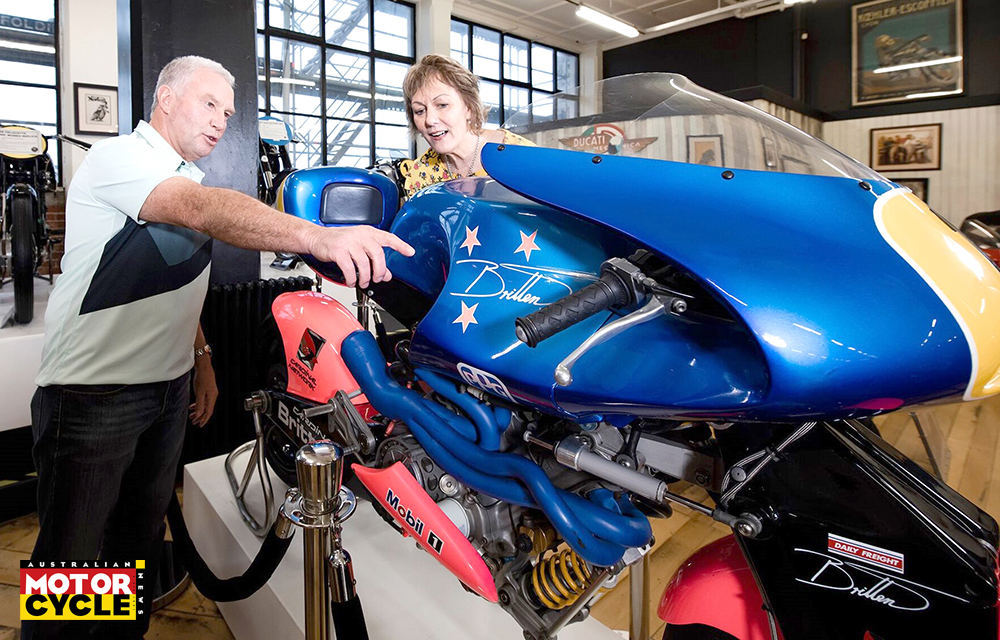

The missing piece of John Britten’s motorcycle history jigsaw puzzle has finally been put in place and visitors to the Southern Hemisphere’s largest motorcycle museum this summer can now view the full story of an amazing period of Kiwi design innovation.

Motorcycle Mecca, in the New Zealand’s deep south city of Invercargill, has expanded its comprehensive Britten display to accommodate the Ducati-powered racer called Aero D-Zero. Built in the mid-1980s, this wacky racer started John Britten’s fast-tracked but ultimately short career that pushed the boundaries of motorcycle racing design. He died aged just 45 years, in 1995, from a melanoma cancer.

Aero D-Zero joins on display the 1948 Triumph Tiger 100 that sparked John’s interest in racing in the very early 1980s; Aero D-One, a short-lived but potent Denco V-twin-powered monocoque-framed BEARS racer; the Precursor, a GP-inspired water-cooled V-twin built entirely in Christchurch that Aussie Paul Lewis took to the podium at Daytona against factory Ducatis in 1991; and the first of the last generation of Brittens, the almost birdlike Cardinal V1000 built in just a few months for the 1992 international racing season.

But it is only through the generosity of the new owner that Aero D-Zero is now on permanent display at Motorcycle Mecca. American Bob Robbins, a former Ducati BEARS racer who competed against the Britten on the high banking of Daytona in the mid-1990s, bought Aero D-Zero from Kevin Grant, owner of the 1995 World BEARS championship Britten, a few months before Grant’s death earlier this year.

Robbins owns one of the final 10 Britten V1000s, the black and chequered-flag liveried CR&S version that was raced around the world from 1994. Despite living in vastly different countries, over a 10-year period American Robbins and Kiwi Grant established a symbiotic relationship based around keeping the Britten story alive in a physical sense.

This involved Robbins leaving the V1000 he called Black Beauty in New Zealand for long periods so it could be demonstrated in tandem with Grant’s 1995 world winning racer. This meant Andrew Stroud, world BEARS champion, and Stephen Briggs, who came second to Stroud in that year’s championship on ‘Black Beauty’, were on track together.

