Ask people to name five classic British motorcycle marques and a few names will invariably come up. Triumph, obviously … Norton, of course … and Royal Enfield, even if it has now moved abroad. Thinking further back there’s BSA, Matchless and Velocette. But there’s another true classic that might not come to many minds: Métisse.

This iconic, multi-purpose motorcycle marque was founded over 50 years ago by the two Rickman brothers, Derek and Don, to further their careers as star scramblers back in the swinging sixties. After achieving dirtbike dominance with good-handling frames powered by British twin and single-cylinder motors, Métisse started producing roadbikes and actually went on to become Britain’s largest streetbike manufacturer at one point – after the demise of Norton first time around, and before John Bloor resurrected Triumph.

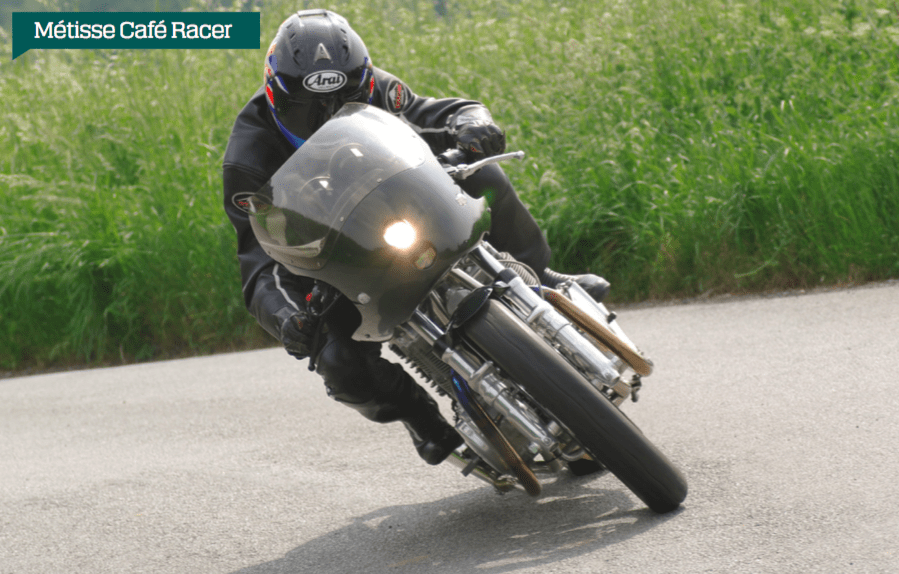

Today, the company is owned by Gerry Lisi and operates from a 270m² factory in Oxfordshire, itself set within the upmarket Carswell Country Club estate complete with 18-hole golf course that is Lisi’s main business. And it is in this factory that the Métisse air/oil-cooled DOHC eight-valve engine has been created and developed to be ready for production. This is something of a departure for the company – in the past it has specialised in producing a range off-road chassis powered by third-party engines, most notably replicas of movie star Steve McQueen’s favourite bike: the Triumph Métisse desert racer.

But after taking over the business in 2001, Lisi made plans to develop a range of modern Métisse motorcycles, including streetbikes. Only one thing was missing – he needed an engine to do it with, preferably a parallel twin, because that’s what the Métisse DNA dictated. Métisse frames had always used other company’s proprietary engines, but he needed a modern motor to meet today’s emission norms. The obvious candidate was Triumph’s then newly launched Bonneville’s 790cc powerplant, so Lisi contacted John Bloor late in 2001 to seek supplies. And despite promising signs and an initial agreement, the deal did not eventuate. “So I decided to create my own engine to produce a modern Métisse,” Lisi says. “You could say this engine only exists because of Triumph!” So, starting in 2003 with a clean sheet of paper, Lisi set out to pen his own Métisse engine, still using the same parallel-twin DAHC eight-valve format with traditional British 360-degree crank (so, both pistons rising and falling together) as the Bonneville had back then, but measuring 98 x 66mm for a full-litre capacity of 997cc. This produces considerably more power as well as torque than the Triumph engine, and is much more compact, as well as air/oil-cooled, rather than liquid-cooled like the Bonneville. “I don’t want to take Métisse too far into the future immediately,” says Lisi. “It needs to catch up with itself, which means going air-cooled first to maintain a link with the past and the retro bikes we’re building now, but then in the future we can produce a higher-performance liquid-cooled version, if needs be. The basis is there.”

