During the early 1960s MV Agusta and Honda dominated the 350cc World Championship headlines. Of course, they weren’t the only factories chasing glory on the racetracks of Europe. Jawa fielded vertical twins in 1960, and a year later Franta Stastny was runner up with his teammate Gustav Havel in third. With a complex bevel camshaft drive to the two-valve, twin-spark plug heads, these engines would spin up to 10,600rpm and deliver 46hp (34kW). Chasing more power, in 1963 the heads were converted to four-valve operation, which raised the engine speed to 11,400rpm. But reliability suffered.

Jawa’s twin simply wasn’t in the same class as the MV and Honda fours. It was bigger, heavier, and didn’t develop as much power. The Czech factory decided that if it was going to have any chance of taking the title they would have to build on the success of the Jawa-CZ motocrossers and produce a two-stroke road racer.

The first hint of what the Czechs were up to came in April 1964 when David Dixon reported that Jawa was working on a 500cc two-stroke square four with rotary inlet valves. Dixon’s mole in the factory told him that the racer might be ready for the Isle of Man TT, but it would definitely be completed in time for the Dutch and Belgian classics. It never happened.

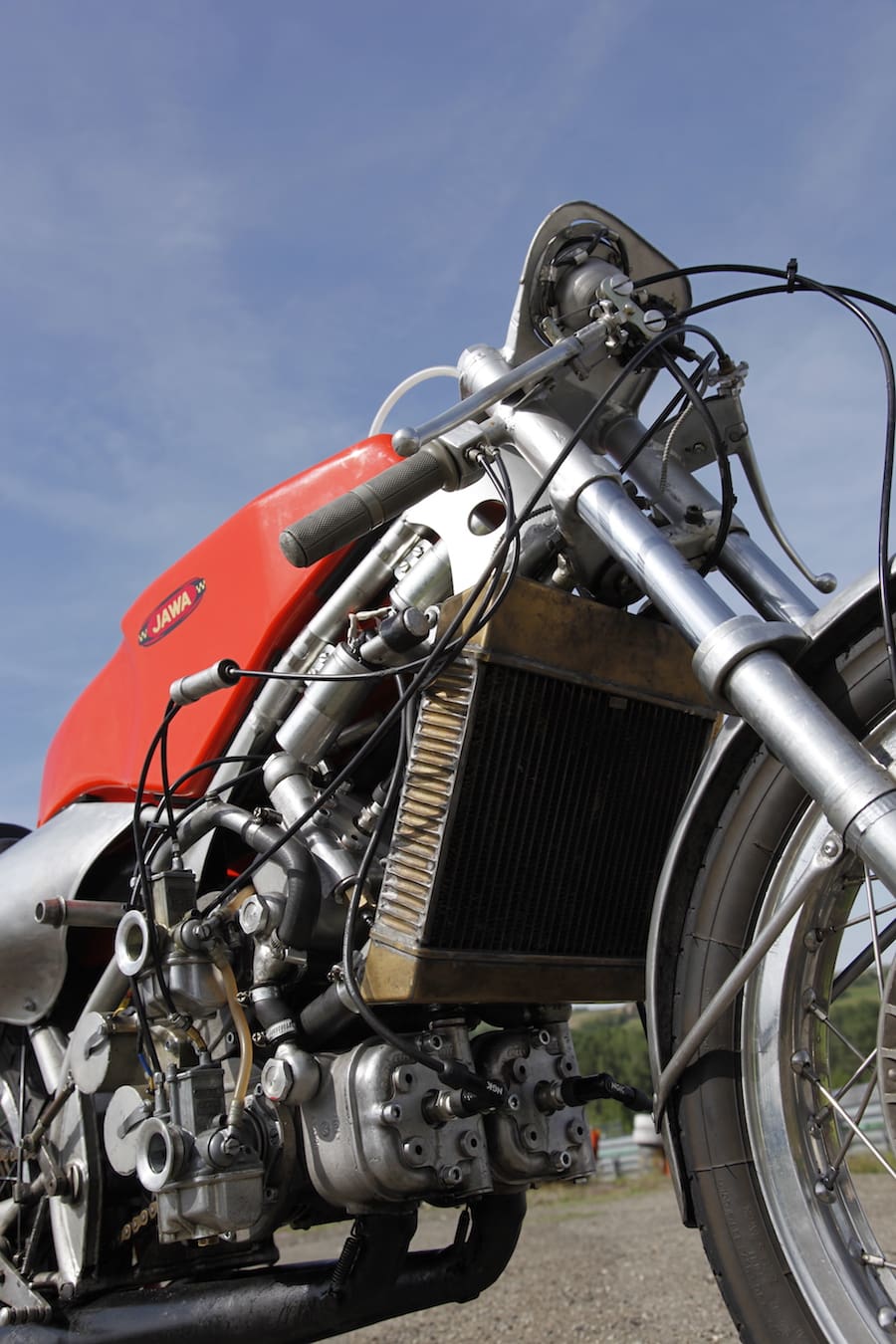

It would be another three years before the most famous Jawa racer ever built was unveiled at the Dutch GP. And it wasn’t a square-four but a stunningly complicated disc-valve V4. Designer Zdenek Tichy used two separate crankshafts which were geared together. Cylinders and heads were in light alloy, with nickel-iron cylinder liners. Each cylinder on the prototype was fed by an Amal GP racing carburettor and there were four separate sets of ignition points. The engine was water-cooled, with a simple thermo-siphon system.

With a bore and stroke of 48 x 47.6mm the capacity was 344cc. The Jawa ran a stratospheric 16:1 compression ratio and was claimed to pump out an impressive 60hp (44.2kW) at a spine tingling 13,000rpm. Power was available from 9000rpm there was a dry clutch and seven ratios in a cassette gearbox to keep the motor on the boil.

Officially designated the Model 673, the engine was slotted into a frame based on the one used for the DOHC racers. Weight was kept down by using plastic instead of fibreglass for the fairing, oil and petrol tanks, seat and mudguard.

