Kenneth Leroy Roberts was born on 31 December 1951 in the town of Modesto, California. His mother Alice and his father Buster moved Kenny and his step-brother and sister to a small farm on the outskirts of town. And as hindsight would eventually reveal some three decades later, the move was the making of a three-time world champion. And when Kenny’s mum and dad were too busy to ferry his older stepbrother Rick to and from summer school and so bought him a Honda Dream to get himself there and back, title did they know they cemented his enormously successful future.

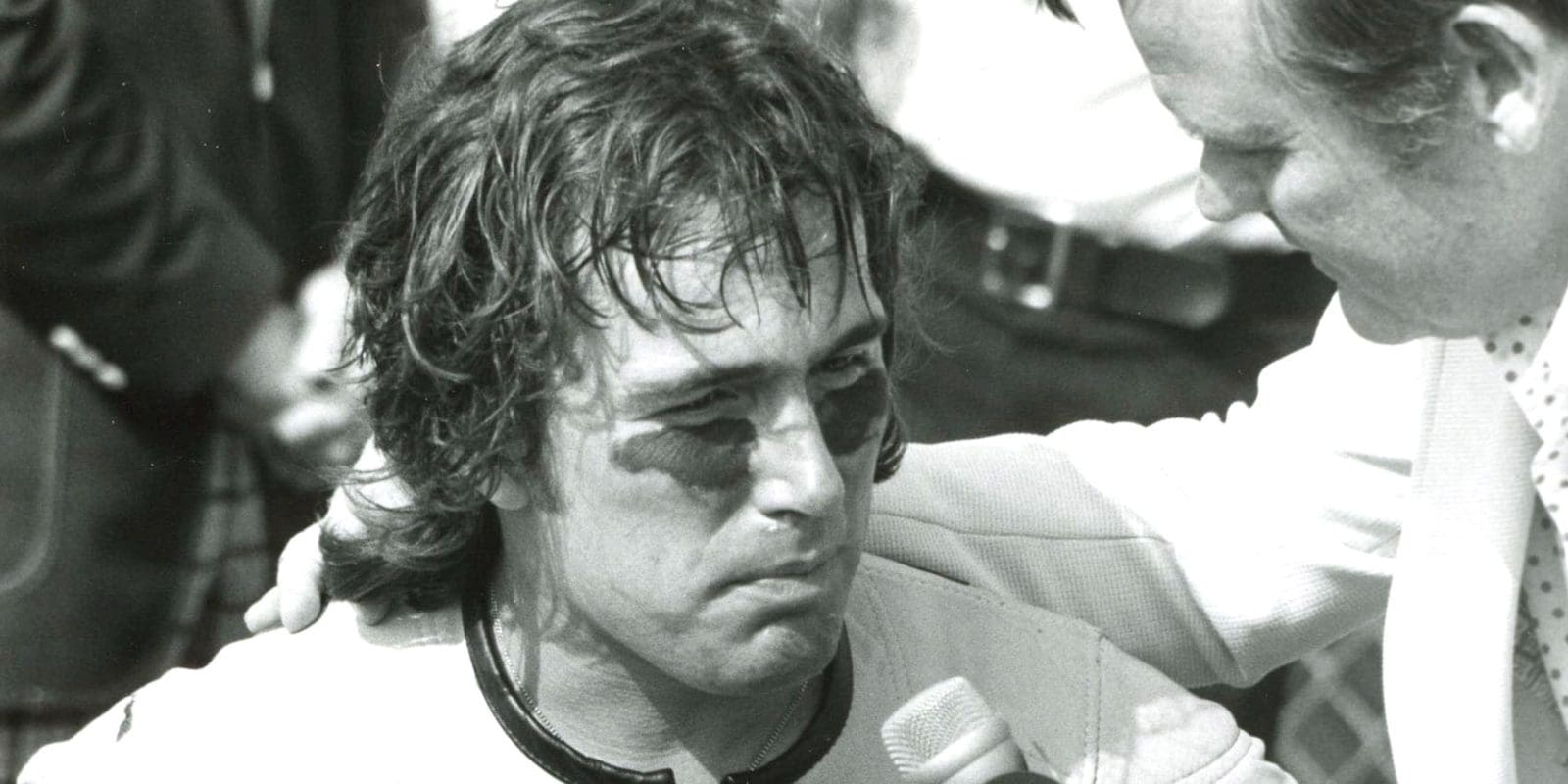

Roberts, #127, starred as an AMA rookie

Roberts, #127, starred as an AMA rookie

Because every afternoon when Rick arrived home from school, Kenny would commandeer the 49cc machine and disappear for hours. A fire was lit inside of him that would never be extinguished. It was around this time Kenny recalls being taken to a local dirt-track race in his hometown of Modesto.

“I saw them going around and around and I thought, ‘Hell, I can beat them guys’,” he says, revealing he came straight home from that race and announced to his parents that he wanted to go racing.

