Mike Hailwood is widely known as one of the top five grand prix racers of all time. He is also widely known as being capable of riding any type of machine in any condition. Sound familiar?

He was a naturally gifted rider but his colossal skills didn’t involve being a development rider. He simply rode and won on what was provided, making minor adjustments and never complaining about the deficiencies any of his machines might have had.

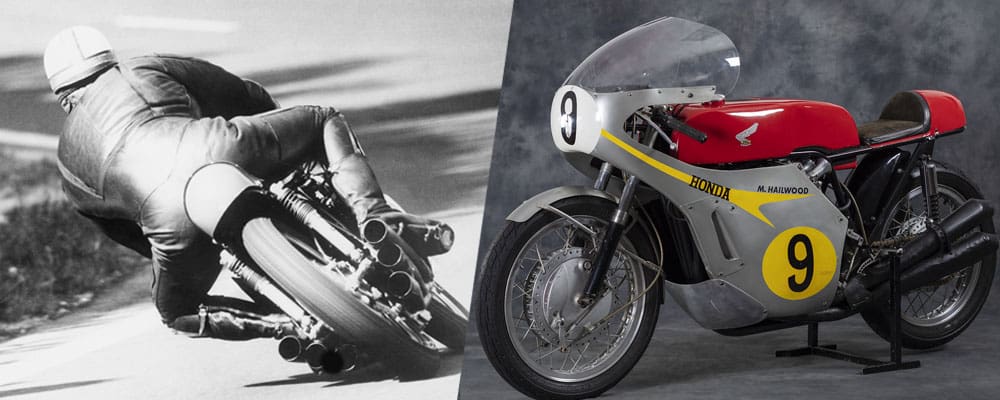

One motorcycle was the exception: Honda’s 1967 500cc four-cylinder RC181. This was a crucial time for the Japanese giant. From 1959 to 1966 it had gone from a tentative GP entry to dominating the sport. That year it won the manufacturer’s title in all five classes, along with riders’ championships in three of those.

It also had Mike Hailwood on its payroll. In 1966 he won the 250cc class with half a season of races to spare, beat MV’s Giacomo Agostini to the 350cc title but had to play second fiddle in the 500cc championship to the only rider considered his true equal.

