The Australian Tourist Trophy was once this country’s premier motorcycling event, with close links to the more famous TT in the Irish Sea, and was similarly run on public road circuits, the bigger and faster the better.

But the Australian TT – also the official national championship, allocated to a different state each year on a rotational basis – endured a troubled existence after the halcyon days when most racers here had but one ambition, to get to the Isle of Man for either the TT or the Manx Grand Prix.

As the fast and challenging closed-roads circuits that exemplified the TT spirit disappeared, the once highly prestigious event suffered the ignominy of having to be held at pocket-handkerchief venues like Melbourne’s Calder Park.

The Australian TT reached its nadir one blistering hot day in 1976 at Laverton Air Force Base west of Melbourne, where a cavalcade of international stars jetted in – and the promoter jetted out with the gate takings.

On paper, this was the event to relaunch our TT. The setting, while not ideal, was at least big and fast, with plenty of runways and side roads with which to form a 5.3km circuit. And the promoters had signed no fewer than nine top Italian racers, including Giacomo Agostini. There were works Aermacchis for Walter Villa and Gianfranco Bonera, and works Morbidellis for Pier-Paulo Bianchi, plus a dozen new four-cylinder RG500 Suzukis for the leading Australian and New Zealand riders.

An avalanche of publicity saw a huge spectator turnout (particularly from Melbourne’s Italian community) and the event was deemed worthy of having Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser on hand to present the trophies. Federal Minister for Sport and former racer Tony Street even reeled off a few laps on Kel Carruthers’ 250cc four-cylinder Honda.

It was a brilliant (if stinking hot) day of racing, highlighted by the shock of Kenny Blake defeating Agostini’s all-conquering MV Agusta, but less than 24 hours later the promoters went into receivership. Transport companies responsible for returning the overseas bikes impounded them pending payment, the international motorcycling press went ballistic and an outraged FIM threatened Australia’s controlling body, the Auto Cycle Council, with expulsion. It would be another 17 years before another TT was staged.

Although street circuits in Western Australian struggled on into the 1970s, and three events were held on the streets of Macarthur, an ACT housing estate still to be built, by the mid-1990s it seemed the days of racing on public roads were over. But then a Sydney promotions company began to consider the possibilities of re-establishing the Australian TT.

Forcefield Promotions was a Sydney-based company with a long history in motor sport. Under managing director Vincent Tesoriero, Forcefield had in 1974 launched the highly successful Mr Motocross, a series that grew exponentially to eclipse even the official national titles in importance and prestige, making household names of Stephen Gall, Anthony Gunter, Craig Dack and Jeff Leisk.

When Mr Motocross wound up in 1988, Forcefield took on the Bathurst 12 Hour production car race at Mount Panorama. After a couple of years of mediocre crowds at the Easter meeting, motorcycles were brought back to the famed track as a support to the car race in 1992, then a year later Forcefield revived the Australian TT title for the first time since the Laverton debacle in 1976.

The TT revival was short-lived, though, because following the 1994 event at Bathurst (won by Shawn Giles) the 12 Hour shifted from Bathurst to Eastern Creek under a new promoter and the bikes went nowhere.

Forcefield was again without a signature event to promote, but the revival of the Australian TT had whetted its appetite. What wasn’t an option was promoting the TT at an existing circuit, which in the case of NSW amounted to Eastern Creek or Oran Park.

And so began a number of exploratory expeditions and discussions with various councils and commercial bodies about staging a motorcycle race on public roads, with the stated aim to achieve what the original TT had done – to focus attention on a destination in the name of tourism.

In these discussions, Tesoriero explained that the TT would need the unequivocal support of the local community, including the police and local government, and of course roads that could be closed without unduly inconveniencing the public.

The talks moved around the state, from Newcastle in the north to the South Coast and west to Goulburn, but gradually the Illawarra region became the favoured option, due in no small measure to the enthusiasm and influence of the editor of the Wollongong Mercury newspaper, Nick Hartgerink.

