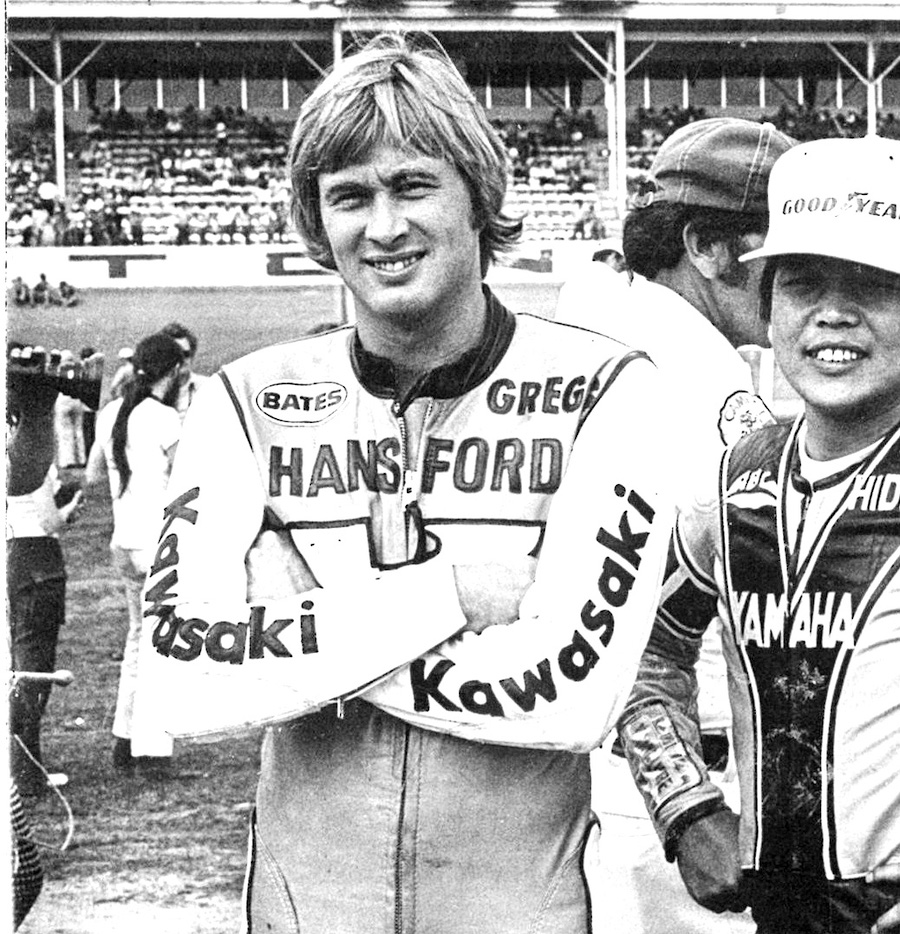

Bathurst race fans received a star-attraction bonus at Easter 1980. Gregg Hansford, rated the number-five rider in the world by prestigious yearbook Motocourse, raced on the Mountain – while his peers were at England’s Trans-Atlantic Match Race meetings or France’s Circuit Paul Ricard for the Moto Journal 200km.

Hansford was a few days short of his 28th birthday and Australia’s most successful rider in terms of world championship grand prix victories. He had won 10 world championship GPs and four world Formula 750 championship races in the previous two and a half years.

The Queenslander was, and still is, the only Australian to win a GP in his rookie season. There were huge expectations on Hansford when he joined the GP tour in 1978, the first Australian road racer to debut in the GPs as a works rider. That year he won seven classics, including 250/350 doubles at France’s Nogaro circuit, Sweden’s Karlskoga and Rijeka in the old Yugoslavia.

