Today we look with envy upon the privileged few who are let loose to ride as fast as humanly possible on ordinary public roads that otherwise would be carrying SUV-loads of schoolchildren, trucks, occasional tractors and of course motorcycles. There aren’t many of these venues left, except in enlightened places like New Zealand, Ireland, Belgium, Holland and, oh yes, the Isle of Man.

It wasn’t always like this. In fact, Australia’s first purpose-built racetrack (as opposed to speedway ovals and reclaimed airfields) wasn’t opened until 1 January 1953, at a waterless saltbush paddock at Port Wakefield north of Adelaide. Prior to this, road racing was conducted – surprise, surprise – on roads. These were ordinary roads, specially closed to normal traffic so that cars and motorcycles could scream around with the full cooperation of local authorities, including the police. These events were seen as a sound idea to bolster the coffers of local businesses as they brought in people that would otherwise not venture to such parts – tourists. The name Tourist Trophy, however, came about because of the touring nature of the motorcycles. The French term grand prix (translation great prize), was equally in vogue, so Australia adopted both.

The first Australian TT was held in the Goulburn district in April 1914, the plan being to rotate it between the states thereafter, something that failed to happen for many years. The 1914 TT took place on a 33-mile (53km) course linking the towns of Breadalbane and Collector, and took nearly three hours to complete. Later the same year, the first Australian Grand Prix was conducted near Bathurst, and was without doubt the biggest motorcycle event ever held in NSW up until that time. After nine laps of the 15.5-mile (25 km) circuit, the winner was Edgar Meller on a Douglas, a victory that the British brand celebrated widely in its advertising.

Some circuits measured over 50km, and few, if any, were tar sealed until well into the 20th century. Even Phillip Island’s original road course, the venue of many Australian TTs and GPs, remained a gravel track for its entire existence up to WWII, and Mount Panorama was similarly not tarred until the second year of racing in 1939. In most cases, these events were annual fixtures, each one settling on a traditional date, and more often than not they took place with car races, each discipline supplying its own officials and infrastructure.

Consider the pre-Mount Panorama races held each Easter at what was known as the Vale Circuit, south-east of Bathurst from 1931 to 1937. A goodly proportion of this circuit comprised the main road from Bathurst to Goulburn, which, along with the rest of the 7.23-mile (11.5km) lap, was unsealed and either chokingly dusty or a sea of mud. As the main road could not be closed to through traffic, the solution was to rope off one half of the road, allowing traffic to pass on one side (guided by motorcycle-mounted marshals), with racing taking place on the other. It’s no surprise that in time the rope barrier came to be considered inadequate, so a low earth bank was bulldozed into place to separate the racers from road users.

Phillip Island’s road circuit held its first motorcycle event, the Victorian TT, in 1928 over a 12-mile (19.5km) lap outside Cowes. The course for bikes, known as the Rhyll circuit, differed from that for cars in that it was almost twice as long and incorporated an extra section of what was described as a “three-ply cart track” of deep rutted sand. Fortunately, sanity prevailed and the Rhyll circuit was only used once. Thereafter the bikes and cars used the same 6.5-mile (10.5km) public roads circuit. The bikes settled on the date of the annual Australia Day long weekend in January – the same date today occupied by the AMCN International Island Classic – and ran from 1931 until 1940. The roads that comprised the circuit are still there and are well signposted. Next time you’re on the island, do a lap or two – you’ll come away with a new admiration for the pioneers of our sport.

The situation for promoting the races varied slightly from state to state, but the logistics were similar. South Australia had quite a few public road circuits: Lobethal, Woodside (which included two railway crossings), Port Elliot (Victor Harbor), Marion and several lesser tracks. But a series of serious accidents led to the state government imposing a total ban on road course events in 1953 – a ban that led to the building of the Port Wakefield track, and which was not rescinded until the advent of the Australian Formula 1 Grand Prix in Adelaide in 1985.

Tasmania had Longford, another extremely high-speed circuit, which also saw numerous fatal accidents and fell into disuse when nearby Symmons Plains began operating. Queensland ran events at Southport and once at a soon-to-be housing estate at Surfers Paradise. Western Australia continued longer than most with road courses at Bunbury, Geraldton, Collie, Kalgoorlie and Donnybrook in what was known as ‘round the houses’, but eventually the safety lobby shouted down the enthusiastic local business owners and the annual events ceased. Perhaps the big daddy of all was the sensationally quick circuit at Mildura, which was the fastest venue in the country during its existence from 1954 to 1957. There were also Victorian road courses at Ballarat, Darley and Little River, but by the mid-60s these too were gone.

