Test Adam Child Photography Jason Critchell

Back in 1999, I was just starting out as a motorcycle journalist. I had hair, a thin waist and no mortgage. At the same time, Suzuki launched its first-generation Hayabusa, and I couldn’t wait to get my hands on one. I was only 23, yet I had the key to a Busa and a private runway all to myself.

Man, that thing was fast. I remember the analogue speedo passing 320km/h, the acceleration nearly ripping away my badly fitting race leathers. I spent the next few months telling everyone about Suzuki’s 320km/h Busa (this was before social media), even though the speedo turned out to be somewhat optimistic…

Yes, in 1999 the Hayabusa redefined the sportsbike class, ripped up the rule book, kicked sand in the face of other so-called fast bikes – it was a monumental step forward. While conventional sportsbikes like Yamaha’s dominant YZF-R1 ruled the twisties and the tracks, the Busa had them all on toast in straight-line performance. In fact, it boasted 30hp more than the R1.

Times have changed. Now, for 2021 (though it’s officially a 2022 model), Suzuki’s extensively modernised Hayabusa is down on peak power and torque, mainly due to the need to meet tight Euro-5 emissions regulations, and even its own GSX-R1000 has more power (and carries less weight) than the new Busa. There are even nakedbikes like Ducati’s Streetfighter with more power, who could have imagined that in 1999?

I was actually wondering if the legend had had its day, whether this might be one revamp too far. Times have changed, 200hp is normal, let alone impressive. Is there really still a market for the bulbous Suzuki, or should it be ushered into the retirement home for a well-deserved rest and a chance to reminisce about the days before traction control and performance-strangling emissions laws?

