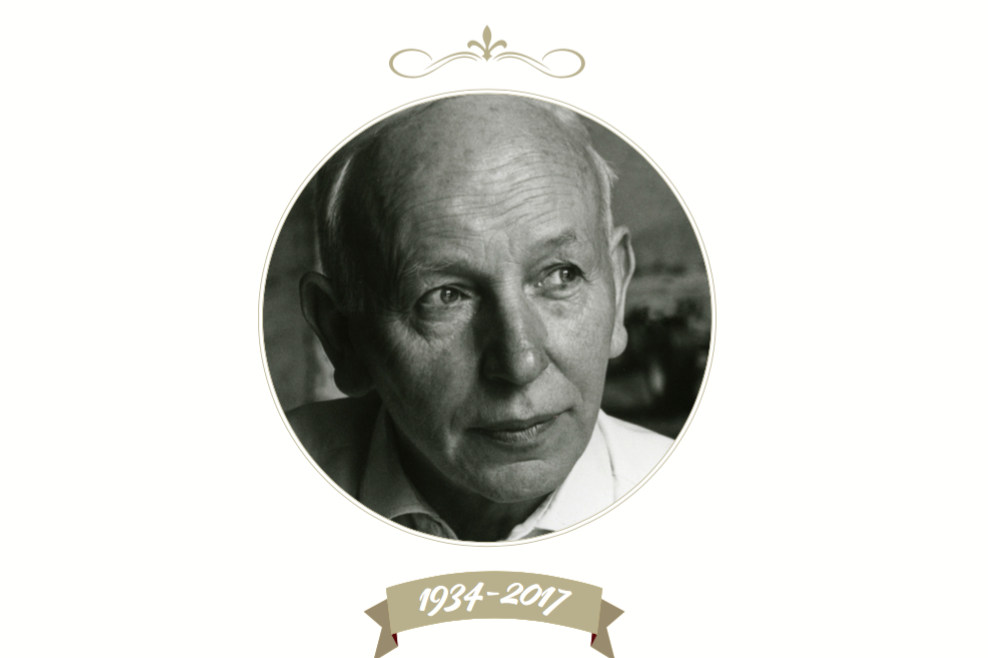

In his autobiography, John Surtees spoke of “the inherent Surtees family cussedness”. He was describing his father. Many people who knew John as a racer would say the same about him. Certainly he was stubborn. John Surtees was also intelligent, far-sighted, mechanically gifted, intensely competitive, and a perfectionist – qualities that mark out the greatest champions in this and other branches of motorsport.

Indeed, this English rider eventually left motorcycling for cars, and four years later won the F1 World Championship in a factory Ferrari. He remains the only man to be world champion on two and four wheels at the premier level and, given the level of specialisation today in both disciplines, is likely to remain so.

After retirement, pondering whether two or four wheels had been more important to him, he plumped for motorcycles, writing in John Surtees – World Champion (Hazleton), he said: “The relationship between a rider and a motorcycle

is … more personal than that between a driver and his car. On balance … I derived more pleasure from my bike racing career than my time with cars’.

It’s a typically painstaking statement that will strike a chord with every motorcyclist, whether or not they were around when this slightly doleful-looking youngster from the southern outskirts of London emerged at speed in the early 1950s to take over from (to an extent even ousting) the debonair Geoff Duke.

