The past decade has seen an exponential increase in the availability, performance, range and recharging speed of electric-powered two-wheelers – but also in their price. EV Euro-leader BMW charges each US customer for its C-evolution E-scooter a hefty US$14,895 (AU$20,863) for the entry fee to the owners club, while an American-made Zero SR is listed at US$16,495 (AU$20,104) for the base model and Harley-Davidson’s upcoming 2020-model LiveWire will be priced at US$29,799 (AU$41,742). Turns out saving the planet ain’t gonna be cheap…

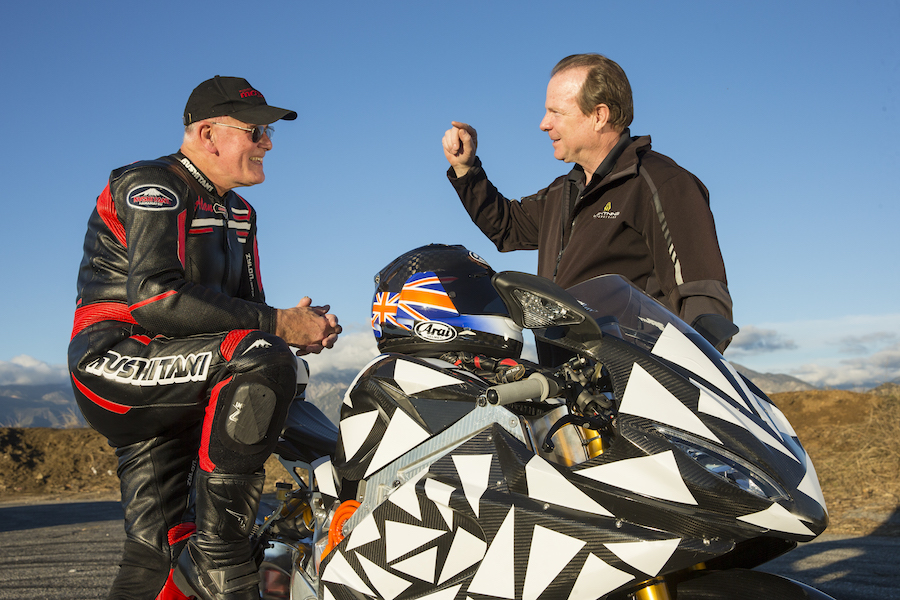

Lightning Motorcycle Corporation Founder and CEO Richard Hatfield, 60, has been building E-Superbikes for longer than anyone else, and he’s achieved more with them in the white heat of competition than any of his rivals, too – up to and including coming out on top in a direct matchup against internal combustion-engined sportsbikes [see sidebar].

For the past five years his Californian company has marketed hand-built LS-218 roadbikes based on the Lightning which currently owns the World Land Speed record for electric motorcycles, and which 40 have been built so far for delivery to customers as far afield as South Africa and Guam, though most have been sold in the USA, with several orders in the pipeline. Purchasers have a choice of three 380V battery packs powering the LS-218’s 149kW (200hp) electric motor. The cheapest 12kWh base version gives a 160km range, while the mid-range 15kWh version manages 190km, and the 20kWh model 240km, all claimed figures for highway riding conditions at legal speeds. Price-wise, they start at US$38,888 (AU$54,472), rising to US$46,888 (AU$65,678) for the 20kWh model. So while undoubtedly delivering impressive performance and mega-exclusivity for the money, so far the Lightnings have very much followed the E-biking norm in terms of pricing.

But now, Hatfield is preparing to step outside that financial comfort zone, and make electric motorcycles fully competitive in terms of performance as well as pricing.