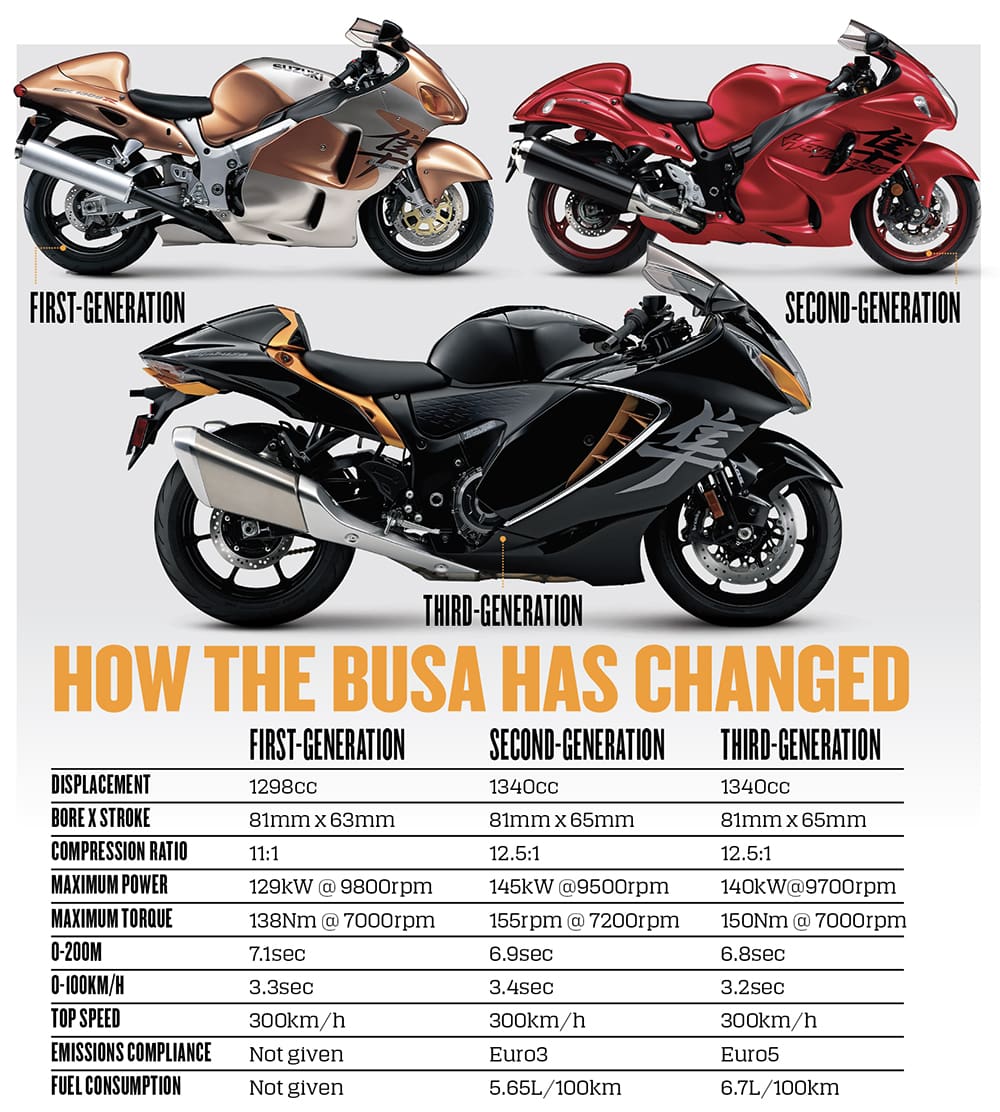

The heart of the Busa remains its legendary 1340cc motor, though those with a keen eye will have noticed a drop in on-paper output. Peak power is now 140kW (188hp) at 9700rpm, down from the 145kW (194hp) at 9500rpm from 2008’s second-generation, when capacity went up from 1298 to 1340cc. (For reference, the first-gen model was 129kW (173hp) at 9800rpm.) Peak torque is also down, from 155Nm at 7200rpm to 150Nm at 7000rpm.

But none of these figures tell the full story, because Suzuki has made significant gains in the mid-range, giving faster acceleration and improving real-world performance on the road. And don’t worry, the Busa will still hit the 300km/h speed limiter with ease.

Although I’m slightly disappointed Suzuki hasn’t added a turbo or increased capacity and push past the magical 149kW (200bhp) mark, I can see why they didn’t. Why make more peak power when it’s already capable of hitting its speed limiter with ease? Like hearing the landlord calling time at the bar and ordering six-pints, it would just be a waste – and 99 percent of customers will never want anything more.

Instead, Suzuki has given the Busa a kick up the midrange with the factory claiming that the new bike is 0.1 seconds quicker to 100km/h and is 0.1 seconds quicker over 200 metres than the second-generation model.

Bore and stroke remain the same and, at face value, the engine doesn’t look dramatically different. But dig a little deeper and the internals are very different, including new pistons, rods, crankshaft, cams, transmission and a new assist-slipper clutch. Some of these changes have been enforced to meet Euro5, but Suzuki has also improved the longevity (improving oil flow, for example) of the Busa, which was already hugely reliable from the start back in 1999.

As I said, I was unsure what to expect from the big Suzuki, particularly as 200hp bikes have become relatively commonplace, but within a few miles of slotting into the new Suzuki, I wound back the throttle and went supersonic – and an immature smile never left my face all day. Wow, the Busa’s still got it.

The midrange acceleration in fifth and sixth gear is superb, but be brave, drop back to second or third, and from 60km/h it just wants to take off. It thrusts forward with such force you can feel your internal organs shifting.

Yes, still got it… still ridiculously exciting.

On a normal superbike, you struggle to use all its power; you’re moving your weight forward trying to keep the front end down while relying on the electronics and aerodynamic wings to keep things in line, whereas the Suzuki is old school. Weight distribution is stated at 50:50 but the Busa sits slightly on its relatively soft KYB rear shock, and the bespoke rear Bridgestone S22 combines with a long wheelbase to find sensational mechanical grip and propel you forward at an alarming rate.

Reaching 160km/h in just over five seconds, around 11 seconds to 240km/h… how fast do you want it? I couldn’t stop kicking back a few gears on the (standard) up-and-down, super smooth quickshifter just to experience that acceleration again. Hitting 160 clicks is nothing, over 210km/h is gone in a flash. Yes, it’s hard not to speed on the Hayabusa, officer…

However, the new bike hasn’t just been designed to tear up dragstrips or embarrass almost any bike from the lights, there is a practical side to it, too. It isn’t a caged animal clawing at the bars; in fact, in a normal riding environment it’s a usable and, dare I say, friendly motorcycle.

Central to this is that Suzuki has significantly improved and updated the electronic rider aids, with a new six-axis IMU now linked to three rider modes. The softer of the three modes noticeably restricts the power and torque, making the Busa feel docile in comparison to the full-power mode. Meanwhile, the quickhshifter works fluidly, even at slow speeds, and the gearbox is light. So you can ride the Busa ‘normally’, just.