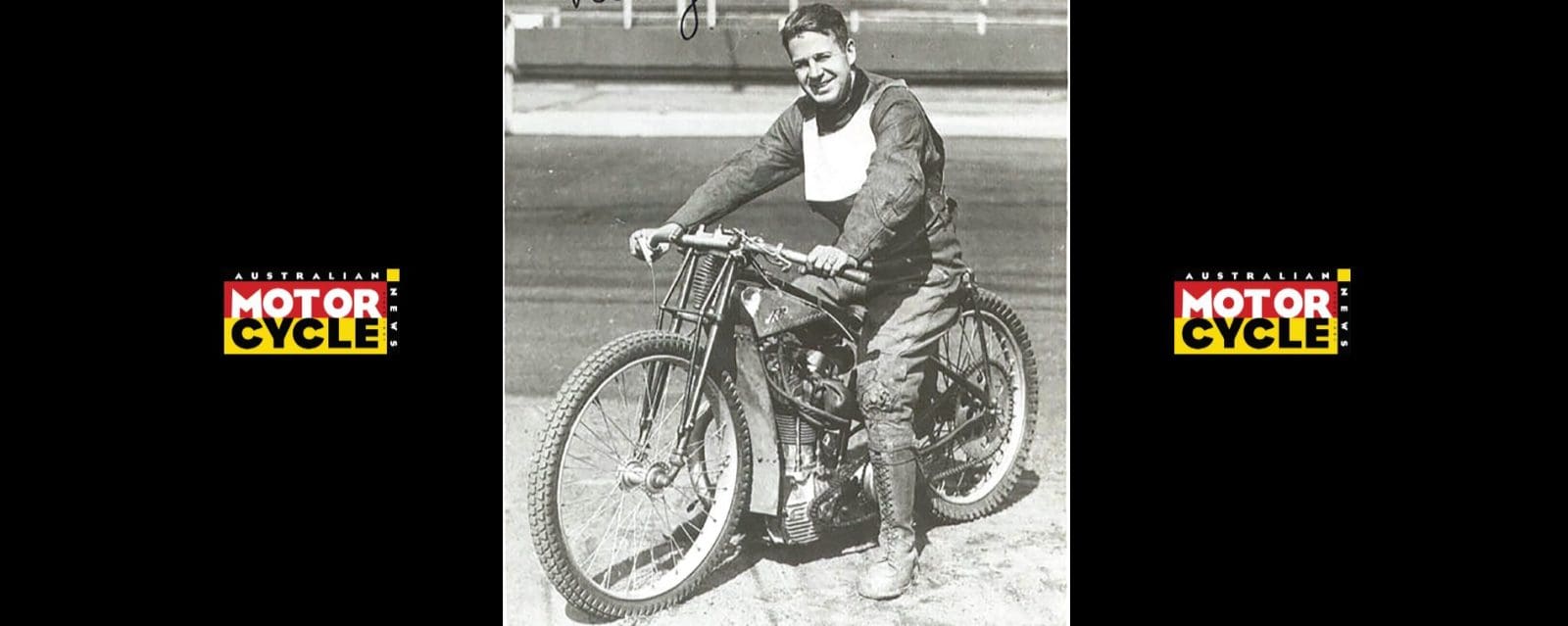

Right: Jimmy Pringle corners his Norton at the Vale Circuit in Bathurst in 1935

In New South Wales, the attitude was less accommodating, the state police being vociferous opponents to such folly. Short-lived courses existed at Gnoo Blas (Orange), Hartley Vale (Lithgow) and Parramatta Park (a network of scenic roads within the park). Only Mount Panorama has stood the test of time, and today it is a concrete-lined road course for four-wheel racing that is more racetrack than public thoroughfare. However, in the immediate post-war years, Mount Panorama’s biannual events (at Easter and the NSW October long weekend) were battlegrounds between the NSW Police department, the local government and the promoters. Matters came to a head in 1947 when the Easter races were cancelled after the Police Commissioner refused to sanction the event. An appeal to the Court of Petty Sessions was successful, but too late to save the meeting, which was rescheduled for October. Seething with the defeat, the Police Commissioner announced that all competitors (bikes and cars) at the October event would be liable to be charged for dangerous driving under the Motor Traffic Act. Only the intervention of senior government members was able to rein in the police and saved the circuit from extinction.