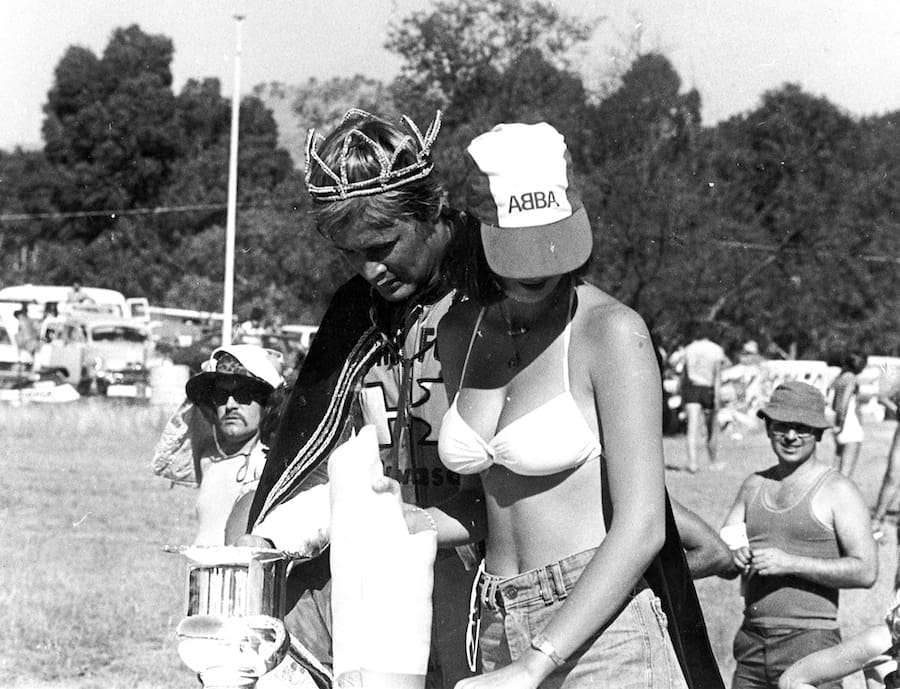

It is some record. On the national scene, Hansford’s achievements included four Australian Unlimited Road-Racing Championships, the 1975 Castrol Six-Hour Production Race with Murray Sayle and the 1976 Australian Unlimited TT at Laverton. He would go on in 1993 add a Bathurst 1000km car-race crown with Larry Perkins – a unique Bathurst Australian motorcycle GP/Bathurst tin-top double.

But there are some Hansford career factors to ponder. He only rode a 500 in his early days, racing a Kawasaki H1R in 1972, and he only started in three world 500 championship races. He retired from the first one at the Nürburgring in August 1980 when his steering damper broke, sending his Kawasaki KR500 into a massive tank slapper.

During his third 500 start at Spa-Francorchamps on July 5, 1981 he took an escape road due to inoperative front brakes and crashed into a marshal’s car that had been parked there! Hansford sustained a broken femur and suffered blood clots that ended his two-wheel career.

We’ll return to the issue of why Gregory John Hansford was smashing lap records at Mount Panorama in early April 1980 and not contracted for a third season on the GP stage. He had competed toe-to-toe with the likes of Kenny Roberts, Kork Ballington, Johnny Cecotto and Randy Mamola, been runner-up twice to Ballington in the world 250 championship and twice finished third in the 350 title.

