He’d made Western Australia in barely three insane days but by the time he reached Port Hedland he was out of his mind. In a successive series of mishaps he speared the Honda into a deep table drain, taking over three hours for the extraction, then after a quick but necessary kip at a truck stop rode 400km in the wrong direction. Then the really sick hallucinations commenced. Despite it all Van Straten rode back into Sydney in less than eight days. But Atkin’s record held.

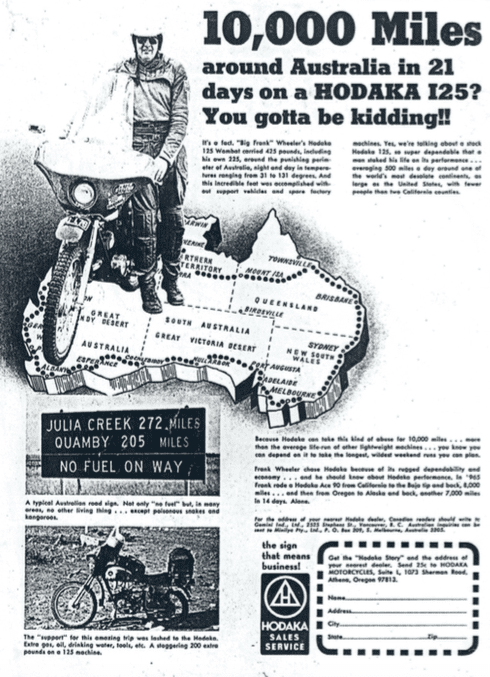

You gotta be kidding! So read the headline on the Hodaka ad celebrating Frank Wheeler’s 10,000-mile trek around Australia. Frank Wheeler wasn’t the first motorcyclist to complete a lap of Australia, however, as most of his fellow Hodaka fanatics in California would have placed Australia somewhere between Switzerland and Germany, few would argue when in December 1972 he claimed to be the first rider to encircle the strange island full of kangaroos, emus and crocodiles.