Of course developing an engine takes time, as Lisi goes on to explain. “The actual design was done quite quickly, but then I brought in a company to transfer it on to CAD, and that took a while. The first Métisse 8V engine came together in November 2008, and when it ran on the dyno we were very pleasantly surprised. It was, thankfully, dead right first time – a hole in one, as they say in our clubhouse! But that was a billet motor with sandcast crankcases, and most other key parts carved from solid metal. What delayed putting it into production until now was that I’d exhausted most of my capital actually developing the engine, and production of the McQueen replicas that provide the cash to underwrite the development fell right away when Triumph produced its own McQueen Bonneville. It was less expensive than the hand-built Métisse Desert Racer, even though it was a lot less authentic – clever marketing made it a bona fide bike to a lot of people who didn’t really know better. But that’s been and gone over three years now, so demand for the ‘real’ McQueen bike has stepped up again in the past six months, and we now have more than 30 orders to meet. This has given me the cash flow to productionise the eight-valve engine by making the necessary patterns to diecast the components.”

Métisse is now offering customers a choice of either the Café Racer or Street Scrambler models at a price of GBP 25,000 (around A$44,000) plus tax, with an extra GBP 1000 (A$1750) for the half-faired version of the Café Racer. Delivery time is four to five months at present from the time an order is placed, but Lisi aim to get that down to two or three months once series production gets properly underway.

The meaty-looking, yet surprisingly compact Métisse engine is housed in an all-new Mark 5 nickel-plated chrome-moly duplex cradle frame with neo-classic looks and is identical for both models. These carry a completely non-adjustable 41mm Ceriani fork set at a rangy 28° angle, with twin fully adjustable Öhlins shocks at the rear, operated on the Café Racer by a tubular steel swingarm which is 20mm longer than the rectangular-section one on the Scrambler, resulting in a 1500mm wheelbase and a little more weight on the front wheel for extra grip in turns. Tubeless Avon RoadRider tyres are carried on the wire-spoked Alpina alloy rims – the front a 19-incher, the rear 17-inch. The Brembo brake package is a serious one, with twin 320mm front discs and four-pot calipers (not radial ones, though) matched to a 220mm rear gripped by a twin-piston caliper. These haul down a bike hard that weighs 181kg with oil, but no fuel in the 18-litre hand-beaten aluminium fuel tank.

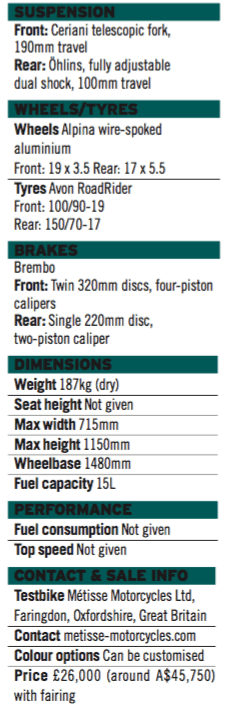

I’d already had the privilege of being the first outsider to test ride the prototype Métisse Scrambler back in 2011, before the project was put into cold storage when funds dried up, and had been seriously impressed by its potential. This time around I was on the brand new Café Racer, and headed out into the verdant Oxfordshire countryside on a glorious early summer day to compare and contrast it with the Scrambler, as well as to try to ascertain if it had $45,000-worth of appeal, quite apart from the historic Métisse name on the gas tank.

Straddling the 750mm-high seat, it was immediately obvious that this is one B-I-G motorcycle, best suited to those of Gulliveresque stature. At 180cm, I was only just able to stretch far enough out along the long, broad fuel tank (so bulky it completely hides the engine from view) to grasp the low-set clipons mounted beneath the upper tripleclamp; anyone much shorter would have a hard time getting comfortable on the half-faired Métisse. Against that, the seat is plushly upholstered and the footrests are ideally placed – it’s just that the bike seems too long. It’s spacious without being welcoming.

