Right now in this country, cost and practicality are the two biggest barriers to electric vehicle ownership. So while there’s an increased willingness to make more sustainable decisions around how we move around our cities, the size of the pool of potential electric bike owners is more or less decided by the distance of their commute and the depth of their pockets. This makes what 39-year-old Michelle Nazarri is doing with her two-model range of Australian-made commuters as courageous as it is clever.

Because not only are the Fonz-branded machines utterly customisable in all the conventional ways we’ve come to expect, but the motor, the controller, the power pack and the charging infrastructure can all be customised to suit both your budget and individual needs.

I’m riding the NKD, which is the flagship nakedbike that sits alongside the less-expensive scooter called Arthur. Other than getting your head around the NKD’s unique and polarising styling, the first thing you’re struck by as you approach the NKD is the surprisingly high build quality. Take the ’bar-end indicators and shmick borderless mirrors which use chiselled aluminium instead of a glass insert, for example. Both are part of the firm’s extensive list of options, but certainly not things I expected to see on a sub-$15k bike which rolled off an assembly line in Sydney’s inner south.

There used to be four ‘starting’ versions of the NKD, but the least-expensive base model has been dropped due to poor sales, which leaves the NKDs, the NKD+ and the NKDx, whose differences basically come down to performance. I say starting, because once you’ve settled on your performance spec, the long list of choices continues to things like mirrors, bodywork material, frame colour, seat (shape and material – there’s even vegan leather!), tyres, chargers, grips, luggage – even a surfboard mount – before your order is sent off to the local assembly line.

And of course, because they’re put together in Sydney, if you really do want a base model, Fonz will accommodate.

The NKDs has a top speed of 100km/h from its 8.6kW motor and a claimed range of 100km of urban riding. The NKD+, which I’m riding, has the same top speed of 100km/h, this time from a 9.6kW motor and range is extended to a claimed 140km. The top-tier NKDx gets an 11kW motor, a top-speed capability of 110km/h with range as high as 200km if ridden in Eco mode.

Eco mode is one of three selectable maps standard on all three variants, joining Street and Beast. And while an Eco mode on other electric commuters I’ve ridden would reduce acceleration or restrict speed quite noticeably, I couldn’t really discern any difference between the three modes on my admittedly short inner-city test ride.

It’s a similar customisable story with the charging infrastructure. All three come standard with a basic trickle charger which takes 11 hours to charge the NKDs, around 14 hours to charge the NKD+ and almost 20 hours to recharge the NKDx, but there are two more options that you can choose to include – or even have all three – to align the charging times with your individual circumstances.

