Les Graham was part of that special breed of racer whose careers were interrupted by the Second World War. That was quite a life – racing on lethal street circuits in the 1930s, fighting and surviving a war, then happily staring death in the face all over again.

There were thousands of racers – on both sides – who lived this extraordinary life, but only one of them became a 500cc World Champion. Germany’s pre-war TT winners, Georg Meier and Ewald Kluge, both continued racing after the war, but they were on the way down, not on the way up. Graham, however, got the chances that he should have had before the war and went on to win the first 500cc world title in 1949.

War and racing – in those dangerous days of unforgiving street circuits – had some things in common. Certainly, motorsport is the truest form of George Orwell’s declaration that “sport is war minus the shooting”. Not only is there great risk of death, but also the exponent’s chances of survival and victory depend on an ability to work with machines.

Graham could certainly work with machines. On a motorcycle he was renowned for his talent for effortlessly riding on the very edge – perhaps a consequence of his varied upbringing in grass track, sand racing and road racing. He was also an excellent mechanic who built engines for OK Supreme, so he understood how things worked.

Both these factors no doubt played a vital part in the wartime events that won him the Distinguished Flying Cross medal. Flight Lieutenant Graham flew RAF Lancasters in attacks on Germany and German-occupied France, bombing everything from Luftwaffe fighter and V-1 bases to Wehrmacht tank and artillery positions and synthetic fuel-manufacturing plants.

The losses suffered by RAF bomber crews were horrific: 45 percent died in action, the worst in any branch of the British military in either the First or Second World War. During Graham’s first series of 30 sorties, his 166 Squadron lost 182 men, more than half its original number.

Unlike the RAF’s glamorous fighter pilots, who were the knights of the sky in their Spitfires and Hurricanes, bomber crews were essentially long-distance truck drivers delivering a lethal cargo, waiting to be jumped by bandits or pummelled by flak. Lumbering along at 402km/h, they were sitting ducks for the Luftwaffe’s Messerschmitt ME109s which cut through the air at 563km/h.

Graham was at the controls during a raid on U-boat submarine pens in August 1944 when a Lancaster flying immediately below blew up. The force of the blast flipped Graham’s plane onto its back, dumping him out of the pilot’s seat.

“All of a sudden, we were upside down and hurtling towards the ground,” recalls Graham’s navigator, Bill Bissonnette, in Matthew Freudenberg’s biography Les Graham: A Life in Racing. “As we flipped over, Les spilled into the centre of the craft and I thought our end had come. Les was scrambling about, draped over the throttles and trying to reach the stick. Finally, he got his left hand on it and managed somehow to pull us out of it.” This deed won him the DFC.

Three days after that brush with death, Graham was instructed to orbit the target area and photograph the damage following a raid on a night-fighter base. Inevitably, his plane was peppered with flak and lost a wheel, so landing was going to be a problem. Bissonnette again recalls: “Somehow, Les managed to drop the port wing so it barely cleared the ground and landed the Lanc like a bicycle on the port wheel and the tail wheel.”

