The road to Mallala near Adelaide is a boring affair – as straight as a die. I was on a 1993 CBR600 heading back from the track and my mate was on the then new first model 900 Fireblade. We were flat out lying prone on the tanks, speed rising all the time. I was slipstreaming him and just hanging in there. As he gradually pulled away I remember thinking how futuristic that bike looked, and that memory has stuck with me over the years.

In 2007 I rode in the WSBK championship on the then current underseat pipe version of the Fireblade. To be honest I hated every minute of that animal – it was more like riding a seesaw than a motorcycle. It was super aggressive and turned into a wheelie monster when you breathed on the throttle, and the next minute the rear wheel was dancing in the air under brakes.

The last Fireblade I rode was Casey Stoner’s 2012 model roadbike. Essentially the same as the 2016 model, it was sitting at Honda HQ out in Campbellfield, Victoria, gathering dust until they sent it to me in Tasmania to cut some laps around Symmons Plains Raceway. After having ridden all the 2016-spec superbikes, I could see that in standard form the old Blade was technically below par.

However, even with the deficits of age, last year’s bike still sold incredibly well, and won the Australian Superbike Championship. That nearly 10-year-old machine proved one thing – that you don’t need to have all the modern features to get healthy sales figures, and sometimes just a good name and pedigree can get you through.

Thankfully though, this new reforged Honda is truly back in the hunt for the hearts of street riders and track racers.

Honda hasn’t rebuilt the CBR from the ground up like Suzuki did with its new GSX-R1000. Instead, it took what was already a very good base and looked at improving every aspect of it. I don’t mean a bit of new paint here and a new gold calliper there like in the past, but by improving the four elements that make a superbike work: power, weight, handling and controllability.

The first thing you notice when you get up close and personal with the new bike is its size. It’s tiny, even compared to the old Blade – which wasn’t a big machine. It’s narrower across the seat and the front fairing has been reduced to lower the aerodynamic coefficient but still give the rider just enough wind protection.

I found that for my 175cm frame there was enough shelter while I was blasting down the Phillip Island straight at over 290km/h, but I had to tuck in. I’m not sure what bigger riders are going to think, but I’m guessing that only a small percentage will be doing over 290 clicks.

That reduction in physical size has been achieved by changing everything you can see, touch and feel on the bike – and that’s major news as it’s the first time since 2008 we have seen any kind of shape change on Honda’s flagship 1000. One of the most refreshing additions to (literally) brighten the package up is the new TFT dash.

There are a few bikes out now with the TFT dash fitted, and I really like them. The Honda unit is particularly good as everything is clutter free and easy to read. As on the units from other manufacturers, you can move the information around, letting you choose what you want to be displayed rather than what the factory has decided is a good generic set-up.

As you delve deeper into the 2017 model it’s easy to see that the detail and quality Honda has always produced is still there, but this time around they’ve taken things a step further. The fairing gaps are perfect, nothing sticks out, and there’s no excess in sight. But maybe it’s the things you don’t see that show just how hard Honda has worked.

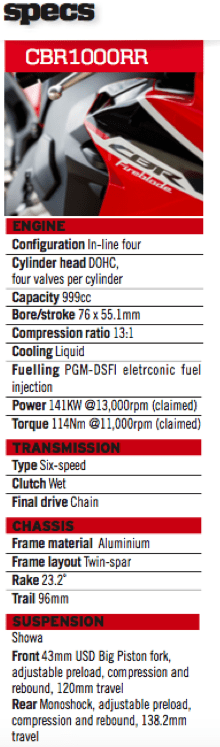

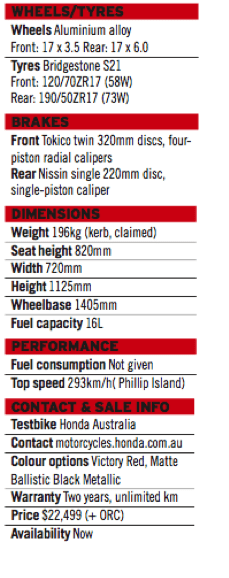

The frame is ostensibly the same and geometry remains unaltered with a 23.2° fork angle and 96mm of trail, but the bike has been on a diet with reduced chassis wall thickness that saves 300g but leaves transverse rigidity unchanged.

The frame is 10 per cent more flexible in the torsional plane, which works to deliver a faster-reacting chassis. A further 600g is saved with the new subframe, and the swingarm didn’t escape the designers’ eyes as its now stiffer but 300g lighter.

New front Tokico four-piston opposed, radially mounted brake calipers are more rigid, 150g lighter and do without hanger pins. Newly developed brake pads are fitted, and these have a greater performance parameter at higher temperatures than the standard old pads. Wheels are lighter by 100g, and even the alloy radiator has shed 100g.

The extremities weren’t the only items to get the treatment, though – the engine also went on a 2kg diet, meaning the new CBR has dropped a whopping 15kg overall.