Hartgerink had acted as PR man for local hero Wayne Gardner through most of his GP career, and was a true enthusiast. Moreover, he was a realist and, while he could see the benefits to the Illawarra region, he didn’t underestimate the hold exerted by unions in this industrial city.

While Forcefield assembled a working party to determine whether such an event could be financially viable, Hartgerink identified a seemingly ideal site for a track at Port Kembla, a steel town about 90km south of Sydney.

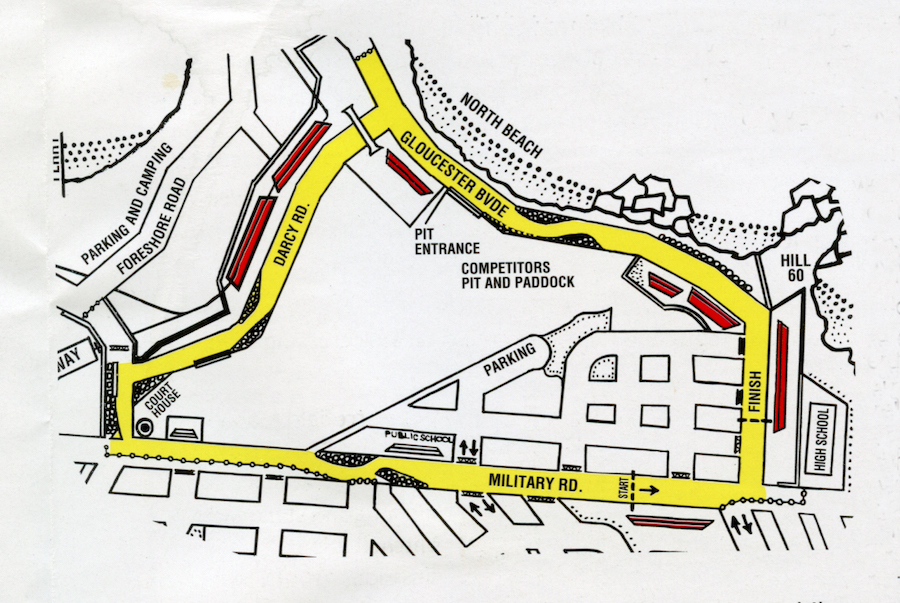

Slightly to the south of the steelworks lay a somewhat rundown industrial area with a residential section at the far southern end. A large park was opposite the houses, while on the eastern side the road ran alongside North Beach. The lap measured 4.1km with plenty of gradient changes, the ocean provided a scenic backdrop, and there was ample space in the industrial areas to set up the pits, paddock and race control.

If ever an area needed an image boost it was Port Kembla. With high unemployment, continual industrial strife, rampant violence and alcohol and drug problems, Port Kembla needed a reason to feel proud of itself again, or so the various parties (strongly championed by the Port Kembla Chamber of Commerce) reasoned when the initial meeting took place with Wollongong City Council, under Lord Mayor David Campbell.

Many more meetings followed, most with a positive result and a willingness to progress the concept into reality. A date was even set – the Australia Day long weekend of 27-28 January 1996 – but as fast as one issue was resolved, another hurdle appeared.

While local residents by and large supported the project, a small but vocal minority objected on the grounds of disruption and noise. Because the event was a national title, it came under the jurisdiction of Motorcycling Australia rather than the newly formed Motorcycling NSW, and strict (and costly) conditions were imposed to ensure safety for spectators and competitors. The local police (whose headquarters lay inside the circuit on what was to become known as Court House Corner) also played hard, insisting that spectators, apart from residents inside the track, be confined to the southern end of Military Road and within the grounds of Port Kembla High School in Gloucester Road. And local media chose to trot out file footage of the Bathurst ‘riots’ of the ’80s whenever it felt the pot needed stirring.

These issues were progressively addressed by the promoter, but the elephant in the room turned out to the omnipotent South Coast Labour Council (SCLC), under the control of the fiery Paul Matters.

