Harley-Davidson’s decision to shut down Buell in 2009 brought an end, first time around, to Erik Buell’s dream of breaking the conventional two-wheeled template of American motorcycle design. The bankruptcy in 2016 of his successor company, EBR, after a run-in with his Indian partners, could have been the final curtain on Erik’s ambitions, but the past three decades have shown that Erik Buell is a survivor and can’t be counted out.

Buell has long swum against the tide of transatlantic conformity, firstly in creating a range of air-cooled pushrod V-twin sportbikes, each with avant-garde chassis offering a level of handling and performance at odds with the American Way of motorcycling. Harley meets Bimota.

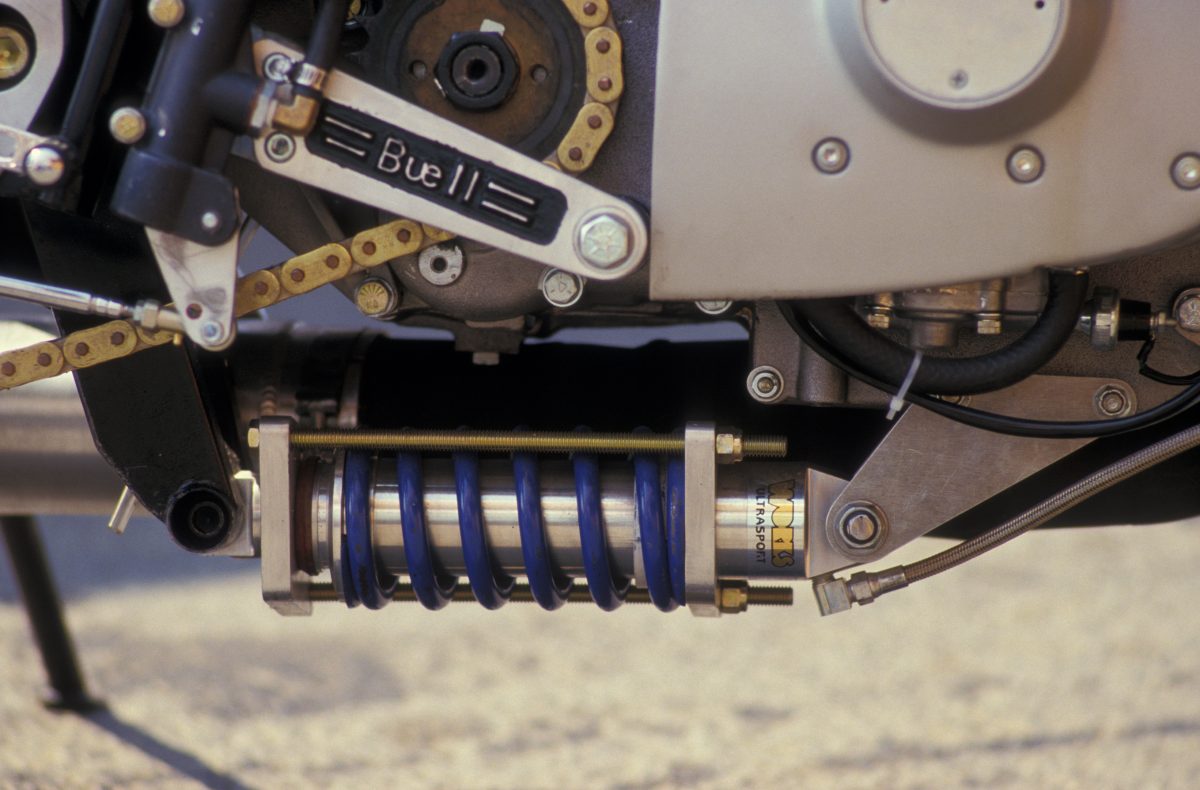

The Buell RR1000, launched in 1986, was the first bike to incorporate Erik’s radical ideas on chassis design, and was powered by the iron-barrel Sportster-based Harley XR1000 engine. It set the direction for future Buell bikes, incorporating Erik’s rubber engine mounts that permitted the vibratory Harley engine to be mounted as a fully stressed component in a light but sturdy tubular steel spaceframe. The frame featured a monoshock rear-end – another first for a Harley-engined motorcycle – but with the suspension unit slung horizontally beneath the motor, and operating in extension rather than in compression as on most other motorcycles, even today.

