When Mike Hailwood won the Formula One TT on 7 June 1978, his victory didn’t just make headlines in the motorcycling press and sport pages of newspapers. It became a worldwide story of one of sport’s greatest comebacks. And it remains so, 40 years later.

At 38, Hailwood hadn’t raced at the TT for 11 years. And his return was a spur-of-the-moment decision, not some carefully crafted career strategy. It was simply based on his enjoyment of a couple of race meetings in Australia with a couple of young Aussies as his sidekicks.

Now Hailwood would take this casual attitude to the world’s toughest race track. The nine-time World Champion rose to the occasion. He not only added another TT victory to the dozen he’d won in the 1960s, he also set a new lap record on his factory-supported Ducati.

Hailwood’s six-lap thriller even rivalled his previous TT victory in 1967. Back then Hailwood, on a Honda, beat Giacomo Agostini and his MV with a Senior-class lap record that would stand for eight years. This time he’d beaten Honda and its star rider Phil Read while setting another lap record.

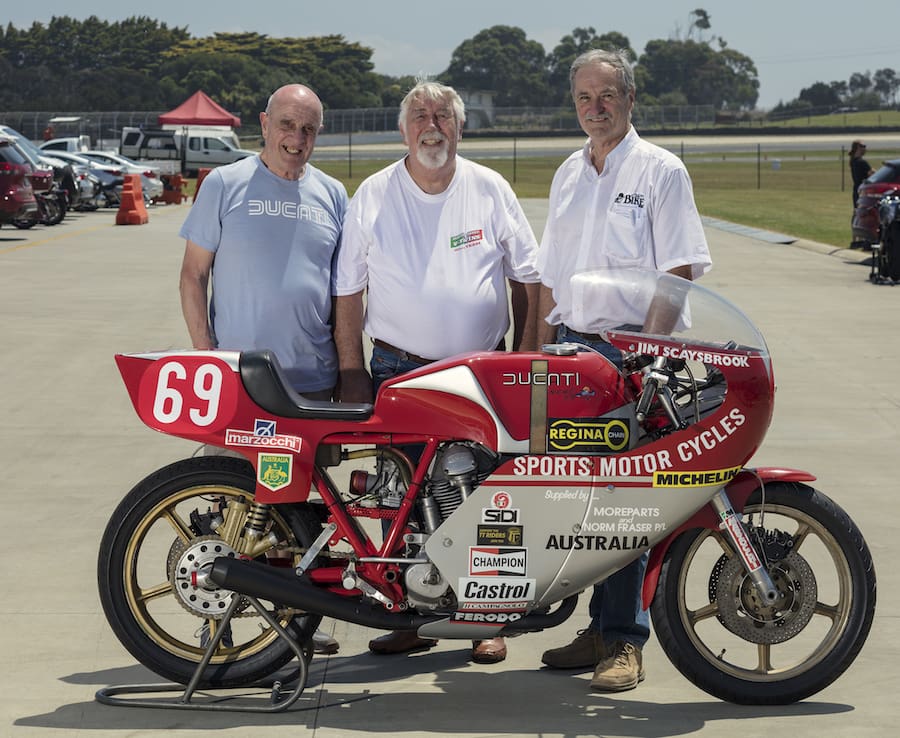

AMCN’s 2018 International Island Classic was the scene for a mini-reunion of some unheralded but key players in one of the most unlikely comebacks in motorcycle racing.

Hailwood’s main technician at the 1978 Isle of Man TT, Pat Slinn, met up with Neil Cummins, Mike’s mechanic in Australia in the lead-up to the TT, and Mike’s teammate Jim Scaysbrook.

Cummins spannered for Scaysbrook at the 1978 TT, his Island debut, on a sister Ducati to Hailwood’s. They posed with Scaysbrook’s Ducati while the memories flooded back – it might be 40 years ago, but it seems just like yesterday for these men.

“The whole thing is still fresh in my mind,” said Cummins, who had ridden a rollercoaster of emotions watching Scaysbrook head off on his first TT race.

Asked what their one over-riding memory of that event was, Slinn and Cummins answered in unison: “Reliability!”

Cummins explained that Scaysbrook’s engine had done more than 1500km of racing without any major work by the time it got back to Australia. Hailwood’s more souped-up engine failed only as it crossed the line (it broke a bevel drive gear on deceleration), having done its job perfectly.

“Everyone talks about the engine, but the drive chain was so stretched it was ready to jump the sprockets,” Slinn recalled.