But the Dutch GP was no fairytale debut for Jawa. Fifty years ago, strokers were a lot less reliable and the V4 was plagued with partial seizures during practice and even after a complete rebuild it still seized during the race. It was back to the drawing board.

After their return to Prague the technicians came up with a couple of ideas to cure the piston and main bearing seizures. The first job was to fit a pump to circulate the cooling water. Then they tried an oil pump to supplement the petrol-oil mix lubrication. The Amal GPs were changed for four Dell’Orto carbs.

Development continued with Franta Stastny in the saddle. At the 1968 Czechoslovakian GP at Brno, Stastny finished third behind Agostini on the MV and MZ works rider Heinz Rosner. It looked as if the development work on the new breed of Jawa racer was finally paying off. Stastny was certainly impressed with the speed – the V4 could top 260km/h – but he was still not sure when it would seize and fling him off.

Although Franta Stastny had been a loyal Jawa employee, the factory decided that if they were going to beat Agostini and the MV to the world title they needed a rider who knew how to handle a V4 stroker. They must have though that the gods were smiling on them when Yamaha disbanded the factory race team after the 1968 season.

Bill Ivy – who won the 125 World Championship for Yamaha in 1967, and was second in 1968 in both 125 and 250 classes after a little misunderstanding with Phil Read – said that he was finished with motorcycle racing and bought a Brabham car to compete in F2. But in spite of impressing the likes of Jackie Stewart and Graham Hill with his natural ability he couldn’t get a decent sponsorship deal. He needed money – and Jawa needed him.

Standing only 160cm tall, Little Bill had stunned the motorcycle world when he did a 100.32mph (161.45km/h) lap of the Isle of Man course on a 125cc Yamaha V4 while on his way to winning the 1968 TT. He had seen the Czech V4 and spoken to Franta Stastny at the 1968 Ulster GP, where Ivy had won both the 125 and 250 classes ahead of teammate Read. Stastny warned him that the Jawa was not fully sorted and had seized many times in practice, but Ivy retorted that the Yamaha V4s seized as well and it didn’t bother him.

Ivy flew over to Prague and looked around the factory and race shop. He could see that the Czechs didn’t have anything like the resources of Yamaha, but he was impressed by their enthusiasm. And after testing the V4 he was also impressed by the bike’s potential. He signed for Jawa.