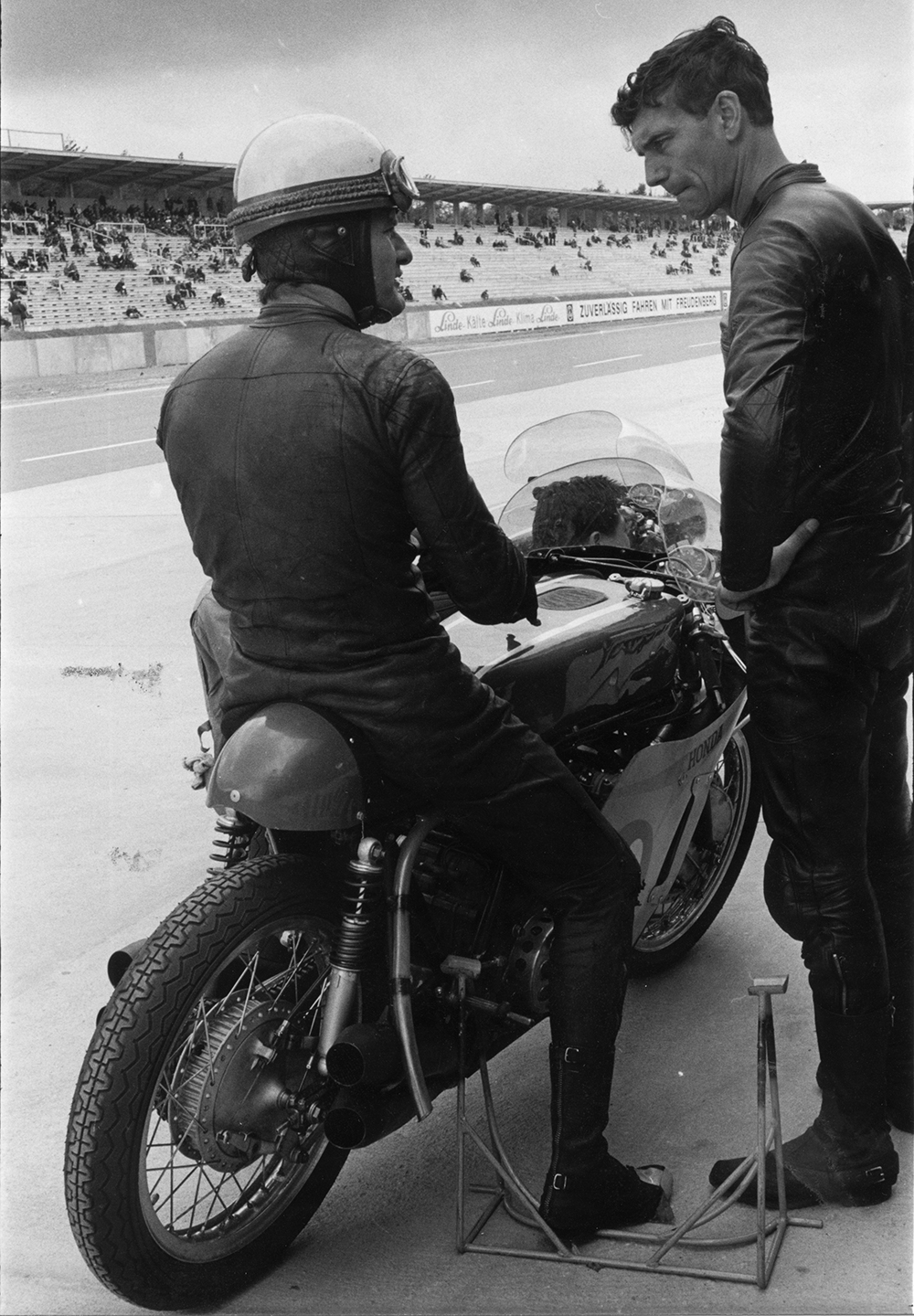

Ago’s MV and Hailwood’s Honda were the pinnacle of 1960s 500cc multi-cylinder four-stroke design. The world’s two best riders took their MV-Honda duel in the 500cc class to new heights in 1967. Their Isle of Man TT battle that year was a classic. Hailwood’s narrow win over Ago was also accompanied by a lap record that would stand well into the next decade.

The rest of the season was no less exciting with the pair ending on equal points and the same number of race victories (five each). With more minor podium placings, Ago was declared the champion.

Hailwood was signed up for 1968 but Honda suddenly announced its withdrawal from GP racing entirely just before the season started. It would stay away from GPs for nearly 10 years. This was a bizarre situation for both the world sport and Hailwood, who would end up being paid big bucks not to race in Grands Prix. Imagine Honda doing that to Marc Marquez today?

Meanwhile, in anticipation of taking the elusive 500cc crown for Honda in 1968 (a feat it didn’t achieve until nearly 20 years later), Hailwood had already stepped outside the square of convention.

Late in 1967 he commissioned fellow Brit Ken Sprayson to build his own version of Honda’s legendary four-cylinder 500. It was almost a winner first-time out and became one of GP’s greatest ‘could-have-been’ stories.

The go-to guy

You wouldn’t think one man working alone could improve on what a team of factory technicians had spent years developing. However Sprayson had a remarkable talent for lateral thinking and had long been the go-to man for racers and teams alike. His work had helped others win at the highest level and on the world’s toughest race tracks, including the Isle of Man.