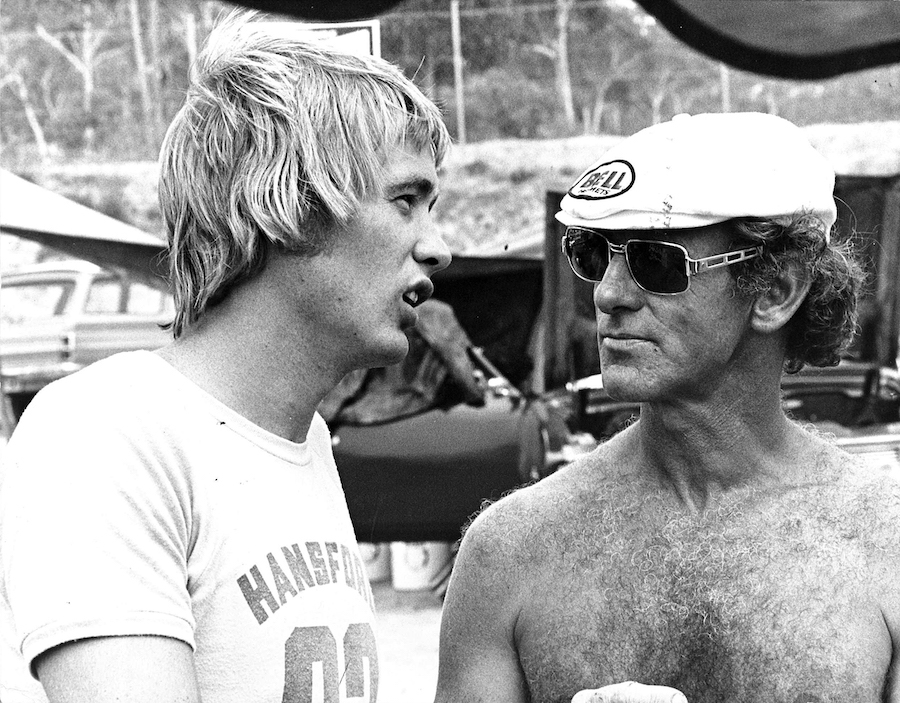

But first, a re-cap on an international career that began in March 1974 when Hansford rode one of the newly released Yamaha TZ750 machines in the Daytona 200. Good friend Warren Willing accompanied him as mechanic. Back in Australia, Willing secured a TZ750 for Bathurst and the two 21-year-olds fought the main race down to the wire – capturing media and fan attention, and becoming a double drawcard wherever they faced off in Australia for the next three years.

This rivalry gained an added dimension in 1975 when Team Kawasaki Australia manager Neville Doyle hired Hansford to ride alongside Ron Toombs and Murray Sayle.

Hansford made short forays overseas to Daytona and to selected Formula 750 races in Europe over the next three years. In 1977, he stayed in Europe over Easter rather than return for Bathurst.

Later that year, Hansford won both races in the world Formula 750 Championship round at Mosport Park in Canada and a won United States national 250 race at Laguna Seca, out-foxing US veteran Gary Nixon on the last lap.

So impressive was Hansford’s riding on these trips that editor Chris Carter in the 1977-78 edition of Motocourse rated Gregg number five in the world – before he’d even started in a GP.

Bottom line? Hansford was ready for bigger things. As local rival Jeff Sayle reminded us recently, Gregg was so brilliant he had to go. Kawasaki was assembling the tools for the job. Kawasaki’s tandem-twin KR250 claimed two world championship 250 GP victories in 1977 and a 350 version was slated for ’78. Doyle had a wealth of experience with the KR250.

One was Hansford’s great strengths was braking and Doyle gave him an edge by grafting KR750 front forks and twin-disc brakes into Gregg’s 1977 250 machine. Interestingly, the ’77 model was rolled out for some GPs in 1978 when the new model had problems. It’s easy to spot in images from Assen for example, because it had a plain green fairing with TAA (Trans Australia Airlines) stickers.

The Hansford-Doyle plan was ambitious – to race in the world 250 and 350 GP championships and, when the calendar allowed, the world Formula 750 title as well. All this from a team that initially consisted of Doyle as manager and maintaining the machines, and his wife Margot with the stopwatches and paperwork.

Hansford wasn’t the only high-profile GP rookie in 1978. America’s Kenny Roberts had a similar dance card of 250 and 500 GP, and F750. Yamaha America team boss Kel Carruthers (Australia’s 1969 world 250 champion) built a special 250 for the quarter-litre campaign.

New to Kawasaki, but certainly not to the GPs, was South Africa’s Kork Ballington, who had been in Europe since 1973. A 250/350 double victory on private Yamahas at the 1977 British GP had sealed Ballington a place in Kawasaki’s British team. His main technical man was elder brother Deryck, aka ‘Dozy’.