While all the brouhaha was going on behind closed doors, enthusiasm for the event was skyrocketing elsewhere. Within weeks of the official announcement, every motel and hotel room for miles was booked, campgrounds filled to capacity, and private houses leased.

In October 1995, Wollongong Council’s Planning and Community Services committee recommended council approve the TT, subject to the organisers complying with provisions for spectator safety, resident access and emergency issues. Almost immediately, all hell broke loose, with a petition circulated among residents demanding the event be cancelled for various reasons, including that it would attract hooligans, access to the church would be restricted, and the local cricket team would be unable to use their oval on the weekend.

Despite the committee’s recommendation, which was endorsed by the council on October 10, final permission was not forthcoming because, council stated, the promoters had not lodged an official Development Application. The DA was quickly sorted out to the council’s satisfaction and, seven weeks out from the Australia Day weekend, the Lord Mayor announced the event would go ahead. But while Forcefield busied itself with the job of getting the event organised, forces were gathering against it.

The first bombshell came when the SCLC placed a ban on the TT, saying the promoters had failed “to ensure that maximum regional employment would be created”, intended to engage ‘volunteer’ labour outside the award, and had failed to provide “adequate guarantees for the protection and safety of those engaged in providing labour for the event”.

Next, local police chief Inspector Bob Burridge, who had been supportive from the start, was replaced by Sgt Bob Morgan, who drew up a whole new set of requirements regarding public safety and security. On 15 January, just 12 days before the race, the police issued a statement formally refusing the event application, citing “safety issues”. It was the last straw for Forcefield, who had engaged experienced event manager Bob Barnard to work through the various engineering and logistical issues.

Within hours of the announcement of the cancellation of the TT, the local media was wringing its hands that the area had lost a golden opportunity. “A powerful message has been sent to the rest of Australia; Don’t bother doing business in Wollongong. You’ll get burnt – badly burnt”, headlined the Illawarra Mercury. On 21 January, more than 1000 people attended a rally at the ‘circuit’ site to express their anger and disappointment. Local business owners spoke of the substantial losses they would incur, while Bob Barnard addressed the crowd. The rally concluded after a symbolic ride around the circuit by hundreds of bikes, closely monitored by radar-equipped police vehicles. And with that, the Port Kembla TT passed into history – or did it?

Back in Sydney, Forcefield chairman Phillip Harris was seething. His company had lost a considerable amount of money, but more importantly to him, it had lost face. Forcefield had a long history of successful sporting promotion, including Mr Motocross, the Pepsi Pro Junior surfing contest and the Bathurst 12 Hour car race, and he simply could not accept this slap in the face.

Well connected with senior officials of the NSW Labor Party, Harris set about reinstating the TT at Easter, just three months away. Negotiations with police resumed, resident meetings organised, unions consulted and money spent at an alarming rate.

In accordance with police demands, virtually the entire circuit was to be enclosed in plastic water barriers, requiring some to be brought from as far afield as Perth. Every available section of Airfence was hired, including some from Malaysia. Temporary cyclone fencing to contain spectators within stipulated areas was brought in, and extra security engaged to keep people out of prohibited areas. It was a colossal amount of work to be achieved in a very short time.

Ironically, the biggest hurdle was the lack of entries. Back in January, the off-season date suited many, but with the Australian Superbike Championship in full swing by Easter, the major teams refused to enter as it wasn’t on their schedule or within their budgets.

Despite all the drama, including yet another eleventh-hour list of extra requirements from the police, the TT went ahead.

The pit area was set up on the seafront in the grounds of MM Kembla, a local transport company, with the starting grid opposite. This was half a lap away from the finish line, which was located on the other side of the circuit, opposite the main spectator area in the park. Spectators were prevented from seeing the start, but at least they could see the finish.

