During the four weeks before the decisive and last race of the 1983 grand prix season, Freddie Spencer didn’t sleep very well. In the middle of the night, he found himself thinking about what could happen in Imola on 4 September, when he was going to have the chance to clinch his first world title against compatriot Kenny Roberts.

Thoughts, doubts, questions and answers filled his mind. Different scenarios: winning or losing, celebrating or crying. The line between the two outputs looked very thin. Everything at that time was uncertain.

Spencer and Roberts couldn’t be more different. Spencer, the rider from Louisiana was in the first part of his grand prix career, a youngster ready to challenge the heroes of the time.

Roberts, the 31-year-old from California and born a decade earlier, already had three premier class titles to his name and was about to retire, chasing the perfect fairytale ending. They rode for different manufacturers and each of them had their own motivations. They both wanted the same thing: the crown.

The 12-round season kicked off in Kyalami in South Africa and ended at Imola in Italy, where the pre-race commentary described it as “the tensest moment I have ever known in motorcycle racing.”

During the season Spencer and Roberts scored six pole positions apiece and between them took every victory on offer – again, each celebrating six wins a piece. Nothing separated them.

The season started in the best way possible: you won the first two races and then went to Monza, which was not the best track for your Honda.

Kenny and I had different bikes in terms of characteristics, and our riding styles were different. He liked to have more weight toward the rear, which allowed him to be able to have more rear grip. I liked more toward the front, which allowed me to run a different mid-corner line. His V4 had good power and was quick in the tracks with big corners. My V3 was a little bit lighter and working well in stop-and-go turns. I was on Michelin rubber, he had Dunlops.

The Italian track was very fast, with long straights: I guess your expectations weren’t too high?

On Thursday my crew chief Erv Kanemoto and I went and looked at the corner where, 10 years before, Jarno Saarinen and Renzo Pasolini were killed. It was so tragic and it contributed to the image that this great track had for me, like a cathedral.

I always dreamed that if I was going to win the Italian GP, it had to be in Monza. I told Erv ‘I really believe we can win this race’. He said ‘This is the worst track for our bike, because of the speeds and the high gear ratio. Our three-cylinder, compared to the V4, doesn’t have a lot of midrange torque. You’ll have to ride very hard”.

Roberts got pole, but in the race you were able to stay with him.

I was really fast in the three Ascari corners, left-right-left, leading to the back straightway. The front-end would tuck, I would save it on my knee, full throttle, and then I could get a good drive. Instead of being right behind him, my momentum would carry me out to the right of him. As we would go to third and fourth, he would out-accelerate me, but because of my drive onto the back straightway I was able to stay behind him.

In the following right corner, the Parabolica, which was the last turn, I would go up the inside and I did that. I was pushing, pushing, pushing, thinking that I could go inside him. We kept going deeper and deeper and deeper. At one point, while he was in front of me, he ran too hot and ran off the track on the outside. When he tried to get back on the track he fell off.

You won the race even if you weren’t the fastest.

I think that Kenny’s assumption was that I was going to pass him on the inside of the last corner in the last lap, and I was going to be able to stay in front until the finish line. He didn’t realise that I was barely hanging on. On the finish line, every lap, he was 10 bikes ahead. He just didn’t know it.

How confident were you after Monza?

You know, there’s always that little place in you, in the deepest place of your psyche, where you ask: is it your time to do it? After winning the first three races I thought: absolutely. But my practical side knew that Kenny was probably going to retire after 1983 and also that the Yamaha would be stronger as the season went on.

In fact, Roberts started to fight back. In general, one thing you rarely missed was a good start and a great first lap: what was your secret?

In those days we didn’t have tyre warmers and we would have a sighting lap, then a break, and a warm-up lap. The temperature outside was cold, as it often was in Europe. Sometimes I started the race on a brand new tyre if I felt that it was out of balance in the sighting lap. So I may have started with just one lap on the tyre. I knew I was going to ride on a tyre that wouldn’t have as much grip initially. What did that mean? Two things had to change. I needed a bigger radius and less lean angle so the tyre could move and I could control it. And I had a bigger chance to save it. My lap time didn’t get too affected because I wasn’t locked in the radius and lean angle that I would use when the tyre got into temperature.