Both Robbins and Grant regarded the Brittens as being as important to New Zealand sporting history as the various America’s Cup yachts that represented this little nation over the decades and made a country of five million a world-beater in a niche sport.

Now Robbins has the bookends of the Britten story: the bike that started a never-to-be-repeated design journey, and the final goal of that crazy adventure. So how did Aero D-Zero come about?

In the early 1980s John Britten was a hobby racer, competing in BEARS events at Christchurch’s Ruapuna racetrack on a rigid-framed 500cc Triumph twin while he ran a small lead-lighting business. The son of a wealthy local family, he had an interest in exotic motorcycles and bought a 900cc Ducati Darmah. He became friends with another Darmah owner, Mike Brosnan, a mechanic skilled in engine maintenance and performance development.

At first glance they were an unlikely pairing. Knockabout Brosnan had an occasional temper that matched his no-nonsense approach to life, while Britten had a laidback, elegant demeanour that matched his privileged background. Both were full of great ideas, but whose ideas would work and how would they get them to work?

At the time, BEARS racing was booming in New Zealand and starting to develop in Australia. Both decided to turn their roadbikes into racers. The Darmah was a good starting point regarding engine performance, but its long-wheelbase chassis was a huge handicap. So best to build your own from the ground up. The two combined their talents.

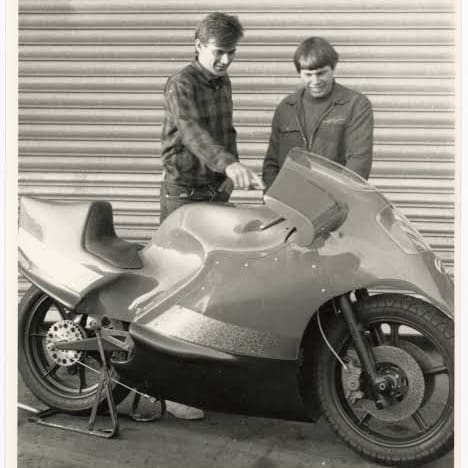

Brosnan cooked up a plan to start with an 860cc bevel engine he had acquired and construct his own lightweight, tubular-steel chassis frame around it. Britten offered to design aerodynamic bodywork based on unproven ideas floating around his mind regarding wind-force and air-lift under aeroplane wings. The result was one of the most unusual racers of the time.

The genius of this duo’s design can easily be appreciated when you line up a naked Aero D-Zero, built in a backyard in 1985, with a Ducati 916, built a decade later, and compare vital dimensions, including steering head angles and wheelbase.

The man who got Aero D-Zero and the 916 together to demonstrate the significance of what Brosnan and Britten achieved is Craig Roberts. As well as playing a major role in rescuing several Brittens from the devastating 2011 Christchurch earthquakes, he has played a big part since in preserving the Britten history. This has included piecing together the largely-forgotten Denco-powered Aero D-One and organising original Britten team members to help him get several of Britten’s other motorcycles to a stage where they can be viewed at Motorcycle Mecca

Aero D-Zero holds a special place in Roberts’ assessment of the Britten story.

“This was the start of John’s obsession with aerodynamics while for Mike it started him off as John’s first race mechanic on the entire family of Britten racing motorcycles,” Roberts says.

“To have this join the other generations of Brittens on display is an accomplishment I feel proud of but I also acknowledge that it could never have been achieved without many of the original team involved, motorcycle movers BikeTranz, and input and inspiration from Kevin Grant and Bob Robbins.”

Being hobby racers Brosnan and Britten intended to build racers that could also be ridden on the road. This is why Brosnan’s has a speedo and headlight window in the fairing.

However Britten was already evolving another motorcycle in his head as he constructed the bodywork for Brosnan. This was the monocoque that would use a more powerful, eight-valve, V-twin Denco engine, being manufactured in Christchurch for speedway racing. This is why both Aero D-Zero and D-One share similar bodywork.

The Denco involvement brought him into contact with ace machinist Rob Selby, whom he would eventually employ and would be part of the Britten story right to the end.