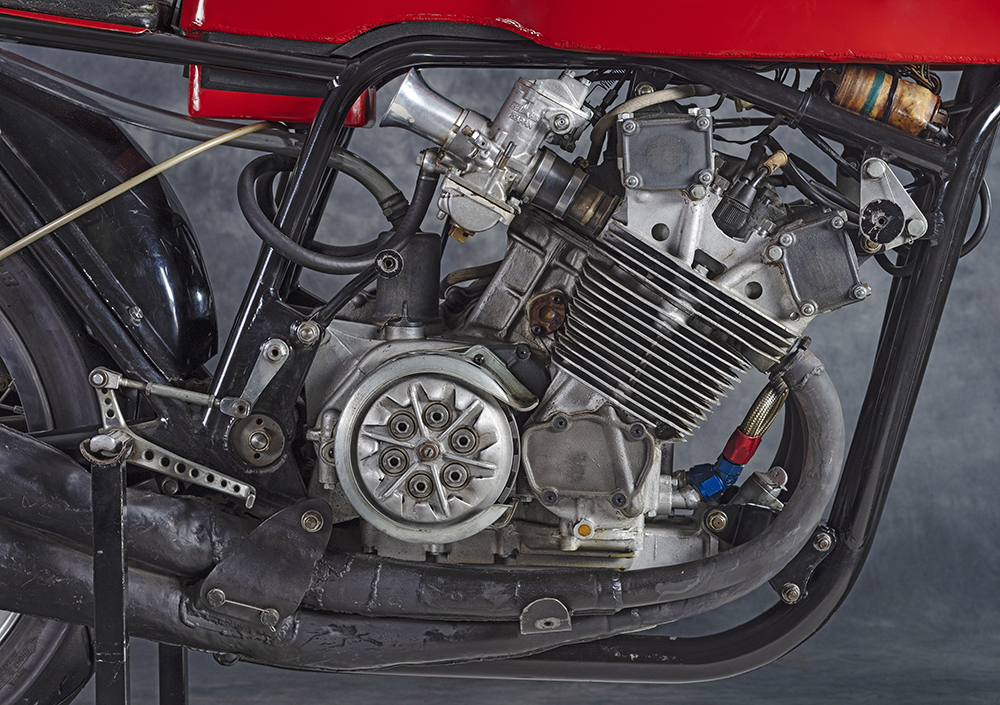

Sprayson was convinced the Honda’s handling deficiencies were due to the factory frame omitting the bottom cradle to allow the engine to sit lower, improving the racer’s centre of gravity.

This meant the engine was essentially a stressed member of the frame, a virtually untried concept at the time. Honda had used this feature as far back as its first TT racer of 1959 but its 500cc racers only appeared in the mid-1960s. Was the engine overpowering the frame?

Vincent had used its huge V-twin engine as a stressed member as far back as the mid-1940s. But the structure connecting its steering head and rear suspension was a sturdy boxed-steel section large enough to double as an oil tank.

By comparison, the Honda design relied on tubing, nuts and bolts. This combination gave the potential for flex, especially with an engine producing over 90 horsepower. Add in the skinny tyres and low-spec suspension of that era and it’s easy to see how the envelope was being pushed way too far.

Sprayson’s solution sounded simple: Reinstate the bottom frame rails. However the execution of this was a major challenge as a lot of components got in the way. The engine had a deep sump, so how could it be kept low in the frame and as far forward as possible while retaining good ground clearance? Then there were the four exhaust pipes to contend with, along with the engine drain plug at the rear of the crankcases. The final issue was building a structure that didn’t foul the drive chain.

Pencil and paper

In the 1960s industrial design was still being undertaken using graph paper and graphite pencils. In this pre-computer age Sprayson literally sketched various designs with pencil and paper, rubbing out the lines that didn’t work. He then drew a full-sized blueprint on a large piece of cardboard before actually constructing the final version in metal.

“I suppose the actual building of the frame took me a fortnight but it took me a lot longer to establish a design,” he told a prominent UK motorcycle newspaper reporter. In a detailed description of his project to that publication he revealed his true thoughts about the original Honda frame, describing it as “an attachment” that would never work in the way its designers intended.

“However firm a bolted-up joint may be, you will always get some movement in it,” he said referring to Honda deleting crucial parts of the frame and using the engine as the mainstay support for the chassis. “The more exotic the engine, the greater the problem.”

He also revealed why he had to start from scratch.

“You cannot just take an established frame and alter it to take an engine such as this,” he said. “You have to start with a clean sheet of paper.”

