Cripes. Copping your first eyeful of Honda’s new supernaked contender in the flesh can be a bit of a stand back and ‘what the hell’ moment. Yes, the company has committed the odd shock-and-awe visual attack on various market niches in the past, but this is a new level. What’s going on?

It seems clan-H has decided to have a red hot go at this class and sees a future in it. That’s understandable, since a full-house sportsbike isn’t everyone’s proverbial cup of tea. Plus, these days, given our increasingly restrictive speed enforcement regime, there are times when you don’t necessarily want to be on something that screams World Superbikes.

But – and here’s the catch for a designer – that doesn’t mean you want some neutered replica of a motorcycle. Some character and a bucket-load of performance would be nice, thanks. Clearly Honda has got the message, producing what it hints at being a new-gen café racer with a respectable 106kW (143hp) on tap.

Factory PR on a model is always a little revealing on what they’re trying to achieve and, for the cynical, perhaps what medication they were on at the time. In this case, it’s fascinating that Honda came up with a new term: “Neo Sports Café Styling”. So, new sports with a café-racer influence, is that what we’re talking? Perhaps.

If you’re struggling with that concept, the company assures us: “It’s like a triple-shot of espresso for your motorcycling soul.” Actually, there’s a lot to like about that idea and, once you’ve ridden the bike, you can see where Honda’s coming from.

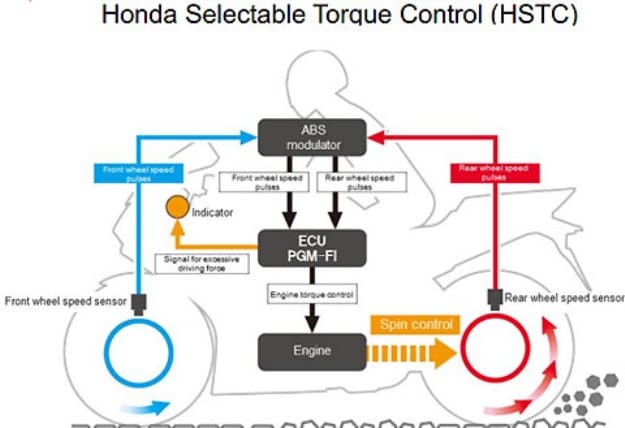

The bones of this machine are effectively new, though you can see shadows of its forebear in the mix. It’s the first time we’ve seen this frame. Like its predecessor, there’s a fairly simple steel backbone design that arches over the powerplant, but the form is different and Honda says it’s been on a significant diet, losing 2.5kg.

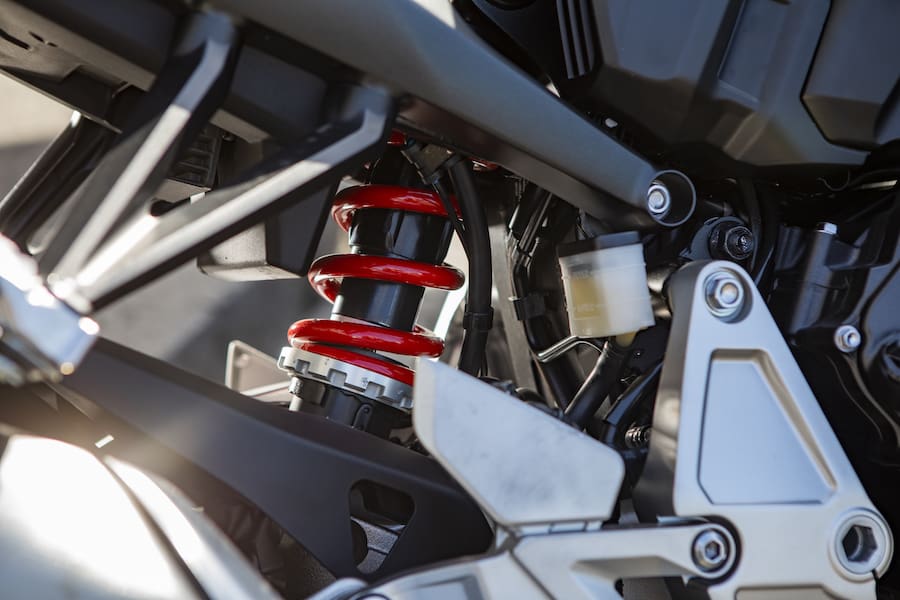

By far the most dramatic component of the chassis is the aluminium single-sided swingarm. Traditionally this isn’t a weight-saving measure, but it looks sexy and has long been a Honda signature, going way back to the 1987 RC30. That’s hosting a slightly wider rear tyre by the way, a 190 section.