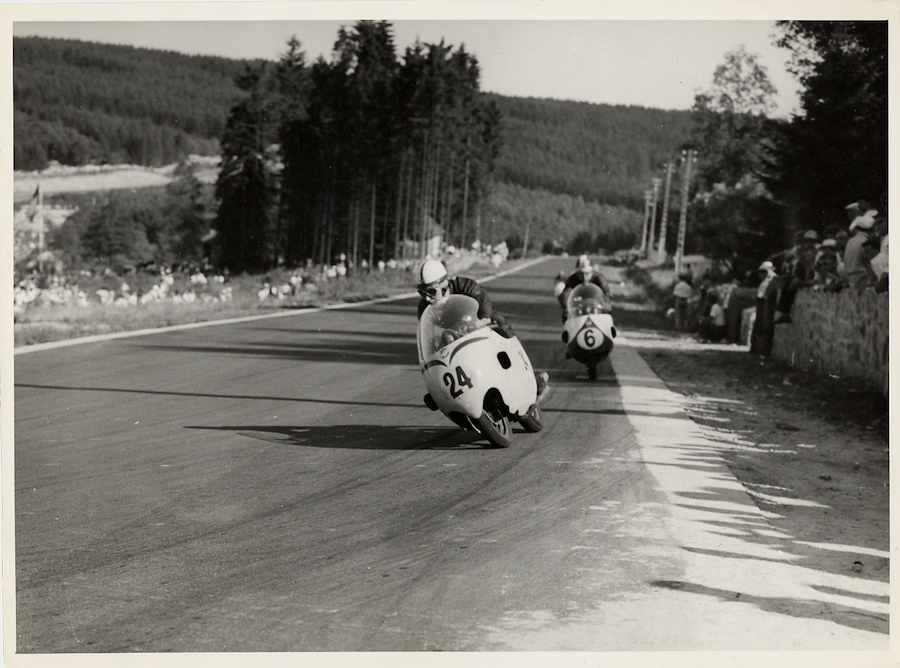

Surtees discovered new lines, new angles of lean and new ways of getting speed out of the unwieldy looking dustbin-faired four-cylinder giants from Italy. Not that John, a cussed Surtees to the core, wouldn’t rather have been on a single-cylinder Norton, if only the English factory had listened to him.

John was the elder of two brothers, born on 11 February 1934 in the small village of Tatsfield, on the Kent-Surrey border. His father, Jack Surtees, was a grass-track sidecar competitor of note and it was at the family’s local grass-track circuit, Brands Hatch, that young John first rode a motorcycle. It was a Wallis-Blackburne speedway bike, and the 13-year-old lad ran round and round the cinder access road outside the track.

A year later he made his competition debut, riding passenger in his father’s sidecar outfit in a speed trial – they won, but were disqualified because John was under age.

At 16 he was old enough to start grass-tracking, riding an Excelsior.

By now Surtees was also gaining hands-on experience in the workshop of his father’s motorcycle shop. As well as basic skills, he learned the art of creative engineering – how to use imagination and technique to get the most out of an existing design or component. One of his early projects as a schoolboy was to fit his bicycle with sprung suspension, all made by hand. Money was tight; hard work and careful preparation took its place.

Surtees was soon racing every weekend, quickly moving from grass-track to tarmac, where he campaigned first a Triumph, which was soon supplemented with a single-cylinder Vincent Grey Flash. But he still regarded himself as “just a mechanic who rode a bike”.

The breakthrough moment – when he became a real racer in his second season – came at Aberdare Park in Wales in 1951. He was 17 years old, and it was his first victory. This was the one he chose when I asked him to nominate his greatest race.

“I don’t really have a greatest race. I don’t look at it like that; in racing, it’s always the next one that’s the most important.

“It’s easier to go along and pick a milestone, and the one turning point that comes to mind is the first race I won. I could also choose my first foreign win, or my first grand prix win. They were all milestones.

“But let’s stick with the first win, in 1951, in a British national meeting at a little park circuit in Wales. Until then, I’d ridden a 250 Triumph and an Excelsior-JAP on grass tracks, and the Triumph a little on road tracks, with the main result that I’d skated up the road on my backside.

“It was there that the confidence was born that is required to be a real competitor, and to win. The bike and I became one. We were exchanging messages through the seat of my pants.”

His stern-faced father had a depth of racing experience and widespread contacts through the industry. He supported John when he joined Vincent as an apprentice, and helped him to buy the Grey Flash from the works, as a box of bits.

Vincent encouraged his racing as he piled up the victories on the British short circuits. In 1953, he won 30 out of 60 races entered, but he also remembered falling off at almost every race in his early days.

Almost from the start he had been up against the hero of the day – six-time world champion and GP racing’s first superstar, Geoff Duke. A press cutting Surtees proudly kept from that time described him as ‘the man who made Duke hurry’. The reigning world champion was to provide a worthy yardstick and target for his fast-rising rival, but there was never any question of modelling himself on the stylish older Englishman. Then, and forever afterwards, Surtees had his own ideas on how things should be done.

This was a time when the Italian factories were on the rise, while Norton was holding firm with its light and slender but relatively archaic Manx single.

In 1953, Duke moved to Gilera, frustrated by Norton’s intractable conservatism. The company was wedded to convention and by now its bikes were thoroughly outpowered by the four-cylinder Italian machines – though they were still able to win races in the right hands.

