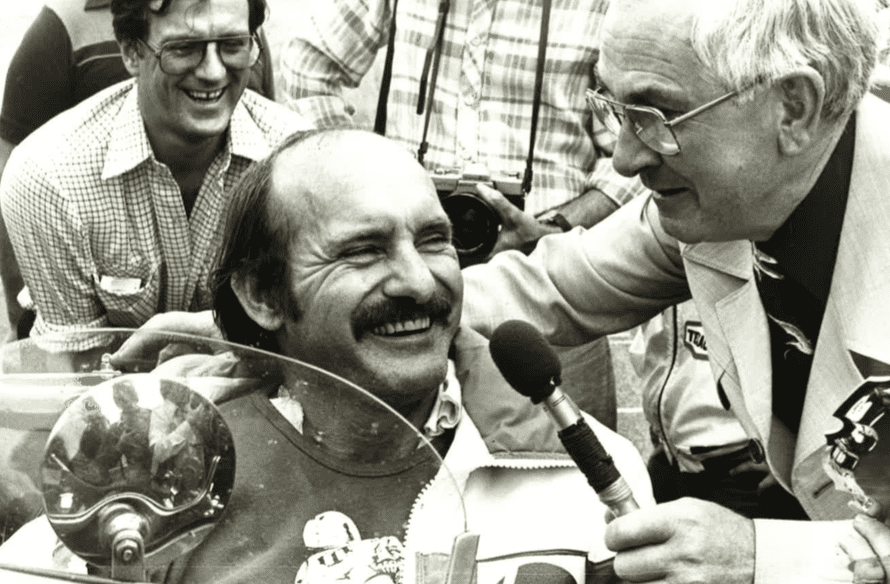

The Six Hour was a big event in its own right, but I have a feeling Mike’s appearance had something to do with the size of the crowd that was queued up for several kilometres along Annangrove Road when the gates opened. Because of Mike’s gammy leg it was decided that I would take the Le Mans start, which involved kick-starting the Ducati while most other riders simply pushed a button.

I was extremely nervous about this, because the opening laps were hectic affairs invariably punctuated by pile-ups, and if I chucked the bike away before Mike took his stint I reckon I would have been lynched. Things turned out for the best, however, and although there were a few prangs I avoided them and even put in some sub-60 second laps before handing over to Mike when the race was 72 minutes old.

It was here we realised I should have stayed out until the 90-minute mark, thereby reducing our pit stops from four to three, because there was plenty of fuel left in the tank. It also meant that I would have to do three sessions to Mike’s two. All that may be true, but I was never so glad to get off a bike as I handed over and Mike motored out of pitlane and into the race, to a thunderous roar from the spectators packed on the hill.

At the end of the six hours, we had racked up 350 laps to claim sixth outright, the second 750 home. We practised, qualified and raced on the one set of Avon tyres, and the bike had run like clockwork, except, as noted in the AMCN report, when I missed third gear once coming onto the straight.

After the chequered flag fell, I did one more lap before being ushered into parc ferme which was a roped-off area on the inside of the circuit, and I clearly remember feeling that I was able to faint when Neil switched the engine off. But there was no time to get involved in mental exhaustion – there was too much back slapping and popping of corks. In fact so many corks were popped that none of us was in a fit state to drive home. Just who did get us back to our house in Cammeray I have no recollection, but the next morning I awoke to find Mike sound asleep on the chesterfield lounge in our living room, still fully clothed. We had rather exceeded our expectations, and we certainly fulfilled Mike’s directive that it had to be fun.

That should have been the end of the story as far as long-distance production racing was concerned. But the Amatil people had been well pleased with the publicity generated for their Snack brand, and a plan was hatched to reform the team to compete in the Adelaide Three Hour Race in April 1978.