But just thumb the starter motor and you’re immediately entranced by what has to be the single most distinctive engine note on today’s highways. This emerges from graceful twin separate exhausts, which are at no stage connected as they follow the line of the frame rails in heading rearwards towards their slender megaphone silencers. The Métisse engine’s rorty exhaust note is unmistakeably British, an authentic modern take on a traditional two-up parallel-twin of all our BritBike yesterdays – not one pretending to be a 90º V-twin via a 270º crank as comparable designs from other marques in the UK do today. Even in semi-muted form via an attempt at road-legal silencing, the 8V Métisse sounds like a swarm of angry hornets when you rev the engine hard under acceleration, with that trademark flat droning exhaust raised several octaves compared to a 70s-style Norton Commando or Triumph Bonneville. It’s utterly addictive.

Equally so is the 8V engine’s performance, even if at the moment it’s pretty understressed, with an 8500 rpm revlimiter for a powerplant that Gerry Lisi says was designed to be safe well into five figures. Indeed, camshaft supplier Piper Cams reckons it could deliver over 100kW with suitable tuning – bring it on, Gerry! In its present state of tune it has been dyno tested to produce 72.3kW at 8000 rpm at the gearbox, around 40 per cent more than its putative Norton and Triumph parallel-twin rivals.

Its extremely flat, meaty torque curve combines with a totally linear build of power to deliver good acceleration. But what most impresses you about the Métisse motor is how very flexible and forgiving the engine is –Lisi had been considering the expense of developing his own six-speed gearbox for the bike, but it’s honestly not necessary. On top of that, the 8V engine is totally and utterly smooth all the while it’s still busy building power. There’s no trace of tingles at any revs through the seat, footrests or handlebar, making this a traditionally British two-up parallel-twin that’s smoother than most fours. That’s quite a trick!

The Café Racer drives forward at part-throttle from just off its 1500rpm idle speed (perhaps deliberately set slightly high, to counter the fact it has no slipper clutch?) with no transmission snatch thanks to the smooth pickup from a closed throttle delivered by the Australian-made MoTeC ECU. Gear shifts are crisp and precise without being especially smooth – there’s a mechanical sense of each gear going in which is actually quite satisfying, and I never missed a gear once during my afternoon riding the bike. The cable-operated Triumph clutch is lighter and smoother in operation than it was before on the 8V Scrambler, so that’s been improved without yet switching to the hydraulically operated AP clutch which is still on the cards.

So the Métisse 8V has a great sound, oodles of torque, zero vibes … but now for the best part: the way it catches fire from 3000 rpm upwards. The MoTeC has been really well mapped by someone who knew what they were doing, with extremely good fuelling at all revs. The Métisse accelerates strongly from low down, with a great top gear midrange roll-on thanks to the hyper-horizontal torque curve. This in fact discourages you from revving it out, because the muscular midrange is so strong you can just short-shift at 6000 revs, and the engine keeps on pulling hard without needing to go anywhere near that low-set revlimiter. Sounds great if you do that, too!

The Café Racer is now geared better than the Scrambler was – taking three teeth off the rear sprocket has made it longer-legged without sacrificing performance. It also fires up better from cold than the Scrambler did, which spluttered and died first time of asking before lighting up properly second time around. Throttle response at low revs is also no longer hesitant. There’s a clean, strong pickup from a closed throttle without it being jerky or over-aggressive. This is simply a very nice bike to ride, thanks to that fabulous engine which still has massive reserves of potential if Gerry Lisi chooses to exploit any of it in the future.