From the starting grid opposite the pits, it was a 100-metre dash to Turn 1, a 90-degree left onto a newly laid stretch of tarmac (put in place to eliminate disused railway tracks), through a sweeping left and on towards the right-hand Broady’s Bend. Then it was onto the anchors for a double-left past the Court House and Police station and onto Military Road. This was a mixture of tar and concrete, running steeply uphill to a tight chicane that was placed on the crest of the hill. Out of the chicane and down the other side brought riders over the finish line and to another right-angle left into Gloucester Boulevard, with a sharp climb leading to a fast left over a rise and onto the seafront. From there it was a flat-out blast, slightly downhill through another sweeping right to the starting area.

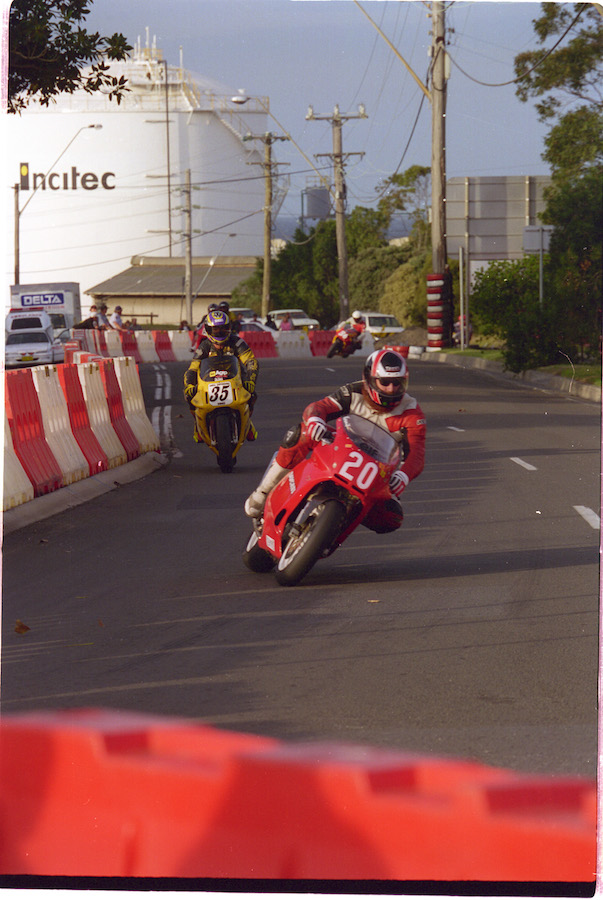

There were anxious faces as the first practice session got underway, albeit 90 minutes late after police demanded yet more Airfence and water barrier, but it was completed without incident. Among the entries were Kiwi road circuit specialists Tony Rees and Dave Cole, who both praised the layout.

Perhaps fittingly, it was local star Trevor Jordan on an ex-Team Kawasaki Superbike who snatched pole with a lap of 1m29.83s – an average of 164.3km/h – fairly scorching for a lap that included three first-gear corners and a chicane. Not everyone made it through qualifying unscathed, though. Talented South Australian (and lately AMCN road test editor) Paul Young on a Kawasaki ZX-6R had Rob Carter’s Yamaha TZ250 seize in front of him at the flat right in front of the pits, the ensuing crash sending Young to hospital with back injuries.

In the opening race, the combined Formula 1/BEARS Sprint, John Manwarring crashed his YZF750 Yamaha just before the Court House, sustaining multiple breaks to his legs and other injuries. With wreckage strewn across the track, the race was red-flagged and awarded to runaway leader Jordan. It was a dramatic conclusion to the opening day, and while the spectators partied on into Saturday night, officials and volunteers laboured hard to get the place ready for the big day.

Sunday dawned bright and sunny. Before long there was a vast queue of people lined up at the gates, while the houses along the straight on the inside of the circuit had festivities going full bore, with homespun rock bands playing in front yards and everyone having a fine old time.

The program resumed with the round one of the Formula Two TT, won by Martin Atlee on his Honda RS250 from Tony Lees’ Ducati. Atlee, whose father Len was a multiple Australian TT winner, found his two-stroke twin difficult to get off the line and in round two was near last as the field stormed away. A stirring ride through the field got him as far as second, which turned into a win when local truck driver Ian Hambridge’s CBR600 Honda dropped a plug lead.