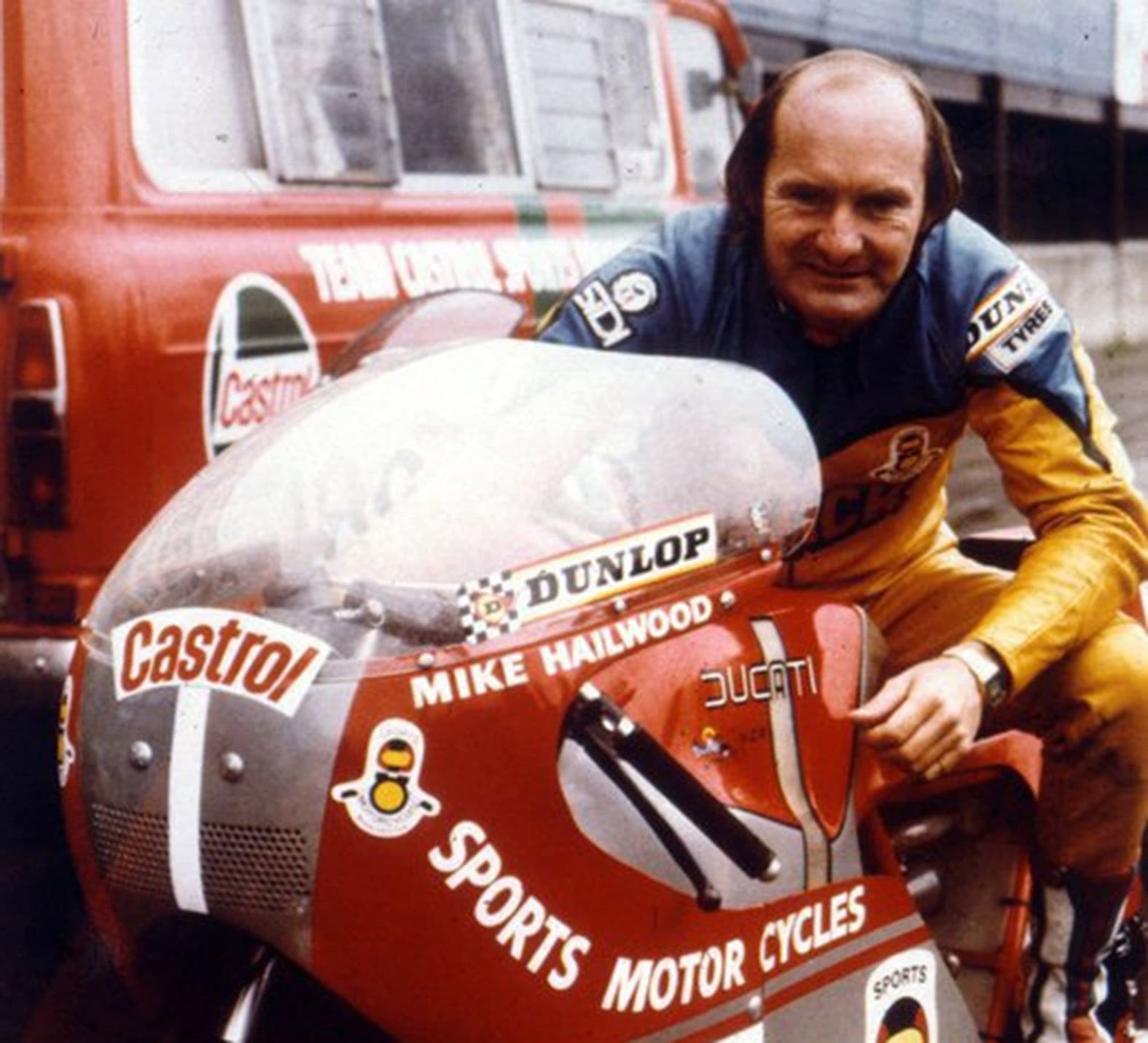

By early 1978 the word was out that Mike planned to return to the Isle of Man TT with a deal that initially involved riding an NCR Ducati for Sports Motorcycles, but which grew to include three Yamahas provided by Yamaha NV in Amsterdam. My next focus was the Easter meeting at Bathurst, but when Milledge Brothers’ Yamaha

TZ750 became available, I suggested to them that they offer it to Mike, seeing as he was due to ride one at the TT. When I phoned him in Auckland with the idea he was apprehensive at first, but called back within a day to say it wouldn’t be a

bad idea and to count him in.

A few weeks later he flew into Sydney. I picked him up from the airport, and we drove out to the meeting together in my ute, since the Bathurst organisers, ever the benevolent and far-thinking lot, refused to assist with expenses for accommodation or a hire car – not even for the world’s most accomplished motorcycle racer and a nine-time world champion. Once again, in stepped Owen Delaney, who paid for a motel room for Mike out of his own pocket.

The weather at Bathurst was absolutely foul, and the TZ750, which was a handful in the dry, was near-lethal in the wet. Mike said to me after practice that it “scared him shitless”. Fortunately it was dry for the main race, the Unlimited Australian Grand Prix held over 30 laps or 180km, which meant a fuel stop for most of the field. At least Yamaha could see the value in having Mike on one of their machines, and flew in three special, huge 36-litre fuel tanks that were allocated to him, Warren Willing and Murray Sayle to allow their bikes to complete the race distance non-stop.