Eventually realising they were never going to change the determined young man’s mind, they bought him his own motorcycle, a Tohatsu. It was a fun bike to ride around the house like he would on

Rick’s Dream, but as a competitive racebike it fell hopelessly short. Kenny persisted with his racing ambitions and so his father replaced the Tohatsu with a Hodaka, the bike of choice for a lot of off-road racers at the time, and took his son racing.

He was immediately fast, beating older and more experienced racers on superior machinery and it didn’t take long before he started notching up the race wins. Kenny’s results were being noticed. The local Suzuki dealer Bud Aksland offered to sponsor Kenny for the 1968 season with a 90cc Suzuki, which soon became a 250cc.

It was also the beginning of lifelong friendship between Kenny and Bud and it eventually led to a 17-year-old Kenny Roberts quitting school to concentrate on his racing. His parents supported his decision, it was clear to them that racing motorcycles really was Kenny’s calling. And when he turned 18 the following year, he was finally able to register as a professional rider with the American Motorcycle Association.

Kenny had been looking forward to that day for a long time. Not least because he could compete in the bigger and more professional races and collect start, finishing and prize money. Kenny lined up in his first race as a professional the day after his 18th birthday. It was a short track race in the famous Cow Palace indoor arena near San Francisco, finishing fourth on debut and pocketing $175 in the process.

“I had never seen so much money,” he laughs.

The results kept coming as he continued to finish ahead of far more experienced and hardened professionals around him. Incredible, really, given how difficult and and heavily contested American Dirt Track races were, and still are. And only the country’s best riders would evolve to compete in the Grand National Championship, where riders had to compete in four different disciplines of racing; TT steeplechase, short and long track racing, as well as road racing.

And while there was always at least one rider who really excelled in one particular discipline, being able to master all three required versatility and talent in equal measure, and being able to dance the fragile line between traction and sliding.

When there was no room, he made some

When there was no room, he made some

As an 18-year-old, Kenny Roberts was outspoken and had a tough attitude but was also very eager to learn. Competing against experienced riders being as young and as talented as he was, rough and sometimes foul play towards him was not uncommon. And while his clean-cut look didn’t resemble some of the other powerhouse GNC riders, he held his own and let his racing do the talking. It quickly became apparent that most riders couldn’t come close to matching him.

“I always thought about what had gone wrong [if I’d crashed]. Most of the time you were run off the track by someone else, often the locals who wouldn’t tolerate strangers on their tracks. They always had to have me. They came after me. That’s why I just tried and fought to stay ahead of them.”

He was quick to challenge America’s very best road racers, like Gary Nixon, #9

He was quick to challenge America’s very best road racers, like Gary Nixon, #9

He formed a close friendships with some of the riders, several of which would go on to become true racing legends. They travelled to races together, the bikes crammed into old, beaten-up delivery vans, often driving through the night to get to race meetings on time. Sometimes they slept between the bikes in the most impossible of body positions.

“That’s why we always took a bag of painkillers with us,” remembers Roberts. “Then it no longer matters how uncomfortable your sleeping position is. The only problem was that we had to take them with water – you don’t want to be continuously stopping on such a long drive because someone has to go to the bathroom again.”

Coming home was another story. More often than not, there was someone with concussion or some other injury.

“We pretty much went straight through to a doctor when we got home,” he continues. “We always made sure to keep someone awake who had suffered a major concussion. No one complained or even mentioned broken or bruised ribs – that was just part of the game.”

Bud Aksland began to realise he could not really help Roberts much more than what he’d done. He knew that if he wanted to rise above the Californian dirt-track scene, he would need more professional help from people who could also help him with his road-racing career, which at the time was Roberts’ weakest link in his Grand National campaign.