The new Métisse handles reasonably well in spite of the conservative steering geometry, very similar to the 1974 green-frame Ducati 750SS that I ride today in Classic F750 races. This is super-stable on fast sweepers, but you need to send it a telegram to change direction in tighter turns. The Métisse 8V Café Racer is similarly lazy-steering, made all the more so by the 19-inch front wheel –a step too far along memory lane in my opinion. There’s no reason why this motorcycle shouldn’t have 17-inch rubber front and rear, or at the very least an 18-inch front. Ground clearance isn’t an issue, because I only kissed the tarmac very lightly with the right exhaust cranked hard over at full lean. A smaller front wheel would speed up the steering.

While he’s about it, I think for such a high price tag Gerry Lisi must install fully adjustable front suspension on this motorcycle, whether from Öhlins or WP, even if I was relatively happy with the Ceriani fork’s compliance over the sometimes bumpy tarmac of Oxfordshire country lanes. The fully adjustable Öhlins rear shocks, however, hadn’t yet been set up properly yet, and it showed. They were much too stiff and sent the rear end leaping around over the road rash. A serious sort-out session would fix that.

While he is already satisfying orders for Scramblers, Lisi is aware that the Café Racer needs further work to make it fully customer-ready. The biggest issue is its architecture – it needs to be shrunk slightly to make what is undoubtedly a great-looking motorcycle capable of being ridden comfortably by a wider range of potential customers than at present. This will involve subtly redesigning the chassis to shorten the reach over the fuel tank and especially to narrow the frame behind the tank between the rider’s legs. Lisi is already planning to give away a couple of litres and shorten the fuel tank, which will surely help close things up a little. But given that each bike will be tailor-made for the customer buying it, if you happen to be a 195cm basketball player, you machine could already be here. It’s a neo-classic ride with reserves of real world performance.

Praise is due to Lisi for bringing Métisse back to life through the creation of that wonderful, practically flawless yet ultra characterful parallel-twin engine. Its development represents a remarkable achievement for a company that never before made its own powerplant. So how about that 1100kW Café Racer engine, Gerry? Lisi chuckles: “I think that’s all for the future, and something we’d do with a liquid-cooled engine,” he says, “same as a more modern Desert Rally model, with a monoshock rear end and a lot more suspension travel. But we want to start off with this kind of retro-inspired bike, which appeals to our traditional Métisse customer who’s looking for something more modern than a true classic like our McQueen Desert Racer replica, but not too modern. We want to stay true to our roots – it’s early days yet, but having finally reached the stage of starting production, I feel we’re on the right road.”

