Can a standard production electric bike, one that can be ridden legally on the road, take on the hardest racetrack in the world? We didn’t know, but last year we set a goal to be the first team to ever race just such a bike in the TT. We knew it was crazy, but from the showroom to Snaefell might just be possible, and we wanted to find out.

In 2009, Rob Barber won the first all-electric race to be held at the TT, with a winning lap time of 25m53.50s, averaging 87.434mph. What was then called the TTXGP has now morphed into the TT Zero, and the lap times have tumbled. John McGuinness currently holds the lap record at 18m58.743s, averaging 119.279mph, set in 2015 on a Mugen. Top speeds are now approaching 160mph, with William Dunlop reaching 159.8mph in 2016 on the Victory RR race bike.

Japanese giant Mugen spend millions on its TT Zero preparation. Its bikes are the most expensive and by far the most advanced racing at the Isle of Man, and there was no way we were going to give Bruce Anstey or Guy Martin a run for their money. But maybe, just maybe, we would be able to get close to Barber’s 2009 winning time. If not, the late Mark Buckley finished third that year with a time of 30m02.64s, averaging 75.350mph, and there was a bloody good chance we could match that.

Averaging more than 120km/h around the TT may not sound that challenging, but remember our bike was road legal, not some swish prototype with a throw-away battery. Yes, we intended to hit well over 220km/h through villages and towns, clipping kerbs and brushing walls on a 258kg roadbike – yet, after a 30-minute recharge, the thing could still be ridden home after the race.

The Energica Ego has no gears, a twist-and-go throttle, and the thing is so heavy, the company even fits it with a reverse gear. We didn’t know how it was going to cope with the TT course’s notorious bumps and jumps, and had no idea what Kirk Michael was going to be like at 240km/h. I was massively out of my comfort zone.

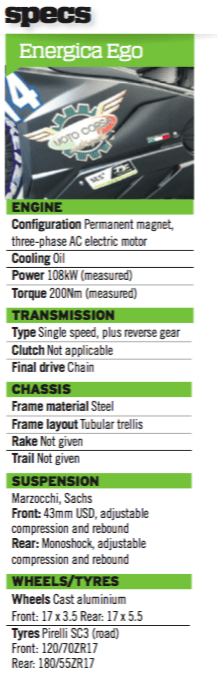

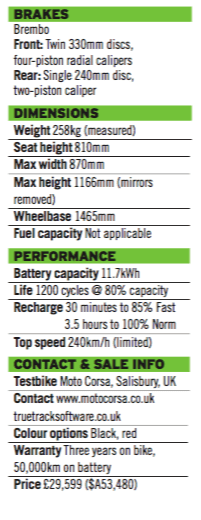

The Ego has a quoted top speed of 240km/h, and claimed motor outputs of 108kW (145hp) and 200Nm. It has fully adjustable suspension and Brembo brakes, optional power modes and four levels of engine braking, which also helps to recharge the battery when you’re off the throttle.

Here in the UK, you can walk into a dealership, hand over £29,599 (AU$53,480) and ride away on the same bike we were about to punt around the Mountain Course.

With no clutch, no gears and no engine noise, testing felt distinctly alien, and I never realised just how noisy knee-sliders are when they come into contact with the track!

Initially I rode the Energica like a normal bike, getting 100 per cent throttle wherever possible, jumping on the brakes, turning, hitting the apex and jumping back on the power again.

Acceleration is seamless – gearless and impressive – but hard riding vastly reduces battery life. Simply put, we’d never be able to complete the TT Zero’s 37.7-mile (60.7km)distance if we rode flat out.

I needed a more calculated, mature approach – to stay tucked in for longer and be as aerodynamic as possible. The key, I eventually worked out, was smoothness, high corner speed and momentum.

We wanted to keep the Energica Ego as standard as possible. As there’s no oil in the motor or a sump, we didn’t need to lockwire a sump plug or fit a regular catch tank because there aren’t any fluids. We needed to fit an emergency stop button, for safety, and replace the standard Pirelli tyres with stickier rubber, but otherwise it was bog-stock standard.

We could adjust the suspension, gearing and tyre pressures, even try different compounds, but

only once we’d completed our first practice lap. We didn’t know how it was going to cope with the demanding track. We didn’t know how much the famous mountain was going to draw out of the battery. Nobody had any race data available, as nobody had ever raced a standard production electric bike around the TT. What we did know was that, if everything came together, we’d be creating a bit of motorcycling history.

Our first and most important goal was to qualify. Then, fingers crossed, complete the one-lap race. That done, we planned to go to the pub.

Less than a week earlier, I’d ridden our standard Energica Ego roadbike into the TT scrutineering bay and said: “We want to race this, please.” The technical officials looked a little bemused, but to their credit applauded the idea, even offering tips on how to make the bike race-ready.