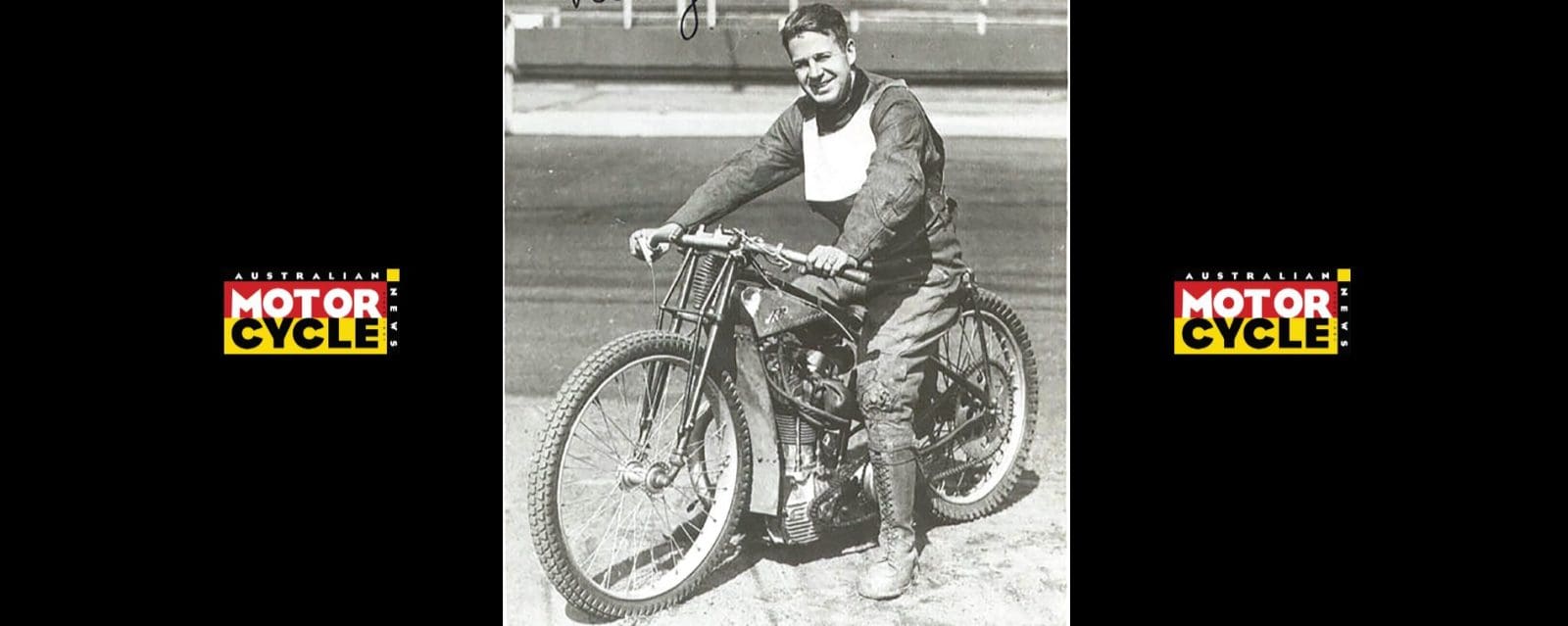

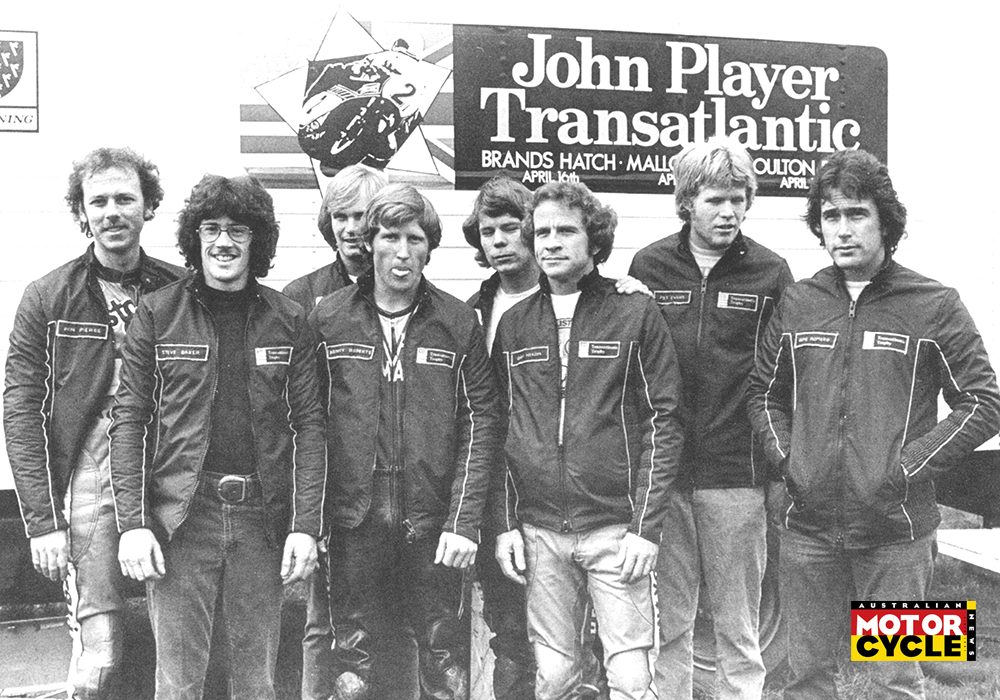

Team USA, 1976 Transatlantic series, L to R: Ron Pierce, Steve Baker, Randy Cleek, Kenny Roberts, Pat Hennen, Gary Nixon, Pat Evans and Gene Romero

Team USA, 1976 Transatlantic series, L to R: Ron Pierce, Steve Baker, Randy Cleek, Kenny Roberts, Pat Hennen, Gary Nixon, Pat Evans and Gene Romero

Aksland introduced him to Jim Doyle, who became Kenny’s personal manager. In 1971, Doyle decided to approached the American Triumph importer for sponsorship. Triumph turned him down, saying Kenny Roberts was too small to become successful. So they tried their luck at Yamaha instead where the director of Yamaha USA, Terry Tierman, signed a 19-year-old Kenny Roberts as a factory Yamaha rider.