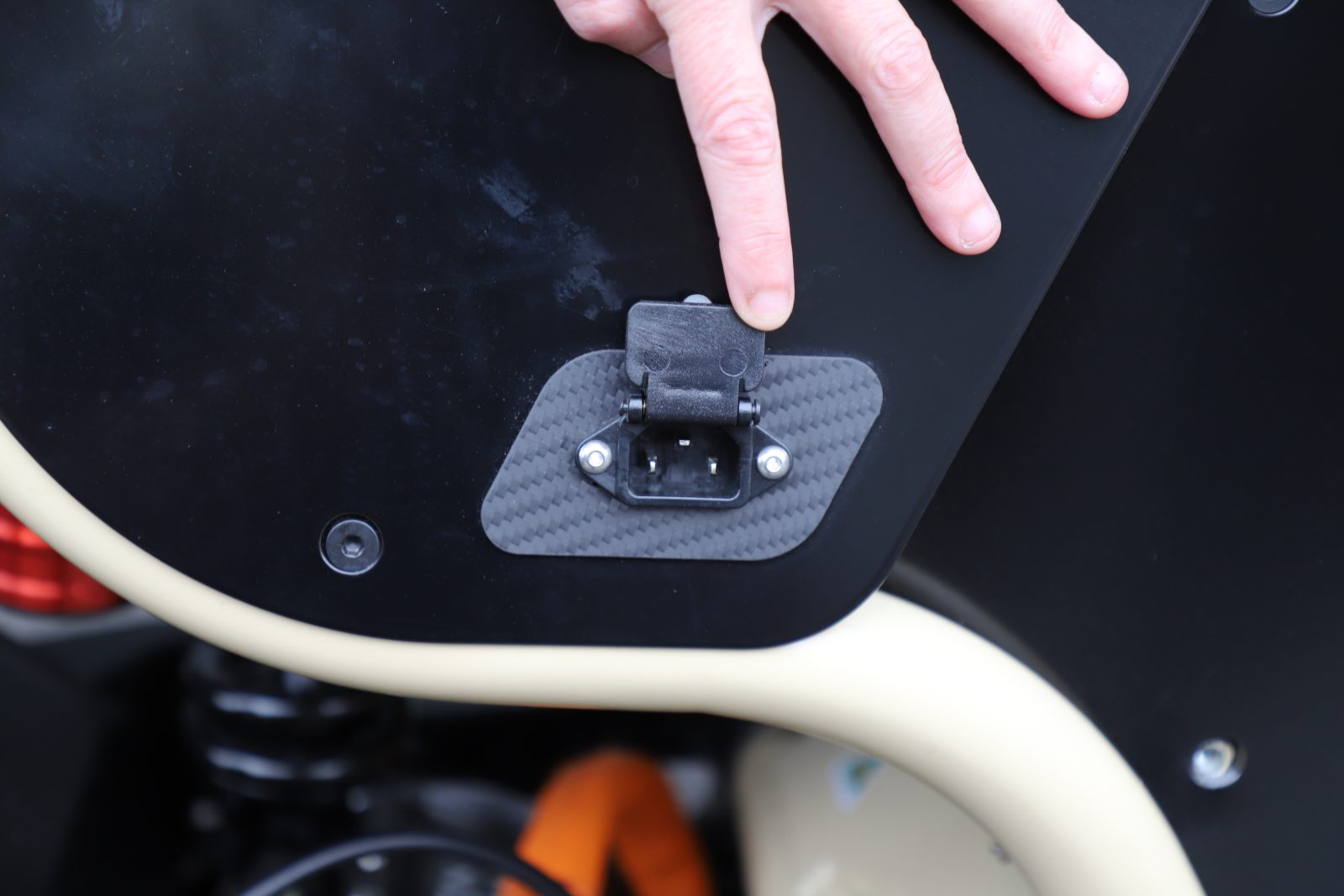

There’s a fast charger ($290) that conveniently packs up under your seat which connects the bike to the wall via an external charging point on the bike’s right-hand side panel. You can also choose to up-spec to a Level 2 charger ($1190) which is compatible with public charging stations, reducing the top-spec NKDx’s charging time down to just a couple of hours, or opt for a portable system, meaning you can lift the battery out of the bike and charge it overnight in your home or in your workplace during the day.

I reckon it’s the NKD’s unique shape that makes its seat look higher than it is, but at 815mm (there’s 770mm available, too) it’s fairly accessible for most riders. Sitting aboard the bike, you’re met with a simple LCD dash displaying your speed, a tacho, the battery level, what mode you’re in, as well as an odo and tripmeter.

At both ends of the one-piece tapered handlebar are quality-looking switchblocks set beneath those impressive mirrors, while even the master cylinders for the ’bar-mounted front and rear brakes look like anodised aluminium as opposed to the plastic units you see on almost every sub-$20k bike these days. Both the ’bar and the master cylinders are Fonz branded, too – a neat touch.

Once the ignition is on (the NKD+ and NKDx come standard with a keyless ignition), making the vehicle live is as simple as flicking up the sidestand, then it’s twist-and-bloody-go. Because despite testing all sorts of electric bikes over the years, from early Super Socos which topped out at 60km/h, right through to Lee Johnston’s Isle of Man TT Zero podium getter, the launch off the line caught me a bit off guard as the thing leapt forward and into the traffic on Melbourne’s oh-so fashionable Chapel Street.

Even though I’m prepared for it, the acceleration still impresses me and I’m searching for gaps in the traffic in order to get to the front of the queue to experience it again and again. I’m riding Michelle’s personal bike, so I’m not sure of its actual weight, but depending on spec the NKD will tip the scales somewhere between 111-132kg. Either way, the acceleration is addictive.

Both the NKD and the Arthur use a regenerative-braking system which is harnessing the energy created on deceleration and feeding it back into the battery.

Fonz has the ability to program just how much regen, or just how quickly the bike will decelerate off throttle, and it’s also activated by the initial movement of either brake lever. You’ll know when regen is occurring by the red lights that appear around the perimeter of the dashboard.