By now the V4 had a new frame, the twin rear shock absorbers were adjustable for ride height and used compound springs. A Ceriani-type fork looked after the front end, with a massive double sided, twin leading shoe magnesium drum brake up front and a smaller single leading shoe drum to steady the rear.

With a rider of Ivy’s calibre on board the V4 really started to show its potential – handling, braking and speed were all top rate. But the Jawa still had a tendency to seize when the throttles were wound wide open. Fortunately Bill Ivy could whip in the clutch lever quicker than a rat trap can snap shut. This was just as well because he needed his super-quick reactions when the Jawa engine shrieked in anguish on lap 10 of the 1969 Italian GP. But by the time of the German GP at Hockenheim it looked as if the Czech technicians had sorted things out and Ivy gave Ago a real fright, chasing him all the way to the flag and lapping the field in the process. Stastny on another V4 finished in third.

Ivy was on brilliant form at the Dutch GP. Although he started badly he quickly caught the World Champion’s MV and dived in front. He held the lead until the V4 became a V3 and Bill slowed as the crowd groaned in disappointment. Ago took his chance to nip in front. But the Jawa’s fourth pot suddenly chimed in and Ivy started closing the gap.

The Assen crowd were on their feet as the dashing Italian and the little Londoner screamed around the track, the gap closing with every lap. Ivy swept into the lead on lap 12 and the fans went wild. Ago tried his best but he couldn’t hang on to the Jawa’s four tiny tailpipes. Little Bill and the screaming V4 pulled away to open up a comfortable lead. The race was in the bag… until the Jawa went back onto three cylinders and Ivy was forced to settle for second place.

Jawa technicians decided that electronic ignition might finally sort the V4. Constant development had increased the power output to 70hp (52kW), equivalent to 203hp (151kW) per litre. There was even a 351cc version being prepared so that Ivy could take on Agostini in the 500cc class. It looked as if Little Bill would at last have the machinery to stop Agostini having it all his own way.

Their next meeting would be on 13 July at the Sachsenring for the East German GP.

Bill went out for the first practice session the day before. He was warming up the engine and was doing about 130km/h on a soaking wet track when he went into the left-hand bend that would take him through the village of Hohenstein-Erstthal. Some spectators said that he was leaning over the petrol tank, his left hand feeling the engine for a cold cylinder because it was not running on all four. Others said that he was adjusting his goggles or trying to buckle his helmet.

Then the lower left side crankshaft seized so suddenly that Little Bill was thrown into the air and bike and rider slid along the road. His helmet came off before he slammed into a low concrete barrier that wasn’t protected by straw bales. Ivy sustained severe head and chest injuries. He was rushed to hospital but never recovered consciousness. The Jawa team were devastated at Ivy’s death and Stastny withdrew as a mark of respect. After the race Agostini announced that he had won not for Italy, but for Bill Ivy.

Ago had racked up eight straight wins and the championship was in the bag after the Ulster GP so he didn’t bother racing in the final two rounds. Silvio Grasetti took over the V4 for the Italian and Yugoslavian GPs. Jawa’s V4 only had one victory and that when Grasetti won the Yugoslavian GP, the final round of the series. But it was a hollow victory – none of the top bikes or riders competed. Then Stastny found out that Ivy had been paid a superstar salary, while after 15 years as a factory rider he was still only getting a Jawa employee’s wage packet. He felt insulted and resigned, leaving to work as a television sports commentator. His last race was on a Yamaha. Jawa’s V4 bid for glory was over.

So who’s bike was this?

According to the owner Antonin Kružík, it’s rather hard to say

“Don’t trust anyone who says that he’s got the Bill Ivy bike,” says the owner of this Jawa V4 Antonin Kružík. “Three V4 racers were built, along with enough spare parts to make another one. When designer Zdeněk Tichý retired he bought the only original and complete bike left. That is now in the National Technical Museum in Prague, but it’s not a runner.”

Just like this example, the bikes that can be seen at classic racing events were constructed from a mix of original and newly manufactured components. “Some have more original parts than others, and the owners will admit it,” continues Antonin.

Words Phillip Tooth Photography Greening Archive & PT