Harley Davidson v-seris wasn’t shy about promoting its V-series 74ci (1210cc) Big Twin flathead: “Brilliant in design and engineering, brilliant in colours and chrome plating, brilliant in speed and performance – the new Big Twin is setting a new and faster pace in motorcycle history,” the PR blurb gushed. “Here is a mount that has everything you want or expect in a modern motorcycle – with advantages that no other motorcycle can offer, regardless of price.”

And then there was the sidecar: “The safest, the most convenient and easiest-riding sidecar outfit on the market!”

No doubt about it, a Big Twin combination sounded like it was just the job for transporting a delicate cargo quickly and discreetly across the state of Pennsylvania during the Prohibition era. The manufacture, transportation and sale of alcoholic drinks were banned in America on 16 January, 1919, but it takes more than the law to stand between a drinker and his poison.

Rum was smuggled from the Bahamas to Florida; Canadian whiskey and English gin were loaded onto fast ships and brought into the north of the country. Racketeers and gangsters flourished, not only because there was easy money to be made, but because Prohibition wasn’t popular with everyone.

An army of little-league bootleggers served drinking dens and private houses around the country. And that’s how this Harley outfit became known as the Rum Runner.

“Every old-timer in town knew the story behind this Harley rig,” Pennsylvanian local Jack Talley explains.

“The country was in the depths of the Great Depression when Billy Smith bought it in 1932 and started smuggling rum to earn a few extra dollars.”

Introduced in 1929 for the 1930 season, the Harley Davidson V-series was designed to go head-to-head with the Indian Chief. Harley desperately needed a replacement for the outdated inlet-over-exhaust J-series Big Twins. With a single camshaft operating all four valves, the stock J produced an asthmatic 13kW (18hp).