With factory bikes at his disposal and wage big enough to pay himself and a mechanic, Roberts hired Aksland to prep his machinery. It also made it possible for him to compete in all Grand National disciplines. Until that point, he’d only ridden in a handful of the road races. But that was about to change.

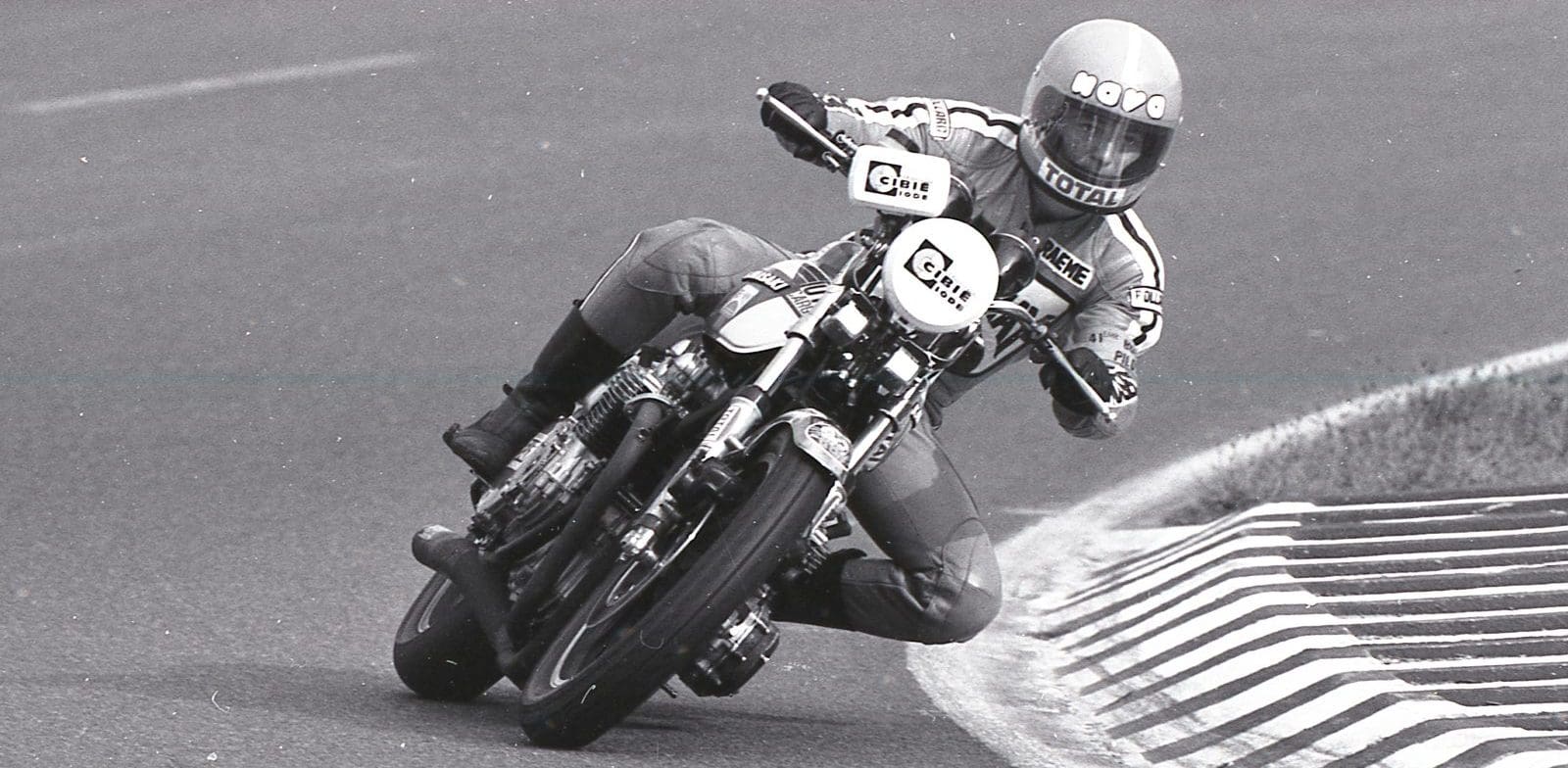

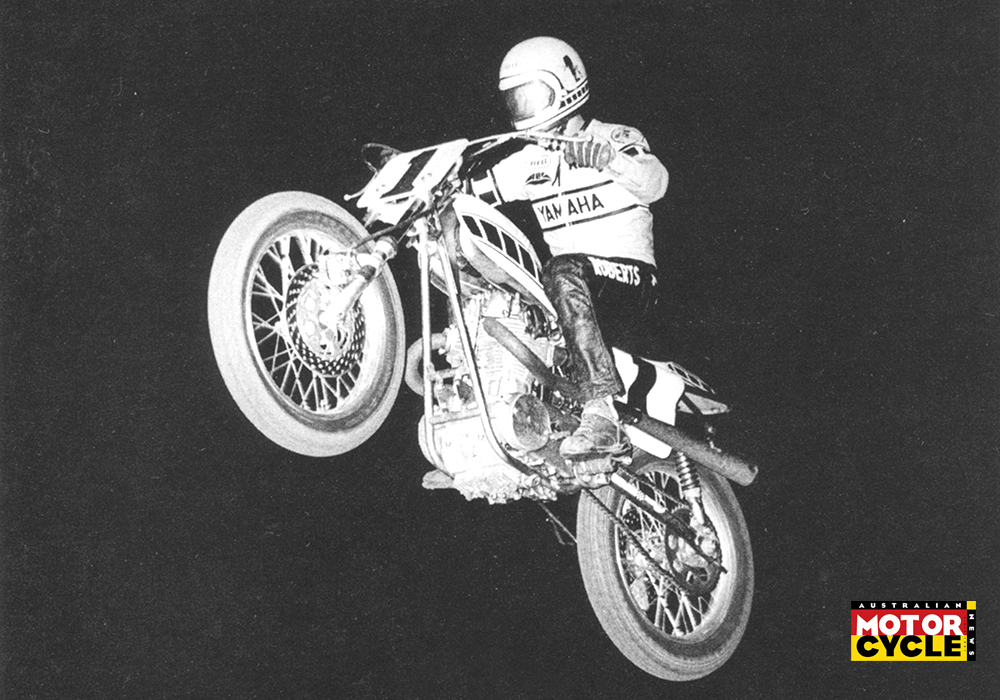

In 1978 Roberts also raced in 250 GPs

In 1978 Roberts also raced in 250 GPs

Lining up alongside Yamaha teammate and 1969 250cc world champion Australian Kel Carruthers, the flag dropped and Roberts led the 350cc race from the start with Carruthers in hot pursuit. Halfway through the race, Carruthers passed the young American. Roberts could keep up with him but not overtake him, though an ignition problem shortly after forced him out of the race.

Kenny Roberts’ skills off-road were well known, but it came as a surprise many that he was so strong in road races which such little experience. Carruthers recognised Roberts’ talent and took him under his wing. His workshop became Roberts’ and Aksland’s the new base, as the Aussie became his mentor, both on the track and off it. It was the beginning of what would become a long working relationship between the two, one that intensified even further in 1973 when Carruthers called time on his racing career and became manager of Yamaha’s racing team in the US.

Kenny Roberts won AMA’s Rookie of the Year Award in 1972 and won his first Grand National race the following January at the short-track event held at the Astrodome in Houston, Texas. But it didn’t come easy, his Yamaha dirt tracker was powered by a heavily modified XS650 engine. He was up against an arsenal of factory Harley-Davidsons and his parallel twin had a difficult time against the heavily tuned V-twins the vast majority of riders used. These machines had been developed, built and modified very specifically fo this style of racing, and the Yamaha delivered much less power.