He’s doing so by launching the Lighting Strike, a 600cc equivalent to the LS-218 Superbike which, while still delivering sports styling and appealing performance, will start at US$12,988 (AU$18,193). That’s with slightly less than half the horsepower of the LS-218, namely 70kW (96bhp) at 15,000rpm at the output shaft of its liquid-cooled 150V three-phase AC induction motor made entirely by Lightning, with a liquid-cooled inverter/controller, rising to 90kW (120bhp) from the more powerful 300V version that’s also available at a higher but yet-to-be-revealed price. Both versions deliver a constant 95Nm of torque available from 1rpm, and are powered by Lightning’s own battery packs using imported pouch-type lithium-ion cells, with an integrated thermal management system, and real-time data collection for managing the state of charge and state of health of each individual polymer cell.

The Strike’s range is claimed to be almost 200km in an urban cycle with an 18kWh battery pack, and in the 120-140km range at highway speeds, while Hatfield insists that recharging time from five percent to 95 percent can be under 40 minutes with a DC charger. Claimed weight is 206kg with all cooling fluids, 20kg less than the LS-218, split 52/48% along the Strike’s 1420mm wheelbase. And yes – Hatfield did have to pay Harley-Davidson a release fee to use the Lightning Strike name formerly registered to its defunct Buell brand. “It was more than we wanted to pay,” he says, “but not as much as I was fearing!”

Hatfield’s on the money, literally, when you consider a current-model Yamaha YZF-R6 costs $12,199 in the States and he says the Strike’s retail price is only feasible because of the complete restructuring of his company, including the opening of two new 1858m² factories. The first is in the heart of Silicon Valley in San Jose, California, and is five times larger than Lightning’s previous base. The other is in China, close to the QJ Benelli and KTM-CFMoto plants, as well as Moto Morini’s new owner Zhongneng.

“We know we must be able to build these bikes at a competitive price and in a kind of volume that will allow Lightning to compete with gasoline bikes on price,” explains Hatfield. “We’ll do the engineering and product development in California, but will manufacture the majority of the parts in China before shipping them to the USA, where we’ll assemble bikes destined for North America, and certain of our export markets. Then we’ll ship each motorcycle as a CKD/complete knockdown kit into our US dealers and our distributors in other countries, where they’ll hand assemble them locally.

We’ll also build complete motorcycles in China for certain markets where it makes sense to do so geographically – not only China itself, which we see as a key market for Lightning, but India in particular. China is definitely going to be one of the biggest markets for electric motorcycles as opposed to scooters in the next few years, but we think India will be right there with them, basically to address the environmental problems that they face at present.

“Together, the two largest motorcycle markets in the world will both predominantly focus on electric motorcycles in coming years, and Lightning will be there to serve them.”

The Strike is scheduled to be unveiled in March, with production of complete motorcycles to satisfy what he says are the many sight-unseen pre-orders Lightning already has for the bike, starting in June. Its debut will thus be the opening roll of the dice for a proven strategy which however has never yet been applied to the motorcycle industry.

Having spent a pretty thrilling as well as illuminating day four years ago aboard the deeply impressive LS-218, my opportunity to become the first person outside Lightning to ride the prototype Strike came one of the Los Angeles basin’s glorious motorcycle roads, whose steep inclines and switchbacks provided a stern test of handling and especially torque. And even in raw, undeveloped form, the Lightning Strike didn’t disappoint.

However, at this stage in its development cycle, the prototype was based on the architecture of the LS-218, with essentially the same chassis package including brakes and suspension, as well as styling. This led Hatfield to insist on covering it with camouflage tape. And in five hours of riding I saw a total of 17 cars and two motorcycles, and no resulting Facebook posts meant Hatfield was a happy man.

Riding the Strike made me happy, too – even if there were inevitably several areas for improvement, mainly in the rider ergonomics. However, since I was riding what was essentially a proof-of-concept model closely based on the LS-218, there’s lots of time for Lightning to address these issues before production commences, and they must.

