Kawasaki has draped the letter ‘Z’ on bikes since the Z1 in 1972, an era when one bike had to do it all: tour, scratch, race, commute, rally and more. Those early Z bikes did ‘engine’ very well, and ‘bullet-proof’ pretty well too. Handling, not so much. But no one cared about handling back then – it was all about tuning them to a standstill and vision-blurring grunt. Kawasaki Z bikes did that well.

These days, bikes have gone into niche mode, with a different model for each purpose. There’s a growing number of riders utterly oblivious to bikes sitting outside their perceived domain – a cruiser for cruising, an adventure bike for going off road, a tourer for touring, etc. The only two-wheeled genre that remains ‘do it all’, mostly anyway, is the nakedbike. With this in mind, Kawasaki has produced a bargain bike that will be many things to many people: the 2017 Z900.

While the years have separated this model from the original Z1 in tech and looks, the mainstream-appeal concept remains similar, and some serious effort has gone into this machine to broaden its capabilities. The evolution of technology and tyres has meant bikes like this can now exist at a price many Aussies can afford, even if it means saving up or buying into a finance program.

Kawasaki isn’t the only offering in this market. The Yamaha MT-09 (see Vol 66 No 19) is around $200 less and also a 900, albeit it a triple and part of the MT family. There is choice out there – so why would you choose the Z900? Well, there are plenty of plusses and only a few minuses.

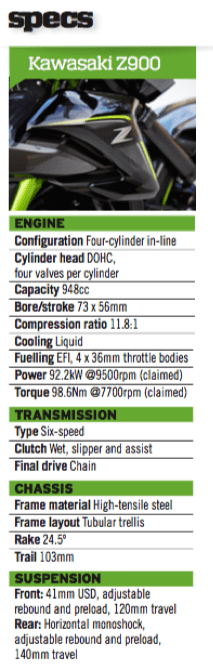

Engine output is similar to a mid-90s 750 superbike, but much easier in delivery, with no need to punch the roof out of the tacho looking for power. This is where the tech comes in – ignition and fuel injection improvements mean this bike is so easy to ride. So easy, in fact, that Kawasaki left traction control off it altogether.

This is clearly a cost saving measure, given most of Kawasaki’s big-bore offerings feature some form of TC and position it as a crucial rider aid, but it’s also a measure of how Kawasaki rates the rideability of its supernaked. There’s a natural connection to throttle feel and rear wheel grip and I never once craved TC during my three-week stint on the bike.

Perhaps most telling is the fact one of the bike’s fiercest competitors, the MT-09, features switchable TC. If Kawasaki thought it was genuinely a major selling point, it would have made it work on the Z900 somehow.

The dash features shift-up lights, but they are superfluous – the bike will shift sweetly in the midrange, as you torque the bike between corners. It’s quieter this way, too. For those who don’t want quiet, Kawasaki claims to have engineered a pleasing induction roar. Whether by design or not, the bike does hum when you crank the throttle wide open and the result is satisfying scenery blur.

The bike is also equipped with a slipper clutch via its span-adjustable clutch lever, though I found the ability to manually match revs on the downshift so precise, I didn’t trouble it much. It is a handy feature when pushing on, however, and certainly something to bring up in the pub as you trade feature-for-feature blows with your riding mates.

Despite their obvious differences, the in-line four of the Z900 feels very similar to Yamaha’s triple. If anything it’s actually easier to modulate throttle openings and feels slightly superior power-wise up top.

They are similar because they are smooth, easy to use and so incredibly broad. Kawasaki has done a great job matching the triple’s abilities off the bottom here, yet retained a four-cylinder feel.

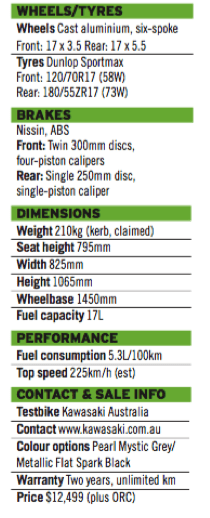

Kawasaki has also done well making a 900cc four feel so bloody small! The seat height has a lot to do with that – at a claimed 795mm, your derriere is not far off the deck. This puts you deep behind the tank and instruments and makes for an upright ride position, more than most nakeds already offer. While it’s is a comforting position to be in for smaller riders, the downside is leg room: anyone over 172cm or so will feel cramped. If I owned one, I’d be looking for a taller seat, to not only give me back some leg room, but also to pivot my weight over the front end more.

The bike feeling so tiny means it’s a joy lofting it from side to side in corners and it feels even lighter than the claimed 210kg wet weight. This is where that lairy – and lightweight – green trellis frame comes into effect.