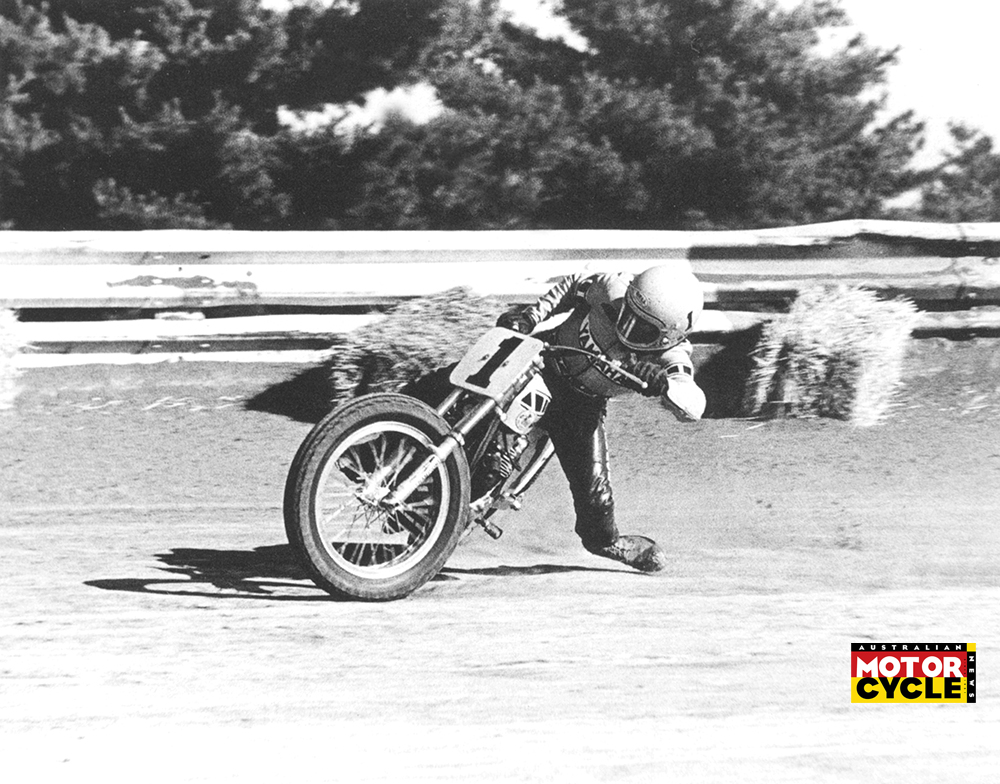

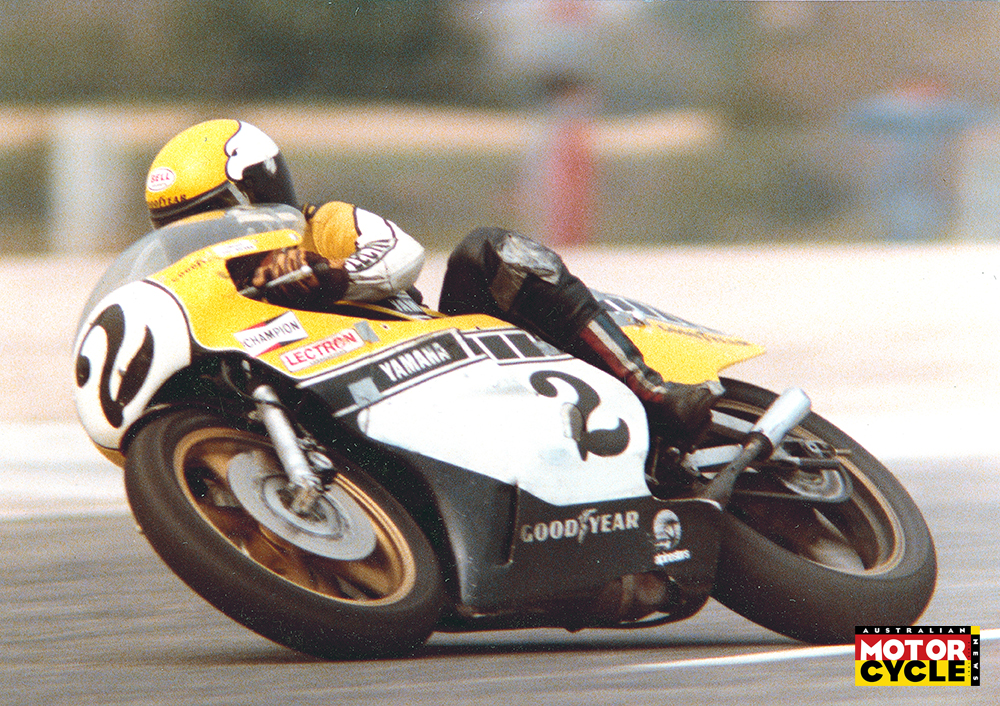

Roberts won the 500 title at his first attempt

Roberts won the 500 title at his first attempt

But what the engine lacked in output, Roberts made up for with ability and determination. And he used that same ability and determination to become the 1973 Grand National Champion in just his second attempt, and at just 21 years of age, also becoming the youngest rider ever to loft the coveted title trophy. He still remains just one of four motorcycle racers in AMA history to take the coveted AMA Grand Slam, with wins in all four of the Grand National genres.

“At the time, the dirt trackers that were riding at tracks like Ascot Park, Louisville and Springfield were seen as real daredevils,” explains Kenny. “The riders who did road races on hard surfaces were seen as cream puffs. But I noticed that this was slowly changing during the period that I started riding asphalt. You know, our two-strokes in the mid-1970s could cover three miles in one minute at Daytona, speeds of 180 miles per hour (288km/h).”

