KTM’s mid-sized single-cylinder Duke is Austria’s ageless fun machine. For the past 22 years, the lightweight Duke has been attracting a rider who prefers motorcycling for its raw and frantic nature. The fact the original incarnation of the Duke was successful in spite of its left-hand kickstart only illustrates the type of rider it attracted.

With the single-cylinder fun came the inevitable single-cylinder thump, the teeth-chattering vibrations that are a rite of passage for single-cylinder roadbike ownership and KTM’s LC4-powered platform was no exception. It mattered little to owners, a small compromise for owning a bike bred from the gnarly racing roots of Supermoto.

Time moved on and KTM’s middleweight Duke began to settle down. After three major (and many minor) model upgrades through to the end of 2011, the 690 Duke moved away from the tall athletic motard stance and took on a slightly more sensible nakedbike persona. Now, 22 years after the 1994 620 Duke slid sideways onto our the streets, the search for sensibility has peaked and KTM has achieved what many thought impossible.

It has developed a single-cylinder roadbike which is virtually free of vibrations. Here’s how.

Captain Good Vibes

To understand how KTM managed to eliminate vibrations, first we need to understand why singles are so vibey in the first place. Because a single has only one power stroke for the crankshaft’s two revolutions, a single-cylinder engine requires a much heavier flywheel than a multi-cylinder engine. To counteract the large rotating masses of metal, an eccentric-weighted gear- or chain-driven shaft called a balancer shaft is thrown in the mix in a bid to bring it all back into check. Generally speaking, the more cylinders an engine has, the less vibrations it will produce because it has more power strokes per revolution which therefore reduces the severity of each piston’s throw.

Manufacturers tend to use rubber mounting to ease the vibrations. Much like the rubber feet designed to go under washing machines to reduce the severity of a high-rpm spin cycle, adding rubber to the mounting points of the engine, handlebars, footpegs, and anything else that may absorb the momentum before it reaches the rider’s extremities has been a cost-effective and relatively efficient way to deal with vibrations.

How’d KTM do it?

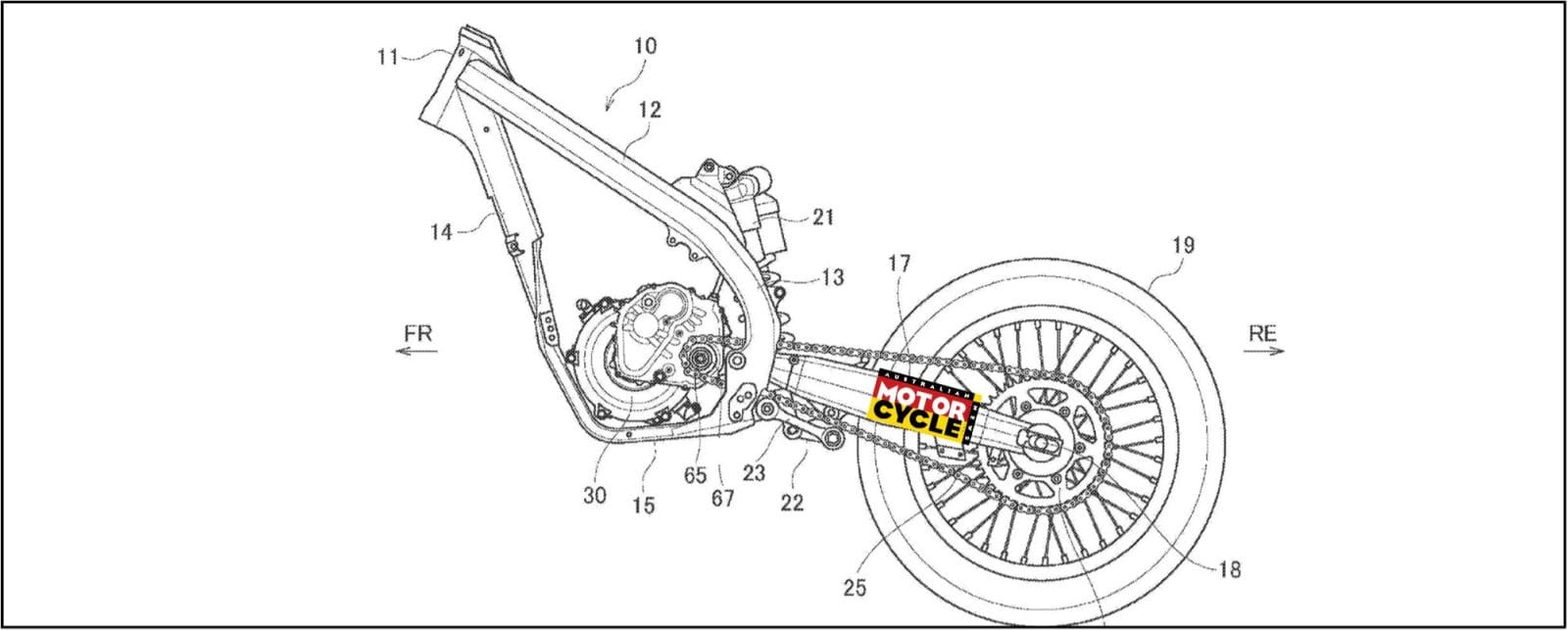

KTM has essentially smoothed out vibes from the single-cylinder engine by modifying the head to make the camshaft act like a secondary balancer shaft. This, in itself, isn’t revolutionary as many engines employ a secondary balancer shaft. But it’s how KTM has integrated it to reduce the mass of moving parts which is the tricky bit.

Mimicking the configuration of a DOHC cylinder head, the inlet valves are now driven directly off the cams, while the the exhaust valves are still actuated by rockers. By adding an eccentric weight to the end of the camshaft mounted at the very top of the engine, it perfectly complements the rotating mass of the flywheel and balance shaft directly beneath it and settles the whole single-throw-show down to levels of smoothness not yet experienced on a single-cylinder roady.

“We did not want to increase the height of the engine, and the cylinder head was a good location in the end because there is force from the lower balancer shaft around the crankshaft … and we’re working against it with the smaller shaft,” explains KTM’s four-stroke engine designer Sebastian Faistauer. “It means a compact design and one that was only possible thanks to the compact valve train.”

It also means the days of the frantic short-distance fun demanded by the early Duke’s comfort levels are over, too. A smoother ride atop a more ergonomically comfortable machine gives the latest mid-sized Duke and its fun-loving owners true all-day aspirations.

What else?

The considerable reduction of vibrations is an excellent outcome of the LC4’s significant development, but that’s not the only thing the latest incarnation achieved.

The bore has been increased by 3mm and the stroke shortened by 4.5mm for more-or-less the same capacity, which made space for larger intake valves. It also made for a shorter-stroke engine which is able to rev 1000rpm higher than the already rev-happy single which preceded it.

The broader range has seen power output increased by seven percent up to 54kW (73hp) and torque is boosted by six percent to 74Nm.

Like many updated machines for 2016, the latest 690 Duke complies with the Euro 4 emission restrictions which will be enforced from 2017, fuel consumption has been improved as a by product and all new internal hardware (piston, con-rod, crankshaft and diamond-like coatings smeared here and there) results in increased reliability and durability.

Good news for an engine powering a bike you’ll be able to ride further for longer.

By Kel Buckley