This left us only a few hours to get the Ego prepared for that evening’s practice session. It was all hands on deck as TT privateer Dave Hewson and his willing team helped to convert the roady into a racer. We removed the headlights, mirrors, number plate, sidestand and indicators. We also made and fitted a shark’s fin, which sits just in front of the rear sprocket, plus a small catch tank (the motor is oil-cooled). While we fitted the catch tank, we also lockwired a few parts and triple-checked everything.

We’d already fitted the required emergency stop button and Metzeler race rubber, and the bike breezed through scrutineering at the first attempt. Up on its stands and wearing race numbers, it didn’t look too out of place in the paddock, either. In fact it turned more than a few heads.

The organisers came over to inform us we would start last for the first practice session, which suited us fine because we didn’t even know if the Ego would complete the single lap.

No matter what bike you’re riding, there’s no getting away from the dangers of the TT. The light poles, stone walls and houses don’t bend or hurt any less just because you’re on an electric bike. And the 190km/h entry into the village of Kirk Michael still takes absolute concentration, especially as the Energica Ego weighs 258kg – that’s as much as a BMW R 1200 GS in full touring spec!

On the start line I saw Kiwi legend Bruce Anstey, who was chasing the first 120mph electric lap on the Mugen Shinden Go, and Guy Martin on the sister Mugen, followed by TT winner Dean Harrison on the beautiful Sarolea. I was in good company.

Tension was building as we inched to the line. There was no turning back.

As I threw a leg over the almost-silent Ego for my first practice run, I could hear the crowd and even the commentary.

“Go on Chad!” shouted injured TT legend John McGuinness, who was waving from the side of the road. Up to the line I was now just 10 seconds away, waiting for the final tap on my shoulder signalling my launch to plunge down Bray Hill. Oh, my god!

Riding the TT is hard enough, especially the first few miles where you have to recalibrate your brain to the sheer speed of it, use both sides of the road and convince yourself no cars are coming the other way. Add the new-to-me silence of an electric bike – as well as the complications of having to monitor and adjust your riding according to the battery power available – and the task is even harder.

There’s a percentage readout on the Ego’s full-colour dash that informed me how much charge was left in the battery and allowed me to work out how much I needed to complete the lap. I felt like Archimedes, furiously calculating battery percentage against miles completed, while also trying to ride a fast lap.

I needed 50 per cent battery to get over the Mountain, which meant I needed over 60 per cent in the bank by the time I got to Ballaugh Bridge and 55 per cent at the end of Sulby Straight. After the 32nd milestone it was all downhill, which meant I only needed 20 per cent to get down off the Mountain and over the finish line.

Thankfully, the Energica performed admirably. The Brembo brakes were more than strong enough and fade-free; all those 258 kilos were noticeable during fast changes of direction – but never overwhelming; and stability was perfect, even through the notoriously bumpy section from Ginger Hall to Ramsey.

After weeks of wondering if the Ego could do it, I found myself at Creg-ny-baa with 25 per cent charge and it was then I knew we’d be home safe. As I crossed the line for the first time my makeshift team cheered from pit wall, which made me a little emotional.

Only three bikes completed a lap: our road-going Ego and the two Mugens ridden by Anstey and Martin. As we all parked up together, the TT stars couldn’t resist coming over for a look.

We’d set a mark of 74.79mph – the first ever lap of the TT course by a production electric bike. The following night, we lapped at 79.63mph and then 80.72mph on the third lap of practice. Our best lap would have placed the Ego second in that first electric TT in 2009.

Practice had gone well, but now it was time to put our race lap together. I caught Matthew Rees on the University of Bath bike early in the lap, but knew I needed retirements to be able to move up the leader board.

Through Ginger Hall the Ego sounded terrible, as the lack of engine noise meant I could hear the suspension, the chain and sprockets, and even the pads on their discs sounded like they were moaning and groaning. It sounded like the bike was falling apart.

As I exited Parliament Square, I got a pit board from James Hillier’s team – 7th position plus 14 seconds. I just needed to bring her home.

With my head in battery-conservation mode, I was probably a little too steady over the Mountain when I should have been pushing for a fast lap time.

On the exit of the Creg-ny-baa, I beeped the horn and waved to the crowd because I knew I was nearly home. On the exit of the final corner the marshals and the crowd waved too.

It was a special moment as I crossed the line of what’s probably the toughest road race in the world, on a bog-stock standard electric bike. I ended up finishing in seventh place from nine starters, with an average speed of 78.848mph. I clocked 100.47mph (161km/h) through the speed trap and saw the chequered flag with 17 per cent battery left.

The Ego and I will probably never be winners, but on the Isle of Man one year ago we made a little bit of TT history.

Words Adam Child

Photography Stephen Davison & MCN