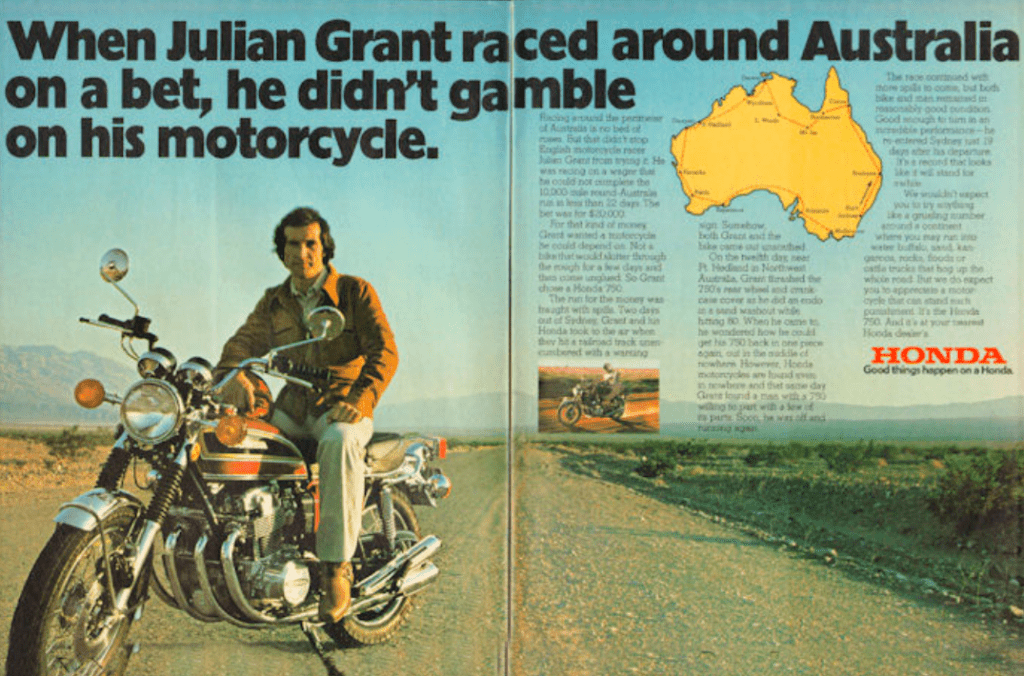

Here in Australia, Wheeler’s exploit went largely unheralded, yet an enterprising copywriter on Madison Avenue saw the perfect concept to promote the new Honda CB750. A $20,000 bet was made – allegedly between Wheeler and British bike racer Julian Grant – that Grant couldn’t ride around Australia in less than 21 days. Wheeler later claimed there was no bet, but by that time he was outgunned by Honda’s USA-wide advertising campaign claiming a new record of 19 days, even though Grant took a shortcut.

Aussie adventurer Chris Peckham didn’t give a stuff about all this transatlantic rivalry when he rode his Honda XL125 around Australia in eighteen and a half days – including three days spent in Dubbo hospital. Now Dubbo is nowhere near our coastline but, in order to avoid as much bitumen as possible, Peckham’s route took him through Broken Hill, bypassing Victoria entirely. Lest he too be accused of taking a short cut, Peckham made up the distance somewhere else, returning to Sydney with 16,206 kilometres on the Honda’s odo.