Over a three-year period Brosnan campaigned Aero D-Zero in local BEARS events that including speed trials on a closed road outside Christchurch. Long, dead straight but dangerously undulating in places, South Eyre Road runs parallel to similarly-surfaced Tram Road, where Russell Wright set a world speed record of 184.83mph (297.45km/h) on a Vincent in 1955 before going to the Bonneville salt flats in the US. Burt Munro set a flying half-mile record of 143.6mph (231.1km/h) there in 1957.

So it’s interesting to note that Aero D-Zero’s first run on South Eyre Road in 1987 resulted in a 234.02 km/h (145.41mph) speed. It went on to win the 1988 and 1990 speed trials with at 242.72 km/h (150.82 mph) and 247.80km/h (153.98mph).

The key to this success was Britten’s ideas about aerodynamic fairing design coupled with Brosnan’s clever engine performance modifications that didn’t compromise reliability. The fairing made Aero D-Zero look a lot taller and bulkier than it was, but the idea was to encapsulate the rider. Winglets, an early version of what is now commonplace in MotoGP, were added but abbreviated when high-speed wobbles occurred on South Eyre Road.

Typical of the do-it-yourself technology Britten employed, he sculpted the plug for the fiberglass body from a block of polystyrene and car body filler. Helping him in this was fellow motorcyclist Bob Brookland, who would play a major role in the future, including painting all the versions of the Brittens. The aerodynamics worked and Britten transferred the design to Aero D-One.

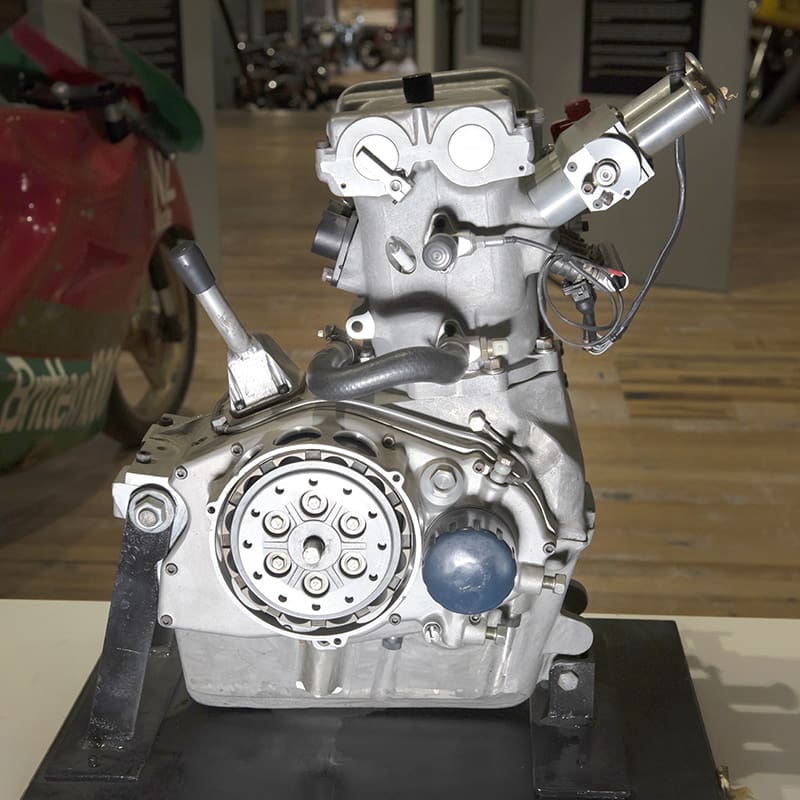

Brosnan’s engine work featured a mix of the best available Ducati performance parts. Imola cams and bigger valves added horsepower, while the standard crankshaft and conrods were blueprinted to handle the load. American Lectron flat-slide carburetors were the finishing touch in an era when Keihn flat-slides were not available commercially.

Brosnan built the chassis from small-diameter tubing similar to that used on the newly-released Ducati F750 roadbikes, while Britten fabricated the aluminium swingarm. An upgraded Ceriani fork, magnesium wheels by Morris and Campagnolo, Brembo master cylinders, AP Lockheed front calipers and a Fontana rear caliper completed the mix-n-match of exotic aftermarket parts.

While the initial bodywork incorporated lights, indicators and associated switch gear Aero D-Zero was never road registered. John Britten and Mike Brosnan’s Aero D-Zero would launch them into an all-consuming world of race engineering that ended up with a world championship and a run of 10 Britten V1000 race motorcycles.