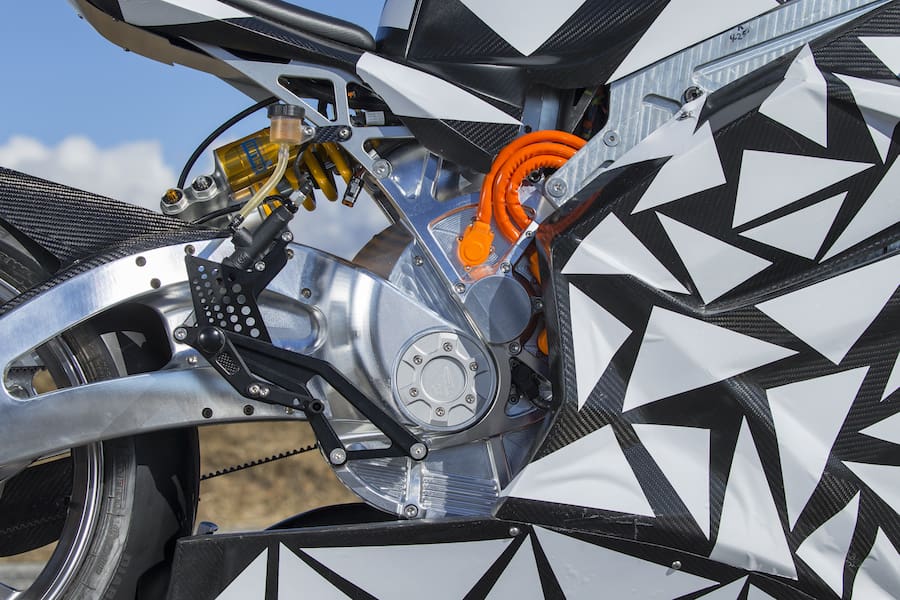

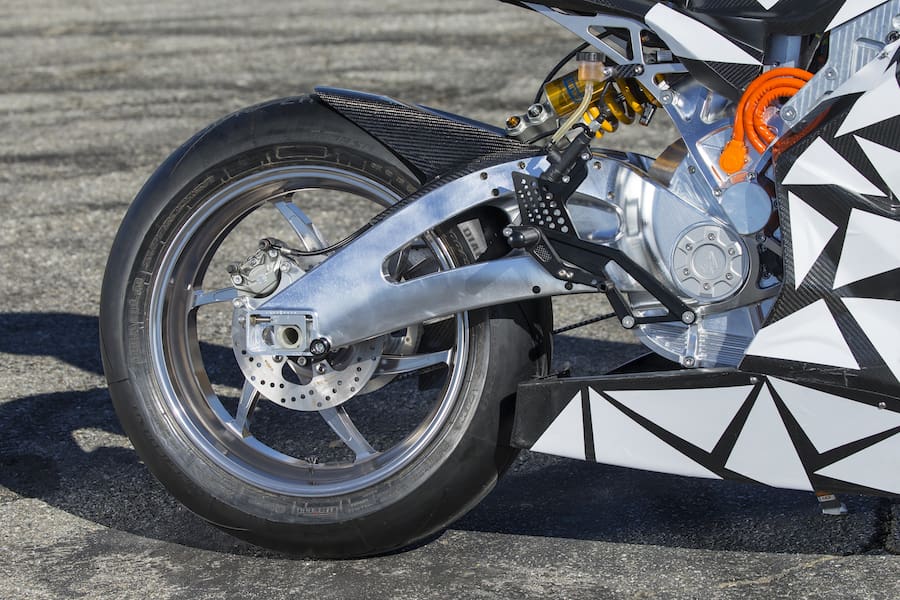

The chassis of the Strike was machined in China by the array of hi-tech CNC machines in Lightning’s factory there, and that includes the beautifully crafted swingarm machined from solid aluminium billet. I wasn’t allowed to remove the LS-218 bodywork adapted to what is a much smaller motorcycle – final styling is all-new, and the work of someone other than Glynn Kerr who created the LS-218’s looks, says Hatfield. So no chance to peer at the Strike’s array of batteries and assorted hardware – much less photograph them – though when deliveries begin Hatfield is aware he’ll have to accept exposing his technology for all to see. Meantime, suffice to say that the Strike essentially consists of an aluminium shell housing the batteries which doubles as a monocoque frame.