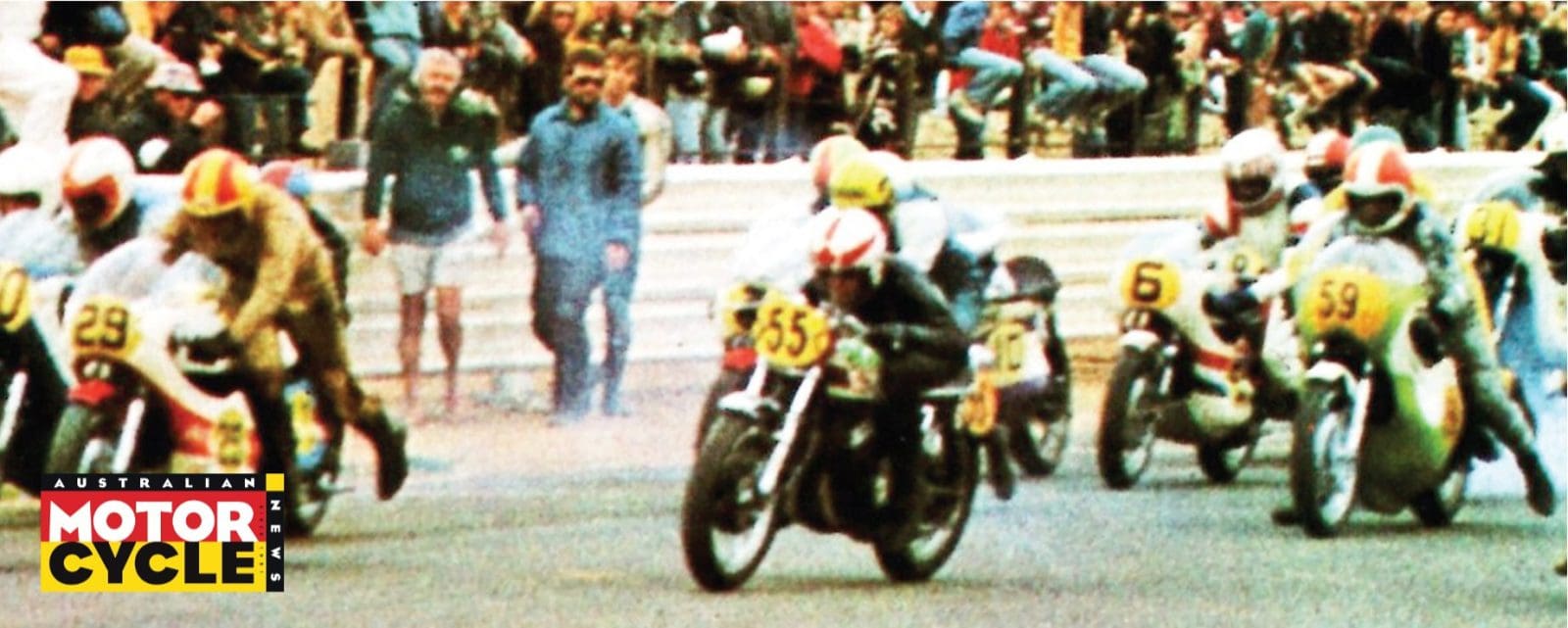

USA vs The Poms at Brands Hatch in 1976. Roberts challenges Barry Sheene, #7, while Pat Hennen, #40, Mick Grant, #4 and Barry Ditchburn, #5

USA vs The Poms at Brands Hatch in 1976. Roberts challenges Barry Sheene, #7, while Pat Hennen, #40, Mick Grant, #4 and Barry Ditchburn, #5

Despite the tough transition, Kenny Roberts didn’t take long to get used to riding the fast but temperamental two-stroke racers. He slowly but surely perfected the drifting riding style he mastered on the dirt and how successful that style could be on the tarmac became apparent in 1974.

After his second-place finish in the Daytona 200 which he scored on his way to successfully defending his Grand National title, Kenny Roberts made his first visit to Europe. There he finished second in the Imola 200 before competing in the Transatlantic Trophy races in England, a competition between American and English riders, and stunned his competitors by winning three of the six races and finishing second in the others. He won the series ahead of runner up Barry Sheene, who was the reigning Formula 750 world champion at the time.

Roberts vs Cecotto in the F750s

Roberts vs Cecotto in the F750s

The world was warned, especially when Carruthers took Roberts to Assen to participate in the Dutch TT the same year. making his GP debut in the 250cc category, Kenny Roberts left an indelible impression after he topped practice and set a new lap record on his way to finishing his first-ever grand prix on the podium in third place. He loved the experience, but Roberts had no aspirations to be regular participant in GPs, preferring to remain in America where he could compete in both dirt track and road racing events.

In 1974 Roberts, Carruthers and Aksland experimented a lot with different engines and different frames, looking for the golden combination to beat the Harley XR750s which had the upper hand. Using that same ability and determination, he managed to win enough races to take the title, but the 1975 season made it clear Yamaha needed to make some serious changes. The Yamaha could no longer compete with the ever-improving Harleys and it was during the Indy Mile in August of that year, Yamaha made a last-ditch attempt to boost their star rider’s points tally.

It was out with the twin-cylinder four stroke and in with the four-cylinder TZ750 two-stroke that powered his Formula 750 road racer. Mounted in a lightweight frame, the high-revving powerhouse was completely unsuitable for a dirt track application, but Roberts was so fed up with the domination of the Harleys, he was prepared to give anything a go.