At the same time, Honda’s engineers fettled some extra power into the Fireblade’s 999.8cc in-line four-cylinder engine. An extra 8kW were found and a raised rev ceiling delivers peak power of 141kW at 13,000rpm, with peak torque of 114Nm delivered at 11,000rpm. Not only is it light, but the power output is also in the ballpark of other superbikes. To get these gains would usually stress a motor if the internals weren’t beefed up, so the crankshaft, valve train and transmission all use higher spec materials than the previous model, and all of this helps keep the new Honda engine as reliable as the old one.

But the biggest change in this year’s model has to be the all-new electronics system. The new Blade uses a Bosch inertia sensor (like almost every other major manufacturer) to measure five different axes and calculate the bike’s attitude 1000 times per second. That info then gets fed through to Honda’s own in-house-designed software where the ECU sends out recalibrated information to the throttle bodies and new lighter ABS system, hopefully keeping the package on its correct trajectory under acceleration or braking.

The Honda system has five pre-set maps, two of which can be modified by the user. These five maps can be used on the fly by hitting the selector switch and simply closing the throttle.

Map one is used for fast or track work, map two for fun riding, and three is a soft map for comfort. Now don’t get confused at this point as we are not talking about suspension, just engine control – while the up-spec SP version does come with Öhlins semi-active suspension, there are no such goodies on the standard Blade we tested.

The other two modes allow the pilot to modify the maps in three areas. P is for power which gives a choice of five settings from mild to wild, T is for torque (nine settings), and EB is for the adjustable engine brake system (three settings).

The torque maps are used to control wheel spin just like a traction control would by closing the butterflies down automatically when the rear wheel speed sensor picks up a speed differential from the front wheel. How much support you get depends on the map you choose. It’s a common system nowadays, and it’s good to see it implemented in Honda land.

All the new bling looks good on paper, but as always the proof of the superbike pudding is in the riding. And heading out on the Phillip Island circuit with just eight other riders for the day was going to give us a good taste of what the new CBR1000RR was like.

The first thing you notice when you tweak the throttle is how fast the new Blade feels compared to the old one. It’s a big step ahead in the speed department, and power delivery is linear.

Honda claims a 14 per cent improvement in power-to-weight ratio, and I’m not going to argue with them. I think the old Blade had a slightly easier power delivery to manage exiting a corner on the lean angle, but that would be due to the lack of power it had compared to this one. I wanted to use the maps to dull the power in the low throttle opening area to counteract that feeling, but unfortunately, the way the maps work it seems for now they only vary in the higher rev range, making a massive feel in difference there, but not at first twist of the throttle.

I played with the torque maps to try smooth it out, and I did achieve a better feel, but ended up losing too much drive with a smooth exit feeling, so reverted to what I thought was the best setting: map one, Honda’s track-oriented set-up.

The chassis was track-oriented from the outset, feeling pretty planted with just the stock settings. I had a few small issues while riding the stock set-up, but nothing you wouldn’t expect from a bike straight out of the crate.

I was running slightly wide in the fast corners, bottoming in the braking area down into the tight Turn 9 right-hander and experiencing a bit of front patter through Southern Loop. These are all problems that wouldn’t necessarily occur on the road, and in fact the standard settings may well be perfect in that environment. On the track, however, I got Paul Free from MotoLogic to wave his magic wand over the standard suspension (see breakout) and I was suitably impressed with the outcome.

After a few tweaks, only using the external adjusters, I was very happy with the bike and its handling. It finished the turns better, the pattering was gone, and while I was still close to the bottom in the braking area, it improved markedly.

One area I still struggled with on the track was the ABS. It worked well almost everywhere, but through Stoner Corner where I was feathering the lever at high speed and getting a bit of a freewheeling sensation, the Blade incorrectly thought I had no grip. I got used to it after a few laps but it would be nice to be able disable ABS for serious trackdays. For the road, the system should be kept on of course, because it will save your butt.

I loved the ergonomics of the bike and I fitted it like a glove, a first for me with the Honda. I didn’t get tired at all riding it, and the change of direction was amazing. It almost felt like a 600 in the way it held its composure when it was being flicked around, and that’s why I enjoyed it so much.

At the end of the day my Pirelli Diablo Corsa rear tyre was smoked – I had worn all the tread off the left-hand side and done 60 laps. I’d had a hell of a lot of fun and learnt a lot about the new Blade. Firstly, it’s not so much new as massively modified to be closer to the WSBK racers. Its electronic package is a reasonably good first effort, especially when you consider it’s the first time it has been fitted to an in-line four Honda. The bike has gone from being a slightly outdated model over the past few years to a serious contender for superbike buyers. Oh, and once the Crankt Protein Superbike team get on top of these machines, the competition in the ASBK had better be well prepared.

TEST Steve Martin