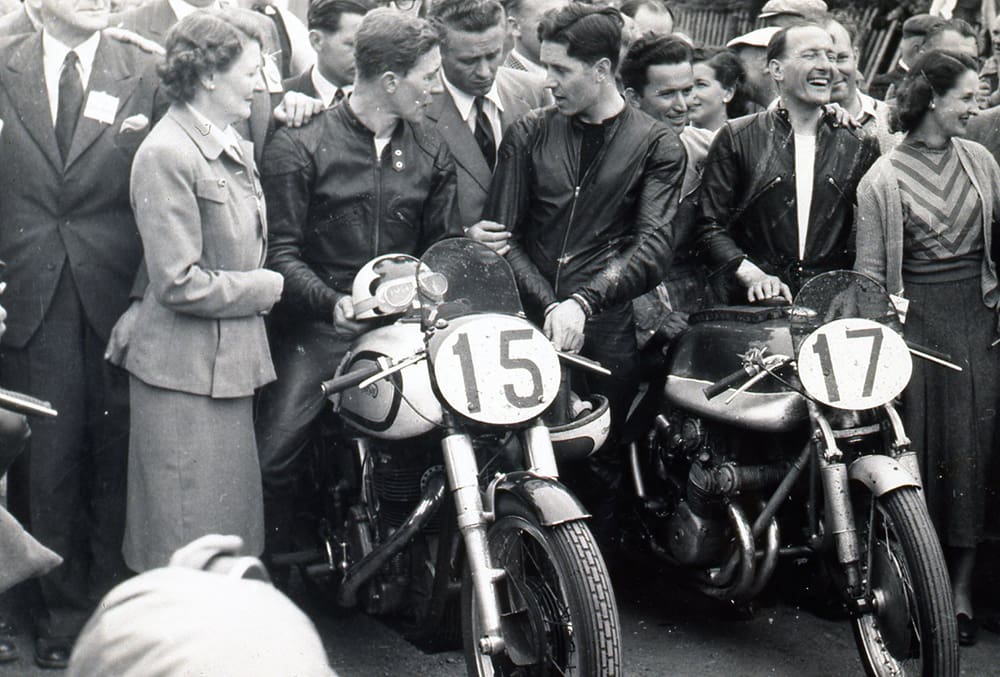

Graham was demobbed 11 months after VJ day – August 15, 1945 – and had no doubt about what he was going to do next. Machinery, however, was a problem. Before the war he raced for OK Supreme, having started out on a Dot JAP in 1928, and was more often than not dogged by bad luck. After the war he had to make do with a borrowed Norton, until his prayers were answered when newly appointed AJS race chief Jock West came looking for him. Before the war, West rode supercharged twins for the Nazi-backed BMW factory. At the Donington Easter meeting of 1939, he spotted Graham riding his OK Supreme speedway-style through Redgate corner. There and then he made a mental note to help the youngster get better machinery.

AJS had big plans after the war. While the factory worked on military contracts during the conflict, its engineers looked forward to better times by designing a supercharged 500 parallel twin. Legend has it that Joe Craig designed the engine after he quit Norton, who wouldn’t let him build a four. There was only one problem: in June 1946 the FIM banned blowers. Thus the E90 twin – with unusual spiky cooling fins that earned it the nickname Porcupine – was forever compromised and never became the machine it should have been.

Nonetheless, by 1948, the bike was running well enough to allow Graham to lead the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa, until a sparkplug failed. And when the FIM announced the creation of the first World Championship in February 1949, the AJS team had good reason to believe that they stood a chance against the Norton singles, Moto Guzzi V-twins

and Gilera fours.

June’s Isle of Man TT – the first World Championship motorcycle race – confirmed their hopes. Graham led by more than a minute as he swept through the final lap, waved on by fans. Then at Cronk-ny-Mona, a mere 3.2km from the finish, his Porcupine died – a magneto shaft had sheared. Graham reacted with equanimity, as he always did when luck turned against him. No doubt wartime adversities made such setbacks easier to handle.

Reliability was a serious problem, often due to the failure of low-quality proprietary components, but the penny-pinching AJS owners did nothing about it. They wouldn’t even let Graham and his teammates replace the hopeless ‘Candlestick’ rear shocks with something they knew would work. This infuriating blinkered management attitude would become typical of the British industry.

Graham made up for his TT disappointment with wins at Berne in Switzerland and at the Ulster. With only the Monza season finale to go, he had a real chance of taking the title ahead of his main rival, Gilera’s Nello Pagani. The only question was how the AJS would cope against the Gilera at super-fast Monza. Norton was so certain of humiliation at the fastest track of them all that the team didn’t even bother turning up.

In fact, the British twin had very nearly as much top speed as the Italian four – along the 11.3km straight at the Ulster the AJS was just 1.6km/h slower than the 193km/h Gilera. The Monza race was a classic slipstreaming brawl, with Graham fighting back and forth with Gilera’s three riders: Pagani, Arciso Artesiani and crash-happy Carlo Bandirola, nicknamed Bouncing Bandi. In the closing stages, Bandirola lived up to his name, trying a ridiculous move on Graham. He crashed and took the Brit with him. Meanwhile, Pagani romped home to win.

