It was Friday arvo and the Adventure Sport and I were heading off for Kelly Country. To avoid long-weekend traffic, we skirted the eastern edge of Melbourne to the Black Spur. An hour and half later, at the top, it was raining, the fog was rolling in and the light was fading – fast. Did someone say adventure? Bring it on.

When the bike had arrived, I’d been struck by its sheer presence. Gleaming, pearlescent white, trimmed with deep shimmering red and blue Tricolour decals popping in the winter sun. My next thought was, where’s the ladder? This thing is tall. With a seat height of 900mm (and that’s on the low setting), it’s a big bike, but it was when I was tucked behind the wide tank and tall screen I began to appreciate its big-bike comforts.

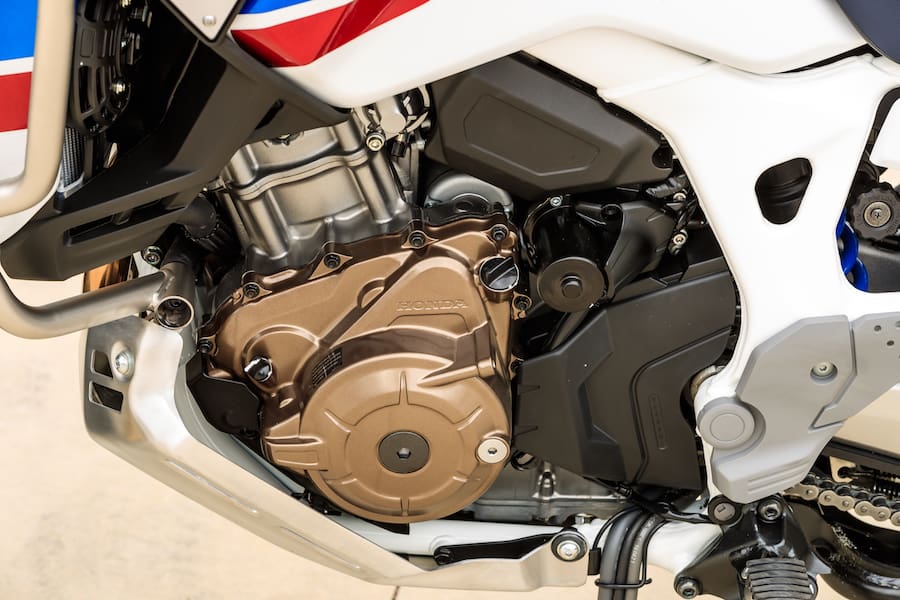

And it’s roads like Victoria’s notoriously fun Black Spur that had me falling for the Africa Twin’s engine. A little cranky, a lot grunty and a smidgen lumpy-licious! Often Honda makes engines that are so good, they tend to lack a bit of personality. Not this liquid-cooled 998cc parallel-twin.

Thanks to its 270-degree firing order, the off-kilter V-twin-like engine just talked to me.

I got the feeling the engineers put a lot of effort into the intake noise for rider feedback and to provide its owner with that special tingle. It’s quick, too. If you want to play silly buggers, leave yer licence at the door. The donk is a compact and narrow thing, and the 2018 models get an upgrade to the airbox to improve the mid-range, which is where the Adventure rider needs it. This is a rider’s motor, no doubt.

On the black top, the Sports part of its moniker shines. Stable, accurate road manners and a more than respectable clip in winding mountain roads. The suspension offering is about right for my 80kg with a small bag on the rear rack – which is a bit small; ample for one-up but stubby for two – and not many riders will be spending their hard-earned on suspension upgrades.

By Mansfield it was dark, and the magic road through to Whitfield was shrouded in thick fog. Yep, it was still persisting it down. It’s one of my favourite roads and I thought I knew it well. But with vision to 50 metres to a solid white wall, I was mistaken. And what usually takes me an hour took almost two.

Getting a handle on the DCT system saw me going back to the beginning and looking up what the hell it was. After poring over the owners manual for the best part of an hour, I started to get it. So the system consists of two clutches, one mated to the odd gears and the other to the even. It’s neither automatic nor manual.

With a standard gearbox, each time a clutch is disengaged to change gears, a slight pause in acceleration – and therefore traction – occurs. By employing separate clutches for every second gear, Honda is effectively able to achieve a seamless-shifting gearbox.

Whether the rider chooses to change gears manually (operated off the flappy paddle things on the left switch block) or through the system’s automatic capability, when the electronically operated DCT detects an upshift it engages the next gear before releasing the clutch on the previous one. All the rider feels is smooth, consistent acceleration.

It’s split into two modes, Automatic (AT) or Manual (MT), and gear changes can also be manually made with the paddles in any mode (and at any time). But it’s not that simple. In the AT mode there are two sub-modes, S for sport and D for drive (or dull?). The owners manual has a flow diagram that I can’t make sense of, but the three-way switchable S mode offers three different levels of so-called sportiness that adjusts when the system chooses to grab another gear. It effectively allows you to hold revs longer in each gear for more sporty performance.

Changing between modes is as easy as pressing a switch on the right switchblock, and can be done on the fly. I preferred the S mode in the top position, which held the revs the longest. I could flip up a gear when I wanted it that way. Early on, I was convinced that I’d have the bike in MT mode on dirt roads, but that didn’t prove to be the case. Trusting the technology and going with it worked best for me.

Flip the stand down, the engine stops and the transmission defaults to neutral even in the manual mode. Riding a big bike that instantly reverts to neutral proved challenging in technical off-road stuff. But I eventually worked out that employing the park brake (which takes two hands) to keep it in one place, or engaging it like you would a clutch to inch it backwards, proved a handy solution.