The main two-leg Formula One TT (with the BEARS class running concurrently) looked like being a benefit for Trevor Jordan – until two laps into the 6-lap opening leg. At the same spot where Manwarring had crashed the day before, Jordan’s Kawasaki snapped a conrod in front of the packed field and shrouded the circuit in a thick cloud of blue smoke. Those behind were blinded, Rob Carrall and Glen Evans crashing in the ensuing melee. This left Phil Harper and Ian Hambridge battling for the lead until Harper’s gear lever fell off, promoting Wayne Clarke to second.

Jordan was a non-starter in the 10-lap second leg, but Clarke, Hambridge, Cole and Lees put on a great show until the race was cut by two laps because of gale-force winds and the onset of rain. Cole snatched the race from Hambridge on the final bend, but overall victory went to 30-year-old Hambridge. Phil Allen took the BEARS section in a Ducati 1-2-3.

Support events included a combined 250cc Production/Single Cylinder race that featured some sensationally close dicing, the win going to local Chris Wilkie (Suzuki RGV250) while Phil Dombkins (Honda CR500) was the Singles winner.

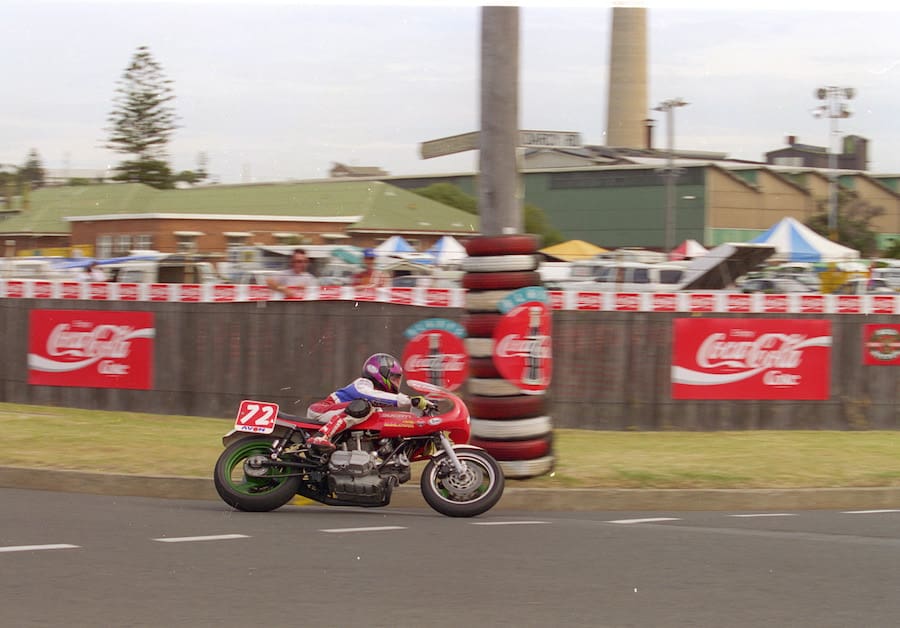

Historic classes, running under the banner of Forgotten Eras, filled out the program with races split into Unlimited, Under 500cc and Under 350cc.

Darkness was falling by the time Hambridge received his impressive Illawarra Mercury Trophy from radio personality and bike enthusiast Doug Mulray. The crowd of 11,500 was the biggest to attend a national event (as opposed to a Grand Prix or World Superbike) for many years, vindicating the promoter’s stance that this type of racing had a wide appeal.

Newspaper reports congratulated the promoter on toughing it out and expressed hopes that the TT would become an annual event, but the exercise had proved to be a financial disaster for Forcefield, to the extent that the company never promoted again.

The Port Kembla event marked the final closed-roads race in NSW (apart from Mount Panorama in 2000) and the final time the Australian TT, a title stretching back 82 years, would be contested. It really was the End of the Roads.