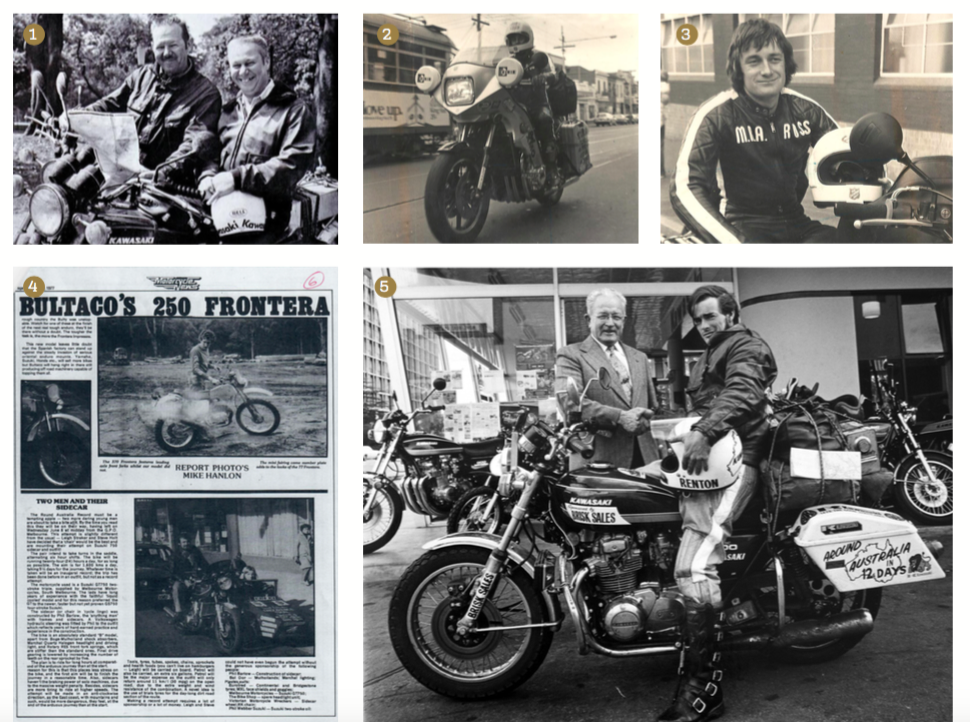

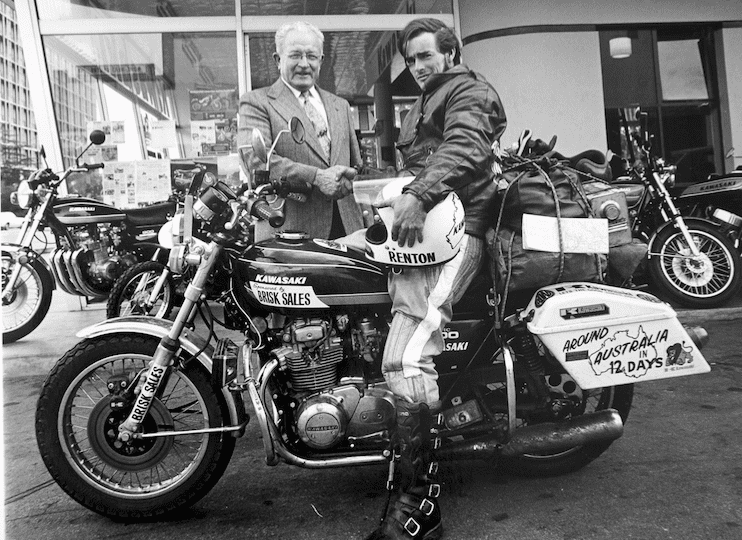

Only months later, in the dead of winter 1974, Barry Renton overcame severe hypothermia when he raced around the continent in less than 15 days. Suzuki claimed Renton’s GT550 had been faultless over ‘almost 1000km a day’. We’ll never know whether, like Julian Grant, Renton cut off the loop through Albany on the far southwest coast, but it mattered not. On 24 October of that year, St Louis Kawasaki dealer Rich Willey and his mate Don Kerr had their logbooks stamped in Sydney before heading up the Pacific Highway on a pair of 900cc Kawasakis. Sixteen days and 10 hours later they returned via the Princess Highway, scores of signatures in their logbooks and 16,653km on the Z1 odometers. Amid great publicity, they flogged the Kwakas a second time and headed back to St Louis.

In addition to irrefutably claiming the record, the two Americans ratified Wheeler’s route. Unofficially, any further claimants to the record would, with the exception of the goat track to Borroloola, follow Australia’s National Route One in its entirety. This included the ‘sometime’ dry weather only gravel section between Cairns and Normanton and the horror stretch in Western Australia between Halls Creek and Derby.

Aspiring Sydney racer Shane McLachlan, figuring a hot lap of Oz might result in some publicity for his track activities, took off South in early 1975. Though his Honda XL350 may have got the job done, traversing Australia’s tropics only months after the devastation wrought by Cyclone Tracy proved impossible. He returned to Sydney after a hallucinogenic 36-hour stint from Townsville. Ignoring the pink elephants in the 21-year-old’s eyes, Constable Lill of Grosvenor Street Police Station provided the final signature in McLachlan’s logbook. McLachlan got his publicity but not the record.