Looking back four decades, it might seem a strange choice to challenge the might of the Honda factory racing team with a road-derived Ducati, but a check of the history books brings that decision into focus.

In 1977, British Ducati rider Roger Nicholls had controversially lost a certain victory over Read’s factory Honda in the first-ever Formula One TT race. Over preceding years, Ducati had built up a worldwide reputation in endurance and production racing, starting with its fairytale win at the 1972 Imola 200. At least half a dozen Ducatis were entered for 1978 and Hailwood had built experience on the brand in Australia, one of Ducati’s leading marketplaces. He had teamed with Scaysbrook in long-distance events, with Cummins wielding the spanners.

The dream return began at Amaroo Park early in 1977 when Hailwood jumped on a Manx Norton at a historic meeting.

“Owen Delaney (a Sydney radio announcer and petrolhead) had been working in Auckland and became friends with Mike,” Scaysbrook said. “Basically, after a lifetime of racing hedonism on two and four wheels, Mike was bored shitless selling outboard motors and boats at a big marine dealership in New Zealand. So Delaney pulled a few strings and next thing Mike’s racing at a similar meeting at Bathurst.”

Scaysbrook was the man to beat at both meetings and the pair struck up a friendship. Delaney then organised a deal to get Hailwood and Scaysbrook teamed up on a Ducati for the Castrol Six Hour at Amaroo Park in October.

As the date approached, Hailwood visited the British Grand Prix at Silverstone, where he famously sat on one of Steve Wynne’s Ducatis, entered in a support race, and said: “This is the kind of old-fashioned bike I understand … wouldn’t mind doing another TT on this.”

So the wheels started turning back in Europe. Wynne’s Sports Motorcycles dealership and Pat Slinn, service and technical manager of UK importers Coburn and Hughes, set about sourcing the required machinery.

Back in Australia, Hailwood got up to speed with Scaysbrook. They were an unlikely pair. Hailwood had a bung foot from an F1 car accident and must have harboured doubts about his ability to ride as hard as the new generation. Scaysbrook was a newcomer to tarmac competition; his racing career had centred on off-road events and he had been the first Australian to compete in the AMA motocross series.

But the results speak for themselves. With limited preparation, they finished sixth outright and second in the 750cc class in the Six Hour.

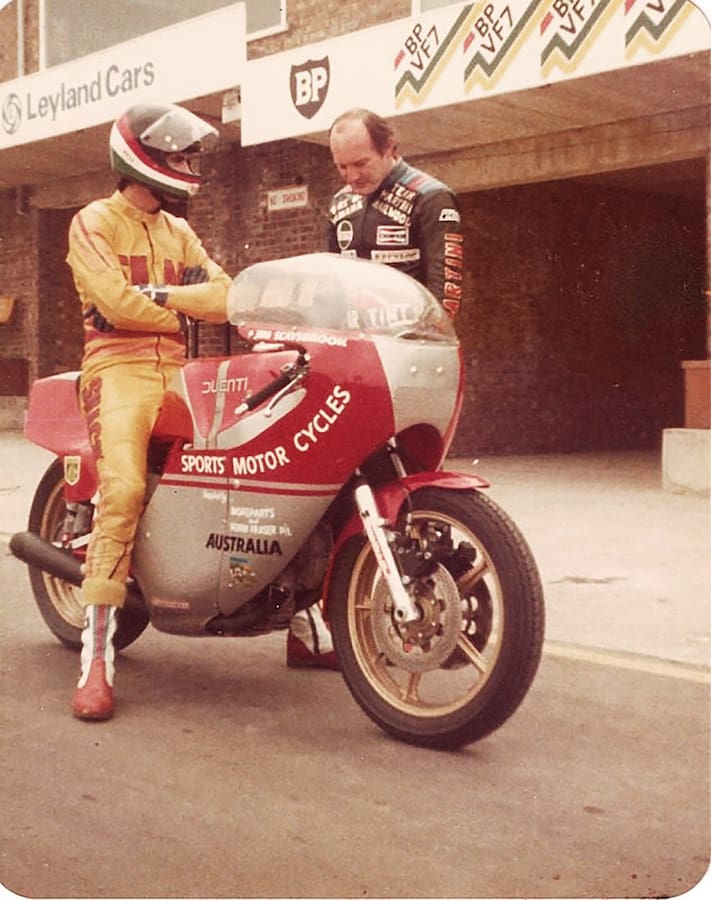

The next race was the 1978 Easter spectacular at Bathurst, Australia’s major road-racing event. While Scaysbrook took the Ducati to a class win and lap record, Hailwood raced a Yamaha TZ750 to a top-10 finish in the Unlimited class. This was good experience for the ex-pat Pom, as by now his TT return had ballooned into Martini sponsorship of Yamahas in three other races.