It was a mixed blessing, because both Warren’s and Mike’s tank sloshed fuel out all over the rider when full, and Mike’s Yamaha refused to run cleanly until the plugs were changed in a lengthy pit stop. After practice, he told me that he was getting a rush of air up inside his helmet on Conrod Straight, so he pinched a hand towel from the motel and taped this to the bottom of his helmet. In the race the towel flapped itself to bits, filling his eyes with bits of cotton thread. Nevertheless, he soldiered on to finish ninth, a few laps behind the winner Hideo Kanaya on the works OW31 Yamaha, but this wasn’t good enough for the fickle British press, who ran the headline ‘Hailwood humbled!’ By contrast, I had a good weekend winning the 750 Production race on the Ducati with a new lap record.

Soon after it was time to mount the faithful Ducati once more for the Adelaide Advertiser Three Hour Production Race, but if the Castrol Six Hour Race had been a dream, the South Australian event was a nightmare. It began well enough with a round of social engagements and interviews, and the local Ducati fans turned up in their thousands to see Mike. Adelaide International Raceway was a strangely designed track that used a partially banked oval combined with a conventional road circuit, which was dead flat. The trickiest part was where the oval’s high-banked final turn met the main straight. It was here during Saturday’s qualifying that I banged the Ducati’s right-hand exhaust pipe on the deck, lifting the front wheel off the track and sending bike and rider crashing through the hay bales and into the concrete fence behind. I knocked myself around quite a bit, although nothing was broken, but the bike was a mess and looked like it would be a non-starter.

However, that was clearly not an option for the members of the local Ducati club, who descended upon the wrecked Snack/Moreparts entry and soon had it stripped back to the chassis, which was then hustled off to Andrew Wilson’s workshop in Adelaide where it was straightened out. In the meantime several members pulled bits off their own bikes and by midnight our machine was a runner again, albeit not quite in the immaculate state it had been a few hours earlier.

Nevertheless we lined up for the race, this time determined to make it through with a single pit stop. My first problem was simply to manage to run across the track for the infernal Le Mans start. Once again the Ducati responded to the kickstart instantly and I got away with the main bunch, but under heavy braking for the first corner at the end of the long main straight, the forks bottomed out and the front wheel locked. Instinctively I released the brake and somehow made it around the corner, but something was clearly wrong. The next lap almost the same thing happened but this time I was ready for it, albeit braking miles earlier than usual to avoid bottoming the forks. It wasn’t until after the race that we discovered one fork leg had not been filled with oil during the rebuild.

The refuelling strategy went out the window when the bike started to run out of fuel at about 88 minutes, and I spluttered around to just complete the lap and get back to the pits. In the changeover to Mike I yelled, “This thing is buggered, the forks don’t work!” he jumped aboard and yelled back, “I can see that, I’ll just go out and have some fun.” And that’s exactly what he did, to the delight of the crowd.

In his inimitable style, Mike would motor high up on the banking and ride the top line in a perfect arc, then swoop down the banking and onto the main straight miles quicker than anyone else. On one such swoop he rounded up young Ron Boulden who was on a 900SS Ducati and slapped him on the backside as he rushed past! Graeme Crosby was having troubles of his own and when Mike caught him they exchanged grins and began a battle that had the crowd in raptures. Once again, the Ducati ran out of fuel with just three laps to run, and Mike had to pit again as the leaders started their final lap, which dropped us back to ninth at the finish.

Mike had bought a two-litre glass flagon of local white wine with a ring on the neck so you could hold it with one finger and during the post race revelry he wandered around with it on his shoulder, drinking through a plastic tube, telling everyone it was the greatest invention ever. While we were having a good time, Neil was hard at work dismantling the Ducati and returning parts to the owners so they could ride home.

In 1978, Mike returned triumphantly to the Isle of Man where he scored his 13th TT win in the Formula One race – somewhat luckily as the Ducati stripped a bevel as it passed beneath the chequered flag. I was lucky enough to ride with him again in the 1978 Castrol Six Hour, and the 1978 and 1979 Adelaide Three Hour.

Just two years later, Mike was gone, killed in a road accident with his daughter Michelle. Mike’s leathers from the ’78 Six Hour hang in my office, and 40 years on, it all seems rather surreal. As Vincent Tesoriero said to me at the time, “You’re the luckiest bloke since Ringo Starr.”

By Jim Scaysbrook