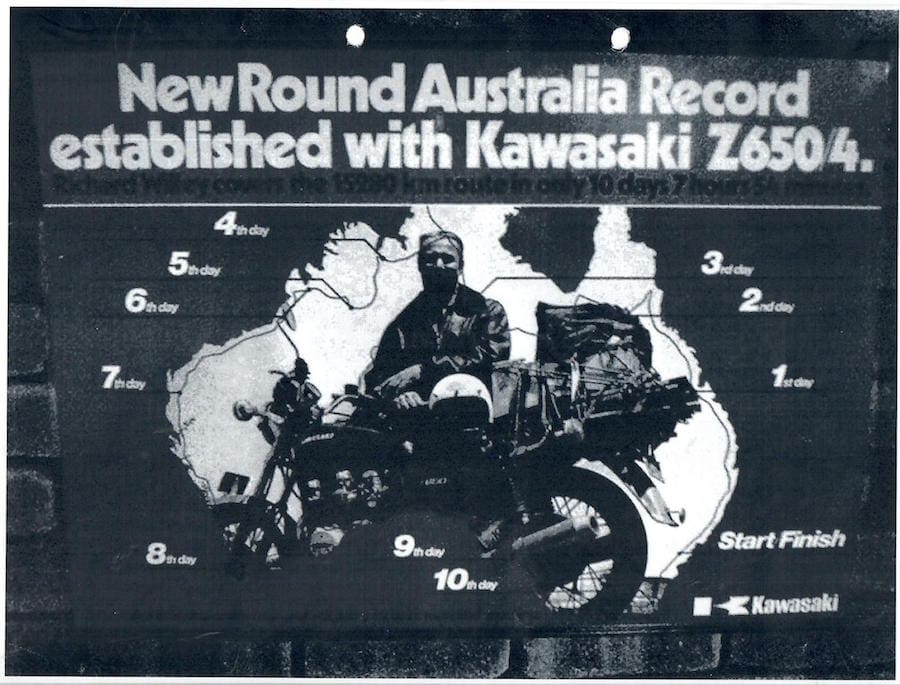

Newspaper reports suggested otherwise, which got under Barry Renton’s skin, and in October 1975 he turned up the wick on a Kawasaki KZ400, setting a new benchmark of 10 days and nine hours. On reading this, the Americans Willey and Kerr were soon back in Sydney. It being the second lap for these blokes they knew the form, and even the rugged track between Georgetown and Normanton didn’t delay their Kawasaki Z650/4s. When Kerr requested the Darwin police sign their log books they commented that “Only a couple of yanks would do such a cock-a-mamie thing.” More like “You f***ing septics are lunatics.”

Kerr’s ride came to an end when the front tyre blew crossing the Kimberley. At Derby hospital they agreed that Willey should continue. His final stint from Ravensthorpe in southern WA to Sydney set an average speed of more than 85km/h, passing unhindered through Adelaide, Murray Bridge, Mount Gambier, Geelong, Melbourne, Nowra and Wollongong. This can only be explained by the fact that this was the same month that colour television was introduced to all four channels.

If the Americans believed their record would hold they were sadly mistaken. Though months passed without a new record being claimed, a bloke named Mal Price made an unsuccessful attempt on a brand new BMW R100/GS. In an earlier attempt, Price had blown a tyre on the Barkly Tableland, the resulting accident putting him in hospital with massive shoulder injuries. This time round, an overtaking manoeuvre on the Atherton Tableland went horribly wrong, and Price proved conclusively that 130km/h was a touch fast when the advisory speed sign recommended a mere 40.