Seeking a replacement, Norton’s legendary team boss Joe Craig approached Surtees for the Isle of Man TT in 1953. That went wrong when Surtees crashed in practice, riding a 250 EMC two-stroke. But he would be forgiven. After another strong season in 1954 on his own Nortons he was taken into the factory team in 1955 for ‘major events’, including a handful of championship rounds.

Surtees was particularly fond of his victory over Duke’s four-cylinder Gilera in a late-season international at Silverstone in 1955, avenging an earlier defeat at Aintree. This was followed by another win at Brands Hatch.

Fulfilling his creed of racing whenever possible, and reflecting his growing stature, Surtees had a trial outing on a fuel-injected factory BMW and had also campaigned his own 250 NSU, on which he won the Ulster GP, his first world championship victory. He finished almost half a minute ahead of Sammy Miller on a similar bike, with double 500cc champion Umberto Masetti third on an MV Agusta.

While 1955 had been a year of portent, in 1956 the omens came true.

Surtees had several options, with tentative approaches from Moto Guzzi and Gilera, interest from BMW – although the German factory’s plans were indecisive – and a firm offer from MV Agusta to partner Masetti. Most of all he wanted to stay with Norton, where a horizontal-cylinder prototype already offered better performance than the stalwart up-and-down Manx.

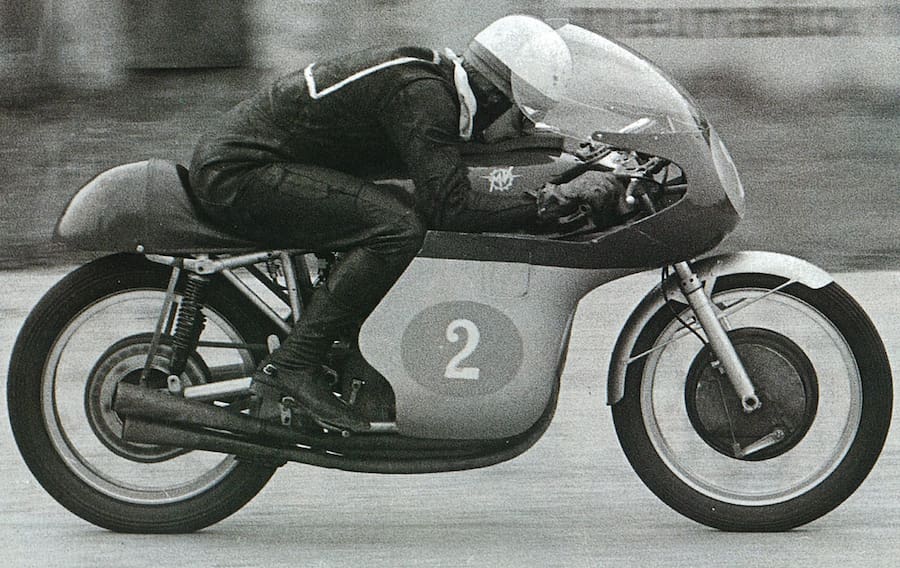

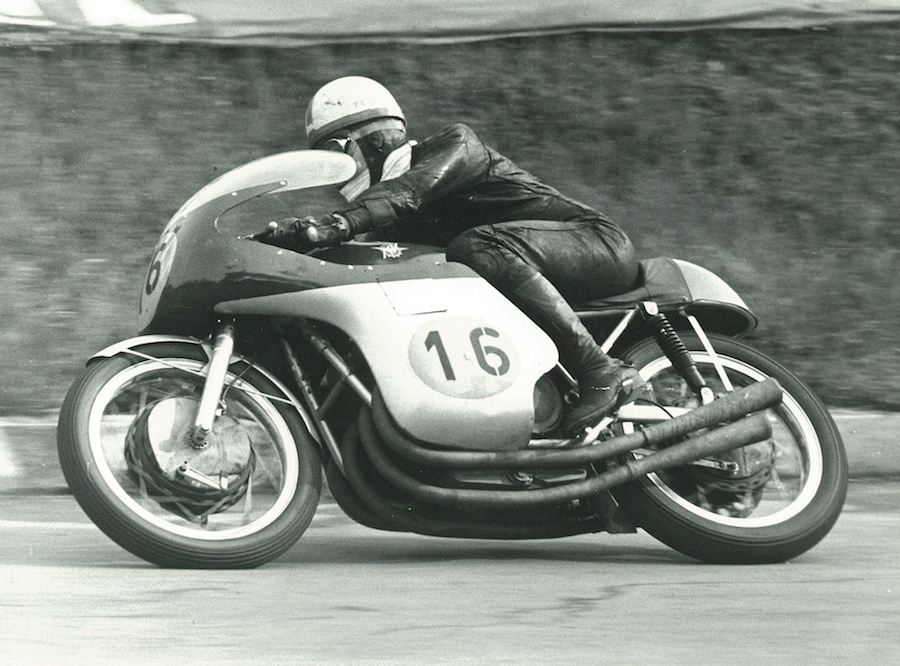

The pre-eminent racing factory was undergoing major changes, however, including the departure of long-time race boss Craig. Surtees figured (correctly) that the new Norton would never appear, and decided the MV Agusta – although in his view inferior to the Gilera – was too good to turn down. And thus was born the first of a series of partnerships that would make MV the greatest name in racing… until Honda took over at the far end of the century.

Cynics might argue that Duke’s absence from the middle part of the 1956 season after the Assen riders’ strike rather helped Surtees take the title at his first attempt – over Zeller’s BMW, and by a big margin – but Duke’s finishing record was poor, winning only one race. In any case, winning titles is about beating who is there, and Surtees did this quite comprehensively, winning the TT, Assen and Spa before himself suffering a broken arm after falling off the 350 MV at Solitude in Germany and missing the last three races. But for that, he might also have taken the 350 title.

Gilera took revenge the following year, with the MV four suffering a string of reliability problems, some caused by overheating within the huge ‘dustbin’ fairings of the day, others (according to Surtees) by sloppy manufacture. The big bodywork was banned for 1958, while in true cussed Surtees style John was putting pressure on the factory to improve the construction of its complex motor.