The prototype’s fully-adjustable Öhlins suspension will only be available on the high-end version, and priced accordingly, says Hatfield – the much lower-cost entry-level model will most likely have Showa suspension. And the top-quality Brembo brake package on the prototype is also a straight off the LS-218 and still plans to use a lower-spec Brembo package on the production bike.

Climbing aboard the Strike immediately revealed a more comfortable, more rational and certainly more welcoming riding position than on the LS-218, particularly in terms of the width of the front part of the seat and the frame beneath it. On the bigger bike this wasn’t just uncomfortable for any size rider, but meant that shorter riders would struggle to reach the ground. On the Strike however, that’s not an issue, the bike has been scaled to seven-eighths the LS-218’s overall size, and it’s immediately more congenial, even though the 813mm seat height remains unchanged. However, said seat on the Strike was too inclined, so I couldn’t help sliding forward to the rear of the faux fuel tank shrouding the batteries. Its clip-on handlebars were also set too flat (to avoid rubbing the bodywork lent to it by the LS-218), and this meant I couldn’t easily push against them to counter sliding down the seat. They need to be pulled back anyway, which would also mean less of a stretch to reach them. Finally, to complete a full critique of the Strike’s ergonomics, the footrests are far too high even with the excellent grip delivered by the Pirelli Diablo Supercorsa rubber (expect Pirelli Angel GT rubber on production bikes) fitted to the forged aluminium wheels made to Lightning’s design.

At 180cm, my legs were very cramped which not only compromised comfort, but also prevented me moving about the bike as I wanted to do in order to hustle the Strike through the Glendora bends. It also meant that I could barely reach the front brake lever, instead relying on the rear brake pedal to slow the Strike down.

These criticisms merely amount to suggestions at prototype stage, and for that reason it’s also pointless to comment on the Strike’s brakes and suspension, since the hardware carried by this early prototype won’t reach volume production. But a close look at the ergonomic triangle is needed, and Richard Hatfield realises this. However, he’s got the Strike’s essential architecture dead right – though physically smaller and with more accessible performance from the half-as-powerful motor, it feels chuckable and agile in a way the heavier and bulkier LS-218 could never be, despite sharing the same 24º rake/105.3mm trail steering geometry as the bigger bike.

But if the Strike’s chassis package needs some work, the motor is just about spot on. After booting up the bike and going live, you must be ready for the traditional Lightning arm-lengthening acceleration, so hold on tight. Acceleration isn’t as absolutely monstrous as on the LS-218, but thanks to the instant dose of substantial torque as soon as you crack the throttle, it’s still mighty impressive and far superior from a standstill to almost any other sportsbike of whatever capacity. Absolute top speed won’t be anywhere as fast as the LS-218, but that’s not the point of this real-world E-motorcycle, which represents a new departure for Lightning – away from outright performance, towards real world rideability.

“We’re targeting the 650-800cc sector of gas-powered bikes with the Strike family of models,” says Hatfield. “So this is our mid-price, mid-performance, middleweight model with half the outright power and around 18 percent less battery than the LS-218 – although we can also configure it with larger high-energy batteries for extra range.

“So we’ll have several options on that, and the same with the charger. Our base model has a 3.3kWh Level Two system which takes roughly three-and-a-half hours to charge from five percent to 95 percent, but we’ll also offer a 12 kWh charger which will reduce recharging time to roughly an hour, or a DC fast charger which brings it down to 40 minutes. We’ll be giving each of our customers the opportunity to specify the exact overall package they’re looking for.

“We’ll also be offering a Naked roadster-type Strike which we’re working flat out on bringing to market, in recognition of the fact that this will most likely be our volume seller – especially with an even lower target price than for the Supersport.”

There’s also an entry level E-bike planned for the future, equivalent to a 400cc model. But not anytime soon.