You cop high-end Showa suspension at each end. Up front is a Separate Function Big Piston fork with full adjustment for spring preload plus compression and rebound damping – the latter is restricted to one side. The rear unit also runs the full range of adjustment.

Braking is by Tokico, running 310mm discs and four-pot calipers up front, with a 265mm disc on the rear. That lot is modulated with a two-channel ABS system.

Put the chassis package together and what you have is a motorcycle that’s a little longer in the wheelbase – by 10mm at 1455 – and running fairly conventional steering geometry for a sporty street bike at 25 degrees of rake and 100mm of trail.

And the engine? It’s a development of the previous-gen CB1000R powerplant, which in turn was a variant of the 2007 Fireblade’s engine. The bore and stroke are a give-away, remaining at 75 x 56.5mm – different to the current ’Blade.

What Honda has done is bump up the compression a little (11.6:1) and used forged rather than cast pistons. It’s also increased the valve lift, altered the combustion chambers and is running a much larger throttle body size at 44mm.

The engineers reckon this has given a boost in outright power and torque numbers, while still being tuned to deliver a solid midrange whack at around 6000-8000rpm. Redline starts at 11,500rpm with the electronics cutting in at 12,000.

As for creature comforts, the overall aim has been a more relaxed ride position, with the tapered handlebar raised by a substantial 13mm and made wider by 12. The downside is the seat height has gone up 5mm to 830mm – not ideal for shorter riders, but the weight has dropped substantially by 12kg (to a claimed 212kg wet) as some sort of compensation.

There is pillion accommodation, but it’s token. This really is a solo Sunday toy and Honda will very happily sell you a better two-up proposition.

Instrumentation and electronic indicators are all in the one more or less rectangular unit, with a round tacho, numeral speedo, gear indicator, multi-function trip meter, clock, mode readouts and assorted warning lamps.

One thing you will notice as you go over the machine is the fairly high-end finish. Honda happily highlights that it has a total of six exterior plastic panels. That may seem like a lot, but on a busy design like this, it’s not. Instead there is a lot of brushed metal finish, such as the radiator surround.

There are numerous touches that would make an owner feel pretty good, take the multi-component headlight for example. It’s running an LED ring and twin bar elements in the lamp itself. That design theme is reflected by the tail lamp.

As with a lot of motorcycles, the photos don’t always do the CB justice. Once you get over the fact that it’s a fairly wild looking piece of kit – and it has a Honda badge on it – you realise the whole thing comes together really well as a visual package. On board, little touches like the tapered handlebars add to the appeal.

Swing a leg over the thing and you’re struck by two things – the seat is a fair way off the deck, but the bike overall looks and feels light and narrow, particularly for a litre-class four.

With injection taking care of the engine feeding, and a fly-by-wire throttle, the powerplant behaves pretty much as you’d expect on start-up. It self-monitors for temp and runs a high warm-up idle until things settle down.

You have three preset riding modes to play with: rain, standard, sport. There’s also the option of setting your own custom combination. Around town, standard works pretty well, without the thing being freakishly sensitive to the throttle, while the other two work pretty much as advertised.

There’s no doubt this is a very strong and responsive piece of kit. It feels relatively low geared – more so in Sport mode, which alters the response when you’re running the first three cogs. Really, the acceleration off the line is sensational.

That whole push-your-eyeballs-back-into-your-head sensation continues pretty much through the rev range. However it’s the low and mid ranges that really impress. By the time you hit the upper end of the ‘fat’ part of the delivery curve – 9000rpm – you’re quite ready to pick up another cog. Sure, it makes more noise and power at the higher end of the ranges, but 99 percent of the time it all seems a little pointless and cruel. Short-shifting by nine more than does the job.

When you’re not exploring the CB’s considerable abilities, and are just bumbling around town, you can be ultra-slack on the gears. In most situations, you could be using any one of a few cogs and get the job done.

If there’s a glitch at all in the power delivery, it’s that the bike can tend to ‘hunt’ just a little at low and steady throttle openings. This is noticeable if you’re in sport mode rather than standard. It’s subtle and I’m not sure even rates as a complaint. The action of the slipper clutch is light and friendly, with a decent take-up band. In fact, this is the one of the few low-tech things on the handlebar, as it’s cable-operated.

Clearly you have a lot of room for customisation on the suspension, but the stock settings are pretty close to the mark for general use. You’ll probably want to play a little for your size and weight, but if you rode it out of the box it would be fine for most.

Setting it up for a track would be an entertaining exercise. Lack of wind protection aside, it has a lot of potential in that area and could be an absolute ball on a ride day. There’s meaningful adjustment available, so a little patience would be rewarded.

Braking is strong, with good feel, and really there are no complaints. It’s not difficult to get the thing standing on its nose, and you soon get accustomed to relying heavily on the front end.