In designing the frame, Erik incorporated his own personal engineering principles, which he calls the Trilogy of Technology. This comprises three fundamentals: centralising mass to maximise responsiveness; chassis rigidity to ensure more predictable handling, obtained by using the engine as a fully stressed component; and low unsprung weight for superior suspension response. These distinctive design characteristics remained in all future Buell designs. “It doesn’t matter what materials you use, whether it’s a tube frame like our earlier bikes, or a fuel-in-frame aluminium one, those are the principles that matter,” Erik once declared.

Buell worked in Harley’s R&D department from 1979 to 1984, rising to senior engineer in charge of advanced projects, before going his own way to concentrate on his love of racing, only for a rule change to call a halt to his two-stroke project. “That left me in deep trouble – but even though I was flat broke, there was no way I’d go back to Harley under such circumstances!” recalls Erik.

“Then in 1986 I was commissioned by Craig Vetter to build an XR1000 Harley concept bike for custom shows, and it all started from there. I rubber-mounted the engine so it wouldn’t shake your teeth out. I built a spaceframe chassis using correct steering geometry so it handled reasonably well, and I covered the result with some futuristic bodywork. That was the first Buell RR1000 Battle Twin, and reaction on the show circuit to what was only intended to be a one-off project bike convinced me to put it into handmade production.

“It was hard starting a manufacturing facility in my barn, especially with no money, but I managed to get 25 firm orders from Harley dealers, who wanted to expand their range with a sportsbike, and Harley agreed to supply me with motors. So we started production in 1986, and the 25 bikes became 50 in all, each fitted with the four-speed XR1000 iron engines – but then stocks of these older motors ran out.”

Talking with Erik about those first Harley-powered Buell streetbikes took me back to the summer of ’86, when I became the first journalist to test-ride a customer Buell. One of my US track rivals, Devin Battley, owned a Harley dealership in Maryland. He’d had sufficient faith in the Buell design that Erik appointed him as his fledgling company’s export director.

That’s how I found myself spending a mellow autumn day road-Hogging around the Maryland countryside on Devin’s Buell RR1000 Battle Twin, bearing chassis #001. Yes sir, the first ever Buell streetbike, freshly delivered from Buell Motorcycle Company’s tiny workshop in the depths of the quiet Wisconsin countryside, not far from Harley’s HQ in Milwaukee.

Erik was taking a big gamble back then, in the days before America discovered sportsbikes, to find enough non-conformist Harley enthusiasts to make the idea of building a 16-inch-wheeled, single-seat, monoshock Harley street racer a viable proposition, even in limited production form. But he got full marks for trying, and Harley-Davidson helped by providing engines and various ancillaries, valuable computer time to assist with R&D, and official approval.

In spite of what was a steep US$12,495 list price, the Buell RR1000 was a desirable, effective and highly idiosyncratic streetbike. Considering Erik had never made a street-legal machine before, it was clear he had a lot to offer the world of motorcycling, even if his revolutionary chassis was wasted on a heavy and dated Harley engine.

So the bike I rode was a strange mixture of old and new – a modern chassis with a vintage-era engine that even the race-style SuperTrapp exhausts (worth 5kW) couldn’t disguise.

With meaty acres of torque peaking at 4400rpm, and an output of 57.5kW at 5600rpm (up from 50kW for the stock XR1000), this was still a slugger of an engine, better suited to cruising than being taken to the limit on Racer Road, as the Buell frame allowed (no, encouraged) you to do.

The four-speed gearbox had an extremely slow, long-throw change action, with a guarantee of hitting neutral between first and second if you didn’t stab the lever twice, while the bulbous fairing required an unsightly and intrusive bulge on the right side to enclose the forward one of two 36mm Dell’Orto carbs.

A well-triangulated, straight-tube, minimalist spaceframe in chrome-moly tubing weighing just 11.8kg wrapped the V-twin, whose centralised mass was aided by a hefty but effective car-type silencer positioned beneath the dry-sump motor, as on all future Buells.