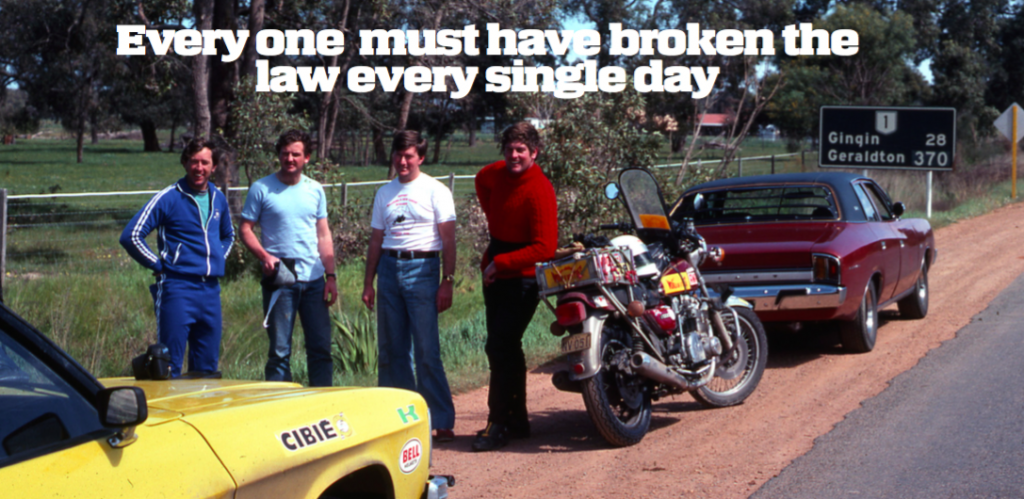

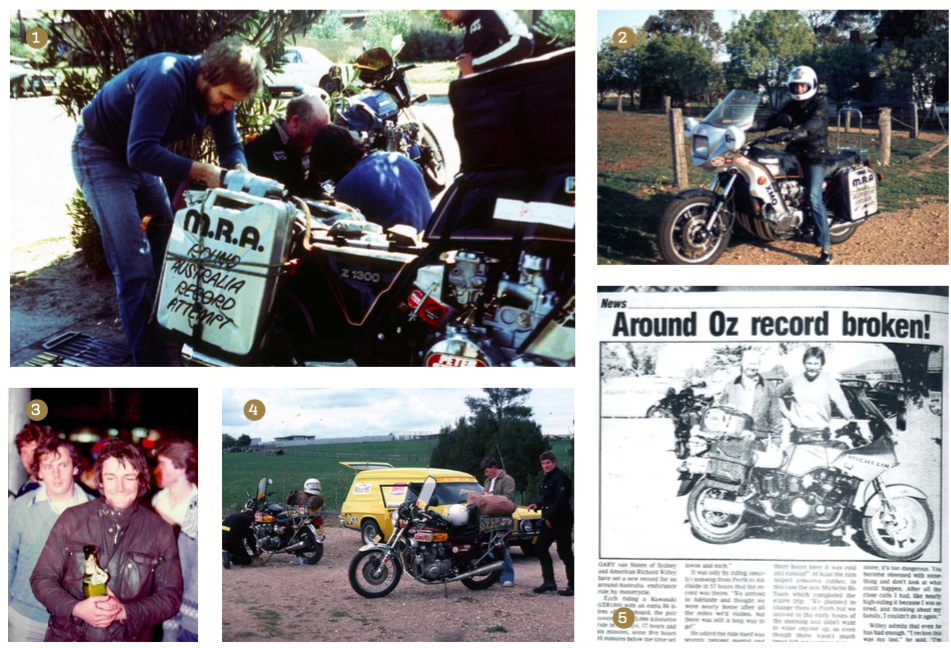

Speed signs of any kind were totally irrelevant to the next contenders: Constables Warwick ‘Whacker’ Schuberg and Graham Forlonge of the NSW Highway Patrol. Endorsed by NSW Police Commissioner Mervyn Wood, hyped across Australia on national radio by the golden tonsils of John Laws, sponsored by Kawasaki – with a pair of specially prepared Z1000s – and Holden – with a bright yellow V8 panel van – there was nothing undercover about this operation.

Support driver Steve Smith contends that, monitored closely by local media right around the country, they stuck rigorously to the 60kph and 80kph ‘built up’ speed limits; but out on the open highway speeds often approached, and sometimes exceeded, the ‘double ton’. An untightened oil filler cap ended Schuberg’s run, but Forlonge was well inside the record when he stopped in Kempsey, saying ‘Can’t do it’. Pushing Forlonge was something they’d vowed never to do. But of course they did. And of course Forlonge found more speed. He also missed a few speed limit signs on the central coast, where the panel van was used as a roadblock and pacemaker. It was extremely risky behaviour, but when Forlonge rolled up to the Opera House steps less than 10 days after departure, the record was his. Surely it couldn’t get any faster or become any sillier.

It could. In 1978, Terry ‘Tex’ O’Grady, a submariner based at HMAS Platypus on Sydney Harbour, lapped the island on a Honda CB750 F2 and shaved more than a full day off the record. O’Grady also took a support vehicle – a pair of mates in a Chrysler panel van. With the tail lights extinguished the van was used to run interference against wildlife at night, the theory being that the flash of brake lights would alert a closely following O’Grady to danger ahead. Despite this he had a number of high-speed encounters with Mr Skippy. O’Grady did the entire ride on microsleeps, the crew laying him out on the Valiant’s warm bonnet for 20 minutes, then waking him up to tell him he’d been asleep for two hours. By the time he reached the Nullarbor it seems O’Grady would believe anything.

It was a pair of Victoria’s finest who next took on the challenge. Kawasaki had just released the Z1300, which Patrolmen Brian Armstrong and Gary Clapham considered ideal for the task. However, oil and electrical problems plagued Armstrong from the moment they rolled north out of Melbourne. And a tropical downpour reduced speeds to 50km/h between Townsville and Cairns. Clapham was the first to run out of rubber and had to take it slowly into Darwin to fit a replacement. Later, out of fuel and out of hours, they were saved by the local wallopers in Derby who siphoned some fuel from the patrol car. Then Clapham suffered suspected snakebite and worse, a dusted motor and eventual transfer to the support van. Armstrong’s oil consumption problems were resolved only by fitting hotter plugs and a great deal of hope. Suffering severe hallucinations, Armstrong finally returned to Victoria and the security of an escort of police motorcyclists. Clapham jumped on as pillion to enjoy the final victory parade.