So who was crowned World Champion? Pagani had scored nine more points than Graham, but FIM rules allowed riders to drop their three worst scores from the six races, so Graham took the title by just one point. The Merseysider still ranks as the oldest winner of the class of kings. He was within days of his 38th birthday when he was crowned, though this wasn’t considered old at the time because many of his rivals had also been racing before the war.

Graham’s name may have been cast in history as the first premier-class world champ, but he had a miserable title defence. Once again, luck and the AJS management were against him. By the end of 1950, he had had enough and accepted an offer from Count Domenico Agusta.

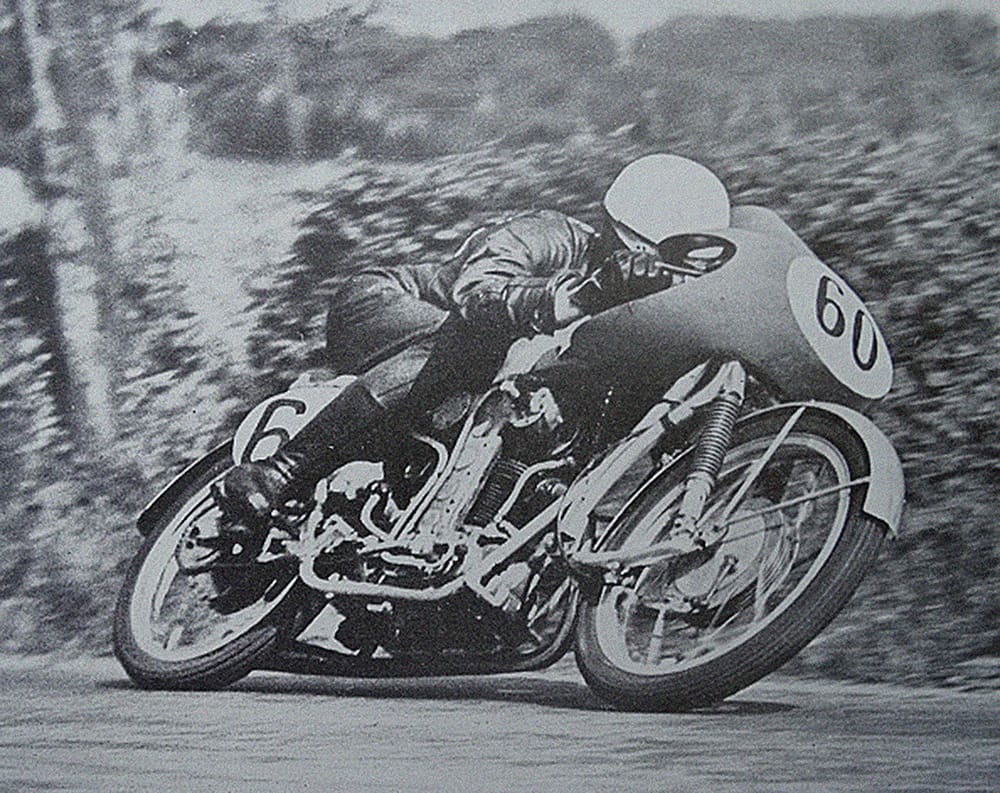

At this time, MV was not the dominant racing force it later became. The factory’s first 500 only made its debut at Spa in 1950 and the following year still featured shaft drive and torsion-bar suspension. The bike handled atrociously and was so fragile that Graham failed to achieve a single finish in the eight grands prix of 1951. It was here that his technical knowhow really came in handy. Although the Count was a control freak who insisted on being in charge of development, he soon realised Graham’s knowledge and intelligence offered a better way forward. The pair became great friends, the Graham family eventually setting up home in the Count’s holiday villa near Lake Lugano, which became known as Casa Gram.