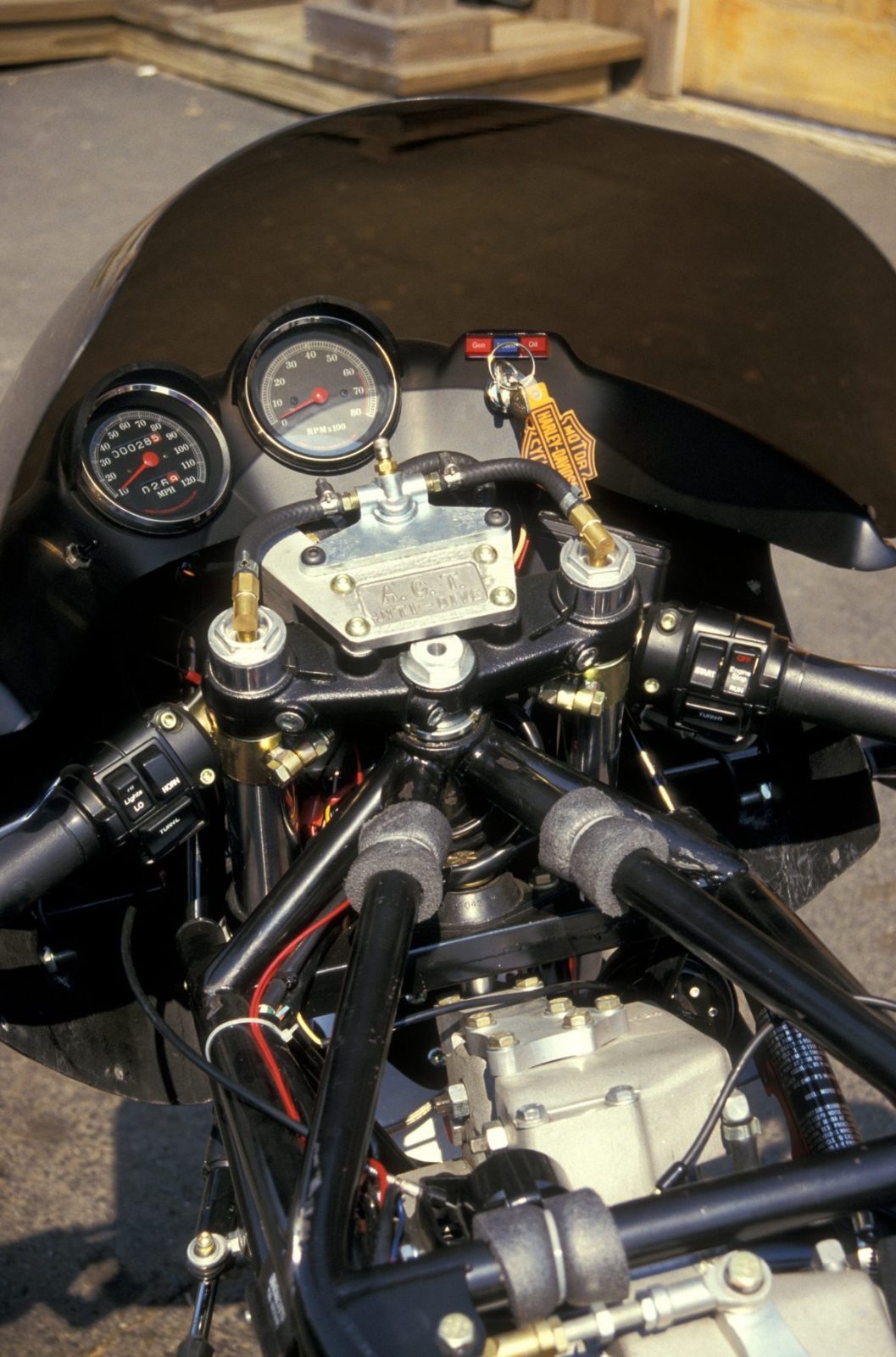

Front suspension incorporated a 4l.3mm Marzocchi MlR fork fitted with Buell’s own design of electrically operated anti-dive; when you gripped the front brake, a solenoid was triggered to reduce the internal capacity of the fork legs’ air cells, reducing the likelihood of bottoming out the fork, but not at the expense of damping performance. So the suspension didn’t freeze, as on other comparable systems of the day. Nor did the RR1000 sit up and head for the hedges if you touched the brakes in a turn, as on so many bikes then fitted with briefly fashionable 16-inch front wheels. Part of this was due to Buell’s steering geometry; with a 25º head angle, but no less than 117mm of trail, Buell had produced an adequately quick-steering yet stable bike that was a delight to flip-flop through the flowing turns of Devin’s local Racer Road – though I suppose I shouldn’t have tried that with the Highway Patrol behind me. Fortunately, the patrolman was a Harley rider and Battley customer, so I escaped with a caution. Still, my fault for not looking in the mirrors…

Speaking of which, mirrors on a Harley back then were rendered totally ineffective by vibration from the non-counterbalanced 45º V-twin, but not on the Buell; Erik had cleverly mounted the engine to dampen out most of the vibes. When I fired up the RR1000 and looked at the mirrors, there wasn’t a tremor. Incredible.

