The big buzz at the moment is Suzuki’s brave decision to relaunch the Katana, its icon model of the Eighties. If Suzuki’s car division can relaunch the Jimny, why shouldn’t it do the same for the Katana.

Both are instantly recognisable to former Seventies longhairs and have a simple kind of honest kudos that appeals to seekers of the simpler things in life.

I remember watching an early-model Jimny pull a bulldozer out of a New Zealand ditch in the early 1980s. It was powered by a two-stroke, three-cylinder, 550cc engine so was relying on the low gearing and strength of its high-low transfer case to do this.

Another time a friend and I had struggled to get a V8 Land-Rover 109 wagon down a steep and dangerous track in Northern Victoria’s gold mining region. Coming up towards us was a little Jimny, doing it easy.

Likewise I have similar memories of Suzuki’s Katana. Watching one being wrestled around Winton in production racing by some guy called Rob Phillis. Seeing another parked up at Mount Hotham village, in the days when most of the road in was gravel.

Ah, the memories come flooding back.

The really interesting thing about the Katana is how Suzuki has revisited it with a similar attitude to the 1981 original. Both use existing engines and chassis with distinctive bodywork.

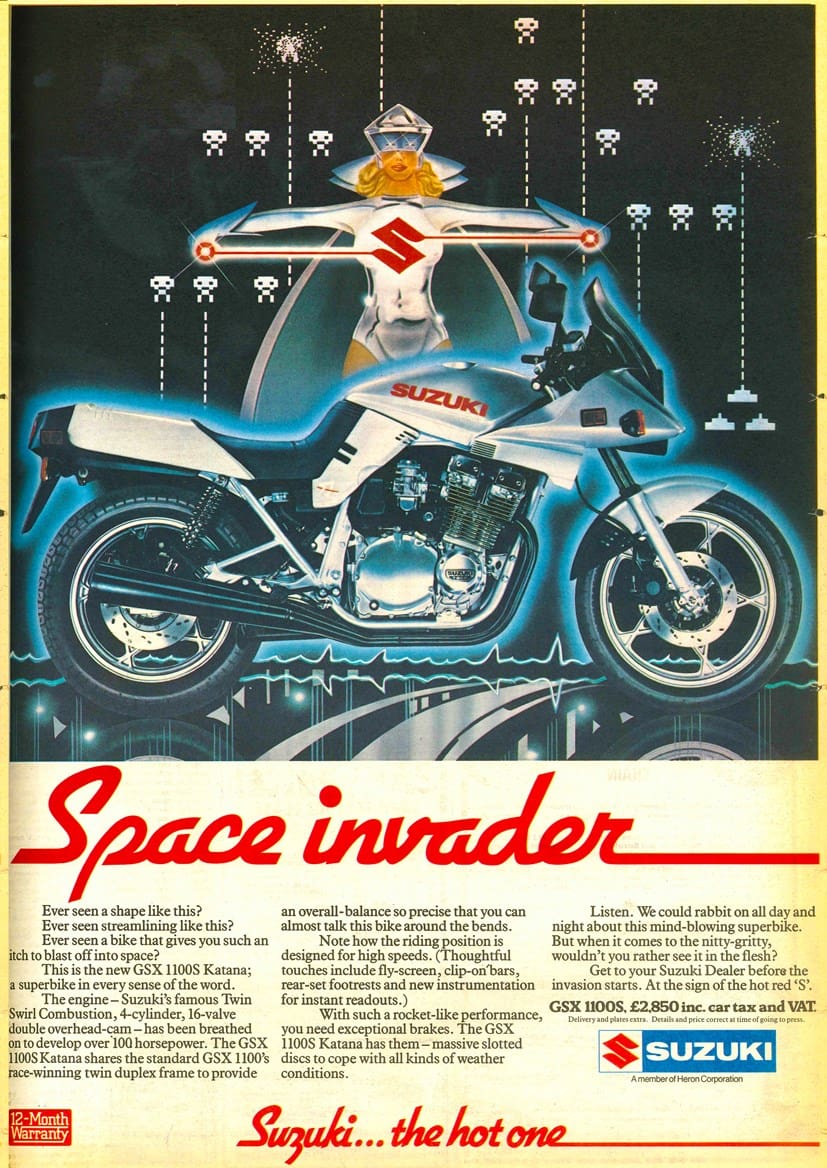

The early-’80s Katana was a GS1100E dressed up in what one commentator of the era described as “Star Wars-theme party clothes”.

Nevertheless the Katana made it into the 1998 Art of the Motorcycle exhibition in New York’s Guggenheim museum. It was the first time motorcycles had been displayed like art forms and was such a success the exhibition went on tour.

The accompanying catalogue said that “even in a flooded motorcycle market, the Katana was an enormous sales success. It continues to give motorcycle designers pause for thought, as its popularity was due entirely to its space-age looks rather than its functionality.”

As the 1980s dawned, Europe’s Target Design was commissioned to freshen up Suzuki’s long-running GS series, now powered by a 1074cc version of the original 750cc air-cooled four cylinder engine.

This sort of styling had been attempted before, most notably by Triumph’s Craig-Vetter-designed X75 Hurricane of 1973, although that was more chopper-inspired than futuristic road racer.

It also was a very limited-edition model, not the sales bonanza the Katana became. Released in Australia in late 1981 in 750 and 1100 versions, the Down Under market got a wire-wheel option.

Why? Because production racing was huge back then and the wire wheels were slightly different from the standard cast items, allowing a wider tyre choice.

By all accounts the handling wasn’t out of this world, but the Star Wars styling was backed up by a hairy-chested engine. Its 82kW made it the most powerful production motorcycle on the market.

Suzuki trumpeted the fact that the Katana had a hydraulic anti-dive system on its front fork. “A new chapter in motorcycle performance,” its publicity brochure claimed, but could this be backed up?

Yes. The Katana’s world racing debut in the hands of Kiwi hotshot Neville Hiscock saw the Amaroo Park 750cc Production Class record smashed.

Hiscock went on to achieve a similar feat on the 1100ccc version at a three-hour race at Surfers Paradise.

The Katana really took off in 1982, campaigned by riders like Rob Phillis, but late that year Honda’s much more sophisticated VF750, water-cooled V4 seized the spotlight on showroom floors.

However, the Katana retained a loyal following and even starred in one of Australia’s most provocative films.

Long before she became Mrs Jackman, Deborra-Lee Furness burst onto Aussie film screens in 1988 in Shame. She played a bike-riding barrister marooned in a misogynistic country town after crashing her Suzuki Katana.

Shame was one of the most powerful Australian movies of the 1980s and last year was digitally restored and screened at the Melbourne International Film Festival.

Meanwhile original Katanas are getting restored all around Australia.

It’s a timeless bike, alright.

By Hamish Cooper