He had little choice but to persevere, since another turn of history had closed down most other options – including the highly interesting prospect of the Guzzi V8, the potential of which had much impressed Surtees when he tested it during 1957. For 1958, Guzzi and the other major Italian factories had pulled out – with the exception of MV.

For the next three years, all Surtees had to do was to beat the other MV riders, which he did with manifest ease. By the time he’d racked up his fourth 500 title – and third in succession – in 1960, which even he described as “a bit of a cakewalk”, it was beginning to pall. Not because he was getting tired of bike racing… quite the reverse. He just wasn’t getting enough.

The MV factory had banned John from taking part in non-championship races on his private machines, so he was restricted to GPs plus a few important international meetings. It wasn’t nearly enough to keep John happy, especially given the superiority of the MV; his main opposition was teammate Remo Venturi, although Surtees did finish second to John Hartle’s Norton at the 1960 Ulster GP. In the meantime, he had also become the first rider to win three Senior TT races in succession.

The 350 class had considerably stiffer opposition, giving Surtees more chance to show the strength and depth of his riding. He won that class in 1958, 1959 and 1960 to bring his total of titles to seven.

His technical strength had been the backbone of his success, but now MV was turning a deaf ear to his persistent demands for improvement, despite the growing threat from Japan. Along with the Italian factory’s restrictions to the number of races, this frustration triggered his unplanned and unexpected decision to quit bike racing at the end of 1960.

Surtees still loved bikes more than cars, and said later he might have been tempted back in 1962 had an offer come from Honda to develop the company’s four. But the lure of car racing was strong – with new challenges in a new technical landscape.

He’d already shown signs of a great gift, having tested Aston Martin sports cars and a Vanwall single-seater in 1959. He was urged on by influential supporters inside racing. F1 team owner Ken Tyrrell arranged an F2 car for his first ever car race in 1960 – he fought with and was narrowly beaten by the brilliant Jim Clark.

In that same year, while claiming his fourth and final 500 title, he finished second in the British car GP, only his second F1 race, and followed that by crashing out of the lead in his third race. Clearly a natural, he was set on a rapid path via Cooper and Lola to Ferrari from 1963 to mid-1966. He won the world championship in the red cars in 1964 and won admiration not only for his driving and race skills, but also for the galvanising effect he had at Ferrari, and the technical input he brought to the famous team.

He might have won the title again in 1966, but for a falling out with team director Eugenio Dragoni, who Surtees said resented his own closeness to Enzo Ferrari. Matters came to a head at Le Mans in 1966, when Dragoni told Surtees there was no car for him to drive. A furious Surtees drove directly to Maranello to speak to Ferrari, and quit on the spot.