When I blipped the throttle they stayed almost completely still, thanks to Buell’s patented Quadrolastic engine mounting system, which later adopted the Uniplanar name. Since a Harley engine with its knife-and-fork crankshaft design only vibrates fore and aft along the axis of the wheels, not side to side like parallel twins, Buell could rubber-mount the engine flexibly in the frame, yet still use it as a fully stressed member. Controlling its lateral movement via four rose-jointed tie-rods, two of which resisted chassis deflection around an axis defined by the other two, the engine could only move in one plane – forwards and backwards (hence the later Uniplanar name).

With the all-enveloping bodywork, you couldn’t see the engine shaking on its rubber mounts, and I had very little sensation of it doing so even when revving the lazy engine as hard as it would go – pretty pointless with so much torque on offer, making the fact there were only four ratios in that slow-action gearbox less of an issue. The engine still wasn’t as smooth as a Ducati, but pretty close, and a great improvement on the standard XR1000.

One inexplicable carryover from the standard H-D was smooth plastic handlebar grips. With the very stiff Dell’Orto return springs (to combat the suction effect of the deep-breathing XR750 heads) I had cramp in my right hand after a few miles, and smooth gearshifting was difficult. It took some force to keep the throttle twisted wide open, and at a steady speed the residual engine vibes eventually made your hand slip off the totally smooth grip. Not good.

On the few bumps and thumps found in the Maryland countryside, the innovative rear suspension proved compliant, working progressively and smoothly without bottoming out or jarring. Buell’s offset monolever design had a specially made Works Performance monoshock mounted lengthways beneath the engine, working in traction rather than the conventional compression, with a remote gas reservoir and adjustment for spring preload only (you couldn’t alter the damping). But there was far more rear wheel travel than on a regular twin-shock Harley, albeit with a huge distance between the swingarm pivot and the gearbox sprocket of a whopping 150mm due to the layout of the H-D engine. That extra, more compliant suspension movement placed a heavy load on the drive chain.

Yet the Buell’s extremely short 1345mm wheelbase yielded fast, light and poised steering when combined with the sportsbike steering geometry. And considering the iron-barrelled engine alone weighed just on 90kg, the fully faired RR1000’s claimed dry weight, with all street equipment, of just 170kg (against 212kg for the naked XR1000 with the same engine) was a genuine achievement, underlining the minimalist character of Buell’s chassis design and the race-bred, lightweight nature of the hardware fitted.

The wheels and brakes were a good instance of this. The British-made 16-inch Dymag wheels, which Buell imported into the US, carried lightweight 310mm floating discs up front that Erik made himself from aluminium, then plasma-sprayed with stainless steel.

At the rear was a 220mm floating disc of the same material. Four-piston Lockheed Racing calipers were fitted up front – back then the benchmark of 500cc grand prix racing brake technology – while the tyres were the latest Pirelli MP-7R radials.

Strikingly liveried in ‘proper’ Harley colours of orange, black and white, the Buell’s all-enclosing bodywork was not to everyone’s taste, but was effective in reducing drag and protecting the rider from the elements. The very wide seat, its padding stuck down with Velcro, was comfortable by sportsbike standards, and even a taller rider like me found it easy to wrap around the six-gallon tank, made from Kevlar with an aircraft-type quickfiller.

The fairing, which on this first roadbike bearing the Buell name was still a prototype, actually fitted quite well and didn’t shake or rattle at all. It endowed the RR1000 with low drag, improving fuel consumption and, in tuned or racing form, allowing an impressive top speed. The front mudguard was designed to deflect cooling air towards the engine, smooth out turbulence around the wheel and brakes, and look, er, quite distinctive. Mission accomplished.

But it was how the Buell performed that really counted, and on that score it compared favourably with any European street racing design. Just like the innovative hub-centre Tesi prototype that Bimota had just started to develop, the Buell liked to be cornered on the power. If you backed off on the angle, the RR1000 would start to understeer noticeably, pushing the front end hard and demanding effort to pull it back in line. Yet if you powered through the corner with the engine driving reasonably hard, you’d be rewarded with positive, fluent and neutral handling that made it nothing like a Harley.

Middle America may not have been ready for something as extreme and avant garde as the Buell RR1000 Battle Twin. But it was Erik Buell’s creative achievement against the odds for which he deserved credit, together with his dedication and determination in producing it as the template for three decades of motorcycling innovation.