By the 70s, it looked all over for the road circuits, and with a plethora of new if relatively short tracks springing up, there was little enthusiasm to continue the hard work of promoting closed-road circuits in any case. Phillip Island opened in 1957, easing the paucity of venues in Victoria, and Lakeside, Calder, Symmons Plains, Oran Park, Catalina Park (Katoomba), Mallala and soon after, Amaroo Park in 1969, all opened for business and did very well.

But there was, it seemed, one more card to play in the road-racing pack. As a territory and not a state, the ACT made up its own mind on certain things, and one thing was the question of building a motorsport venue. Numerous plans had been drafted, some coming tantalisingly close to fruition before the usual red tape and brinkmanship stifled enthusiasm and wherewithal, and the proposal collapsed. As a result, Canberra-based racers were forced to travel incessantly to compete in open meetings either in Sydney or further afield. To get rides in restricted race meetings, many had to resign from their own Canberra club and join another club in Sydney.

Then, out of the blue, the small Canberra Road Racing Club was approached by a private individual to ascertain interest in using a network of streets to form a racing track at a site in Tuggeranong. The streets, complete with kerbs, gutters and drainage, had been put in place in readiness for the new suburb of Macarthur – one of several such projects where the infrastructure had gone in but the planned housing had, as yet, failed to proceed. Amazingly, the Department of the Capital Territory, which was responsible for the administration of government in the ACT at the time, had already been approached and were quite enthusiastic about the idea. The next step was approaching the police, and again, the response was basically 100 per cent positive.

Had the proposed venue been a few kilometres courses at Bunbury, Geraldton, Collie, Kalgoorlie and Donnybrook in what was known as ‘round the houses’, but eventually the safety lobby shouted down the enthusiastic local business owners and the annual events ceased. Perhaps the big daddy of all was the sensationally quick circuit at Mildura, which was the fastest venue in the country during its existence from 1954 to 1957. There were also Victorian road courses at Ballarat, Darley and Little River, but by the mid-60s these too were gone.

In New South Wales, the attitude was less accommodating, the state police being vociferous opponents to such folly. Short-lived courses existed at Gnoo Blas (Orange), Hartley Vale (Lithgow) and Parramatta Park (a network of scenic roads within the park). Only Mount Panorama has stood the test of time, and today it is a concrete-lined road course for four-wheel racing that is more racetrack than public thoroughfare. However, in the immediate post-war years, Mount Panorama’s biannual events (at Easter and the NSW October long weekend) were battlegrounds between the NSW Police department, the local government and the promoters. Matters came to a head in 1947 when the Easter races were cancelled after the Police Commissioner refused to sanction the event. An appeal to the Court of Petty Sessions was successful, but too late to save the meeting, which was rescheduled for October. Seething with the defeat, the Police Commissioner announced that all competitors (bikes and cars) at the October event would be liable to be charged for dangerous driving under the Motor Traffic Act. Only the intervention of senior government members was able to rein in the police and saved the circuit from extinction.

By the 70s, it looked all over for the road circuits, and with a plethora of new if relatively short tracks springing up, there was little enthusiasm to continue the hard work of promoting closed-road circuits in any case. Phillip Island opened in 1957, easing the paucity of venues in Victoria, and Lakeside, Calder, Symmons Plains, Oran Park, Catalina Park (Katoomba), Mallala and soon after, Amaroo Park in 1969, all opened for business and did very well.

But there was, it seemed, one more card to play in the road-racing pack. As a territory and not a state, the ACT made up its own mind on certain things, and one thing was the question of building a motorsport venue. Numerous plans had been drafted, some coming tantalisingly close to fruition before the usual red tape and brinkmanship stifled enthusiasm and wherewithal, and the proposal collapsed. As a result, Canberra-based racers were forced to travel incessantly to compete in open meetings either in Sydney or further afield. To get rides in restricted race meetings, many had to resign from their own Canberra club and join another club in Sydney.

Then, out of the blue, the small Canberra Road Racing Club was approached by a private individual to ascertain interest in using a network of streets to form a racing track at a site in Tuggeranong. The streets, complete with kerbs, gutters and drainage, had been put in place in readiness for the new suburb of Macarthur – one of several such projects where the infrastructure had gone in but the planned housing had, as yet, failed to proceed. Amazingly, the Department of the Capital Territory, which was responsible for the administration of government in the ACT at the time, had already been approached and were quite enthusiastic about the idea. The next step was approaching the police, and again, the response was basically 100 per cent positive.