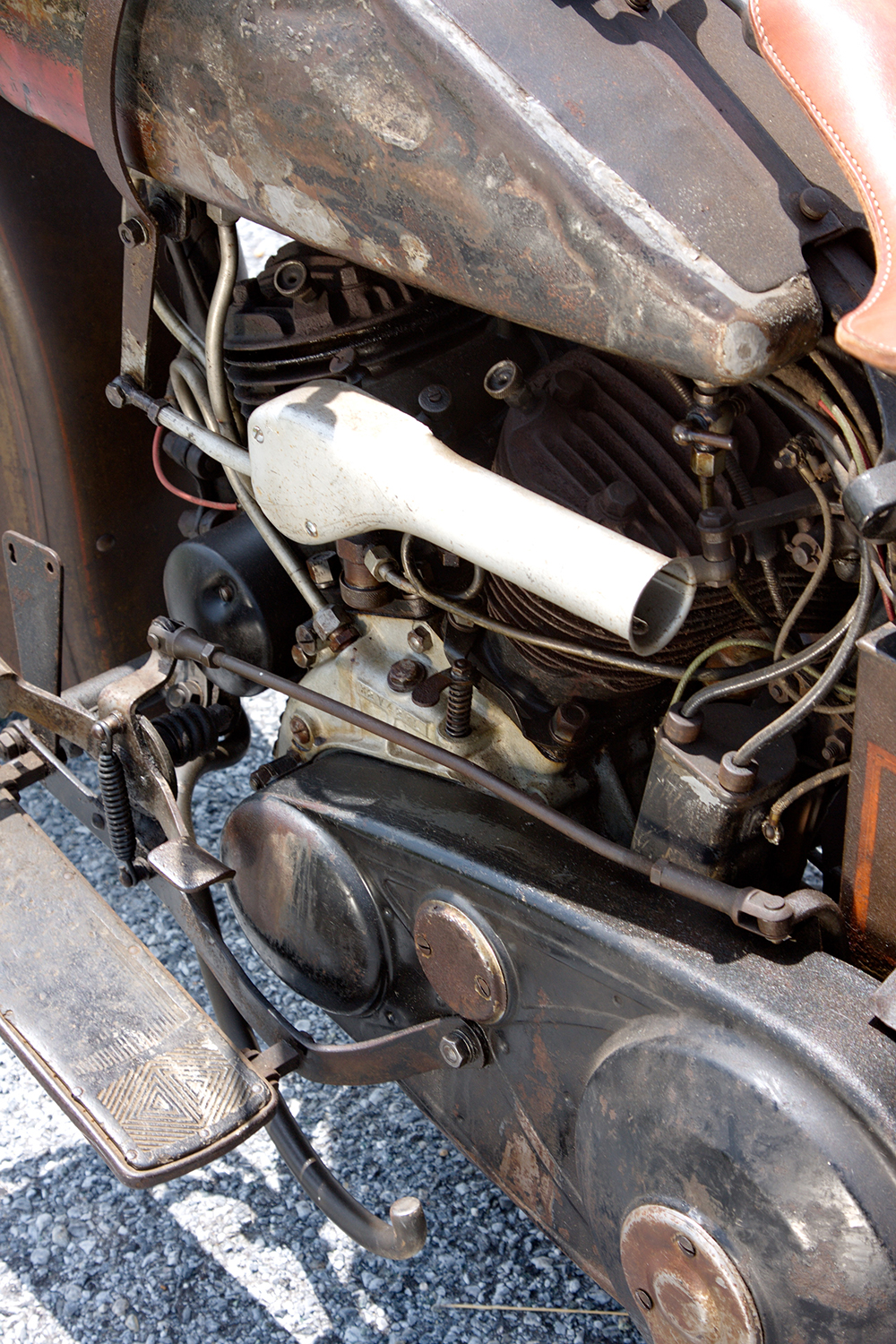

The V-series 74 cubic-inch (1210cc) engine was the big brother to the Harley 45 introduced the previous year. Four dedicated cam gears – one for each valve – and detachable squish cylinder heads based on a design by Englishman Harry Ricardo hinted at the performance available.

Engine lubrication was taken care of by a throttle-controlled mechanical pump that also delivered oil to the duplex primary chain – from where it would leak out of the pressed-steel chain case and onto the road. When Indian introduced a circulating dry-sump lubrication system, Harley cheekily boasted in adverts that its vintage total-loss system meant only clean oil was used in its machines.

A generator supplied enough power for the twin-coil ignition, plus the Klaxon horn and lights. The 1930 V-models used two small dual bullet headlamps as on the J-series, but these were replaced with a single large John Brown Motolamp in 1931. Other options included a steering damper, a sidestand, windscreen, an 80mph (130km/h) speedometer, or – for the truly optimistic – a 100mph (160km/h) Corbin instrument. By the time Billy Smith took delivery of his Model V and sidecar – with the optional three-speed (plus reverse gear) – the bike featured redesigned cylinders which

gave improved airflow for better cooling between the exhaust ports and the barrels, and an even stronger fork.

With standard medium-compression 4:1 alloy pistons, he had a reliable 20kW (28hp) to haul those bottles of illegal rum, and a lighter mechanical oil pump spring for snappier throttle action.