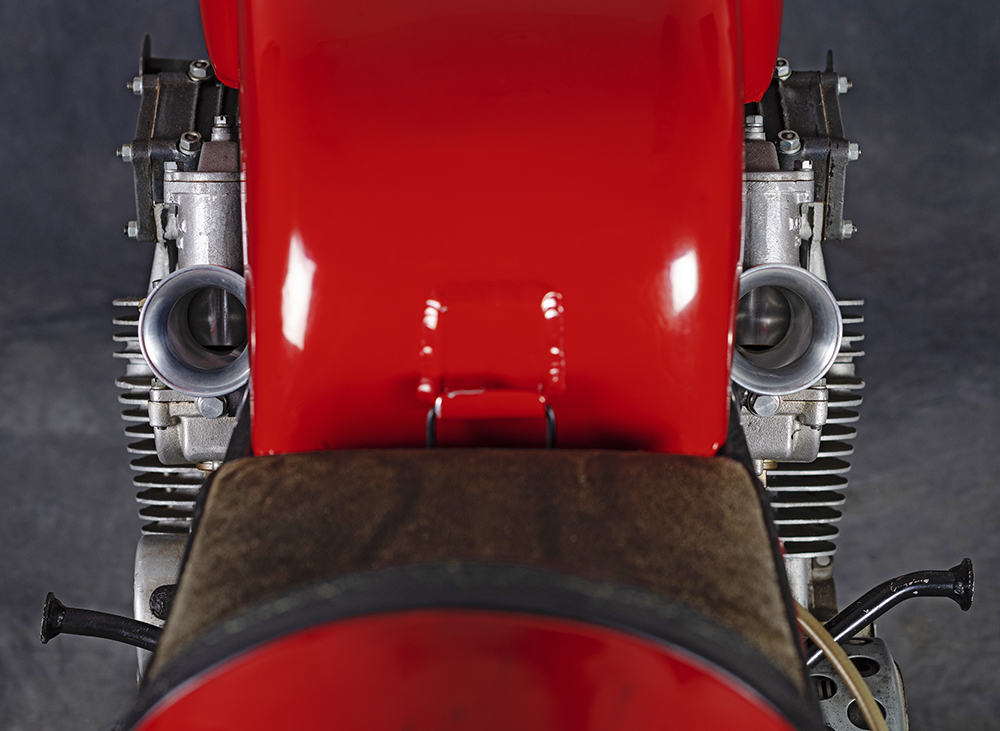

Sprayson’s design was clever but complicated. A large-diameter single tube, rather than a double cradle, ran under the centre of the engine. This kept the chassis narrow while allowing room for the four exhaust pipes to snake back in their tuned length.

A strong sub-assembly of tubing created space to access the sump drain plug. A heavily-braced steel section contained the swingarm pivot and connected the rear engine mounts. The idea here was to concentrate strength at a critical area so the stresses of acceleration wouldn’t allow the frame to twist.

Tube bracing in other important areas, such as around the steering head, meant the frame had a lot more metal than the factory version. However, it weighed just 22lbs (10kg). The material used was Renolds 531 tubing, most commonly used in the aircraft industry and F1 car racing.

Of course, rebuilding the Honda from the ground up gave Sprayson and his small team some more problems. Hailwood wanted it to look as much like the factory racer as possible but, apart from the forks and wheels, many vital components wouldn’t fit.

How to get around this problem was solved by England’s cottage industry, and a number of motorcycle component manufacturers quickly came to the rescue.