Previously the rider controlled the power, now we have clever electronics to do it for us. Riders who think even bikes with this much torque don’t need rider aids are, in my opinion, probably wrong. If ever a bike needed clever electronics, it is the Hayabusa. Early first-generation models, running on poor rubber, would light up the rear tyre with ease, while riding a Busa fast in the wet required surgical precision with the throttle – but not anymore. Now much of the thinking is handled by clever and lean-sensitive rider aids.

That new six-axis IMU enables lean-sensitive ABS braking, traction control, wheelie control (anti-wheelie), engine braking control, and those three power modes with varying levels of engine performance. There’s even launch control, which limits the revs to 4000rpm, 6000rpm or 8000rpm. Add the quickshifter (which, incidentally, is changeable) and anyone can now launch a Busa off the line with ease and in safety.

There are six modes to choose from: three being pre-set and three you can personalise. Essentially, the three pre-set modes offer varying levels of control, from full power and minimal rider aids to reduced power and intrusive rider aids. The three personal settings are just that, and can be tailored to how and where you ride. You could, for example, opt for full power and no rider aids (ABS can’t be deactivated, however) or, alternatively, you may love the full power experience but want maximum traction control (rating from 0-10) and maximum anti-wheelie.

All this is accessible via new and simple switchgear and is clearly displayed on the TFT clocks, between the analogue speedo and rev counter, which remain triumphantly old school. Not only do I applaud Suzuki for keeping with traditional dials – watch those needles spin! – I like the way it has also made the rider aids accessible, useful and easy to navigate.

Better still, you can flick from, say, low power with full rider aids to a personalised hooligan setting of no rider aids and full power whilst on the move. Once you’ve saved your setting, they remain saved, even when you switch off the ignition. You can even change the layout of the TFT to display various features like lean angle, which again is very neat, clever and easy to understand. Like all new bikes, the switchgear and dash take a little getting used to, but without reading the manual, I had it sussed by the end of the day’s ride.

Another welcome feature of the new package of electronic rider aids is their inherent smoothness. It doesn’t feel like someone is removing a sparkplug when the anti-wheelie kicks in, even in the most intrusive settings. Thankfully, the ABS isn’t overly intrusive and is a welcome aid when you’re running out of runway at 290km/h plus, believe me.

Braking was always a weak point of the Hayabusa. Even when Suzuki uprated the brakes to Brembo items from Tokicos in 2008 and added basic ABS, they still weren’t the best, especially by modern standards. The combination of a relatively heavy bike, a long wheelbase and all that power meant the stoppers were always going to take a hammering. Suzuki has rectified this by spending some cash on the latest Brembo Stylemas radial items, larger 320mm discs and, as mentioned, cornering ABS (in partnership with Bosch). The brakes are also now linked – front to back, but not back to front – and there’s three-stage engine braking strategy, plus slipper clutch as standard.

The result is stopping performance that’s a significant step over the previous model and would thoroughly embarrass the original Busa from 160km/h to stopped. Even after heavy use on the runway, there was virtually no fade, despite some abuse. On the road, the introduction of cornering ABS is a welcome addition.

The twin-spar frame is essentially the same as the previous model, and externally, the KYB 43mm forks and KYB rear shock, appear to be remarkably similar, too. However, Suzuki assures us the suspension has been reworked with new settings, spring and valves. Front-fork rigidity has also been improved and the result is quality. Stability, which has always been a strong point of the Busa, is unquestionable. You could update your social media account while riding flat out, though I wouldn’t recommend it. Bumps, undulations, big handfuls of throttle… through it all it remains unfazed, like a well-disciplined soldier.

At 264kg and with a long 1480mm wheelbase, the handling isn’t razor sharp, but for a big bike it can take you pleasantly by surprise. It appears Suzuki hasn’t thrown the R&D money at the handling like they have the electronics and brakes, yet it somehow seems to work. The changes they’ve made, combined with excellent Bridgestone Battlax Hypersport S22 rubber, specifically designed to work with the Busa, means it handles far better than I remember. It takes on bumps and imperfections with unruffled ease and will happily lay on its side to knee-down extremes, feeling planted and tracking accurately.

I can’t remember the old bike being this easy and well-mannered in the bends. The Busa devours fast, sweeping corners like a child devours easter eggs. Sure, ride aggressively, dive for apexes, hit the power hard over bumps, and you’ll get some complaints, while pegs will start to scrape if you want to pick a fight. But the Busa was never designed to be able to cut it on track; if you want that opt for a lighter, more powerful GSX-R1000. However, after a few hundred kays of road riding, I know which bike I’d prefer.