To those enthusiasts keeping score it was apparent that, like the four-minute mile, the eight-day mark was there to be broken. And BMW stalwart Ray Kerr-Lansom had the answer. With Kerr-Lansom aboard a new BMW R100RT and Ray Ward on an R100S the pair headed north from Sutherland with morning commuters urged to give them right of way by 2MMM’s Doug Mulray. Twenty-four hours and over 2000km later Ward fell asleep and sideswiped a passing car, then Kerr-Lansom crashed. Later still, both had brushes with stray cattle on the Barkly Tableland, but the first real hiccup occurred on their return to Katherine in the early hours of the morning to find the servo closed. Possibly the local walloper thought that these riders were also from the traffic branch for he showed no recalcitrance in getting the local servo owner out of bed for such important customers.

It was on the same rough gravel road that claimed Don Kerr that Ward suffered a rear puncture putting him out of the running. Kerr-Lansom continued, averaging more than 120km/h for over 20 hours before being pulled over by the police – for a blown tail light globe. He finally picked up a long overdue speeding ticket north of Bunbury, WA – at 50km/h over the limit. His final run-in with the law was when crossing the border into Victoria, however, it was only a licence and rego check; and a slap on the wrist for lack of a front licence plate. Back in Sydney the champagne corks popped. Kerr-Lansom had taken the record for BMW.

That Ross Atkin intended to break the law, and continually do so for several days on end, could have been no secret when he commenced his second race against the clock. Scores of Motorcycle Riders Association members were stationed in every city and major centre around the continent, intent on escorting Atkin through the ‘built up’ areas. In addition, designated service stations along the route were ready to provide Atkin with a speedy pit stop. And, in case anyone missed the point when the huge Z1300 rolled out of the shed, the two large spotlights mounted to the fairing hinted that this was no ordinary Kawasaki. Twin 20-litre pannier containers emblazoned MRA ROUND AUSTRALIA RECORD ATTEMPT provided the final clue for the dimwitted.

Atkin headed north from Melbourne City Square at 2am on an icy spring morning in 1982. Nine hours later he’d passed through Sydney having had to replace the Kawasaki’s fuel pump, a problem which plagued him the entire journey. In Brisbane a new rear tyre, another fuel pump, four hours sleep and he was headed north. Two more fuel pumps, another refuel and he turned west from Cairns. Atkin hit the dirt with the sun behind him, replaced the air filter in Normanton and turned south to Mount Isa where, faced with a good straight development road and clear vision he put on some pace, averaging over 160km/h for four hours straight. This was followed by an equally quick 1000km run up the Stuart Highway to Darwin, and his first shut-eye since Brisbane.

Leaving Darwin before dawn, Atkin faced his fourth day in the saddle with only nine hours sleep since Melbourne. Nevertheless, he was refuelling at Halls Creek by early afternoon and contemplating the dirt track ahead. He made it to Willare only to find that, despite all his planning, the servo was out of fuel due to a petrol strike. After an 1800km day, all he could do was catch an uncomfortable six hours’ ‘rest’ in the roadside ditch while the manager of the servo scrounged enough fuel to see him on his way. It’s over 2500km from Willare Bridge to Perth, but despite being pulled over twice for speeding, and having to hit the chemist in Roebourne for a pick-me-up, Atkin rode into the capital with an average speed of over 115km/h. He only scored the one speeding fine, however, the police now had his number and threatened that if he was pulled over again, he would be detained indefinitely. Atkin hit the mattress in Perth while the Kawasaki was given an oil change, new plugs and a new rear tyre.