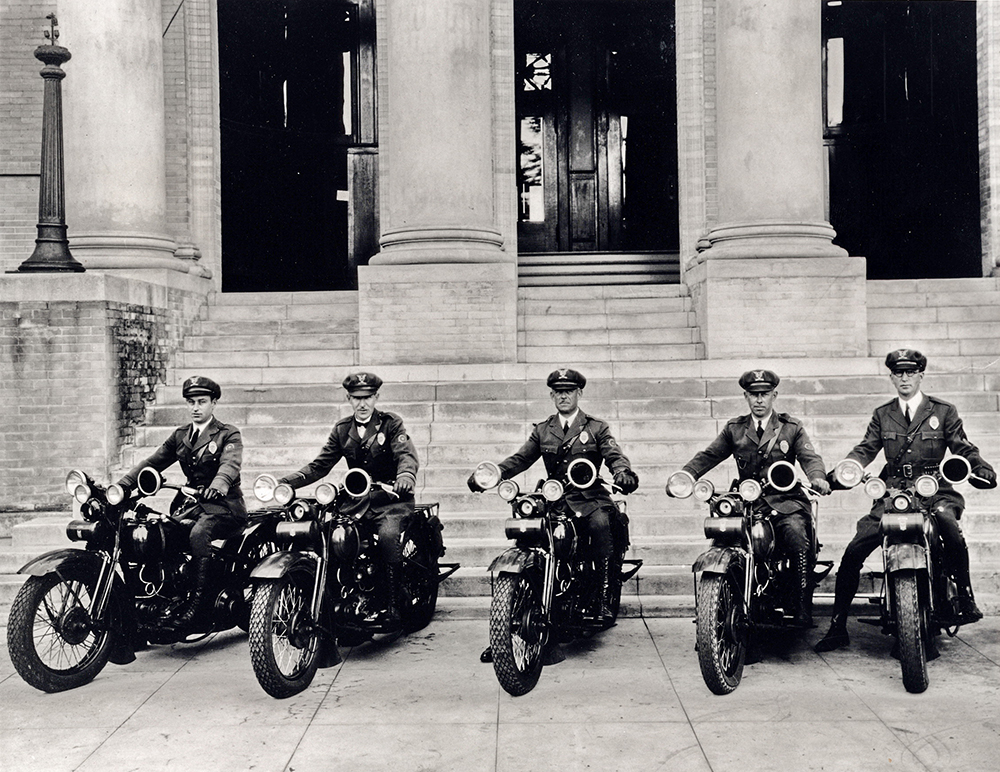

But he wasn’t the only threat to law and order, as Harley’s police motorcycle brochure pointed out: “A few short years ago, machine-gun bandits, kidnappers, youthful hold-up men, racketeers and gangsters were scarcely heard of, but now they have become bywords in every community throughout the land.”

Naturally, Milwaukee had the answer: “To whip this group into line there is an effective solution – virile young officers mounted on Harley-Davidson motorcycles.”

In 1932, more than 3000 police forces were using Harleys. The lucky ones got the latest VL, with 4.5:1 compression pistons, an extra two horses and a top speed of 85mph (140km/h) compared to the 80mph (130km/h) of the V. Those gun-toting motorcycle cops were riding solos, so Billy Smith had no chance of outrunning them.

“Nothing will strike more terror into the heart of a law violator than the scream of a police motorcycle siren,” added Harley’s scribe. “He realises flight is futile for he knows too well that the motorcycle officer can flash through traffic or fly over the highway and quickly overtake him. And few lawbreakers will take a chance against motorcycle officers who are physically hardened and mentally quick and sharp from their service in the open air.”

But Billy Smith was as sharp as any motorcycle cop. He knew he’d get pulled over, so he stashed the bottles of rum in the nose of the sidecar and covered them with a tarpaulin before topping up the passenger compartment with sacks of coal.

“In those days plenty of people hauled coal for their kitchen stoves, so it didn’t look suspicious,” Jack explains. “Our Pennsylvania coal was ground to a one-inch (25mm) sieve size so that we could use it in cooking stoves.

“It was bituminous coal, so it contained a lot of tar, and any cop who poked around those sacks would get his clothes pretty cruddy!”

Of course, no cop wanted to get his hands dirty – so although Billy was often stopped, his stash of rum was never discovered. Such was the demand for his contraband that the sidecar held a full load of coal from the day it left the showroom until the end of Prohibition in December 1933.

Then he saw the 1934 Harley brochure: “They’re newer than new, hotter than hot, faster than fast, and neater than neat.

“In fact, brother, they’re honeys! These new 1934 model Harley-Davidsons make previous models, as good as they were, look out of date, and no foolin’. These 1934 dream ships with their ultra-modern styling will make your old heart go pit-a-pat when you check them over. Look at the new fenders. Ain’t that sumpin!

“Streamlining adapted to a motorcycle at its very best. Air-flo design is what we call it, and it matches up in style with the dynamite and wallop packed in the 1934 VLD motors.

“When you pour in that throttle, they cut loose and start producing real horses, actually 36hp (26kW) at 4600rpm, and we don’t have to tell you that this means miles per hour and lots of ’em.