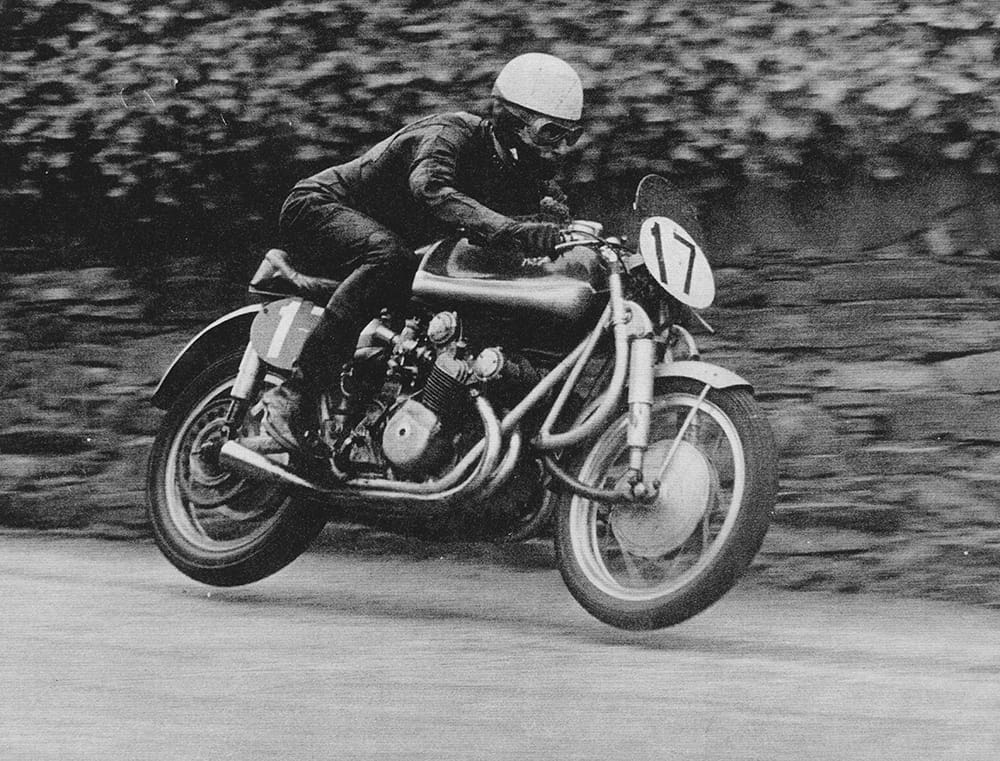

Given a free hand with development, Graham improved the MV’s engine and chassis step by step, putting almost two decades of racing experience into effect. Cylinder bore was reduced to cure piston failures caused by increasing power and heat, chain final drive and smaller wheels were introduced, and a new tubular frame was designed. Graham’s dirtbike background gave him a preference for longer travel suspension, which he found worked well with hydraulic rear shocks and Earles front forks, designed by former Velocette engineer Ernie Earles.

Finally, by the end of 1952, the MV was good enough to beat the dominant Gileras. Graham beat world champ Umberto Masetti at Barcelona and most importantly at Monza, where Gilera was so incensed it put in a protest, claiming MV was cheating with an oversize engine.

The 1953 season promised a straight head-to-head between Graham and Gilera’s new signing, Geoff Duke. It never happened. The day after claiming a long-awaited first TT victory aboard MV’s 125 single, Graham crashed the 500 at the bottom of Bray Hill. He died instantly. The cause of the crash remains unknown, despite various theories, ranging from a problem with the Earles forks to a broken rear-wheel spindle, to a bunch of backmarkers putting him off line.

Engineer Arturo Magni, who worked at MV from 1950 to ’76, rated Graham the best rider the factory ever had – quite a statement considering John Surtees, Gary Hocking, Mike Hailwood, Giacomo Agostini and Phil Read were also employed there. “Les was very technical and a fantastic rider – he was the greatest of all MV’s riders,” said Magni.