There’s also a big button to the right of the main dash emblazoned with a big ‘G’. Is it G for grunt or G-spot? Maybe S for sweet-spot might have been the go, but the DCT system had already pinched it. Whatever it stands for, the idea is to improve throttle response at low revs in off-road situations. On the road with a pillion on board, the G-mode would just cause lots of helmet clacking, but off-road it makes those essential wheel lofts or rear slides a cinch.

DCTs have been in the car world for some time. But this wasn’t a ‘let’s slap it on and see how we go’ type thing, Honda adapted it to motorcycles with the intention of joining the rider and the machine to increase riding pleasure; it’s what Honda (and Mazda, for that matter) calls the Jinba Ittai. Honda engineers have given this DCT version a lot of thought, with development and off-road use high on their agenda.

So, after a day off the bike, I went exploring some forest tracks in the King Valley above the Edi Cutting. Constantly aware there is a fine line between stupidity and adventure (amplified by riding alone), I kept a close eye on my maps and my Plan B.

This is a true off-road contender. If the rider has the skills, a bit of height or heft to chuck it around, it will reward in spades. The Africa Twin was conceived as a bike for the bush, forgiving when required, aggressive when needing to commit, accurate when hearts approach mouths, and tractable when the surface gets iffy. Protection provided by the high-set standard crash bars will save a lot of broken plastic bits up top… as I found out.

It took a while to find a standing position that suited me in the tight uphill stuff; the ’pegs were set a little too far forward to get a good grip on the bike, but after a bit of experimenting I found that the spacious seat is cut to allow the rider to slip back slightly, and stand to attack corrugations and the ups and downs of the track.

Both wheels are shod with tube-type tyres. I’m not sure if this was done to make off-road flats easier to fix, to expand the choice of rubber, or to control costs. The test bike was fitted with Pirelli Scorpion Rally tyres, on a 18-inch rear and a 21-inch front.

I expected the seat to be a little too firm, but seven hours in the cockpit proved otherwise. The tank shape allowed me to be reasonably well protected in the soggy and cold weather, but I found I was a bit short for the non-adjustable screen and got caught in a bit of rumbling turbulence. Peeking up to the height of a taller rider (bastards), I could get cleaner air.

This Big Bird of the adventure bike market is for the tall or the bold. Turning the bike around for yet another pass at the photographer was a good way to build up my low-speed confidence; initially tippy-toeing on rough roads on a bike that didn’t belong to me got my freckle a little puckered.

Honda offers three rider modes; Tour, Urban, Gravel and a fourth, fully customisable mode called User. And within each of these modes, the power output, engine braking and traction control settings can be customised to your liking.

The level of engine braking is controlled via the rider modes, and when at the highest setting it is almost intrusive. On dirt roads, blip the downshifter located on the left switchblock and a compression lock-up is not far away. On steep downhills, of course, engine braking is an absolute necessity, and set up this way it significantly increases controllability.

My return trip took me further to the east, dropping down into the High Country on the fast dirt of the Jamieson-Licola Road, slipping into the back door of the historic gold mining town of Walhalla. But it was when the road opened up on the homeward stretch that I wanted cruise control, still curiously missing on the updated machine. The left switchblock is already crowded, so that’s the only reason I could think why Honda opted not to include it. It would have been a nice help to check off the highway kays.

Brakes are matched to the bike nicely, too, though I’d like a little more feel on the rear, which was a bit on or off. ABS on the front is full-time, while the rear can be turned off via a switch on the dash when stopped.

There is always more front-end braking grip on the dirt than you think there is and I’m a fan of front-wheel ABS off-road; it allows me to explore more of that grip with less anxiety.

The seven-way adjustable traction control is state of the art and switchable on the fly. Hold the toggle switch for three seconds and it’s off. When on, flip it and the levels scroll through;

default is Level 6, returning each time the engine is switched off. There is no indication of the system’s intervention either; the bike either slides controllably or digs in and bundies off.

LED headlights are the future and the CRF sports a pretty good set, with ample penetration and spread. And when every shadow threatens to jump onto the road in the gloom, I reckon you can’t have enough illumination.

The five-setting heated grips (standard on Adventure Sports) got a workout and the on/off switch located within the grip is a nice touch, though I did find the bright green light distracting at night.

The left switchblock is busy, and by the time I had to give the bike back I’d waved to lots of motorists as I changed lanes. More often than not, I’d hit the horn instead of the indicator and found the best recovery was to wave a g’day instead of an apology.

I love the self-cancelling indicators. But the jury is still out regarding the on-all-the-time function; both indicators shine solid, full-time, until you indicate. On balance, I reckon it will be safer and would save my breakfast pork more often than threaten it. But I do have a niggling concern that the tin-toppers will glance up between texts, see an on indicator, take a swig of coffee and blunder out in front of me.

Small niggles aside, the new Africa Twin Adventure Sport is no pretender; it’s a serious contender for the very top of the dirt heap. It’s a true dual-sport bike and my new mate was handed back with an extra 1100 kays on the clock and some dirt wedged deep inside the workings.

Big adventure bikes need a positive approach and this one’s no exception. I’m hard pressed to think of a road type it wouldn’t shine on given that this bike is probably far more capable than the majority of riders who’ll throw a leg over it. And having long ones will help!

TEST Andy ‘Strapz’ White

PHOTOGRAPHY Mark Dadswell