The Strike prototype delivered thrilling acceleration coupled with controllability at low speeds, and especially exiting a tight turn, with no trace of the brusque pickup mid-turn from a closed throttle of some E-bikes. The fact that the build of power, and especially torque, all the way to the 15,000rpm limiter is so smooth and linear, makes it feasible to exploit the reserves of performance of the Lightning motor. That’s thanks to the cleverly sanitised way that Hatfield has mapped the ride-by-wire throttle. While there’s quite a thrill to be had by winding the throttle wide open as soon as you get the Lightning moving, in normal riding the initial acceleration isn’t as fierce and vivid as on some other E-bikes, only coming on strong one you’ve hit about 50km/h.

“The first 50 percent of throttle movement accesses less than 30 percent of the torque,” explains Hatfield. “But then when you want to push it harder, the other 50 percent of throttle rotation – as measured by a potentiometer inside the handlebar – progressively delivers more and more torque. The software allows us to dial in the torque curve, as well as to alter the regen.”

Oh, yes – the regen. This dual-function regenerative braking is comparable to engine braking on a conventional motorcycle, quite apart from recharging the batteries and extending range. However this was too high on the Strike as I rode it, so maintaining turn speed was hard without consciously accelerating into and round the bend, and at low speeds the bike reduced momentum so abruptly it risked becoming unstable. At present the regen could only be adjusted via Hatfield’s laptop, but this is a must-have feature on the bike – just as other brands will let you adjust it, and indeed Lightning on its LS-218.

Still, this meant I could attack Glendora’s twists and turns in something approaching anger while hardly using the brakes, just backing on and off the throttle. But the Brembo brakes did their accustomed great job in slowing the Strike from high speed in conjunction with the regen, although it’ll be necessary to have ABS fitted, for European sales. It’s coming, says Hatfield. So too, I hope, will be a range of riding mode options for the Strike.

The Lightning Strike has the potential to be a game-changer in the E-bike marketplace. More performance for fewer bucks is a potentially winning formula, and Richard Hatfield deserves huge credit for creating it – but this time for his business acumen and far-sightedness, as much as for his groundbreaking engineering that’s already been rewarded on the racetrack.

I’m looking forward to sampling the finished version, where performance and allure are combined in a single price-conscious package.

Record pace

Since building his first electric motorcycle over a decade ago, Hatfield has set the pace. In 2006 he acquired an Yamaha YZF-R1, sourced large format lithium batteries and matched it all to an industrial AC three-phase induction motor and drivetrain. With around 50kW and 94Nm of torque, it was geared for a top speed of 160km/h and would go over 100 kays on a single charge.

“At that point nobody else had made a lithium battery EV sportsbike,” says Richard with a hint of pride, “and we decided to immediately start building one that was better.”

He sourced a motor from an electric car and built a chassis around it, and sourced newer technology and higher power batteries that were already pouch-type cells, not the cylindrical batteries most other people were using.

“We finished it off in 2009, then took it to Bonneville and ran over 166mph (267km/h), though we did not break the World record. The next year, 2010, we raced in all the TTXGP road races in the USA, starting at Infineon where we came second with some handling issues. But then we won all the other races and the championship, sometimes even lapping the second-place bike.

So then we took it to Bonneville and we did break the record that year, which was pretty satisfying because we were running against the Isle of Man TT-winning MotoCzysz. We got the official FIM world record at 173.388mph (279.0409km/h), with a one-way pass at 176.044 mph (283.315km/h).”

On the gas

The Lightning also won the FIM World Championship round run as a support race for the Le Mans 24-Hours with Miguel DuHamel, and after another visit to Bonneville where he broke his own record by almost 40mph (65km/h), with a one-way pass of 218.627mph (351.846km/h), Hatfield had just a single visit to Pikes Peak in 2013 to demonstrate the bike’s effectiveness against combustion-engined products.

The LS-218 defeated all conventional motorcycles taking part to win the 2013 Pikes Peak hill-climb outright, with rider Carlin Dunne clocking a time of 10m0.964sec, almost 20secs ahead of the best of the petrol-fuelled rest, which happened to be the factory-supported Ducati Multistrada – a fact which somehow got omitted from Ducati’s official press release, which gave the impression it had won the race outright. Tut, tut.

Test Alan Cathcart Photography Kevin Wing