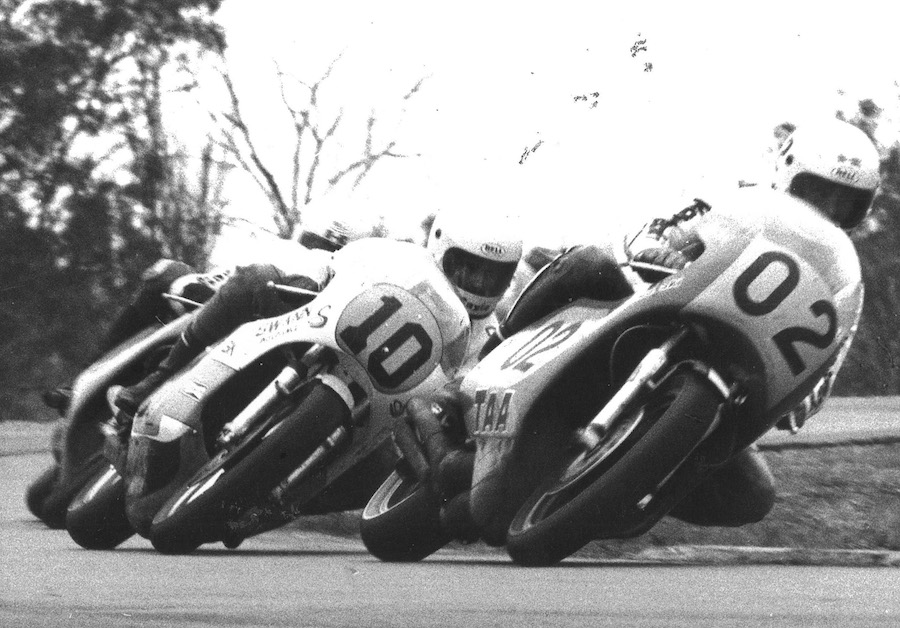

This trio would meet in the 250 class, using different tyre brands – Michelin for Hansford, Goodyear for Roberts and Dunlop for Ballington. The result was lap records knocked sideways. Roberts stopped racing his 250 after six rounds to concentrate on his 500, with the score line of: Hansford two wins, Roberts two, Ballington one and Morbidelli’s Paolo Pileri one.

Here are some fastest race lap comparisons: Roberts took 2.3 seconds off Walter Villa’s 1977 record in Venezuela; Hansford lopped three seconds off Takazumi Katayama’s best 1977 time at Jarama (after Hansford and Roberts missed the first day’s practice arguing with Spanish organisers to secure a start) and Ballington cut 2.5 seconds from Villa’s 1976 record at Mugello. The next time the Italian GP was held there, in 1982, the fastest lap was a tenth slower than 1978.

Ballington beat Hansford by a half a wheel in the 250 GP at Mugello in 1978 and both riders were credited with identical race times – a massive 76.9s under Villa’s 1976 time for 23 laps.

Ballington in his autobiography Ballington Unkorked said it was the best ride of his career and the turning point in the 1978 championship. In 1998, chatting with a group of former Australian internationals during the massive Centennial Classic TT event at Assen, he opined: “Gregg was the hardest guy I raced against. I had to ride at a level I previously didn’t know existed to beat him.”

Hansford reckoned the biggest buzz of his career was winning the ’79 Dutch 350 TT in front of 200,000 fans.

Hansford was a rapid learner of new circuits. The Swedish GP was shifted to Karlskoga in 1978 and Hansford qualified fastest for the 350 GP with a better time than Johnny Cecotto posted in the 500 class. At Nürburgring in ’78, Gregg was fastest 250 and 350 qualifier, on his first visit to the 22km circuit.