Had the proposed venue been a few kilometres up the road across the border, it would have been subject to the dreaded NSW Speedways Act, which had almost wiped out motorsport in NSW when it came into force in 1959. However, being the ACT such things as permanent safety fences were not required, and hay bales (deemed fire hazards in the NSW Speedways Act) could be put in place where required. As the various loose ends were tied up, members of the small but dedicated CRRC began to look towards a date for their meeting. Resisting the urge to create a long, high-speed circuit, the club settled on a 2.8km lap, which had some interesting changes of elevation and provided a natural grandstand of grassed viewing areas. Because there was no way of charging admission, spectators were admitted free but strongly encouraged to purchase a printed race program.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the major impediment to the club’s proposed inaugural Open Road Race meeting came not from Canberra’s bureaucrats but from the notoriously negative Auto Cycle Union of NSW, which was responsible for issuing the race permit and insurance. The ACU refused to issue a permit for an Open meeting until the Canberra club had proven its ability to promote, and agreed only to a permit for a ‘restricted’ event involving no more than five clubs.

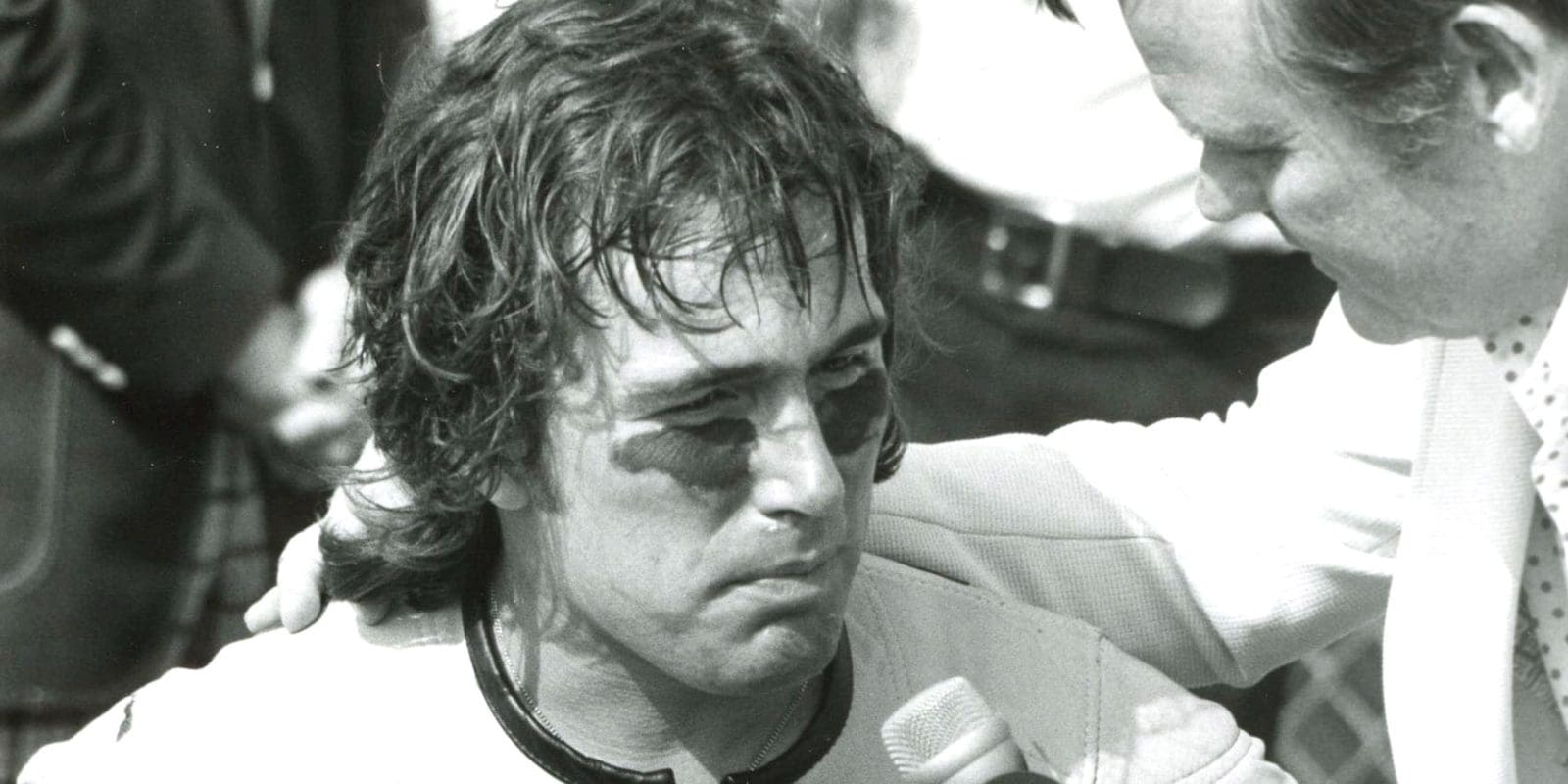

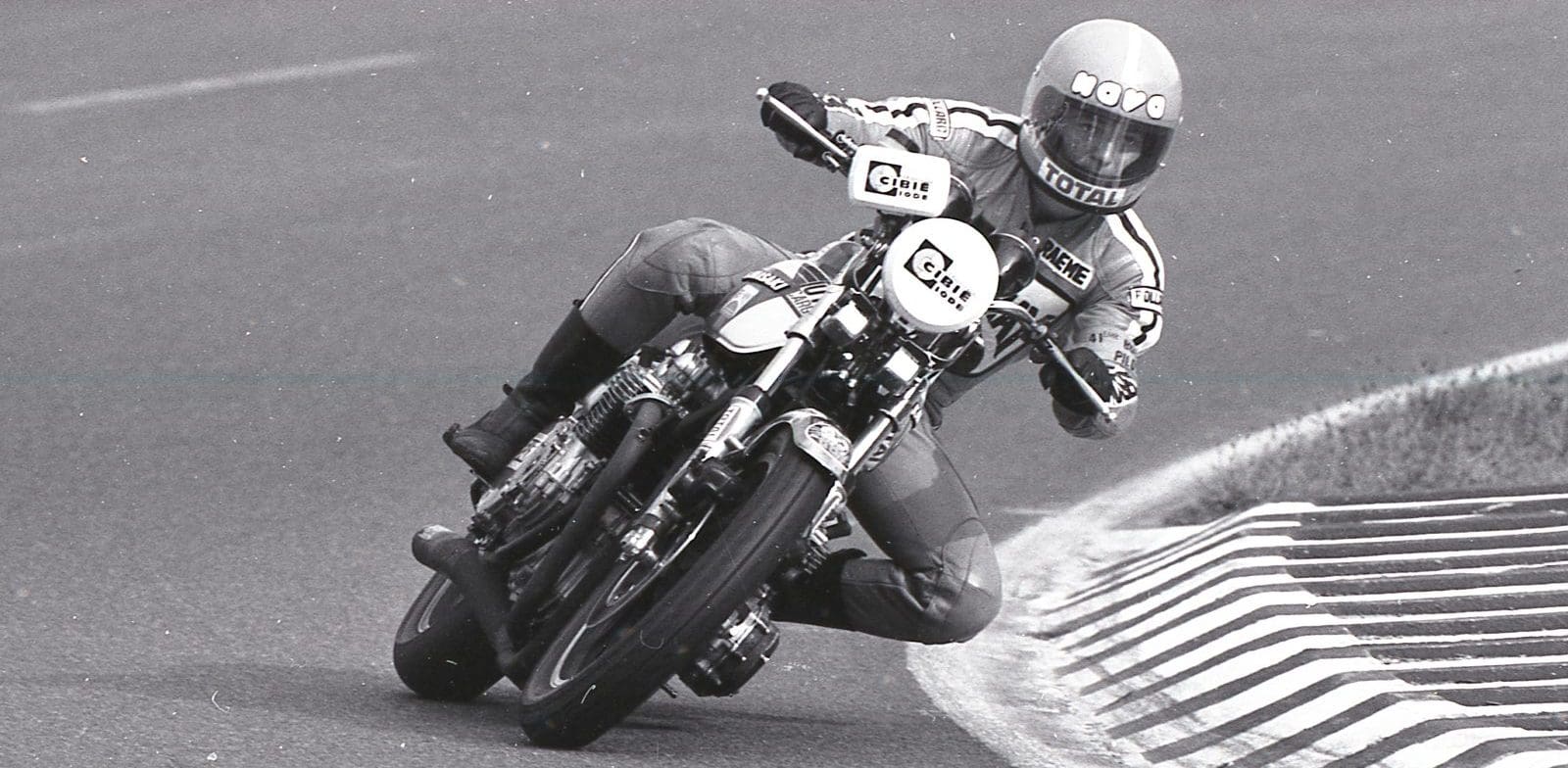

CRRC wisely selected the four invited clubs from those with the strongest number of road racers, so that the meeting that took place on the weekend of 7-8 October 1978 was an Open meeting in all but name with a total of 107 entries including leading A-graders Ron Boulden, Murray Sayle, John Pace, Graeme McGregor, Robbie Phillis, Roger Heyes, Graeme Crosby, Stu Avant, Peter Walker, Lee Roebuck and Roy Denison.