The bike handles better than you’d expect from a $12,495 (+ ORC) motorcycle, and it does so because it’s balanced. The low centre of gravity, aided by that miniature seat height, and the fact Kawasaki has placed the bike so evenly between the wheels, then added suspension that provides decent feedback, means it can be hustled through twisty backroads in real-world conditions at real-world speeds.

The high-tensile steel frame would probably fade into obscurity had Kawasaki not dipped it in bright green paint – it’s so bright, the frame almost looks too much for the rest of the bike. If anything, I wish Kawasaki had taken the frame’s lead on colouring and gone full-spec lair with a few more components.

That frame is a claimed 13.5kg according to Kawasaki, with the swingarm chiming in at just 3.9kg. This is light, and on the road it translates to a compliant, well-balanced road sled, destined to please a wide range of riders in a variety of conditions.

I’d be happy doing a ride day on this thing, sitting a tankbag and rear rack on for some extended touring duties (with a taller seat!) and even hitting the custom trail to finish what Kawasaki started with that green frame and make it even more ‘streetfighter’.

The front end is obviously related to the Z1000’s rock solid front girders, and while not providing quite the same level of feel and grip, it is amazing bang for front-end buck at this price point.

The nod to the price tag comes in a lack of compression adjustment – there’s preload and rebound adjustment only; however, the front end supported my 86kg admirably in normal road-riding duties.

The rear shock itself may look cheap, but it’s much more progressive than it appears and offers preload and rebound adjustment, too. Both ends are, as mentioned, well balanced, not just in forward/rear weight bias, but with the damping as well.

Altogether, the easy-to-use engine and great feel from the front and rear ends adds up to a bike that doesn’t have me lusting after a traction control system. At all. Technology and tyres can make traction control less of a necessity, and that seems to be the case here.

Where there is rider assistance is at the brake levers. Dual 300mm petal discs clamped by Nissin four-piston calipers is a lot of braking power. I have always enjoyed using Nissin calipers, which aren’t as trendy as Brembos but are excellent for lower cost bikes – good feel and predictability, great power.

On the Z900, they are hooked up to a Nissin ABS system. It isn’t the most sophisticated unit going around, cutting in early and not as smoothly as higher-spec systems, and when hard braking on bumpy surfaces the ABS became mildly annoying. Everywhere else though it is effective, and should I hit a sand patch I didn’t see while braking hard it would be a good addition. The ABS works on both ends and is on permanently.

The gearbox is a gem. The clutch lever is assisted, meaning it’s light and progressive to use, and going north and south through the well-spaced ratios is so easy, I almost forgot to mention it. It’s one of Kawasaki’s best gearboxes, I reckon. I’d just add a tooth or two to the rear sprocket to give acceleration an extra bit of spice if Kawasaki let me keep it.

So dynamically, the Z900 is a joy for the price – it’s $12,495 well spent, performance-wise. But what’s it like to live with?

The dash is a pleasure to look at, not always the case with Kawasaki items. The gear position indicator is handy, because the bike is so torquey it’s easy to forget which gear you are in. There are three display modes to choose from, and you can angle the dash to suit your height easily, by just grabbing and pivoting it.

The carbon-fibre-replica surround is an odd touch, as there isn’t any fake CF anywhere else on the bike, so I suspect it’s there to hide screws and the like. My favourite feature is the range readout, making it easy to push every last kilometre out of the bike before limping into the servo – 250km from a tank is doable.

Ergonomically, cramped legroom aside, the bike is as neutral as it gets. The tank is narrow between the knees, and sitting well forward is a cinch. Rubber-topped footpegs are a nice touch, and the ’bars are a natural width for me – not too narrow and not too wide.

The mirrors are a triumph of style over substance, like many these days, but they do offer vibration-free rearward views when you tuck in the elbows for a meaningful glance. The sidestand passes the ‘awkward’ test – I don’t need to look down to hit the tang and pulling into the servo while extending the sidestand for a classy dismount is entirely possible. Just remember you will look Maximum Goose if you get it wrong.

I really want to say this bargain-priced machine is perfect for riders fresh onto a full licence, given how easy it is to ride and how affordable it is, but that would be selling the Z900 short. It’s a proper nakedbike, even at this price point, and with a taller seat and some extra green bits I’d be happy to live with it.

Keeping Kawasaki’s Z bikes up to grade over the years has been a tough order given the heritage, however, this 2017 Z900 is right on point. Dynamically sound and offering some very enjoyable riding at a bargain price point, it deserves attention from those in the market for a nakedbike they can just buy and ride.

What’s also apparent is that more and more the configuration of an engine is becoming less of a decision-influencing point – this bike feels not dissimilar to the triple-engined 900s it battles in the marketplace, including the XSR ($12,999 + ORC) and MT-09 ($12,299 + ORC).

Give me more green, a taller seat and call it done!

So dynamically, the Z900 is a joy for the price

REPORT SAM MACLACHLAN

PHOTOGRAPHY JOSH EVANS