Stock rubber on our example was Dunlop Sportmax 214, which is a sports-touring design that was fine in the dry while we had the bike. It stubbornly refused to rain during the test. That said, I’d be sorely tempted to fit premium sports rubber the moment the stockers looked tired. The CB has huge performance potential and you’d be a bit more secure on something higher spec, even if it punished the wallet.

As a package, this thing is a delight to play with through a set of turns. It’s pretty well vice-free, and extremely difficult to upset in any serious way. There’s enough suspension travel to cope with our less than perfect roads.

Steering is light. The tip-in is reasonably quick and entirely predictable, while mid-corner adjustments aren’t an issue. Combine that with a very willing powerplant with a broad spread of urge, plus decent brakes, and you have a very capable bit of gear. Really, despite its urban warrior looks, it’s actually a very capable sportsbike. Find the right environment and I’ve no doubt it’s very good at bringing out the inner stunt monkey as well…

One thing that becomes addictive is the throaty rasp of the exhaust as you pick up revs. The note changes around 5000-6000, giving the thing a bit of aural character.

You can spend a day on it in reasonable comfort as it has a halfway rational ride position and the facility is there to get the suspension right for longer stretches. It’s hardly a tourer, but one person can sling a bag on the rear perch and head for the sunset with no real dramas.

Fuel consumption is claimed to be around the 6L/100km mark, which seems about right. Think seven or eight if you’re hammering it, though I was getting around six and nudged the 5L/100km mark once, and you have a little over 16lt to play with. That’s not generous, but easy to juggle on a longer journey.

So how does it shape up as a proposition? Really, it’s the $16,499 (plus on-road costs) price that helps set the tone for this model, putting it well and truly in amongst its competitors when it comes to delivering bang per buck. I reckon it’s a thoroughly enjoyable bit of kit in its own right, with a generous dose of ratbag and some decent sport ability on a tight bit of tar.

The triple shot espresso is well worth a look…

The executive suite

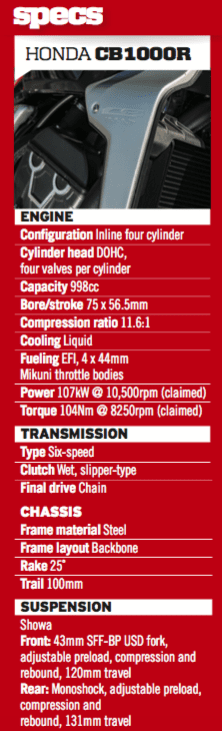

It seems you can’t buy a high-end motorcycle these days without a suite of electronics that truly boggles the mind of anyone who hasn’t kept up with this stuff. There is of course the safety net factory, primarily ABS.

Honda is also pretty keen on what it calls Honda Selectable Torque Control (HTSC), which effectively helps dictate how loose (or not) you want the motorcycle to get. At maximum intervention, there are no skids and none of that wheelie nonsense. From there you can have your misbehavior in degrees.

And of course we have to have selectable modes. In this case it varies how the machine responds according to preset parameters, altering the engine tuning, throttle response and how it behaves in individual gears. Essentially they ‘talk’ across the motorcycle’s electronics.

In the case there are three presets; Rain, Standard and Sport, where the HSV|BC||||TC, power output and engine braking all get together to deliver you the best package for the conditions. Okay, there’s a fourth option. Well, you can also create a setting according to your own peculiar tastes. There are three options offered for each parameter and you can save it for future rides.

The last trick worth mentioning is what I like to think of as the mood lamp on the side of the instrument cluster. You can set it to flash white past a pre-set rpm level, and then it can change to yellow then amber then pink as a reminder to change up. It can also operate as a riding mode indicator.

The competition

This has become an incredibly busy space over recent years. Not so long ago, most manufacturers felt obliged to have a litre-class naked on the books. The effort they put in varied, but really there were times when the offerings were a bit of a yawn-fest. There were lots pleasant and powerful-enough bikes, sometimes with handling that got decidedly unruly when really pressing on.

However some subtle shifts in the market has seen this segment become a real battleground and we’re seeing a very long list of players, often with very real sporting credentials. At the upper end of the price bracket, you have seriously fast objects like BMW’s S 1000 R with a 123kW (165hp) power claim and a price tag that’s a few grand north of where the Honda sits.

Similarly Yamaha’s MT-10 boasts around 10 horses over the Honda, but comes at a price premium. Really, where this bike sits comfortably is in direct competition with Triumph’s Speed Triple, Suzuki’s GSX-S1000 and Kawasaki’s Z1000. In that pack, it’s a very formidable competitor.

TEST GUY ALLEN PHOTOGRAPHY BEN GALLI