I’ll probably receive lots of hate mail on this, but I never found the old model particularly comfortable. I see loads of riders using the Busa for touring, fully loaded with panniers and pillion, and think, why? For me, and I’m only 170cm, the bars were too low, the screen too small, and the pegs too high. There, I’ve said it.

But Suzuki has rectified a few of my criticisms, by moving the bars 12mm closer to the rider. That may not appear to be much, but it makes a real difference, especially at slow speeds when you have lots of weight on your wrists.

The pegs are still relatively high. I’m presuming Suzuki couldn’t lower the pegs due to already-limited ground clearance, and the new bodywork is an improvement, but the screen is still on the low side. As mentioned, I’m below average height, and I’m sure taller riders will be adding a larger screen for touring (the optional extra is 38mm higher).

Cruise control now comes as standard, which is a great addition, and there is even a speed limiter for those pain-in-the-arse average speed cameras. Easy start, low rpm assist and hill control add to an already impressive list of standard equipment. And as you’d expect, Suzuki offers a range of accessories, but, luggage-wise, only offers a tank bag (small or large) in their range of genuine products.

But before you book your next Busa adventure, we have a small hiccup.

Euro-5 restrictions mean fuel consumption has increased, yet the fuel tank size has remained the same at 20 litres. Suzuki is claiming 6.7L/100km, from 5.65L/100km on the previous model, which is a significant drop. This means the theoretical range from the 20-litre tank has dropped from 354km to 298km. Obviously, we never run a bike until it’s empty, but this does mean you’re going to be searching for fuel sooner on the new model.

Interestingly, I managed 6.1L/100km on the test (before we let loose on the runway) which was down on the previous generation-two model, but not as poor as Suzuki’s claimed figures. It will be interesting to see how the new Busa performs when we can get some serious kays under our belts over a few days, rather than on a one-day test.

I can’t believe we have got this far without mentioning the looks. Are you a fan? From what I can tell so far, the styling divided opinions. Some love it, some hate it. I congratulate Suzuki for staying with that familiar Busa styling, it’s immediately obvious this is a Hayabusa, even the silhouette screams Busa.

I like the new looks and, strangely, the bike looks better with a rider onboard than standing alone on its sidestand. The rider finishes the lines and makes its sleek aerodynamic shape complete.

The integrated indicators and rear light neaten up the rear end, and I even like the new exhaust. Onboard the pre-mentioned dash is neat, clear and easy to understand, while personally I don’t care that there isn’t any Bluetooth connectivity. The switchgear is simple and thankfully uncluttered. Everything feels solid, well thought out and, without wishing to be too harsh, at a higher level than other recent Suzukis.

Some models in Suzuki’s range don’t have the high-end feel of quality like their Japanese competition from Honda, Kawasaki and Yamaha, but the same can’t be said for the Hayabusa. In terms of feel and quality, this is on a par with the very best of the competition and, like the old model, the engine should be bulletproof. The only slight negative is the price which has risen significantly since the second-generation bike was discontinued in 2018. It’s also significantly more expensive than Kawasaki’s ZX-14R and, price-wise, is now more on par with Kawasaki’s supercharged Ninja H2 SX.

It’s not often I admit being wrong. But when I feared Suzuki’s legendary Hayabusa may have had its day, I was as wrong as a road tester can be. It has still got it and it still delivers – so much so that I didn’t want to give the key back.

Suzuki hasn’t gone chasing peak power, as doing so would be wasted given that it is restricted to 300km/h. Instead, it has looked at how it can improve the experience without spoiling the essence of the Busa. It’s added advanced rider aids, a sleek design, updated TFT clocks, much-improved brakes and increased comfort – ticked all the boxes the ageing machine needed ticked, yet it still looks and feel like the original legend.

The engine may have lost some top-end power but it has gained in the midrange, and takes your breath away every time you crack open the throttle. It’s hard not to ride extremely fast on the Busa.

Some may not like the design, some will turn their noses up at the reduced fuel range, and a small percentage will not like the relative lack of more top-end power, even though it would only be good for impressing uneducated mates down the pub.

But for me, the Busa is still one of the fastest and most thrilling ways of getting from A to B in comfort, only now with more style, safety and real-world grunt than before.

The legend continues.