At season’s end, Hansford had won seven GPs, missed finished second in the 250 title six points to Ballington and was third on the 350 table, one point behind Katayama, with Ballington first. He had won one F750 championship race, at Assen.

New Motocourse editor Barry Coleman rated Hansford number five in his top 10 and wrote: “Gregg Hansford suffered three great handicaps in 1978: his size in relation to the small bikes he had to ride; the lack of power of his 750; and the distance between Australia and Europe. His size would matter much less on a 500 and he could undoubtedly get hold of a fast 750 (but not without a change of employer). Australia will probably stay where it is, but riding bigger, faster bikes and winning races on them would no doubt make Hansford feel much more at home in Europe. On a tight track on a fast bike, no one in the world would count on beating him. He is near unbeatable on the corners and he is the best braker in the business.”

Hansford signed off the 1978 season with a GP double at the newly opened Rijeka circuit, but the 1979 season began with a run of mechanical and tyre dramas. Added to that, Kawasaki’s new four-cylinder 750 had vibration problems.

He won three GPs in ’79, all in the 350 class, but none in the 250 championship – in which Valentino Rossi’s father Graziano won three times on the factory Morbidelli. Once again, Gregg finished second in the 250 championship and third in the 350. France’s Patrick Fernandez leap-frogged him for second place by winning the last 350 round at Le Mans. Hansford won one race in the F750 championship at Nogaro on his trusty three-cylinder KR750. His last GP victory was the 350 event at Karlskoga, Sweden, on July 22, 1979, a little over 15 months after his first classic victory in Spain.

It was not just the results that upset Gregg Hansford in 1979 and his dislike of being away from home. It was a time of general discontent in GP paddock at the way the sport was run by the FIM and national bodies that organised their home GPs. Roberts for one could see the sport’s potential.

A call to action came with the 1979 Belgian GP debacle. A new circuit had been created at Spa-Francorchamps, shortening the blindingly fast 14km public-road layout. Problem was, construction ran late over a very cold winter and the final tarmac surface was laced with diesel to speed the curing process. Riders discovered in the first practice session it was more like riding in the wet. The works riders called for a boycott.

This brought together Roberts, Sheene and Hansford with Barry Coleman to seek a better deal. They proposed their own championship, known as World Series.

However, Hansford’s loyalty also to came into play at the end of 1979. World Series was looking a real possibility and that placed the Japanese factories in a bind. Would there be two series in 1980 and which series would they support? The traditional FIM series or this new series that seemed to have attracted the best riders. Plans were made to contest both.

Roberts and some other were adamant they would ride only in the World Series. That gave Hansford a chance of becoming a works Yamaha 500 rider. It was very tempting, with most of his major rivals contesting the 500 class while he was stuck on 250s and 350s. Yamaha was committed to Roberts, whatever decision he made. So it needed a 500 rider for the world championship. It offered Mamola and then Hansford contracts to contest the 1980 world 500 championship.

Austrian journalist Günther Wiesinger was mates with Hansford and saw this as his big chance: “Yamaha was prepared to give bikes to Kenny for the World Series and to Gregg for the world championships. But Kenny and Gregg threw me out of the motor home when I tried to stop Gregg signing for the World Series,” Wiesinger said.

Roberts confirmed the Yamaha opportunity to the author in a 1988 interview.

“My contract with Yamaha applied to whatever series I chose. Yamaha wanted Gregg to run in the world championships, but he refused it. When everybody was forced to go back to the world championships, that put me back in the number-one spot in the Grand Prix team and the previous offers to Randy and Gregg were closed.”

In the end, World Series didn’t happen. Several circuit owners who had initially put their venues forward developed cold feet when their national motorcycle bodies told them that if they did host a World Series round, it would be the only motorcycle race they’d run all year. One positive from the whole exercise was a substantially increase in GP prize money.