Was it a natural skill for you?

When I was about four I would ride a Briggs & Stratton minibike, nothing very sophisticated, around my house in Louisiana. We lived out in the country, we had two acres of land. There were often leaves on the ground and it rained. I would look ahead at what was in front of me and I would see if the leaves were dark coloured or light coloured. That would determine the angle and trajectory of the bike, if I was leaning or leaning less, depending if it was slick or dry.

And from what I would feel in the movement of the bike, I would determine how much throttle I could give. That’s the same skill I used in the first lap of a GP. I developed it at that young age.

Back to the 1983 season: after 10 rounds, and with two left, you and Roberts had won five races each. Next stop: Sweden.

Anderstop was pretty bumpy, with stop-and-go corners. It had to benefit our bike. In qualifying it looked that way. But after a few laps I realised that Kenny did a great job at sandbagging. He was running quicker than we did in qualifying. He went in front. We were going to have a great battle.

Again, you had to develop a strategy for the race, like in Monza?

Yes, and at the same time I was at the very edge of my bike’s performance. Everything was happening at this incredible speed of inputs and reactions. You’re running at 170mph (274km/h) down the straightway, with all that wind noise, the bike is moving around, and at the same time part of your brain is calculating and you’re paying attention to the competitor; is he using less lean angle in this corner than the lap before? Is he getting on the throttle at the same point, or earlier, or later?

What did you figure out?

My only chance was to make a pass at the end of the back straightway. What Kenny didn’t realise, because I had never been in front of him except at the very beginning, was that I was barely able to stay with him off the corner exit down that straightway. So I couldn’t get next to him to try to outbreak him into the first of the two last right corners before the finish line, which were separated by a short chute. The last corner leading onto the back straightway was a little bit banked on the entrance. On the exit it rolled off a little bit. With five or six laps to go I thought that if I could get in and maybe move and tighten up the entry line, two things might happen: one, if Kenny tightens his entry and then keeps using more lean angle, maybe it might affect his drive and I can get the run on him; and two, he might make a mistake of some kind.

What happened in the last lap?

I was right behind him, I showed him a wheel in the entrance to that right-hander before the back straight, but instead of going under him as he expected I actually went into the turn a little bit higher so I could get the drive off the corner. In the exit, under acceleration, he lost traction, while I got the best drive of all my race.

We were going down the straightway and we were next to each other. I was on the inside, he was on the outside. Because we were doing this all weekend, we developed a skill where we would just feel where we needed to get on the brakes. So I was paying attention to what I was doing but at the same time to what he was doing next to me. At the last second, instead of watching him, I turned my eyes and watched his hand.

When he went to sit up, he didn’t brake. In that split second I decided that I wasn’t going to brake until he did. When he finally braked, I sat up, and we were both too deep into the corner.

There was a lot of controversy regarding that manoeuvre. Did you touch?

No. There was no one down at that corner, like it is now. From a lot of angles it looked like I pushed him off the track. The truth is, I was a little bit wide but so was he. When we came off the corner I had a better angle, I got on the throttle, I was in front and I won.

Your strategy worked again.

You know, I had been watching Kenny since I was 11 years old, I knew everything he could do with a bike. I had been basically preparing myself for that battle for the previous 10 years. And it all came down to that moment, when I turned my eyes and looked at his hand, when he sat up and didn’t roll off the throttle.

Do you have clear memories of all the phases involved?

Sure, if I close my eyes I can still see his red right glove while he maintains the throttle.

How did Roberts take losing?