Visit Motorcycle Mecca to put the significance of Aero D-Zero into perspective of an often-told story that, up to now, has lacked complete detail.

Britten bikes on display

Triumph Tiger 100

A very secondhand 500cc parallel-twin roadbike Britten turned into a racer in the early 1980s when the BEARS series was first established in Christchurch. He got a lot of advice and help from fellow Triumph owners Allan Wylie and Joe Hannah. Britten had a reputation for his lurid hang-off style on it. He also had a freewheeling attitude to race preparation, once welding up a broken piston and thinking he could survive another meeting on it. Britten and his mates constructed the alloy fuel tank, oil tank and seat cowling. It ran alloy wheel rims and the front brake was two single-leading-shoe hubs mounted back to back.

Aero D-One

Monocoque frame with ex-speedway Denco eight-valve engine running on methanol (Britten had thought of converting an air-cooled Ducati engine to eight valves, but the Denco option seemed easier as it was being built in Christchurch). By now the bodywork was Kevlar. Local top GP motorcycle technician Mike Sinclair, working at the time for Suzuki, advised on the chassis and assisted with sourcing GP-spec WP suspension, AP Lockheed brakes and Marvic magnesium wheels. Gary Goodfellow, an often forgotten member of the early Britten international racing effort, wrestled this methanol monster to wins including on street circuits.

Precursor

The Britten version most of the original team reckon was the one John should have stuck with and turned into a New Zealand version of a Bimota. Designed and entirely manufactured in Christchurch, it was powered by a quad-cam, eight-valve, 60-degree engine in a hang-all-components-off-the-engine design very much like Ducati’s recent Superleggera V4. Again Goodfellow was the test pilot. By now based in Canada, he raced it in Japan, Canada, USA, NZ and Europe. Later he would say: “I can compare it to a period superbike, like an RC30 or GSXR750. It was a little bit nimbler, it had lots of power and good grunt, and handled fantastic with WP suspension.” However, he also gave an insight into Britten’s mental state at the time: “John was a fun-loving guy – he was 100mph. He only had 45 years of his life but he fitted 90 years into those 45.”

Cardinal Britten

While most of the Britten team reckoned the Precursor could have been a worldbeater in the showrooms that were selling Bimota limited-edition motorcycles at the time, John had already moved on. The result was the most well-known Britten, the Cardinal (a computer engineering company sponsor) V1000. Raced in both 1000cc and 1100cc formats, it created a legend when it appeared at Daytona in 1992. Young up-and-coming racer Andrew Stroud led the BEARS race against WorldSBK-spec factory Ducatis until he coasted back into pitlane with a flat battery. Typical of Britten’s freewheeling approach to motorcycle racing, it had started out as a totally futuristic projectile brought into fruition over just a few months. The Cardinal Britten looked more birdlike than motorcycle, which isn’t surprising as John at this stage was thinking more and more about powered personal flight (one of his team at this time, Colin Dodge, would go on to play a major role in Jetpack Aviation).

Single-cylinder Britten

In the mid-1990s, single-cylinder roadracing was a hotbed of innovation, led by Ducati’s limited-edition Supermono. Britten had plans to kill two birds with one stone: make a high-performance, lightweight single that would produce 90hp and weigh less than 100kg. It would have as much relevance to roadracing as it would enduro events, including the Dakar. Only ever run in early prototype form on an engine dyno, the single, based on part of the V1000 V-twin, made 75hp. This matched Ducati’s exotic Supermono, which weighed 118kg. The project was shelved after Britten’s death while the small factory concentrated on completing the 10 production versions of the V1000. But it remains a shining example of the expertise Britten had surrounded himself with in his quest to build the ultimate racebikes.

Motorcycle Mecca

Housed in two restored historic buildings in the heart of Invercargill at 25 Tay Street, the collection boasts displays of classic British, American, European, and Japanese bikes alongside tributes to motocross and speedway (including Kiwi legend Ivan Mauger). The collection is also home to the George Begg Bunker: a tribute to a homegrown hero and a golden age in Kiwi motorsport history.

Visit motorcyclemecca.nz for more.