“I didn’t race the track and I didn’t race the other riders,” laughs Kenny. “I was really just trying to keep the bike on the track. At one point I thought that I might as well steer the bike to the outside of the corners and open the throttle. I thought if things go wrong I am close to the strawbales so a crash would be short and reasonably painless.”

KR also took on the best in the 750s when he went to Europe

KR also took on the best in the 750s when he went to Europe

Despite the hellish handling of the bucking Yamaha, he did manage to keep it on track. He was midfield with two corners to go when that determination took over and he rounded up every rider ahead of him before the chequered flag to take the win. None were more surprised than the leading duo of Corky Keener and Jay Springsteen, Roberts’ two biggest championship rivals.

“I had absolutely no idea what happened when Kenny with his howling and bouncing two-stroke came full-on from the outside,” recalls Keener. “The way he did it was really terrifying and somehow he managed to keep that thing on track too!”

The 1980s brought a new look

The 1980s brought a new look

Seeing the potential, a few other teams also tried their luck with a 750cc two-stroke engine, resulting in some nasty accidents. The AMA responded swiftly prohibited further participation of what some were calling the grand prix dirt-trackers. As a result, Roberts couldn’t compete against the overwhelming domination of Milwaukee’s XR750. He finished runner-up in 1975, third in 1976 and by 1977 he didn’t win a single dirt-track race.

Road racing, however, was a different story. He celebrated victory in five of the six Grand National road-racing events, he won six of the seven races to claim the American Formula One Championship, cleaned up again in the Transatlantic Trophy races and broke the lap record on his way to winning the Imola 200. But his fourth place in that year’s Grand National ranking forced Yamaha USA to make a decision that would lead to an important turning point in Kenny Roberts’ career.

The King’s legacy was a wave of American GP racers like Freddie Spencer, Randy Mamola and Eddie Lawson

The King’s legacy was a wave of American GP racers like Freddie Spencer, Randy Mamola and Eddie Lawson

The dominance of Harley, the large expense of racebikes and the now very high salary of their rider were no longer compatible. In consultation with Yamaha Japan, the factory decided Roberts would compete in the 1978 grand prix racing season, campaigning in the Formula 750, 250cc and 500cc World Championships with Kel Carruthers at the helm.

Roberts didn’t want to go. He loved America, its familiar culture and wanted to stay put. So Yamaha took America to Europe. Wherever possible, Yamaha would fly Kenny’s wife Patty and two kids Kenny Jr and Kurtis to races and, while other riders where working out of and sleeping in tents, Yamaha shipped a luxurious motorhome to Europe for Kenny to stay in, complete with American food and drinks, even American music playing through the speakers.

Roberts takes on Sheene and Wil Hartog

Roberts takes on Sheene and Wil Hartog

Given his inexperience on European circuits and that he had three classes to concentrate on, two-time 500cc world champ Barry Sheene said he didn’t deem Roberts a threat. But that quickly changed when results came. And with two very big and different personalities, the pair became great and bitter rivals, as Yamaha mechanic Nobby Clark remembers.

“When Kenny joined the team, it quickly became clear to us that he was a truly great rider. He knew exactly what changes he wanted on a bike, he never complained but gave solutions instead.

“Sheene, in particular had a hard time dealing with him. He told everyone that Kenny was so good because of his Goodyear tyres. Funny thing was that Pat Hennen sometimes finished second behind Kenny and he rode with the same tyres as Sheene. Barry was a good rider, but Kenny was better.”

California vs Cockney was racing’s biggest drawcard in the 1970s; Roberts and Sheene

California vs Cockney was racing’s biggest drawcard in the 1970s; Roberts and Sheene

When Kenny remembers Sheene that year, that outspoken trait returns.

“Barry knew very well how to play the press and the fans, he won most races in the press, I [won them] on the track. I didn’t have time for these games. I had to get to know all the circuits, find the right set-up for my 250, 500 and 750 racers and I was very busy testing tyres for Goodyear as it was their first year in Grand Prix. A really tough year.”

But a very special year, too, because in his rookie season he became the first American to win the 500cc world championship. He finished fourth in the 250cc world championship, second in the Formula 750 title and won the prestigious Daytona 200.

He was second in France in 1978, behind Gregg Hansford

He was second in France in 1978, behind Gregg Hansford

How does Kenny view that landmark season?

“I don’t know, for me it’s all about winning, regardless of the challenge,” he says. “My focus was always on riding a motorcycle better than anyone else. I didn’t care what the problems were in what season. There is always something going on and I was still very determined to do better than anyone else. I was very driven by that. That is also how I want to be remembered, as someone who gets on a bike and really goes for it. No matter the conditions, no matter the bike, no matter the circumstances.”

And that’s exactly what he always did. From the first time he rode off on Rick’s Honda Dream to his very last race at the 1983 San Marino 500cc Grand Prix, which he won from pole position.

Words Ivar de Gier

Photography Archives A. Herl