5. Rich Willey (left) and Gary Van Straten – perpetual around Australia record holders

Five hours sleep and the knowledge he was on the final legs gave Atkin a new lease of life. He left Perth at 8am and, looping through Albany and Esperance, reached Norseman by dark, his average speed over 120km/h. Forced to take a short kip at Madura roadhouse he knew he was on target. Holding the big beast straight across the Nullarbor wasn’t easy with only the hallucinations for entertainment. By comparison, averaging over 100km/h between Adelaide and Melbourne, one eye out for ’roos the other scoping for patrol cars, and both arms avoiding the Great Ocean Road Armco, the wind chill must have been horrendous. The media were there in force when Atkin rolled in to City Square less than seven days after leaving.

The madness was only hibernating until Gary Van Straten, a Sydney motorcycle workshop manager, calculated the new Honda VF1000 FN carrying 63 litres of fuel was good for 1000km on a tank, and this convinced Highway Patrol officer Geoff Lord that the record could be broken. But before the pair reached Hornsby, Lord struck a large chunk of retread, breaking his foot. Despite the injury, before the day was out they were in Cairns, having averaged 121.65km/h. Lord, however, was unable to continue, leaving Van Straten to press on alone.

Two years later Van Straten was back, this time with Rich Willey, the 55-year-old American hoping his third attempt would prove as successful as his previous two forays. Supported by Gus Liu, Australia’s leading Kawasaki dealer, the pair elected to ride GTR1000 models with custom panniers increasing the fuel load to 65 litres, and fuel pumps from Suzuki wetbikes. Gus described the bikes as flying bombs.

Not since Willey’s ride back in 1974 had a pair of riders survived intact, and the mutual support was of great benefit for a task that’s thirty per cent physical and seventy per cent psychological. Quite remarkable also was the fact that Willey and Van Straten each covered the entire 15,508km on a single set of (then) new Michelin M66 Hi Tour tyres controlled by some special SBS brake pads. Fifteen years after Frank Wheeler first stirred the pot, further attempts ceased.

It would be all too easy to say that the introduction of speed cameras in 1989 foiled any further attempts at the record. But the possibility of broadsiding an 1100kg Brahman bull while sitting on the double ton across the Barkly Tableland was always a greater deterrent than a bankrupting speeding fine. The fact is that largely due to the riots over Easter at Mount Panorama, motorcycles and their riders were on the nose. No manufacturer or distributor wanted to be associated in any way with some hoon blasting along a public thoroughfare. Thankfully the insanity ended before a tragedy occurred.

No limit? No way!

Riders often recall ‘the good old days’ when there were no restrictions on speed outside built-up areas; once the street lights ended you could go full gas with impunity. Unless the person telling you this lived their entire life in the Northern Territory, they’re mistaken. In all other states the sign you see above designated a prima facie speed limit of 80km/h, or mph, if you remember pot-holed roads that were unsafe at any speed.

Certainly it’s true that this limit was only enforced if the police could catch the offender and demonstrate they were travelling at an ‘imprudent’ or ‘unreasonable’ velocity, speed that could be deemed ‘excessive’ or ‘dangerous’. Now these were such subjective terms that any suburban lawyer could dissemble at ease. The cops never bothered, as there were far easier pickings just around the corner from the local pub. All week long.

As far as the Round Australia record holders are concerned, every one – from Barry Renton onwards – must have broken the law every single day of their travels. Then again who’s to argue that riding almost 2700km from Sydney to Darwin in 24 hours is imprudent?

Just how far is it?

When Australian National Route One was announced in 1955, more than half its entire length was more notional than national, with only rough irregularly maintained gravel roads connecting east to west.

In fact, when Americans Rich Willey and Don Kerr informed us in 1974 that the length of ‘Highway One’ was 16,653kms, no one had any better idea. And it was Rich Willey again in 1987 who declared that the length of ‘Highway One’ had been reduced to 15,508kms.

Over those years the highway had bypassed such substantial settlements as Derby, Broome and Wyndham in the west plus Wollongong and Port Macquarie in the east. And since then the four lane expressway has now been built around large regional centres such as Ballina and Kempsey. The length of National Route One now is about 14,400km. And that includes the dirt track through Hells Gate.

STORY PETER WHITAKER

PHOTOGRAPHY CROCODILE PRESS & AMCN ARCHIVES