The trio then travelled to Adelaide for the Three Hour race with the by-now well-worn Ducati. Scaysbrook crashed in qualifying, requiring an all-night rebuild, but they finished ninth overall, defying handling and fuelling issues.

So the scene was set for Mike’s highly anticipated TT return, with Scaysbrook and Cummins planning to make their debut either with the old 750 or a new standard 900SS.

“Mike said to me: ‘Come along and I’ll give you a few tips’,” Scaysbrook recalls. “Then we found out that Ducati was making four or five of what I would call a TT860.

“Frasers (the Australian Ducati importer) and Moreparts (owner/sponsor of the Hailwood-Scaysbrook 750) put in an order for one, while Sports Motorcycles offered workshop space.”

And so the little team of rider Scaysbrook, young wife Sue and mechanic Cummins jetted off into the unknown.

“It very nearly didn’t happen, as our bike got caught up in the Genoa shipping strike,” Scaysbrook said. “By the time it had arrived

we’d missed the first scheduled test day at Oulton Park.”

Cummins will never forget first seeing the factory-prepared racer.

“It was a thing of beauty and I could have sat there and stared at it for hours,” he said.

What he was referring to was a beautiful, lightweight frame, based on the standard model but modified for racing. The engine was one of just 20 made for endurance and Formula One racing. It had sand-cast crankcases with strengthening ribs, a stronger bottom end with large-diameter crankpin, a spin-on external oil filter, close-ratio gearbox, air-cooled dry clutch, and many other improvements.

This was the ultimate version of the bevel-twin desmodromic design conceived almost 10 years earlier. And fewer than six complete bikes were being built to this specification.

Hailwood’s racer came with spare engines and some tweaks for the maestro, while the bikes for Sports Motorcycle’s regular rider, Roger Nicholls, and Scaysbrook were ‘as delivered’ from the factory.

“It was my first time overseas so everything was new to me,” Cummins recalls. “We’d brought no spares from Australia and I only had a few basic hand tools. Jim managed to buy an old Michelin endurance-spec treaded front tyre, but we ran that rear slick for as many kilometres as the engine (more than 1500km)!”

Scaysbrook has another take on it. “That rear slick was so hard you couldn’t wear it out,” he said.

Like Hailwood’s bike, the Scaysbrook Ducati had incredibly steeply raked clip-on handlebars. These combined with a rangy riding position to encourage maximum tuck-in at speed.

Compared to its Japanese rivals, many of which had aftermarket frames, the Ducati had a low overall height and looked long and lean. It was built for speed.

Seasons of European endurance racing had resolved many problems, such as the front cylinder’s exhaust header grounding out.

This was one of the best production-based racers you could buy, but the factory still preferred you ran points ignition rather than one of the new aftermarket electronic systems.

After Cummins prepared the bike and Scaysbrook had a brief gallop around the Donington circuit to get the feel of it, everyone headed to the Isle of Man.

“We were shoulder-to-shoulder with the Sports Motorcycles team in the crowded pits, but were basically on our own and left to our own devices,” Cummins says. “Jim found us accommodation at a private hotel in Douglas that was straight out of Fawlty Towers – I’m not joking!”

The first practice session was an eye-opener.

“The sheer speed made my hair stand on end.Back then you could stand on the side of the road at the pits with no protection. The first bike that went past was Tom Herron on a GP-spec two-stroke and it made the banner on the other side of the road flutter.”

The really hard part for the mechanic, whose job was in limbo for a while after his rider headed off down Bray Hill, was the waiting.

“As we didn’t have spotters around the course, it would be 20 minutes to half an hour before I’d see or hear from Jim after he’d set off,” Cummins recalls. “You’d hear the course announcer talk about conditions and such-like, but they only mentioned the top riders. I was in a bit of a spin for the whole time I was over there.

“I think Jim’s biggest worry was that, as it was his first time on the Island, he might be shown up as not capable. That certainly wasn’t the case and he was running well within the top 15 when he struck trouble in his first race. In the second, he finished just one-hundredth of a second outside the time to get a Bronze replica.”

Scaysbrook chose a particularly difficult year to debut at the TT.

“We made sure we didn’t get involved with the media circus that Mike’s UK manager had created with the Martini-sponsored Yamahas,” he said, recalling it involved a lot of promotion of Yamaha’s new shaft-drive XS1100 model and threatened to overshadow the Ducati effort.