The organisers were delighted to see more than 3000 spectators turn up for official practice, which was held on Saturday afternoon. The following day the hills were crammed with more than 10,000. Refreshment stalls, manned by club members, sold out of their wares, and everyone went home thrilled with what turned out to be a sensational day’s racing, with the main 10-lap event won by Stu Avant on the Team Hunter Suzuki RG500. There had been a few minor accidents, the most serious leaving Robbie Phillis and Tony Sims with broken collarbones.

Still, the ACU remained unmoved and refused an Open permit for the next planned meeting at what had become known as Macarthur Park, named after the future suburb. Eventually the recalcitrant body agreed to what it termed a ‘Special State Restricted’ meeting in November 1979, which allowed all NSW licence holders to enter, including future world champion Wayne Gardner. Hungry for more action after the success of the 1978 meeting, 12,000 spectators were asked to part with $2 each to enter.

Despite being concerned about such things as concrete gutters (fortunately of the spoon type and not square-edged), Gardner led home local star Murray Ogilvie and veteran Len Atlee in the Unlimited A-grade race. The feature race was stopped after only two laps when a mob of kangaroos wandered onto the track, and were chased away by trail bike riders. The meeting was deemed an even bigger success than the first, and finally the ACU allowed the club an Open permit for the third event held in March 1981 as part of the annual Festival of Canberra. Star of the meeting was hard-riding Dennis Neill on the Team Honda CB1100R Superbike.

It appeared that the efforts of the CRRC had not gone unnoticed by the Federal Government, which announced an $8 million grant to create a permanent circuit within the ACT as part of its 1980 election promises. It looked like the territory’s racers would finally get a home circuit, though it would mean the end of Macarthur Park, upon which houses were finally set to be built in early 1982. But the new track never came to pass, along with a number of other supposedly iron-clad pre-election promises from the Liberal government, and the CRRC was back where it started – trackless. Morale plummeted, but the club decided to hold a ‘Farewell to Macarthur Park’ on 1 November 1981.

For the first and only time, sidecars raced at the track with a bumper 18-strong field including Geoff Taylor, Stan Bayliss, Bob Martin, Vince Genova, Gavin Porteous and Doug Chivas. With the knowledge that this would probably be the last chance to race on a public roads circuit, more than 200 solo entries poured in as well. Unlike the previous three meetings, the finale was something of a prang-fest with Andrew Johnson, John Wood and Steve Trinder all crashing. Robbie Phillis was the star of the meeting, winning the Feature and A-grade races and establishing the track’s all-time lap record of 1m 20.8s.

Just three months later, the houses began to go up, and the ACT’s racetrack was gone, along with its hopes of ever getting the permanent venue it had been promised.

Next month: The 1996 Australian TT at Port Kembla – the final fling.

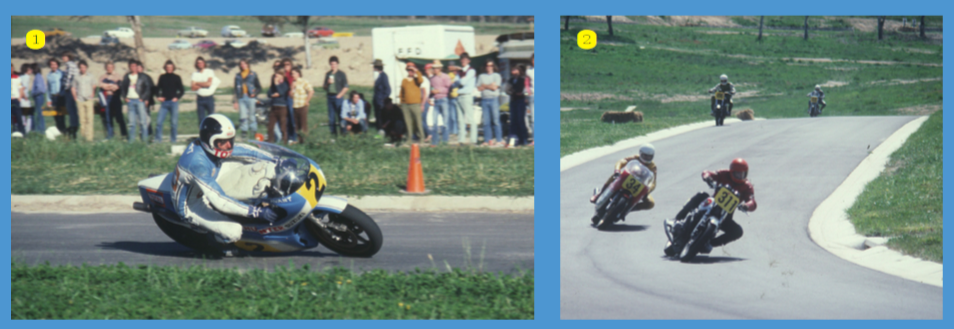

2. Again at the opening Macarthur Park meeting, Roy Denison (Kawasaki) leads Jim Scaysbrook (NCR Ducati)

WORDS PETER TURNER PHOTOGRAPHY PETER SHANNON & KEITH WARD