One idiosyncrasy which takes a bit of getting used to is the ADR requirement that states the motor can’t accelerate while either brake is engaged, and as someone who uses rear brake to aid the kind of manoeuvrability a busy city requires, I often found myself accelerating but being left powerless, before figuring out why and having another go. As an owner, you’d get used to it, and it wouldn’t be an issue for long.

Speaking of brakes, that’s handled by a combined braking system made up of a single disc at both ends gripped by LBN-branded calipers and, used together, they haul the bike up confidently and effectively. The combined braking system also does a good job of masking any dive in that short, non-adjustable, right-way-up fork. Instead of diving heavily under heavy front braking, the simultaneous application of the rear steadies the whole shebang and adds stability.

The rear shock has a remote preload adjuster and, while I didn’t spend enough time on the bike to really get a for its effectiveness or play with the adjustment, it certainly didn’t make itself known to me, which is a good start.

I don’t know whether it’s the Mitas MC19 dual-purpose tyres’ tread pattern, the small diameter Y-spoke wheels or if it’s the 29º rake of that unconventional front-end, but there is a slight disconnect between the handlebar and the front wheel. There’s still feedback coming through to you, just not as much as I’d probably like on a small machine designed to navigate the thrills and spills of city life. However, I suspect this would improve greatly if you ticked the Pirelli street tyre box during the purchasing process over the standard-fitment Mitas hoops.

That unconventional front-end, by the way, is the legacy of a scooter chassis – they all look like that under the plastic bodywork – and what began as a prototype starting point as the firm looked at designing its first motorcycle, was retained in the end because Michelle ended up falling for the unique styling cues it offered.

The NKD boasts plenty of other clever features, too. Like the reverse gear that’s actuated by pressing a button on the left-hand switchblock and twisting the throttle – handy for awkward parking spots – and there are two sets of footpegs, both aimed at the rider’s ergonomic preferences. The forward-mounted ’pegs are good for taller riders (or for all riders when there’s a pillion), while the mid-mounted ’pegs offer a sportier rider triangle (or pillion ’pegs) – and both were comfortable for my 164cm frame.

It’s what Michelle refers to as the “Mechano vibe. We can fit into so many people’s requirements.” And she’s right. Whether it’s price, performance, style or ergonomics, if you have a limited pool of potential customers, it makes good sense to cast your net as wide as possible. But perhaps the most clever decision of them all is to offer what Fonz calls the guaranteed trade-up offer. Having launched its first scooter in 2012, the company knows a thing or two about just how quickly the EV space is moving so will buy back your powertrain tech and batteries and upgrade you to the latest as it becomes available.

The starting price for a Fonz NKD is $11,990 (plus on-road costs) and, according to Michelle, the average purchase price is around $15k.

“Some people have specced them up to 26 grand, they’ve literally ordered every different feature and function; tick, tick, tick, tick,” she said, adding that the majority of NKD buyers are males aged between 35 and 55, are right into the technology associated with EVs and are looking to reduce their impact on the environment. Which explains why Fonz bodywork choice extends to materials as well as colour with options including recycled plastic at one end of the scale and full carbon-fibre at the other. It’s a well thought-out operation.

The NKD’s chromoly frames are manufactured on New South Wales’ Central Coast, which affords Fonz the luxury of being able to powder coat them in the customer’s choice of colour.

“Once you manufacture a frame, it needs to powder coated really quickly,” says Michelle, adding that the carbon associated with shipping such a bulky item from overseas was part of the decision to have the frames manufactured locally.

The body kits are also manufactured in Australia, as are a handful of other parts including a couple of brackets that are 3D printed in-house at Fonz’ carbon-neutral micro-factory in Sydney’s Redfern, where assembly takes place. And the result means the NKD is certified 70 percent Australian made.

Depending on spec, the batteries are supplied either by LG, CATL or Samsung and, while the brand wasn’t forthcoming with the supplier of the motor, it confirmed most of the electrical componentry is unsurprisingly sourced from Taiwan and China.

I arrived at Fonz expecting to ride an ordinary well-built electric offering, complete with all the bells and whistles your average buyer has come to expect in 2023. But what I didn’t expect was the out-of-the-box thinking that makes the NKD such a logical and cleverly executed electric commuter. Yes, the motorcyclist in me would prefer larger-diameter wheels and a more orthodox front-end, but then I think that might be missing the whole point of the NKD, which was to build a sustainable transport option that answered the very questions being asked by would-be EV adopters.

Test Kellie Buckley + Photography Janette Wilson