The demise of World Series left Hansford stumped. He didn’t want to do 250/350 in Europe again, and all the factory 500 rides were sewn up. So while Roberts, Mamola, Rossi Snr and the rest went back to racing 500 GP, Hansford stayed in Australia to ride Kawasaki 250s and 350s in national title meetings and the Australian GP, and a new 1000 endurance race at Oran Park and Bathurst as preparation for Suzuka.

Kawasaki was developing a 500 racer and signed both Hansford and Ballington to ride it. Here we have the great double ‘what-if’ of the period. In 1978, Suzuki had been so impressed with Hansford’s debut GP season it sounded him out for a 500 ride. The following year – and this was at the time Barry Sheene and Suzuki parted ways – Ballington was in the frame.

Some suggest that the Suzuki ride was Ballington’s for the taking, but he asked for too much money. Ballington says he stayed with Kawasaki for two reasons: the money was better and he figured Kawasaki would be more loyal to him if he didn’t succeed in the first year.

Hansford’s friends lament that he didn’t somehow take the Yamaha offer. In the 1980s he made the occasional comment that perhaps he shouldn’t have been so keen to have Roberts think he was a great bloke.

It sometimes suggested that Hansford had no choice but to stay with Kawasaki in 1980. It was the comfortable, known choice to stay with Doyle and the factory he knew. But there were alternatives. One option was to source a private Suzuki and find a sponsor to run it. The Suzuki RG500 was a proven package – as shown in 1979 when Italy’s Franco Uncini and Holland’s Boet van Dulmen finished fifth and sixth in 500 championship on Mk IV Suzukis and both took podium finishes on their private machines. Mike Baldwin, a Kawasaki rider in the USA, put another private Suzuki on pole position for the 1979 Spanish GP and finished third. Randy Mamola put the very same machine on the podium at the last GP of the season in France, just 2.4 seconds behind race-winner Sheene’s works bike.

But part of Hansford’s charm was he did not fit the cliché of a brief-case carrying sponsorship chaser. His view was that sponsors would come to him if he showed the goods on the circuit.

In August 1980, Hansford returned to GP racing at the Nürburgring. He retired the KR500 with a broken steering damper while Ballington finished 11th, also troubled by the machine wanting to shake its handlebars. Gregg rode in the 350 class too, qualifying second and finishing fifth.

Kawasaki launched its full 500 effort in 1981, with Hansford and Ballington riding monocoque chassis machines. Hansford would later confess that the chassis gave him nightmares for years afterward.

Hansford’s effort was interrupted almost immediately, missing five GPs. He qualified fastest for the Imola 200, but lost control on a damp patch on one of the fastest sections of the track and crashed, sustaining a fractured tibia.

Two races back from the Imola injury, Gregg’s motorcycle career was ruined in the freak accident at the Belgian GP, when he crashed into the official’s parked on the run-off road. He sustained a broken femur and had serious problems with blood clot that took five years and many operations to correct.

Ballington raced the KR500 through 1981 and 1982, with his best results being two third places. He loved the square-four rotary disc valve engine and its reliability, but the bike was too long and too heavy to be a GP winner.

The nearest he came to winning a GP came when Kawasaki produced a shorter swinging arm for the ‘81 British GP. And then the engine broke a disc valve. Ballington left the GPs when his Kawasaki contract expired at the end of 1982.

Hansford switched to car racing, winning the 1993 Bathurst 1000. In 1995, he secured a full-time drive after seven years of part-time efforts, joining the 2-Litre Super Touring Class. In his very first competitive drive in a front-wheel drive car, Gregg’s Ford Mondeo turned sideways at Phillip Island’s Turn One. He crashed into the wall on the inside of the turn and died. It was March 5, 1995.

Hansford’s 10 world championship GP victories place him fourth highest on the overall Australian GP win table, behind Michael Doohan, Casey Stoner and Wayne Gardner. He was the second most successful rider never to win a world championship. Randy Mamola won 13 GPs and was a title runner-up four times.

Setting Hansford apart is the fact did his GP winning in just two seasons.

Words Don Cox Photography AMCN archives