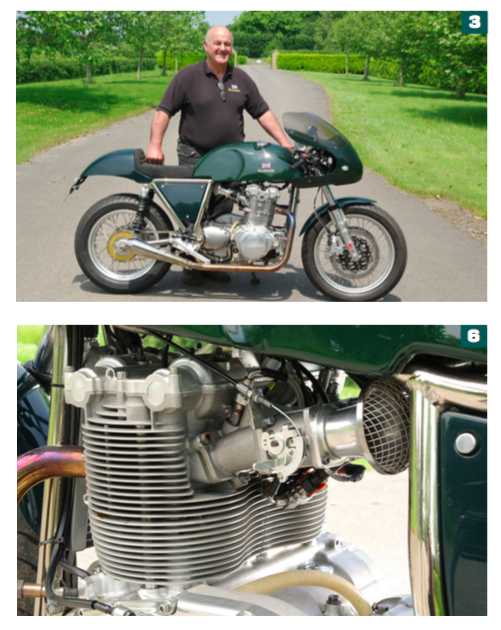

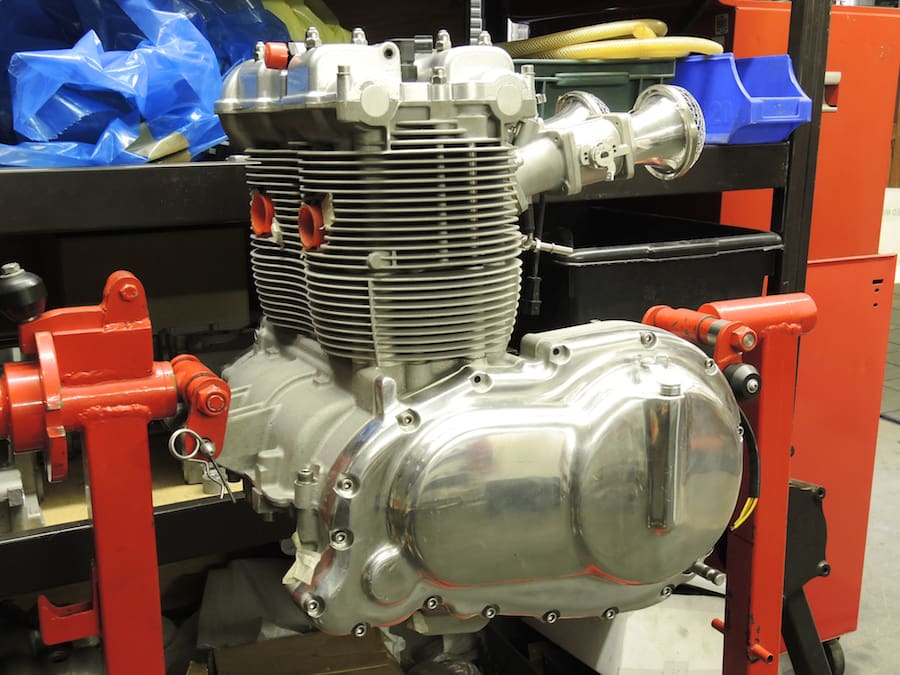

The Métisse mill

Lisi decided to optimise heat reduction on the air/oil-cooled Métisse 8V by placing the cam drive on the right side of the engine in order to create a gap between the cylinders to fully cool them all the way round, and also wrapping an oil jacket around each piston to help achieve this. This entails placing the twin counterbalancers inboard, centrally located at the front and rear of the horizontally-split crankcases, and gear-driven directly off the centre of the crankshaft.

The cranckshaft is an Arrow Precision one-piece EN40B billet steel unit with shell-bearing big ends and four main bearings, which carries Arrow steel conrods fitted with Capricorn three-ring pistons delivering 10.5:1 compression – the Métisse 8V engine will run on regular unleaded fuel.

The gas-flowed eight-valve cylinder head has a good amount of squish, with paired 37mm inlet and 32mm exhaust valves, each with dual coil springs and operated by specially-designed Piper cams via a modular drive system. This sees an intermediate gear running directly off the crank on the right of the motor, driving a short chain which runs to another idler pinion, off which the twin overhead camshafts are themselves gear-driven.

Twin 42mm JVC throttle bodies are used, each with a single Ford Mondeo car injector positioned just south of the butterfly and controlled by a MoTeC ECU. The unit construction engine employs a 5-speed Triumph transmission, with a Bonneville clutch and gear primary drive, off the back of which the twin oil pumps are driven.

Two-wheeled Karma

When the Rickman brothers began their bespoke bike business, manufacturers like BSA, Triumph and Norton gave them short shrift. But those big companies would suffer a reversal of fortune.

“The British factories were completely uninterested in what we were doing, and would never supply us with anything,” says Derek Rickman. “I mean, not wheels, not forks, nothing – not even with cash on delivery, and not even after we’d become established, and to be honest, successful. But you know, when we built the first Métisse frame in my back bedroom and got it running, it seemed a very good frame, so we took it in turn to Triumph, Norton, BSA and Matchless – all four of them – and tried to get each of them to evaluate it with a view to taking it on. We were prepared to give them the design free of charge, all we wanted in return were bikes to race with ourselves. We didn’t want any money for it. We must have been very naïve to give it all away, even being racers. You wouldn’t ever try and do a thing like that these days, would you?!

Anyway, they all turned us down flat, and that’s what made us into manufacturers, because at that time we were retail motorcycle people, and we had no idea about building bikes ourselves. But when they all turned us down, it quite frankly annoyed us, so we said, “Right, we’ll make them ourselves!” And then within 20 years, of course, they had all gone, and we were the only ones left in the country building motorcycles. What do you make of that?!”

By ALAN CATHCART PHOTOGRAPHY KYOICHI NAKAMURA