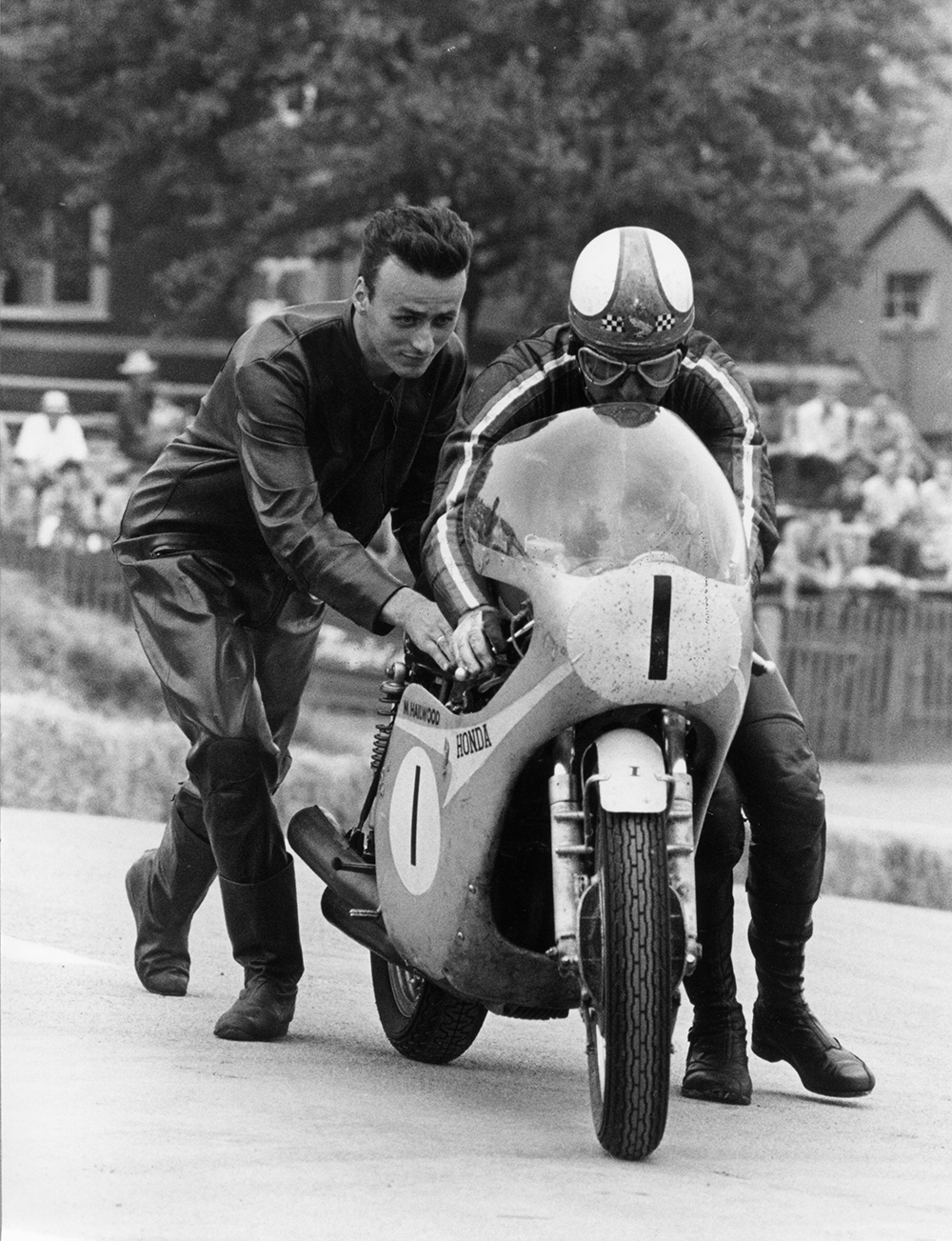

For example, one company provided the unique petrol tank, another the seat and fairing. Ace Honda mechanic Nobby Clarke was hired to turn the collection of parts into a running racer. He pulled one of his all-nighters to complete the assembly but there was no opportunity for even a brief test before Hailwood and the bike were off to Italy for their first race.

Baptism of fire

It may have been a non-GP-championship meeting, but the late-March event at Rimini had none less than Giacomo Agostini entered. Hailwood’s ability to just jump on a motorcycle and win was put to the ultimate test that day.

The Honda was fuelled up, fired up and then handed over to Mike the Bike for the first time. What happened next was simply amazing. Hailwood led Ago and his well-developed MV on his untested Honda hybrid before running off the track briefly then rejoining and charging back to finish second. He then won the next Italian event at Imola and was confident of a great season ahead.

But Honda’s withdrawal from GP racing left him in limbo, especially as he was being paid the equivalent of millions of dollars in today’s monetary value not to race. So the Honda was seen briefly in a few more non-championship events before ending up as a museum piece.

Today it is owned by Californian collector and classic-racing enthusiast Virgil Elings, founder and owner of the Solang Vintage Motorcycle Museum, just north of Santa Barbara. Elings had it restored in the early 2000s by New Zealand technician and Manx Norton specialist Ken McIntosh.

Fortunately, having been raced so little, this ultra-rare Honda was amazingly intact. However, bringing it back to life was a huge achievement that involved minimal compromises to originality. The most obvious is the switch to aluminium carburetors as the priceless magnesium originals disappeared in the 1970s.

To stand and look at this racer transports the viewer back to an era of motorsport where everything appeared simpler than today. Then you look closer and understand the extent of human endeavour, both technical and physical, expended on a one-off racing project such as this.

WORDS HAMISH COOPER PHOTOGRAPHY PHIL AYNSLEY