Out on the track, the constant threat of danger and injury soon became apparent. That year there were five fatalities over the 10 days of practice and racing.

“I saw two violent accidents first-hand, and in a sidecar race two riders died at the top of Bray Hill and just minutes later another died at the bottom, so you had three corpses within a mile or so of each other,” Scaysbrook said. “It was sobering. I was up for it, but I also rode well within both my limits and that of the bike.

“That rear slick had no grip but it was impossible to wear out, so I suppose that simplified things. The faster I went the more the cornering reference points changed. It wasn’t until I raced there again in 1980, and again in 1984, that I felt I had the course even remotely worked out.”

Race day brought full focus for the glamour Formula One event and its 63 entrants. This was the race that a year earlier had replaced the Island’s loss of its Grand Prix status. Honda’s Phil Read, the 1977 winner, started in position #1 while Hailwood began in 12th, which matched his number of previous TT wins.

The crowds around the course were living in hope that the Hailwood legend would firstly survive the dangers of this unique course and maybe, just maybe, win. He may have been balding and sporting a slightly paunchy midriff, but the great man put fans’ fears at rest with his first twist of the throttle.

From a standing start, he set his fastest-ever TT lap, 109.87mph. Then he began to hunt Read down on the road, eventually running neck-and-neck with him as they approached their first fuel stops.

Meanwhile, Scaysbrook was on target for a potential 11th-place finish when his throttle jammed wide open on Windy Corner, high on the mountain’s open moors.

“When I pulled the clutch in, it revved its head off but, thank God, I was able to slow enough to ride it off the course and run into a bank to stall it,” he says.

Cummins: “The coil and wiring actually shorted out and fused the cable, locking the throttle half open. The bike came supplied from the factory without an ignition switch; you just plugged a lead into the battery, but that was under the rider’s right leg. Needless to say, after that we wired in a kill switch.”

Scaysbrook was determined to continue:

“I tapped the throttle body to get the slide closed as much as possible, then bump-started it and rode down the mountain using the rear brake to help keep the revs under control.

“It all ended at Governor’s Bridge (the hairpin just before the pits) when the brakes melted and I fell off it. Neil was inconsolable.”

As the pair gathered their thoughts, Hailwood swept to victory while Read’s Honda expired in a cloud of exhaust smoke. The next closest Ducati finisher was Doug Lunn in 14th, while David Cartwright limped home 15th with his rear carburetor hanging off. Among the Ducati non-finishers were Nicholls, whose engine oil-level sight-glass blew out, and George Fogarty (Carl’s father), who fried his clutch.

Second to Hailwood was Read’s Honda teammate, John Williams. Third was Scottish rider Ian Richards on a Kawasaki fitted within an endurance-spec Peckett and McNab frame.

There were just 31 finishers.

Hailwood not only won the race, but also the TT F1 World Championship and set a new class lap record of 110.627mph.

His efforts on the Martini Yamahas didn’t match those on the Ducati. He finished 28th in the Senior TT with machine issues. This was the race where American Pat Hennen set a new lap record then crashed on the last lap, ending his racing career.

Hailwood also had problems in the 250cc Junior race, but finished 12th. Then he retired one lap into the six-lap Classic TT, a race won by Kawasaki’s Mick Grant, whose 114.333mph lap made him the fastest rider ever at the TT. Scaysbrook finished that race in 26th, hampered by a long pit stop to wire-up a broken exhaust.

“Like a true Aussie, Neil cut a bit of wire out of the fence to get me going again,” Scaysbrook says of his mechanic’s ingenuity .

The competition was much tougher than the Formula One race, with Scaysbrook up against a field packed with big two-strokes, such as Yamaha’s TZ750. He was the first Ducati home, and Read’s fourth-placed Honda was the only

four-stroke ahead of him.

So how did the little team celebrate a momentous TT? With Mike Hailwood, of course.

“Mike didn’t like the limelight, he liked ordinary people,” Cummins says. “Eventually he got sick of the drunks slapping him on the back trying to bask in his reflected glory. He said to us, ‘I can’t put up with this, let’s go out to a little seafood restaurant I know at Peel.’

“Anyhow, we finished our meal and Mike spotted an old upright piano. He was soon belting out some beautiful tunes and we were singing our hearts out. That’s the sort of fellow Mike was.”

Words Hamish Cooper

PHOTOGRAPHY Phil Aynsley, Jim Scaysbrook & Neil Cummins