“When this husky baby starts drinking in gasoline through that Y-shaped, no resistance intake manifold, things start to happen and your speedometer needle begins to move like the second hand on a watch.”

Billy didn’t have the cash to trade up, but $20 saved from rum running was enough for those Air-flo fenders and a trim tail-light. He got the local Harley dealer to fit them to his faithful Model V. Now, if he screwed up his eyes he could almost believe that he had a new Harley and it would take an expert to tell him otherwise.

He rode the Harley Davidson V-series for another eight years before he parked it in his barn, sidecar still full of coal dust, and there it lay until Charlie LaTomaine bought it in 1960.

“I used to buy old Harley parts from Charlie,” Jack says. “When I visited his place one day in 1984 – it was little more than a rundown trailer house – he let me look in his barn and I saw the Big Twin hidden away in a far corner.

“The paint was badly faded and it was covered with decades of oil and dirt. There was no speedometer fitted, but the wear on the floorboards, handgrips and foot controls indicated that the mileage was quite low.

Hanging nearby on the wall was the sidecar frame, while the body sat overhead in the rafters. I asked Charlie where he got it, and he told me about Billy Smith.”

Annual pilgrimages to see Charlie followed and each time he learned a little more about Billy and the Rum Runner.

Then, in 1999, Charlie told Jack that his time was nearly up and he was ready to sell the rig.

“I know how much you want it, so I’m giving you first crack at her,” Charlie said. “Just bring me (US) $14,500 and she’s yours.”

Jack could hardly believe his ears, but there was a problem. He and his wife Dawn had just bought a house and could only come up with $7000.

“I went to Charlie and began to, well, basically to beg,” recalls Jack. “Charlie was obviously not long for this world and he really wanted the machine to have a proper home, so he settled on $7500.”

Charlie didn’t last much longer but Jack, the third owner, wasn’t going to let the Harley-Davidson Rum Runner languish in his barn.

He cleaned it to bring the original finish to the best condition possible, replaced the carburettor float and battery and flushed out the crankcase with kerosene before injecting fresh oil with the hand pump.

“The engine started right up,” Jacks says.

“It sounded great and felt nice and fresh after such a long rest.

“We were surprised to see that the floor of the sidecar hadn’t rotted out – friends told me that they all do – but coal tar had preserved it.

It seems that there was a hidden benefit from rum running!”

Last year Jack rode the Rum Runner on a camping trip down the Blue Ridge Parkway. This is an astonishing ride on an immaculate road built by the US Army Corps of Engineers that follows the high ridge of the Appalachians for over 800km.

There are no crossroads, no traffic lights, and no McDonald’s. When he got back to his hometown of Kennet Square in Pennsylvania, he met the son and grandson of Billy Smith.

“Did you take any rum with you?” joked Billy Jr. “No,” replied Jack. “I loaded up the sidecar with Budweiser. But I didn’t cover it with coal!”

Jack made an annual pilgrimage to see Charlie and each time he learnt a little more about Billy and the Rum Runner. Then, in 1999, Charlie told Jack that his time to die was near and he was ready to sell the rig. “I know how much you want it, so I’m giving you first crack at her,” said Charlie. “Just bring me $14,500 and she’s yours.” Jack could hardly believe his ears, but there was a problem. He and his wife Dawn had just bought their house and there just wasn’t much money left. He could scrape together only $7,000. “I went to Charlie and began to, well, basically to beg,” recalls Jack. “Charlie was obviously not long for this world and he really wanted the machine to have a proper home so he settled on $7,500 which included my next two pay cheques!”

Charlie didn’t last much longer but Jack, the third owner, wasn’t going to let the Rum Runner languish in his barn. He cleaned it to bring the original finish to the best condition possible, replaced the carburettor float and battery, and flushed out the crankcase with kerosene before injecting fresh oil with the hand pump. “The engine started right up. It sounded great and felt nice and fresh after such a long rest,” says Jack. “We were surprised to see that the floor of the sidecar hadn’t rotted out – friends told me that they all do – but coal tar had preserved it. It seems that there was a hidden benefit from rum running!”