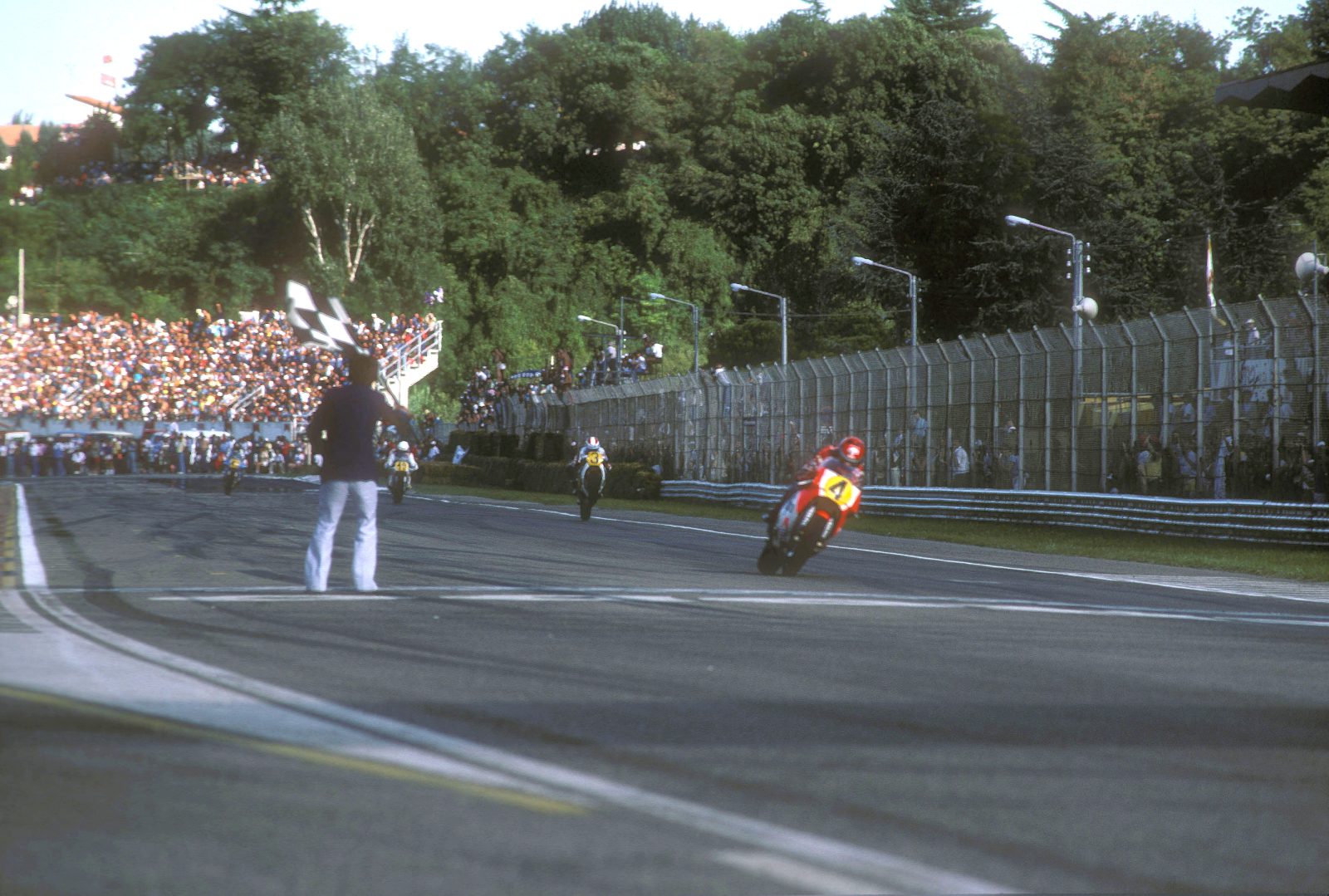

He was extremely upset because he knew that with my victory there, in Imola I could finish second and put my hands on the title even if he won.

After Sweden you had to wait for almost a month before the last race. Were you relaxed?

I can’t tell you how many times I woke up in the middle of the night. I was nervous, thinking about all the possibilities.

In Imola you finished second behind Roberts: job done. Looking back, which was the most important result that contributed to the title?

Monza.

Interview Jeffrey Zani + Photography Gold&Goose, Craig Howell, Martin Cox, Credric Janodet & Mike Clarke