In 1967 a call did come from Honda, but to help with its F1 venture. During the two years he spent there Surtees claimed the last of his six F1 race wins before turning to the construction of a machine bearing his own name.

Surtees retired from driving at the end of 1972 and quit team ownership six years later, perhaps worn down by a combination of ill health – the consequence of a heavy crash in a Lola Can-Am

sports car at Mosport circuit in Canada in 1965 – and the difficulties of not only of finding sponsors but also a driver good enough to satisfy such a hard taskmaster.

In retirement, Surtees remarried and fathered two daughters and a son, Henry, who followed in his father’s footsteps. Henry was moving through the ranks of motor racing, his father acting “as his mechanic, van driver, manager and sponsor, all rolled into one”, but was killed in 2009 in a Formula Two race at Brands Hatch when a wheel shed by another car bounced onto the track and struck him on the head.

Surtees was at the track, always his local circuit, as was Henry’s mother. Devastated, he considered turning his back on the sport, but

the strength of support at Henry’s funeral changed his mind. Instead, he set up the Henry Surtees Foundation to help victims of racing accidents, and also a program to assist promising young drivers.

Surtees had also been involved in the short-lived Chinese Huawei 125 team in MotoGP and was ambassador for the Racing Steps Foundation, established to promote British motorcycle talent such as John McPhee in Moto3.

He also continued riding, giving demonstration runs not only on his several MV Agustas, but also his original race-winning Vincent Grey Flash.

Puzzlingly, considering his status and achievements, not to mention a media-led campaign, Surtees was never knighted, although he was awarded an MBE, an OBE and, only last year, the senior CBE (Commander of the British Empire) for services to motorsport.

He died of respiratory failure in a London hospital on 10 March, aged 83, after a life of achievement unlikely ever to be repeated.

TRIBUTES TO SURTEES

Valentino Rossi said: “As the only one to win F1 and the 500cc championship, he did something very special. I was lucky; I met him three or four times, and he was still in good shape. I am very sorry for him and his family.”

Rossi, who flirted with F1 a decade ago, also with Ferrari, was talking to Crash.net at the Qatar tests, when news of Surtees’ death broke.

Freddie Spencer (world champion 1983 and 1985), who also met Surtees many times at classic events, revealed a special memory from his forthcoming autobiography. He was struggling in practice for the 1983 British GP, his Honda triple outpaced by rival Kenny Roberts’ Yamaha four. In the pits, awaiting a tyre change, “I felt two hands touch my shoulders. I can still feel the reassurance and firmness. I looked up, the voice said, ‘Do you know who I am?’ I said, ‘Of course I do, Mr Surtees’. He said, ‘Call me John’. Surtees continued: ‘I know you’re riding beyond your bike’s capabilities, but keep doing it, because you can, and it’s going to be okay.’ He winked and smiled, and walked away. I felt better. I went out and qualified second, then finished second in the race. John was a good friend, and I will miss seeing him tremendously.”

Many other current riders met Surtees at similar classic events, but Jorge Lorenzo regretted he was not among them. “He’s the only one winning the biggest prizes on two and four wheels, so it is sad news,” he said at the Qatar tests.

Likewise, Wayne Rainey. “I never got to meet him. I remember the first time we went to Eastern Creek, in 1991, some guy was out there on an old bike, and I watched him and thought he really knows what he’s doing. It was only later somebody told me that it was John Surtees.”

Cal Crutchlow, speaking at Qatar, said he felt “very privileged” the few times he met Surtees. “To do what he did, a record of GP wins and then Formula 1 … nobody is going to be doing this again.”

We’ll give the last word to Alan Cathcart, who met Surtees many times over the years.

“John Surtees was a hard but fair man who set high standards for himself and others which he expected them to adhere to. He absolutely knew his own mind, and wasn’t afraid of irking influential people, stubbornly sticking to his guns even if it meant ruffling feathers. If he’d been prepared to compromise or go back on his word on various occasions, he might have achieved even more than he did, especially in the murky world of the F1 paddock where a straight-shooter like John was a fish out of water. He achieved a very great deal in life in spite of his humble origins, and both the motorcycle and car worlds are very much the poorer for his leaving us.”

WORDS MICHAEL SCOTT

PHOTOGRAPHY Phillip Tooth, Alan Cathcart archives and AMCN archives