Last year Jack rode the Harley Davidson V-series Rum Runner on a camping trip down the Blue Ridge Parkway. This is an astonishing ride on an immaculate road built by the US Army Corps of Engineers that follows the high ridge of the Appalachians for over 500 miles. There are no crossroads, no traffic lights, and no McDonald’s. When he got back to Kennet Square he met the son and grandson of Billy Smith. “Did you take any rum with you?” joked Billy Jr. “No,” replied Jack. “I loaded up the sidecar with Budweiser. But I didn’t cover it with coal!”

“I know how much you want it, so I’m giving you first crack at her,” Charlie said. “Just bring me $14,500 and she’s yours.”

Jack could hardly believe his ears – but there was a problem. He and his wife, Dawn, had just bought their house and there wasn’t much money left – they scraped together $7000.

“I went to Charlie and began to, well, basically to beg,” Jack recalls. “He was obviously not long for this world and really wanted the machine to have a proper home so we settled on $7,500, which included my next two pay cheques!”

Charlie didn’t last much longer but Jack, now the third owner, wasn’t going to let the Rum Runner languish any longer. He cleaned it up to bring the original finish to the best condition possible, replaced the carburettor float and battery, and flushed out the crankcase with kerosene before injecting fresh oil with the hand pump.

“The engine started right up. It sounded great and felt nice and fresh after such a long rest,” he says. “We were surprised to see that the floor of the sidecar hadn’t rotted out – friends told me that they all do – but coal tar had preserved it. It seems there was a hidden benefit from rum running!”

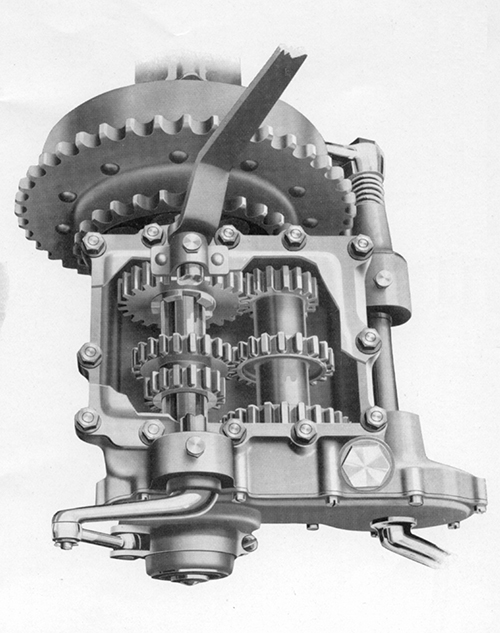

Three-Speed gearbox

The three-speed crash gearbox was carried over from the J-series and came with hand-shift, a locking device to stop the gears jumping out of mesh, and a dry clutch operated by a rocking pedal on the left. There was also a gearbox with reverse for sidecar work, but this option was expensive and there were few takers.

The first Harley V-twin of 1909 was a single speeder with a leather belt drive from a pulley on the crankshaft to the rear wheel. Late in 1913 a two-speed epicyclic gear was mounted in the rear hub (the same principle as a bicycle gear), but it wasn’t much of a success.

Harley riders got their first gearbox two years later with the Model J Silent Grey Fellow. This three-speed crash gearbox came with a kickstarter, a hand-shift on the left side of the tank, a locking device to stop the gears jumping out of mesh, and a dry clutch operated by a rocking foot pedal.

It was this gearbox that was used in the Harley Davidson V-series of big side-valves. There would also be a gearbox with reverse for sidecar work, but this option was expensive and there were few takers. It wasn’t until 1935 that Harley finally got around to offering a constant mesh gearbox. With four cams and Ricardo heads, the V-series produced close to 22kW (30hp), but road performance was hampered by excess weight, much of it down to the new frame and leading-link fork. It might have been stronger than the J-type, but the frame was also 25 percent heavier.

Story & photography Phillip Tooth